Introduction

Due to the absurdity of the online realm, a new phenomenon known as "Conservative Communism" (previously referred to as "Patriotic Socialism") has emerged. Initially, this concept appears so ludicrous that it hardly merits acknowledgement. Regrettably, individuals like Infrared (Haz) have amassed a significant following, advocating for a distorted and amalgamated version of Marxism. We are now confronted with the perplexing notion of political backwardness, labeled as conservative communism or, as he terms it, "capital C-communism." A central belief of this peculiar ideology is the preposterous notion that communism is inherently conservative, patriotic, and even aligned with tradition.

Anti-Conservatism In Marxism and Historical Marxian-Socialism

To delve into this discussion, we must first establish the fundamental principles of traditional philosophy and compare them to Marxist philosophy. Traditional philosophy often finds its metaphysical grounding in philosophical idealism or Platonism. When we examine Marx's philosophy at its surface level, we encounter a blend of idealism and materialism, which can be seen as incoherent. However, this is not the appropriate space to delve into that argument. It was Vladimir Lenin who, drawing heavily from the mature Engels rather than the young Marx, effectively separated Marx from his idealistic elements. For instance, in Lenin's 1909 book Materialism and Empirio-criticism, a book that would later become mandatory reading in higher education in the Soviet Union, he reinterprets Marx's idealistic aspects and presents the following viewpoint:

“Materialism, in full agreement with natural science, takes matter as primary and regards consciousness, thought, sensation as secondary, because in its well-defined form sensation is associated only with the higher forms of matter (organic matter), while “in the foundation of the structure of matter” one can only surmise the existence of a faculty akin to sensation.”

“Sensation depends on the brain, nerves, retina, etc., i.e., on matter organized in a definite way. The existence of matter does not depend on sensation. Matter is primary. Sensation, thought, consciousness are the supreme product of matter organized in a particular way. Such are the views of materialism in general, and of Marx and Engels in particular.”

— Vladimir Lenin, Materialism and Empirio-criticism

By deviating from Marx's opening statement in the Theses on Feuerbach, Lenin interprets sensation, thought, and even consciousness as nothing more than "matter organized in a particular way," seemingly claiming to have resolved the enigmatic issue of consciousness. He goes so far as to assert that this perspective aligns with Marx's own views. However, Marx himself argues that his philosophy corrects classical (or "vulgar") materialism, which erroneously perceives sensation solely in terms of the object or contemplation — precisely the way Lenin reduces sensation to organized matter. Lenin builds upon dialectical materialism and extends it into materialist physicalism, reducing everything to mere matter.

According to this view, consciousness is a product of biology, religion is deemed unreal (in light of Darwinian evolutionary theory and Feuerbach), and all aspects of existence are reduced to the realm of materiality. Consequently, we can comprehend the "capital C-communists" or Marxist-Leninists (MLs) as adherents of physicalism. At this juncture, we witness a complete departure from conservative or traditional philosophy. Traditional metaphysics, rooted in idealism often influenced by forms of Platonism, posits that consciousness is distinct from matter and often upholds the existence of an absolute prior consciousness, such as a divine being. Traditionalism outright rejects any form of materialism. This fundamental contradiction between materialism and traditionalist philosophy is irreconcilable, as it asserts that all of creation, including matter, is contingent upon prior consciousness.

Anti-Conservatism Under Stalin and Mao

Expanding upon this observation, we can turn to the Communist manifesto to understand the communist perspective on religions and other forms of idealism. In the Communist manifesto, Marx and Engels express a critical stance towards religions and other manifestations of idealism. They view religion as a product of socio-economic conditions, a form of false consciousness that perpetuates inequality and diverts attention from material struggles.

“All religions so far have been the expression of historical stages of development of individual peoples or groups of peoples. But communism is the stage of historical development which makes all existing religions superfluous and brings about their disappearance.”

— Karl Marx, Communist manifesto

The logical extension of this perspective can be observed in the policies implemented by the Soviet Union. Critics of "Conservative Communism" may argue that Stalin opportunistically revived Christianity during World War II as a means to rally the nation, as he believed that people would not be willing to sacrifice their lives solely for class interests. However, following the war, Christianity once again faced persecution in the USSR. It is worth noting the irony that when Stalin utilized the Orthodox Church, he essentially mirrored Alfred Rosenberg's heretical concept of the National Church in Nazi Germany. Furthermore, there is no substantial evidence to suggest that Stalin ever seriously engaged with or studied traditional Russian or conservative texts. Dr. Erik van Ree, one of his intellectual biographers, thoroughly examined Stalin's extensive personal library and concluded as such in his book The Political Thought of Josef Stalin.

“Most of these thinkers can be put into the broad category of materialists, socialists and “forerunners of Marxism.” Strikingly, the collection of books contained nothing written by Slavophiles, pan-Slavists or other Russian conservatives (other than literary figures and historians). For all his admiration of Ivan the Terrible and Peter the Great, Stalin seems to have been uninterested in the systems of thought that old Russia produced.… The library reflects a serious lack of interest in traditions other than Marxism.”

— Dr. Erik van Ree, The Political Thought of Josef Stalin

The USSR, as the first country to permit on-demand abortions, actively pursued the eradication of all religions right from its inception. To achieve this objective, it officially denounced religious beliefs as superstitious and regressive. The destruction of churches, synagogues, and mosques was carried out, alongside the ridicule, harassment, imprisonment, and execution of religious leaders. The educational system and media were saturated with anti-religious teachings, while the introduction of "state atheism" became a core belief system.

Lenin emphasized the necessity for communist propaganda to exhibit a militant and uncompromising approach towards all forms of idealism and religion. This approach, known as "militant atheism," played a central role in the ideology of the Communist party and was a high-priority policy for Soviet leaders. Criticism of atheism, agnosticism, or the state's anti-religious policies was strictly prohibited until 1936. Even during Stalin's rule, anti-religious sentiments escalated, as evidenced by the accompanying posters.

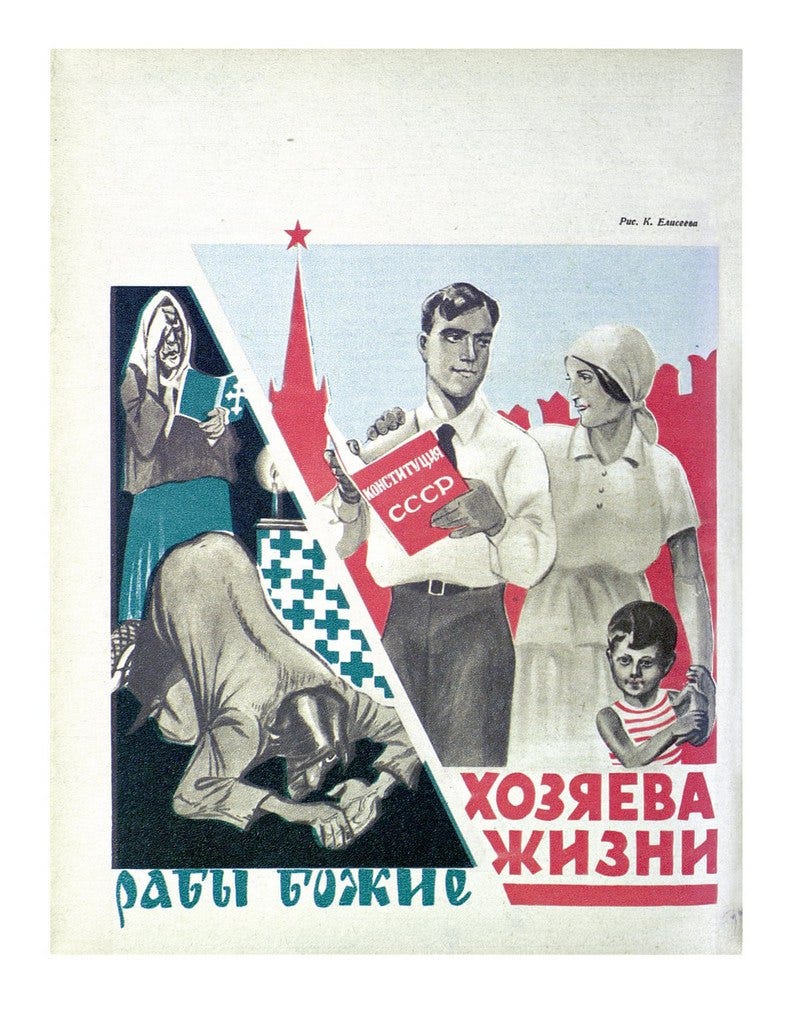

"God’s slaves and Soviet Masters of life". A man holds the Constitution of the USSR in his hands. Poster by Konstantin Yeliseyev, USSR, 1940

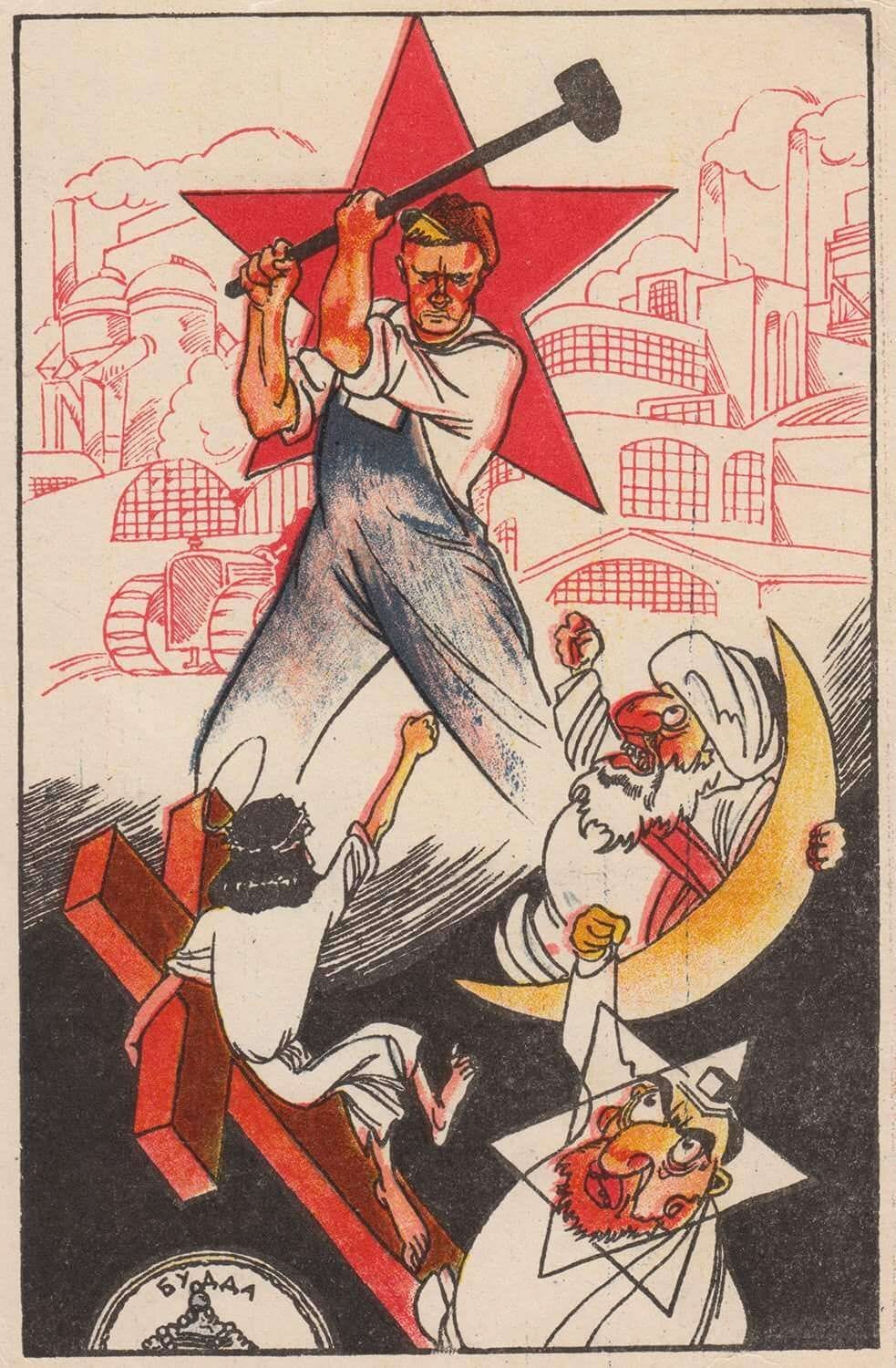

Soviet anti-religion propaganda, more specifically anti-Abrahamic propaganda, dated 1924

Cover of Bezbozhnik in 1929, magazine of the Society of the Godless. The first five-year plan of the Soviet Union is shown crushing the gods of the Abrahamic religions

Before & After. Anti-religion poster depicting the difference between Tsar's Russian Army and Proletariat's Red Army. 1930

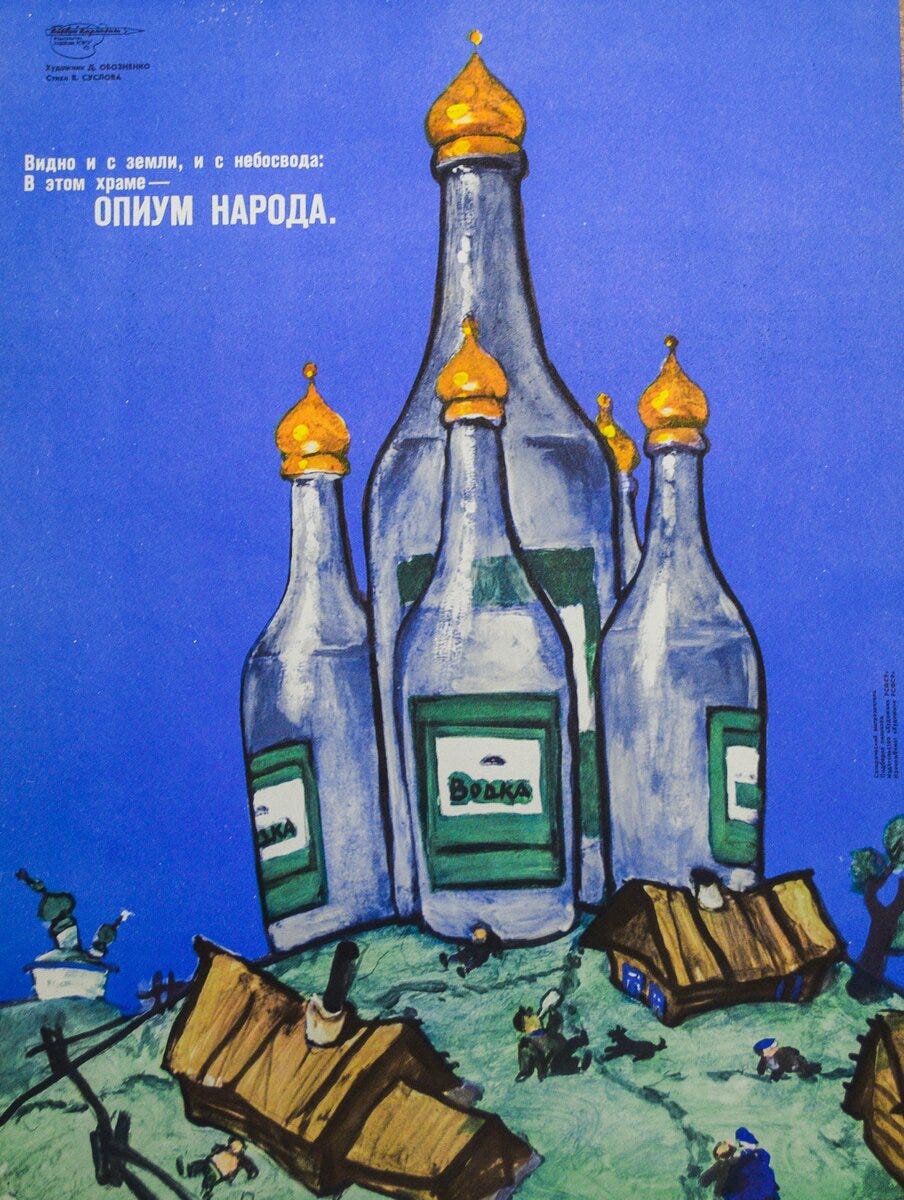

"It can be seen both from the ground and from the skies: there is OPIUM OF THE PEOPLE inside this temple" Soviet anti-religion, anti-alcohol poster, 1980s

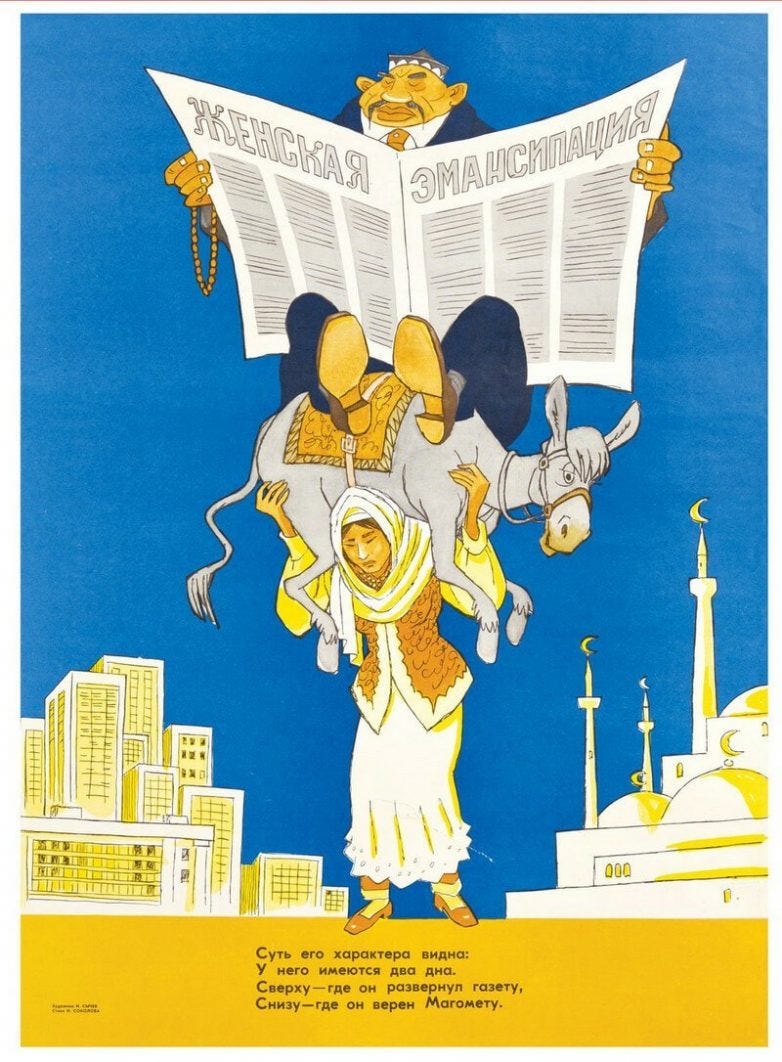

"The essence of his character is clear: it operates on two levels. Up above, he's showing off his paper, down below, he's true to Muhammad." Newspaper title: Women's emancipation. Soviet anti-religion poster, 1977

The state actively sought to exert control over religious organizations and meddle in their internal affairs with the ultimate aim of eradicating them. This included monitoring the activities of religious leaders and bodies. While Lenin did not openly endorse widespread violence against Christians by members of the Red Army, high-ranking Soviet officials like Yemelyan Yaroslavsky took responsibility for these killings. Numerous documented acts of violence included cutting up unarmed prisoners, scalping individuals, torturing believers, shooting priests' wives and even children, and many other atrocities committed by the Red Army.

By 1930, the Soviet Union had witnessed the murder of 31 bishops, 1,600 clergy members, and 7,000 monks. According to available statistics from 1930, 48 bishops, 3,700 clergy members, and 8,000 monks and nuns were confined in prisons under severe conditions of starvation. The "International League against the Third International" in Geneva released statistics on August 6, 1935, indicating that 40,000 priests had been arrested, banished, or killed in Russia. The 1929 Laws on Separation of Church and State also had significant implications. Under these laws, religious ministers could be charged exorbitant rents, ranging from 5 to 10 times more than what workers would be required to pay for the same property. The USSR witnessed various anti-religious campaigns, with Stalin's "Atheist 5-year plan" being especially severe. Churches were destroyed, and religious groups like the Old Believers faced genocide.

Even in Maoist China, traditional aspects of Chinese society were systematically dismantled. The fervor for iconoclasm was so extreme that it eventually led to criticism of Mao and other senior leaders of the Chinese Communist party due to perceived compromises. While a comprehensive exploration of these events is beyond the scope of this discussion, even a surface-level analysis reveals the absurdity of characterizing the communists as conservative or traditional. The communists held an atheistic, materialistic worldview that was fundamentally modernist and opposed to nationalistic ideals in every way.

Quoting the Communist manifesto:

“In bourgeois society, therefore, the past dominates the present; in Communist society, the present dominates the past.”

— Karl Marx, Communist manifesto

Marxism, in its revolutionary nature, rejects the preservation of any aspect of life and emphasizes constant change. It focuses on the process of transformation rather than the static state of existence, making it a highly modernist ideology. Conversely, traditional or conservative philosophy takes a different stance on modernism. Julius Evola, a prominent figure in traditional philosophy, portrays a continuous spiritual decline and deterioration that pertains to the highest, spiritual dimension of humanity, rather than a superficial and materialistic one. Marxist historiography, influenced by Enlightenment philosophy, advocates for an unending linear progression from primitivism to slave societies, feudalism, capitalism, and ultimately socialism leading to communism. This notion of "progress" is rooted solely in a materialistic and bourgeois framework, drawing heavily from Enlightenment ideas that predate Marx himself.

Even the contemporary Marxist writer, Chris Cutrone admits:

“But such consciousness of history [as the story of human freedom] was not at all original to Marxism but rather had roots in the antecedent development of the self-conscious thought of emergent bourgeois society in the 18th century, beginning with Rousseau and elaborated by his followers Kant and Hegel. The radicalism of bourgeois thought conscious of itself was an essential assumption of Marxism, which sought to carry forward the historical project of freedom.... Rousseau wrote that while animals were machines wound up for functioning in a specific natural environment, humans could regard and reflect upon their own machinery and thus change it. This was Rousseau’s radical notion of “perfectibility” which was not in pursuit of an ideal of perfection but rather open-ended in infinite adaptability . This was the new conception of freedom, not freedom to be according to a fixed natural or Divine form, but rather freedom to transform and realize new potential possibilities, to become new and different, other than what we were before.”

— Chris Cutrone, Rousseau, Kant and Hegel

An example illustrating this can be found in the praise given by Marx and Lenin to the Jacobins, whom Haz perceives as "the true patriots."

“Bourgeois historians see Jacobinism as a fall ("to stoop"). Proletarian historians see Jacobinism as one of the highest peaks in the emancipation struggle of an oppressed class. The Jacobins gave France the best models of a democratic revolution and of resistance to a coalition of monarchs against a republic. The Jacobins were not destined to win complete victory, chiefly because eighteenth-century France was surrounded on the continent by much too backward countries, and because France herself lacked the material basis for socialism, there being no banks, no capitalist syndicates, no machine industry and no railways. “Jacobinism” in Europe or on the boundary line between Europe and Asia in the twentieth century would be the rule of the revolutionary class, of the proletariat, which, supported by the peasant poor and taking advantage of the existing material basis for advancing to socialism, could not only provide all the great, ineradicable, unforgettable things provided by the Jacobins in the eighteenth century, but bring about a lasting world-wide victory for the working people.”

— Vladimir Lenin, Can “Jacobinism” Frighten The Working Class?

"And what was the Napoleonic government? A bourgeois government which strangled the French Revolution and retained only those results of the revolution which were advantageous to the big bourgeoisie."

— Jospeh Stalin, Mastering Bolshevism

Jay Bergman provides a comprehensive analysis of Marx's perspective on the French Revolution, stating:

“In short, Marx apotheosized the French Revolution for the same reason Edmund Burke loathed it—because it was the result of human agency that caused an entire country—or at least a significant percentage of its inhabitants—to reject the accumulated experiences, traditions, and patterns of life that had existed for centuries.”

— Jay Bergman, The French Revolutionary Tradition in Russian and Soviet Politics, Political Thought, and Culture

Lecture by Professor Harry Oldmeadow

The concept of infinite progress lies at the core of Marxism. In the context of the French Revolution, the traditional monarchy and its accompanying aristocracy were overthrown, and a Republic was established. This marked a radical departure from the old feudal social structures, with the Jacobins being particularly fervent advocates of these revolutionary changes. Those associated with the old traditional order were executed by the revolutionaries in France.

Lenin, who admired the Jacobins, implemented similar measures against the monarchy during the Russian Revolution. The Russian Empire underwent a revolution that dismantled the entire institution of monarchy and church, followed by a subsequent revolution in October of the same year, which resulted in the execution of Tsar Nicholas and his family. Many aristocrats were killed or forced into exile, while those who remained endured persecution or concealed their backgrounds.

Communist China also adopted comparable measures, demonstrating the iconoclastic nature of Marxist-Leninist ideology. For instance, the Chinese Communist party, under Mao's leadership, attempted to execute Emperor Puyi. This exemplifies how the existence of a monarchy implies societal class divisions. Even if the monarch holds a symbolic role, as seen with the last Emperor of China, the figurehead represents reaction and serves as a target for communism's inherent iconoclasm and revolutionary spirit, aimed at overturning the traditional social orders of the feudal system.

The last Queen of Mongolia, moments before she was executed by the USSR, 1938

Additionally, in a manner similar to China, the Soviets, after establishing themselves as the ruling government of Russia, proceeded to abolish the entire system, including laws, institutions, and structures inherited from the Russian Empire. This lack of direct continuity with the previous regimes exemplifies another instance of political iconoclasm within the Soviet Union. In Frederick Engels' work, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, he suggests that property plays a pivotal role in the creation of the traditional family and, consequently, in modern civilization. Engels views the family as a construct of the bourgeois society. This raises the question of what would happen to the institution of the family under Communism. To gain insights, we can refer to the Communist manifesto:

“[Communism] will transform the relations between the sexes into a purely private matter which concerns only the persons involved and into which society has no occasion to intervene. It can do this since it does away with private property and educates children on a communal basis, and in this way removes the two bases of traditional marriage – the dependence rooted in private property, of the women on the man, and of the children on the parents.”

— Karl Marx, Communist manifesto

This was seen, for instance, in studies of the modern Chinese family by Zeng Yi at Beijing University. He found that the shape and structure of families had changed radically under Communist rule. The Infrared Collective may hold a different perspective, but it is evident that certain changes occurred in relation to family dynamics. In China, during the Cultural Revolution and the Maoist era, the family size decreased, intergenerational living became less common, and divorce rates rose. Zeng Yi attributes these changes to the policies implemented during that time, which challenged the long-standing traditions of family piety and Confucian family structures.

In the Soviet Union, the goal was to gradually phase out the institution of the family. Alexander Goikhbarg, a prominent legal jurist, regarded the family as a temporary social arrangement that would eventually be replaced by a communal system supported by the state, leading to the eventual "withering away" of the traditional family structure. The jurists aimed to provide protections for women and children until a comprehensive system of communal support could be established, ultimately abolishing the traditional family.

The 1936 legal code, led by Stalin, introduced a wave of pro-family propaganda. It included measures such as restrictions on abortion, penalties for those involved in providing or receiving abortion services, and laws promoting pregnancy and childbirth. The code also made it more difficult to obtain a divorce, requiring both parties to be present and imposing fines. Harsh penalties were imposed for failure to pay alimony and child support. The government's campaign to encourage the family elevated motherhood as a patriotic duty, emphasizing the joys of children and family.

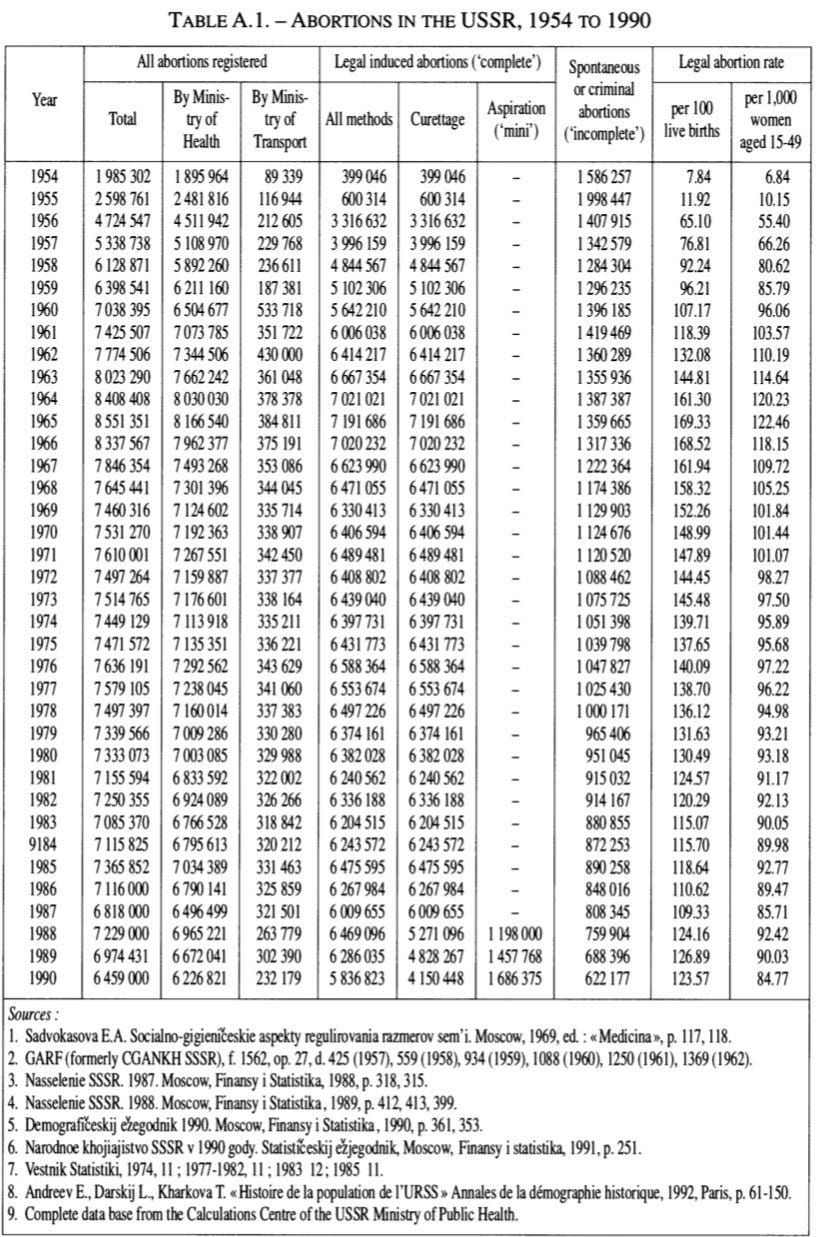

While these reforms may be interpreted as having conservative elements, their motivation stemmed from the recognition by senior Bolshevik Party officials in the 1920s that a stable family life was necessary to rebuild the country's economy and social structure after the Russian Civil War and the destabilization of family units. After Stalin's death in 1953, the Soviet government revoked some natalist legislation, legalizing abortions for medical reasons in 1955 and extending the legalization of all abortions in 1968. Divorce procedures were also liberalized in the mid-1960s. Maoist China followed a similar trajectory in these regards.

Abortions in the USSR from 1954 to 1990

Communist countries, to the extent that they could be considered "conservative," deviated from Marxist theory in response to political realities that necessitated the maintenance of their social orders. This brings us to the concept of opportunism, where these countries would selectively challenge traditionalism only if it did not disrupt stability. Contrary to popular perception, these countries were not primarily conservative, but rather reactionary in nature, responding to challenges on a utilitarian basis. They would embrace the logic of capital and target traditional institutions as prescribed by Marxist theory whenever possible. However, when faced with practical circumstances, such as the need to win a World War, they would temper some of the excesses associated with their ideology. Ultimately, the inspiring battle cry of "For the Motherland" carries far greater resonance than the abstract concept of "For Dialectical Materialism."

Reactionary Socialism vs Marxist Socialism

Oswald Spengler, a prominent traditionalist philosopher-historian, held an inherently anti-capitalist stance. He, along with other traditionalists, saw capitalism and the rise of the bourgeoisie as agents of destruction that undermined the foundations of traditional order, similar to Marx. The critical distinction, however, lies in their interpretations of this phenomenon. Marxists viewed capitalism as a necessary stage in historical progression, whereas traditionalists like Spengler saw it as a symptom of societal decline.

Western Civilization often prides itself on its economic activity, considering it the epitome of "progress." This perspective is rooted in the illusion of linear evolution. The stark contrast between the modernist and traditional conservative perceptions of life is poignantly captured in the ebullient optimism expressed by 19th-century biologist Dr. A.R. Wallace in his work, The Wonderful Century.

“Not only is our century superior to any that have gone before it but . . . it may be best compared with the whole preceding historical period. It must therefore be held to constitute the beginning of a new era of human progress…. We men of the 19th Century have not been slow to praise it. The wise and the foolish, the learned and the unlearned, the poet and the pressman, the rich and the poor, alike swell the chorus of admiration for the marvelous inventions and discoveries of our own age, and especially for those innumerable applications of science which now form part of our daily life, and which remind us every hour or our immense superiority over our comparatively ignorant forefathers”

— Dr. A.R. Wallace, The Wonderful Century

Both Marx's belief in Communism as the ultimate stage of human existence and the capitalist worldview share a common belief in the inexorable progress of a technical nature. In both ideologies, this progress represents the culmination of history, or what is often referred to as the "end of history." However, the traditionalist perspective diverges significantly from this linear view. Traditionalists see history not as a linear progression from primitive to modern, but rather as a continuous cycle, akin to the ebb and flow of ocean tides. This cyclical understanding of history recognizes the constant flux and repetition of patterns throughout time.

As Alexander Dugin put it:

“Instead of growth, progress, and development, there is life. After all, there has been no proof offered yet to show that life is linked to growth. This was the myth of the Nineteenth Century.… There is no life without death. Being-towards-death… is not a struggle with life, but, rather, its glorification and its foundation.”

— Alexander Dugin, The Fourth Political Theory

While Marx's concept of the "wheel of history" propels society forward, disregarding tradition and heritage until it reaches a final destination of a monotonous, sterile world of concrete and steel, the traditionalist understanding of the "wheel of history" revolves in a cyclical manner around a stable axis. Oswald Spengler, for instance, describes the later era in this cyclic model:

“And now the economic tendency became uppermost in the stealthy form of revolution typical of the century, which is called democracy and demonstrates itself periodically, in revolts by ballot or barricaded on the part of the masses. In England, the Free Trade doctrine of the Manchester School was applied by the trades unions to the form of goods called ‘labour,’ and eventually received theoretical formulation in the Communist Manifesto of Marx and Engels. And so was completed the dethronement of politics by economics, of the State by the counting-house….”

— Oswald Spengler, The Hour of Decision

Spengler refers to Marxist forms of socialism as "capitalistic" because they do not seek to replace the values based on money but rather aspire to acquire them themselves. For instance, Marx's discussion of free trade highlights this perspective:

“Generally speaking, the protectionist system today is conservative, whereas the Free Trade system has a destructive effect. It destroys the former nationalities and renders the contrast between proletariat and bourgeois more acute. In a word, the Free Trade system is precipitating the social revolution. And only in this revolutionary sense do I vote for Free Trade.”

— Karl Marx, On The Question of Free Trade

Marx viewed capitalism as an integral part of an unstoppable dialectical process. Similar to the progressive-linear view of history, Marx saw humanity evolving from primitive communism and slave societies, through feudalism and capitalism, towards socialism, and ultimately reaching a millennial state of Communism, which he considered the ultimate endpoint of history. Throughout this dialectical and progressive unfolding, the driving force behind historical change is the class struggle for the dominance of specific economic interests. In Marx's economic reductionist perspective, history is primarily defined by this struggle:

“[The struggle between] freeman and slave, patrician and plebeian, lord and serf, guild master and journeyman, in a word, oppressor and oppressed in constant opposition to one another, carried on uninterrupted, now hidden, now open, a fight that each time ended, either in a revolutionary re-constitution of society at large, or in the common ruin of the contending classes.”

— Karl Marx, Communist manifesto

Marx accurately describes the inherent destruction of traditional society within capitalism and also discusses what we now refer to as globalization. It is noteworthy that Marx supported free trade and considered it both "destructive" and "revolutionary." He viewed free trade as a necessary component of the dialectical process that imposes universal standardization, which aligns with the goals of Communism. Expanding on the dialectical role of capitalism, Marx asserts that wherever the bourgeoisie, or merchant class, gains dominance, it dismantles feudal, patriarchal, and idyllic relationships. The bourgeoisie ruthlessly severs feudal bonds, leaving only self-interest and monetary transactions as the nexus between individuals. It extinguishes religiosity and chivalry, replacing them with the cold calculations of egotistical gain. Personal worth is reduced to exchange value, and countless freedoms are replaced by the unfettered freedom of Free Trade.

The conservative does not necessarily oppose Marx's depiction of how capitalism functions; rather, the conservative must oppose Marx's positive evaluation of this system as both inevitable and desirable. Marx condemns opposition to this dialectical process as "reactionary." He perceives the constant revolutionizing of the means of production as an inherent aspect of capitalism, leading society into a perpetual state of uncertainty and agitation that distinguishes the bourgeois era from others. The "need for a constantly expanding market" drives capitalism to spread globally, imparting a cosmopolitan character to modes of production and consumption in every country. According to Marxist dialectics, this process is essential for eroding national boundaries and distinctive cultures, paving the way for world socialism. Capitalism establishes the foundation for internationalism.

Marx discusses the manner in which traditional rural structures succumb to urbanization and industrialization, giving rise to the proletariat, a rootless mass upheld by socialism as an ideal rather than a corrupt deviation. Traditional societies are deeply rooted in blood and soil. However, capitalism renders village life and localized existence obsolete, as Marx refers to the dominance of cities and mass production. The rise of the city, coupled with the ascendancy of merchants, is seen by traditionalists like René Guénon as a symptom of civilization's decay in its sterile phase, where monetary values reign supreme.

Marx notes the creation of "enormous cities," which Spengler refers to as "Megalopolitanism." What sets Marx apart from traditionalists is his embrace of this destructive aspect of capitalism. While discussing urbanization and the alienation of former peasants and artisans as they become proletarianized in cities, Marx does not view this process as something to resist. Instead, he sees it as inexorable and even lauds it for rescuing a significant portion of the population from the perceived ignorance of rural life.

The peasantry is depicted as condemned to proletarian dispossession until it recognizes its historical role as a revolutionary class and "expropriates the expropriators." This "peasant class" can either escape purgatory by joining the ranks of the chosen proletarian people, participating in the socialist revolution, and entering a new era, or it can descend from its purgatory if it insists on maintaining the traditional order, leading to oblivion. This perspective helps explain why the Bolsheviks massacred peasants or forced them into urban areas. The same principle applies to the middle class.

Marx highlights in the Communist manifesto that reactionaries view the dialectical processes of capitalism with great dismay. The reactionary, or the traditionalist conservative, stands as the ultimate anti-capitalist figure because they transcend the zeitgeist from which both capitalism and Marxism emerged. They wholly reject the economic reductionism upon which both ideologies are founded. Both conservatives and Marxists acknowledge the destructive and revolutionary nature of capitalism. However, for conservatives, this is seen as a detriment, while for Marxists, it is viewed as a positive aspect that paves the way for a more globalized world, which can serve as a foundation for Communism. Capitalism is seen by Marx and his followers as a betrayal of the bourgeois promise of freedom, which they seek to fulfill.

Rudolf Jung reminds us:

"Socialism and materialism are, after all, simply incompatible, because the former is the highest altruism, while the latter is the most flagrant egotism. And so socialism built upon materialism again ends only in individualism!"

— Rudolf Jung, National Socialism

Ethnos: Marxist Revolt Against The Nation

Marx dedicates section three of his Communist manifesto to the critique of what he terms "reactionary socialism." He vehemently denounces the emergence of "feudal socialism" among the remnants of the old aristocracy, who sought to align themselves with the working class against the bourgeoisie. In Marx's view, the aristocracy, in their attempt to reclaim their pre-bourgeois position, had lost sight of their own class interests by siding with the proletariat.

This organic alliance between the dispossessed professions, which had evolved into the so-called proletariat, and the increasingly marginalized aristocracy, encounters adversaries not only in the form of capitalism but also in Marxism itself. Marx expresses his fury towards the budding alliance between the aristocracy and those professions resisting proletarianization. Thus, Marx condemns "feudal socialism" as a hybrid that echoes remnants of the past while simultaneously posing a threat to the future.

During the revolutionary year of 1848 in Germany, this movement garnered substantial support from craftsmen, clergymen, nobles, and intellectuals. They rejected the free market system, which they believed had severed the connections between individuals and institutions such as the Church, State, and community. Instead, this system prioritized egoism and self-interest over subordination, collective identity, and social solidarity. Max Beer, a historian of German Socialism, refers to these individuals as "reactionaries," a term employed by Marx himself.

“The modern era seemed to them to be built on quicksands, to be chaos, anarchy, or an utterly unmoral and godless outburst of intellectual and economic forces, which must inevitably lead to acute social antagonism, to extremes of wealth and poverty, and to a universal upheaval. In this frame of mind, the Middle Ages, with its firm order in Church, economic and social life, its faith in God, its feudal tenures, its cloisters, its autonomous associations and its guilds appeared to these thinkers like a well-compacted building…”

— Max Beer, The General History of Socialism and Social Struggles

The necessity of forming an alliance encompassing all social classes, an alliance that Marx vehemently labeled as "reactionary," becomes apparent when confronting the subversive forces of free trade and revolution. If conservatives aspire to rejuvenate the cultural organism rooted in traditional values, they cannot achieve this by embracing economic doctrines that fundamentally oppose tradition. Marx, on the other hand, welcomed these economic doctrines as part of a subversive process aimed at dismantling tradition.

Lenin's perspective on the matter sheds further light:

“Although the alliance which has come into being in the Balkans is an alliance of monarchies and not of republics, and although this alliance has come about through war and not through revolution, a great step has nevertheless been taken towards doing away with the survivals of medievalism throughout Eastern Europe. And you are rejoicing prematurely, nationalist gentlemen! That step is against you, for there are more survivors of medievalism in Russia than anywhere else!”

— Vladimir Lenin, A New Chapter of World History

From an organizational standpoint, traditionalists advocated for the use of guilds or corporations, which were perceived as manifestations of the divine order. However, with the demise of traditional societies, these guilds were supplanted by trade unions and professional associations that solely focused on safeguarding the economic interests of their members in relation to other trades and professions. This shift led to the erosion of the sense of duty and responsibility that individuals once embraced as proud members of their crafts, where a code of honor governed their actions. Julius Evola, similar to the corporations of Classical Rome, emphasized that medieval Guilds were founded upon religious and ethical principles rather than economic concerns.

“The Marxian antithesis between capital and labor, between employers and employees, at the time would have been inconceivable.”

— Julius Evola, Revolt Against The Modern World

Alfredo Rocco, an Italian Fascist, expressed the belief that the Guilds, which had been weakened by the rise of individualism and the egalitarian ideals of the French Revolution, could be revived through the social ideals of Italian nationalism. Rocco saw the Guilds as embodying a system that rejected the notion of absolute equality and instead emphasized discipline and the recognition of differences. He believed that the Guilds fostered a genuine and productive sense of camaraderie among different classes, all of whom played a role in the process of production.

The convergence of traditionalist ideas within Fascism served as a driving force for traditionalists like Evola to align themselves with the Axis Powers. They saw in Fascism an opportunity to revive traditionalism. Despite the presence of modernist or nominalistic elements, Fascism embraced an organic understanding of nation-building and ethnic identity, infused with the spirit provided by the Guild model. This was in contrast to Marxism, which did not incorporate such an approach. Fascism's interpretation of Hegelian dialectics resonated with the traditionalist schools' understanding of monism.

Marx himself rejected Hegel's dialectics, perceiving the concept of the "Idea" as having a religious character. He countered this metaphysical "Ideat" with a focus on the material world. Hegel, on the other hand, explored how the historical dialectic operated on the "national spirit." His philosophy aligned with the Rightist doctrinal stream, which gained significant influence from German thinkers as a counter to "English thought" based on economics. This economic foundation permeated Marx's thinking and mirrored the capitalist system.

For instance, Hegel wrote:

“The result of this process is then that Spirit, in rendering itself objective and making this its being an object of thought, on the one hand destroys the determinate form of its being, on the other hand gains a comprehension of the universal element which it involves, and thereby gives a new form to its inherent principle. In virtue of this, the substantial character of the National Spirit has been altered, – that is, its principle has risen into another, and in fact a higher principle.

It is of the highest importance in apprehending and comprehending History to have and to understand the thought involved in this transition. The individual traverses as a unity various grades of development, and remains the same individual; in like manner also does a people, till the Spirit which it embodies reaches the grade of universality. In this point lies the fundamental, the Ideal necessity of transition. This is the soul – the essential consideration – of the philosophical comprehension of History.”

— Hegel, The Philosophy of History

According to Marx and Engels, the concept of the "National Spirit" was a byproduct of bourgeois society. They rejected any ontological or metaphysical basis for nationalism. This viewpoint was echoed by other Marxists, including the Jewish historian Eric Hobsbawm, who argued that national identity emerges within a specific stage of technological and economic advancement, not solely as a result of a territorial state or the desire to establish one.

Contrary to Haz and The Infrared Collective's viewpoint, which asserts that communists should make genuine efforts to express the objectivity of the nation, encompassing its rights, rituals, and the national spirit that defines its people, there are those who may disagree. Marxism has consistently underscored the significance of the global workers' movement, prioritizing it over national interests. In fact, Marxism explicitly challenges the idea that the realities of the nation are immutable, as it asserts that they can indeed be transformed. This perspective is evident in the writings of Marx and Engels, who articulated:

“The nationalities of the peoples associating themselves in accordance with the principle of community will be compelled to mingle with each other as a result of this association and thereby to dissolve themselves, just as the various estate and class distinctions must disappear through the abolition of their basis, private property.”

— Marx and Engels, The Principles of Communism

We observe this continuation of Marxist principles by Lenin. He criticizes the concept of "national cultural autonomy" which divides workers based on their various national cultures, reinforcing ties to bourgeois culture. Instead, Social-Democrats aim to foster an international culture of the world proletariat. Lenin emphasizes the importance of teaching workers to be "indifferent" to national distinctions, but not in a way that supports annexationism. To be an internationalist Social-Democrat, one must prioritize the interests of all nations, their common liberty, and equality, placing them above the interests of one's own nation. He argues that petty-bourgeois nationalism merely pays lip service to the equality of nations and preserves national self-interest, while proletarian internationalism requires subordinating the interests of the proletarian struggle in any one country to the global struggle against international capital. Lenin also criticizes refined nationalism, which seeks to divide the proletariat based on false pretexts such as protecting national culture or autonomy. Class-conscious workers reject all forms of nationalism, including crude and violent nationalism, and advocate for the unity of workers across nationalities within united proletarian organizations.

The quotation emphasizes a contrast between Haz's viewpoint and that of Marx and Lenin. Haz contends that communists should actively express the objectivity of the nation, encompassing its rights, rituals, and national spirit, rather than disregarding them. He argues that the realities of the nation hold significance and cannot be ignored. This contradicts the perspective of Marx and Lenin, who prioritize internationalism and advocate for the subordination of national interests to the broader struggle of the global proletariat.

The conflict between traditionalist understanding and Marxism regarding the concept of the nation can be examined through the perspectives of various thinkers. Nikolay Yakovlevich Danilevsky, a Russian philosopher, categorized historical-cultural activity into religious, political, psychological, cultural, and biological realms. He used biological and morphological metaphors to compare cultures and nations, denying their commonality and arguing that each nation or civilization is defined by its language and culture, which cannot be passed on to other nations. Lev Nikolayevich Gumilyov built upon Danilevsky's ideas, describing the genesis and evolution of ethnic groups, leading to the formation of nations.

Ivan Ilyin extended this hypothesis, presenting a spiritual conception of nations, emphasizing the motherland as a religious shrine and highlighting the connection between patriotism and the flourishing of the Russian spirit. Charles Maurras, another traditionalist, emphasized the importance of ancestry, masters, elders, books, artworks, and landscapes in defining one's identity. These traditionalist perspectives directly contradict the atheistic and materialistic analysis promoted by communism, which aspires to an internationalized, borderless world without national identities. Furthering our point that the traditionalist and conservative understandings of the world are not compatible with the modernist ideas of communism. Just from this the conclusion is clear, communists are not conservatives Haz especially if your ideas are built upon democratic ideas.

“Aristocracy', […] taken in its etymological sense, means precisely the power of the elite. The elite can by definition only be the few, and their power, or rather their authority, deriving as it does from their intellectual superiority, has nothing in common with the numerical strength on which democracy is based, a strength whose inherent tendency is to sacrifice the minority to the majority, and therefore quality to quantity, and the elite to the masses.”

— René Guénon, Crisis of The Modern World

To gain a proper understanding of traditionalism, we must turn to Frithjof Schuon as a prime example, as he epitomizes the essence of traditionalist thought. Schuon identifies modernity as encompassing rationalism, which denies the existence of supra-rational knowledge; materialism, which reduces life's meaning to mere matter; psychologism, which diminishes the spiritual and intellectual realms to the psychic; skepticism; relativism; existentialism; individualism; progressivism; evolutionism; scientism; empiricism; agnosticism; and atheism. These very traits can be found within the philosophy of Marxism. Schuon critiques modern science, despite its remarkable discoveries on the physical plane, for embodying "totalitarian rationalism." This rationalism dismisses both Revelation and Intellect, while simultaneously embracing a materialism that fails to recognize the metaphysical relativity of matter and the world. It overlooks the fact that the supra-sensible, beyond space and time, serves as the concrete principle of the world and, consequently, is the source of that contingent and mutable coagulation known as "matter."

According to Schuon, scientism is plagued by the contradiction of attempting to explain reality without the aid of metaphysics, the foundational science that imparts meaning and discipline to the science of the relative. This perspective of a universe that disregards both the principle of "creative emanationism" and the "hierarchy of the invisible worlds" has given rise to what Schuon deems "the most emblematic offspring of the modern spirit": the theory of evolution, accompanied by the illusory notion of "human progress."

Duginism Is Against Bolshevism

To gain a comprehensive understanding of traditionalism and its implications for nations, it is beneficial to explore the insights of Alexander Dugin, a figure that Haz fails to grasp adequately. Haz has gone so far as to claim that Dugin's Fourth Political Theory is materialistic and Maoist, suggesting that it may actually be a disguised form of Marxism-Leninism. He questions whether this theory aligns with Chinese Communism's constant self-revolutionizing nature, insinuating a connection to Maoism. While I have previously expressed my belief that Dugin's Fourth Political Theory is essentially a variant of Russian Third Positionism, it is important to note that Dugin himself acknowledges the similarities between Neo-Eurasianism and traditionalism or the Third Position. He even asserts that the transition from the European Third Way to the Fourth Political Theory is a mere step. These connections may also shed light on Dugin's associations with individuals such as Franco Freda, a Nazi-Maoist, and Jean-François Thiriart, a former member of the Waffen SS. Furthermore, Dugin's geopolitical framework draws upon two key influences: Heidegger's concept of Dasein and Carl Schmitt's notion of Large Spaces. Although Heidegger's affinity with German Third Positionism raises questions, Schmitt's concept of Large Spaces can be traced back to Hitler himself, as noted by Brendan Simms, a prominent intellectual biographer of Hitler.

“Hitler’s idea of a German Monroe Doctrine–which he had first mentioned more than a decade earlier [in 1923]–was picked up by the lawyer Carl Schmitt, who elaborated it into an entire theory of ‘large spaces.’”

— Brendan Simms, Hitler: A Global Biography

Dugin's geopolitical philosophy draws on two significant influences, one of which can be traced directly to Adolf Hitler himself, while the other has a complex and somewhat ambiguous relationship with the Third Reich. In a Maoist blog interview with Dugin in 2015 (which was even syndicated on one of his websites), he was questioned about Mao and Maoism. His response, highlighted in the original text, is as follows:

“Mao was right affirming that socialism should be not exclusively proletarian but also peasant and based on the ethnic traditions. It is closer to the truth than universalist industrial internationalist version represented by trotskyism. But I think that sacred part in Maoism was missed or underdeveloped. Its links with Confucianism and Taoism were weak. Maoism is too Modern for me. For China it would be best solution to preserve the socialism and political domination of national-communist party (as today) but develop more sacred tradition – Confucianism and Taoism. It is rather significant that ideas of Heidegger are attentively explored now by hundreds of Chinese scientists. I think Fourth Political Theory could fit to contemporary China best of all.”

— Alexander Dugin quoted in Maoism Is too Modern For Me (https://democracyandclasstruggle.blogspot.com/2015/03/maoism-is-too-modern-for-me-says.html?m=1)

In the same interview, Dugin explicitly states that he is not a communist or Marxist, as he rejects any form of materialism and denies the concept of progress. Instead, he identifies his views as being aligned with the Fourth Political Theory and traditionalism. Haz's misunderstanding of Dugin becomes evident when he incorrectly attributes a materialistic metaphysics to Dugin's ideas. Haz suggests that Dugin, influenced by Heidegger, acknowledges the material and objective reality of Russian civilization and geopolitics beyond ideological considerations. Additionally, Haz claims that Dugin's writings are confined to their material foundations, such as geopolitics and the unconscious aspects of Russian civilization. According to Haz, Dugin, like Heidegger, recognizes the inherent ambiguity of material existence. Dugin's philosophical stance is far from being aligned with materialism. It is rather absurd that I have to clarify this point.

In an interview with Michael Millerman, Dugin explicitly addresses this topic:

“In order to get to such understanding of the mystical dimension of the thought, we need to sacrifice materialism... we should recognize this kind of alternative sovereignty of the thought, of the spirit, of the subject. And that is very important. But for me, not being a materialist, that is quite easy.”

— Alexander Dugin, Interview with Alexander Dugin (Philosophy, 4PT, Education, Mysticism, Theatre)

Dugin's perspective diverges significantly from recognizing the "material and objective reality of Russian civilization." Drawing inspiration from Heidegger and, to some extent, Husserl, it becomes apparent through even a brief examination of the Fourth Political Theory that Dugin adopts a phenomenological approach rather than a materialist one. He explicitly rejects all forms of materialism, whether vulgar or dialectical, in favor of an immaterial, phenomenological, mystical, and idealist philosophical framework.

As he articulates in his work Putin vs Putin:

“The Fourth Political Theory can be attributed to the fields of phenomenology, structuralism, existentialism, ethno-sociology and cultural anthropology.”

— Alexander Dugin, Putin vs Putin

The actual material basis of the Russian folk or narod holds little significance in Dugin's perspective. In his ethno-sociological theory, elaborated upon in his book Ethnos and Society, the defining elements of a people are not solely rooted in shared genetic ancestry but rather in the recognition of a common origin, along with shared language and traditions. Dugin does not seek to establish a material foundation upon which a people can be grounded. Dugin and the Fourth Political Theory do not view the nation as an "objective reality." In Volume II of the Fourth Political Theory, in the final appendix, he explicitly distinguishes the nation as a "subjective reality" and contrasts this perspective with the third political theory, which he claims perceives the nation as an "objective reality." His phenomenological and ethno-sociological approaches further emphasize that he is not concerned with the material reality of any particular group of people.

In fact, Dugin even criticizes Vladimir Putin for placing excessive emphasis on the material reality of Russian and Eurasian civilization.

“In my opinion, even Putin’s approach to problems is purely corporeal, much like Epicurus. He sees the population as an aggregate of material objects that one must feed… This is all materialism. Putin suggests uniting the post Soviet landscape in the same way — on a materialistic basis.… I think that it’s necessary to move on to the politics of spirit.”

— Alexander Dugin, Putin vs Putin

A straightforward examination of Dugin's book, a Theory of a Multipolar World, reveals that he does not approach multipolarity from a materialistic standpoint.

“This leads to the most logical conclusion: the economic model of the multipolar world must be based on the rejection of economic-centrism and the reduction of economic factors to a lower level than social, cultural, religious and political factors. Without the relativization of the economy, without the subordination of the material to the spiritual, without the transformation of the economic sphere into a subordinate and secondary one in relation to the dimension of civilization in general, multipolarism is impossible.”

— Alexander Dugin, Theory of a Multipolar World

In his book, Dugin outlines that his geopolitical perspective is rooted in a combination of idealism and holism. He explicitly rejects the materialistic and holistic approach of Marxism, the materialistic and individualistic approach of realism, and the idealistic and individualistic approach of liberalism. According to Dugin, idealism places significant importance on concepts such as theories, ideas, and points of view, surpassing the significance of "matter" or the empirical field, which is considered secondary. Additionally, holism emphasizes the interconnectedness of a whole system, highlighting the inability of individual atomic actors to exist independently. Dugin's civilizational and geopolitical theory draws ontological inspiration from Carl Jung's concept of the Collective Unconscious and Leibniz's Monad, both of which reject materialism.

Contrary to Haz's claim, Dugin clarifies that the narod or volk is not a "material and objective reality." Instead, Dugin explains that the economy and production, often considered as separate domains defined by the material factor, are actually part of the narod's care and existence (Dasein). It is utterly absurd to suggest that Dugin is a materialist or advocates for Marxist-Leninist-Maoist ideologies. He has consistently and explicitly rejected Marxism and all forms of materialism in his writings and speeches.

Haz's claim that Dugin, a committed adherent of Orthodox Christianity with a strong connection to tradition, is excessively focused on materialism, is a disrespectful distortion that reveals Haz's limited comprehension of Dugin's philosophy. Dugin does not view historically self-proclaimed Marxist regimes as genuinely adhering to Marxism. Rather, he labels them as instances of "National Communism." According to Dugin, National Communists purport to embrace orthodox Marxism and draw inspiration from Communist classics, but in truth, they have adopted nationalistic elements or aspects of tradition to ensure their survival.

In seeing how these regimes took certain nationalistic, patriotic, and various traditionalist trappings (however superficial), he notes in Volume II of The Fourth Political Theory:

“In communist regimes, Marxism was not what it proclaimed to be, but was rather a model of exogenous modernization in which Western values were adopted only partially and were tacitly combined with local religious-eschatological and messianic tendencies. On the whole, this procedure of specific modernization -- alter-modernization along the socialistic (totalitarian), but not capitalistic (democratic) path -- served for the defense of the geopolitical and strategic interests of independent states, which were striving to repel the colonial attack of Europe and (later) America.”

— Alexander Dugin, Fourth Political Theory

In his book Last War of The World Island, Dugin highlights that as of May 1924, Joseph Stalin adhered to the orthodox Marxist perspective, which was sometimes derogatorily referred to as "Trotskyism" by some individuals. Stalin initially rejected the notion of "socialism in one country." It was only towards the end of 1924 that Stalin veered away from orthodox Marxism and began pursuing the project of "National Communism," although this shift was implicit rather than explicitly stated.

Conclusions

Marxism represents the ideology of the bourgeoisie, a perspective that looks to the past and aims to shape the future based on a bourgeois-centered worldview, intertwining concepts of class and progress. Ernst Jünger, a German conservative, astutely observes in his book The Worker that Marxism envisions "communism" as a more advanced form of bourgeois society. It is clear that individuals like Haz, who promote the idea of "Conservative Communism," are trying to deceive the Dissident Right into embracing a communist revolution. This opportunistic pragmatism is the true threat posed by Haz and his agenda. The Marxist criticism of Haz's push towards a right-wing direction is clearly misguided.

This approach serves to divert support from the right and effectively neutralize any right-wing or nationalist alternatives. Some communists mistakenly view Haz as a hidden Fascist, and I, too, fell for this misconception during our debate when I mentioned the idea of "Red-Brown" unity. However, his objective is not that. Haz's political maneuvers are merely a tool to achieve his ultimate goal: promoting a bourgeois worldview and instilling a red specter of terror.

Dugin aptly reminds us:

"Soviet socialism's disdain for the spirit and for religion, its atheism and hatred for history — it was this fact and no other which became the chief misfortune of Russian Bolshevism and let ultimately to its death — were manifested for the communists in their explicit hatred of the peasantry. The majority of orthodox Marxists unilaterally saw the peasants as a reactionary class (in this surmise, they were correct). A lack of Orthodox Christianity and a disdain for the peasants were the most negative features of Soviet socialism."

— Alexander Dugin, The Royal Labor of The Peasant

Based. Haz is absolutely decimated here and will never recover from this massive L.