Carlos Lehder: The Nazi Drug Lord

by Zoltanous

Carlos Lehder, born September 7, 1949, in Armenia, Colombia, emerged as a pivotal figure in the Medellín Cartel, one of history’s most infamous drug trafficking organizations. The son of Wilhelm Lehder, a German engineer who immigrated to Colombia before World War II, and a Colombian mother, Lehder inherited a dual cultural identity that shaped his eclectic ideology. His father, originally named Kurt Wilhelm Rudolf Lehder, naturalized as Guillermo in Colombia and built the iconic La Posada Alemana guesthouse in Armenia, which hosted dignitaries like former President Alberto Lleras Camargo. Lehder was the third of four siblings; his parents divorced when he was 15, prompting his move to New York with his mother, who came from a family of jewelers in Manizales. He blended influences from Nazism, Catholicism, environmentalism, anti-communism, anti-imperialism, and Bolivarianism, aspiring to establish a National Socialist regime in Colombia while promoting Hispanic-American unity.

Lehder’s early life foreshadowed his criminal trajectory. At 15, he moved to New York, engaging in petty crimes like car theft in New York and Michigan, even smuggling stolen vehicles back to Colombia. This included smuggling stolen cars to Medellín via a brother’s dealership and small-scale marijuana trafficking between the U.S. and Canada after training as a pilot. Locally, he earned nicknames like Hombre del mundo (Man of the World) or El Loco and Rambo for his bohemian lifestyle as a fan of the Beatles and Rolling Stones, complete with lavish cars, amid Quindío’s coffee boom. He dropped out of school to study the works of Niccolò Machiavelli, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, Hermann Hesse, and Adolf Hitler — whose Mein Kampf profoundly influenced him. By his late teens, he faced multiple arrests for theft and smuggling. In 1973, at age 24, he received a two-year sentence for smuggling 300 pounds of marijuana in a fake airplane engine. While imprisoned in Danbury, Connecticut, Lehder met George Jung, a seasoned drug trafficker who introduced him to U.S. contacts. After their release in 1975, they partnered to transport cocaine from the Bahamas to the U.S. using small planes, a venture that laid the groundwork for Lehder’s rise in the drug trade. Lehder pioneered this “air fleet” model, initially smuggling marijuana before shifting to cocaine, revolutionizing the trade.

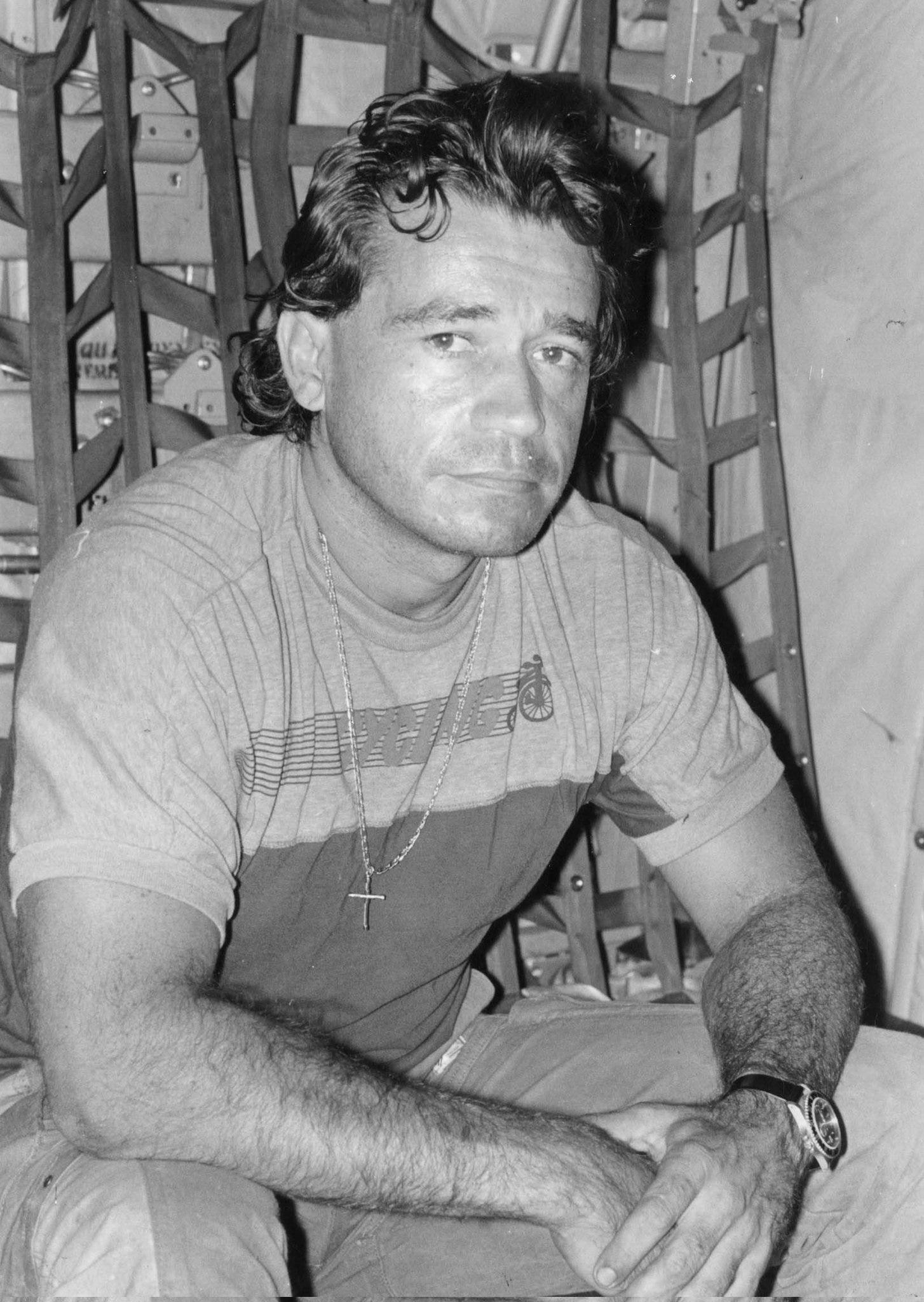

A photo of Lehder

This operation, bolstered by bribing Bahamian officials — including monthly payments of $150,000 to Everette Bannister, an aide to Prime Minister Lynden Pindling, for protection and sourcing cocaine from Pablo Escobar, marked the genesis of the Medellín Cartel. Lehder’s innovative smuggling tactics — centralizing operations on Norman’s Cay in the Bahamas, where he acquired 75% of the island through a hotel purchase and used violence and intimidation to evict residents, earned him the moniker “the Henry Ford of cocaine.” On the island, he hoisted the Colombian flag, sang the national anthem daily, installed radar systems and doberman guard dogs, and processed up to 3,000 kg of cocaine per hour at peak operations. The John Lennon statue was particularly controversial: a 9-foot depiction, naked with a German helmet, a bullet-holed guitar, and “PAZ” inscribed on the genitals and one hand; it was stolen in 2003 and is now in storage. Alongside Escobar and other associates dubbed Los Mágicos (The Magicians) for their rapid wealth accumulation, Lehder transformed the cartel into a multi-billion-dollar enterprise.

Yet, for Lehder, cocaine was more than profit — it was a weapon. He viewed drug trafficking as an anti-imperialist struggle to destabilize the United States, which he despised as the epitome of global capitalism. Lehder argued that “Cocaine is the Colombians’ atomic bomb against the US.” His anti-American fervor coexisted with admiration for John Lennon’s Vietnam War stance — evidenced by the statue on Norman’s Cay—and ties to Colombia’s National Socialist Movement. He survived a 1981 kidnapping by the M-19 guerrillas, during which he was shot but escaped, further fueling his paranoid worldview. During the ordeal, he escaped wounded and offered a substantial reward to an unknown helper, which sparked the formation of the MAS (Muerte a Secuestradores) anti-kidnapping paramilitary group. This prompted heightened security, including ex-intelligence agents and a weaponized limousine (previously owned by a former German chancellor) that survived a bombing attempt by the rival Cali Cartel.

His properties reflected his extravagance: La Posada Alemana featured a bike track, Swiss-style cabins, a winery, and animal cages, while Hacienda Pisamal was notorious for hosting orgies, prostitutes, and even homosexual encounters with employees. Lehder’s philanthropy included donating a plane to Quindío’s government (later sold but possibly repurchased secretly) and a fire truck to the town of Salento, though these acts were often viewed with suspicion amid “hot money” scandals in Colombian politics and sports.

The Medellín Cartel

Lehder emphasized that the so-called cartel was not a monolithic entity but rather 26 competing “export offices” in Medellín, with his being one of the largest. His relationship with Escobar was strictly business, they never socialized families and it soured due to Lehder’s cocaine-fueled paranoia and megalomania. His fortune reportedly peaked at nearly $100 million (though some estimates suggest $8-9 billion including broader operations), offset by expenses like bribes and security, much lost during clandestine periods in Cuba (where he reunited with fugitive Robert Vesco), Mexico, Peru, Brazil, Nicaragua, and Colombian jungles alongside guerrillas. The rift with Escobar deepened in 1986 when Lehder, under the influence of marijuana and cocaine, killed one of Escobar’s hitmen at Hacienda Nápoles over a romantic dispute involving a woman. Lehder, who has three children, once offered twice to pay off Colombia’s national debt (around $13 billion in the 1980s) in exchange for amnesty and an end to extraditions, showcasing his delusions.

Lehder’s political ambitions crystallized in 1982 when he founded the National Latin Civic Movement (also known as Movimiento Nacional Latino) in Quindío, Colombia. This party fused anti-communism, anti-imperialism, anti-Zionism, non-alignment, and paradoxically — anti-fascism, though scholars like A. James Gregor argue this was a veneer for his own fascist leanings. The party, held at La Posada Alemana, gained over 10,000 followers and secured three congressional seats in 1984, amid Lehder’s ambitions for Quindío’s governorship. German sources explicitly label him “Nazi-affine,” viewing his drug smuggling as a deliberate tool to destroy decadent American society. Lehder identified as a Latin Americanist, nationalist, Bolivarian, ecologist, and Catholic, advocating for drug legalization and a NATO-like Hispanic-American alliance with its own military. He publicly denounced Colombia’s extradition treaty with the U.S., defended Hitler by denying the Holocaust, and funded nationalist paramilitary groups to advance his anti-American agenda. His boldness peaked with taunts against the DEA, including leaflets in the Bahamas proclaiming, “Go home, DEA.”

Lehder was implicated in broader violence, including the 1984 assassination of Justice Minister Rodrigo Lara Bonilla and a 1986 shooting attack on ambassador Enrique Parejo González in Budapest. Rumors also persist of ties to the CIA’s Iran-Contra scandal and other international intrigues. Despite recent denials in 2025 interviews where he claims to have “absolutely nothing to do with the Nazis” and attributes past behaviors to heavy cocaine use while criticizing portrayals like in Netflix’s Narcos for fabricating swastika scenes, the historical evidence of his Hitler admiration and neo-Nazi elements in his party remains compelling. Beyond Narcos, he has been portrayed in films like Blow (as the character Diego Delgado), documentaries such as a 2013 Gangster episode, and interviews including a 1988 El País profile dubbing him the “emperor of cocaine.”

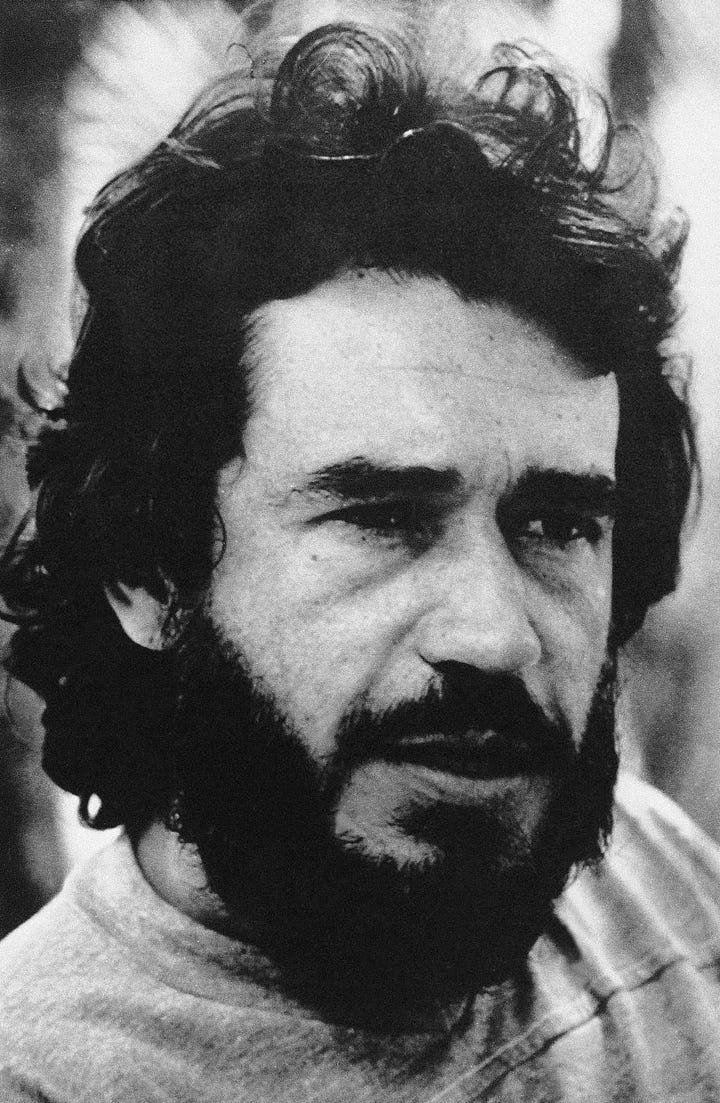

A photo of the National Latin Civic Movement

Lehder’s hubris invited retaliation. A 1980 DEA raid on Norman’s Cay forced him to flee to Colombia, straining his relationship with Escobar. Tensions escalated in 1986 when Lehder killed one of Escobar’s hitmen at Hacienda Nápoles, reportedly prompting Escobar to betray him by tipping off authorities. On February 4, 1987, Colombian police captured Lehder in a raid uncovering cash, Nazi memorabilia, and incriminating photos. The raid occurred at Finca Berracal during a party involving young escorts (aged 16-21) and drugs; tips came from employees, neighbors, partners (possibly Escobar), or even a prostitute. Extradited to the U.S. that day — the first under the 1979 Colombia-U.S. treaty — he faced charges of drug trafficking, racketeering, and conspiracy in a trial in Jacksonville, Florida, receiving a life sentence plus 135 years without parole in 1988.

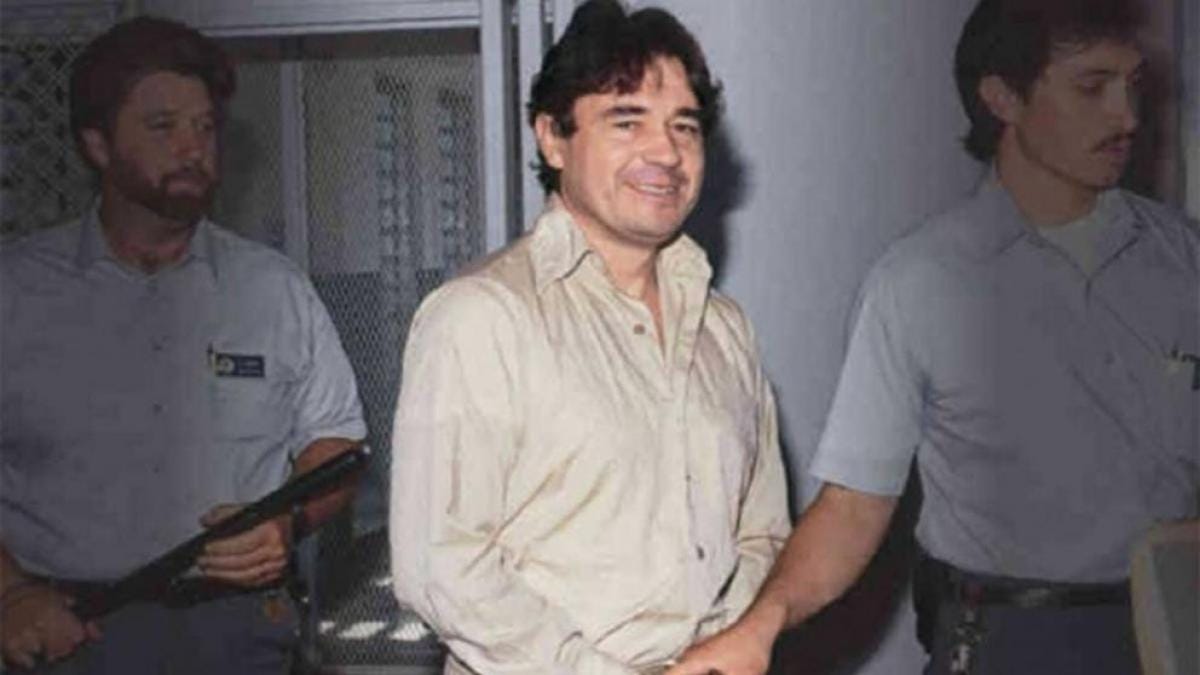

Lehder being extradited

In 1991, Lehder testified against Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega, revealing Noriega’s cartel ties — though he never met Noriega directly, as Escobar handled Panama dealings — and securing a sentence reduction to 55 years. Colombia’s Supreme Court later deemed the extradition illegal. During imprisonment in Marion, Illinois, he faced further legal battles, including a 1995 letter interpreted as a threat, a rejected 2005 appeal, demands from his daughter Mónica to President Uribe in 2009-2012, a denied 2016 clemency request to Obama, and a 2007 bid by Colombia’s Supreme Court to invalidate the extradition citing a 30-year maximum under treaties. After 33 years in U.S. custody, including time in solitary confinement, which he describes as psychological torture — and battling prostate cancer, he was released on June 16, 2020, and deported to Germany, leveraging his father’s citizenship. His release was framed as deportation due to German citizenship rather than purely humanitarian grounds, with ongoing demands from victims (like Lara Bonilla’s son) for new investigations into his crimes. A sunken smuggling plane from his operations remains off Norman’s Cay since 1980. He lived quietly in Berlin for five years before returning to Colombia in March 2025 to visit relatives. Upon arrival at Bogota airport, he was briefly arrested on old arms and narcotics charges but released days later after a judge ruled his Colombian sentence had expired.

In August 2025, Lehder gave a rare English interview to former U.S. mobster Michael Franzese, titled Carlos Lehder: Partner to Pablo Escobar and The King of Smugglers, promoting his 2024 autobiography Vida y muerte del Cartel de Medellín (Life and Death of The Medellín Cartel), written in Spanish over a year in Germany and recently translated to English by Nicolás Patino for Amazon Publishing. In it and the interview, he reflected on his story as one of “crime and punishment,” driven by adrenaline and competition but marked by regrets over choosing the wrong profession and not retiring despite family advice. He emphasized survival without guilt for self-defense, likened his amnesty to that of pirate Woodes Rogers who became Bahamas governor, and issued warnings against the drug trade: “One cannot outfox the foxer,” noting that modern technology makes survival impossible. Now 76, Lehder remains the last surviving major figure of the Medellín Cartel, outliving Escobar and Jhon Jairo Velásquez “Popeye,” his drug lord Nazi-tinged legacy enduring despite his repentant tone and peaceful life in Colombia, where he enjoys simple freedoms like a king-size bed and supermarkets.

Carlos Lehder: Partner to Pablo Escobar and The King of Smugglers interview