Defending Maduro

by Zoltanous

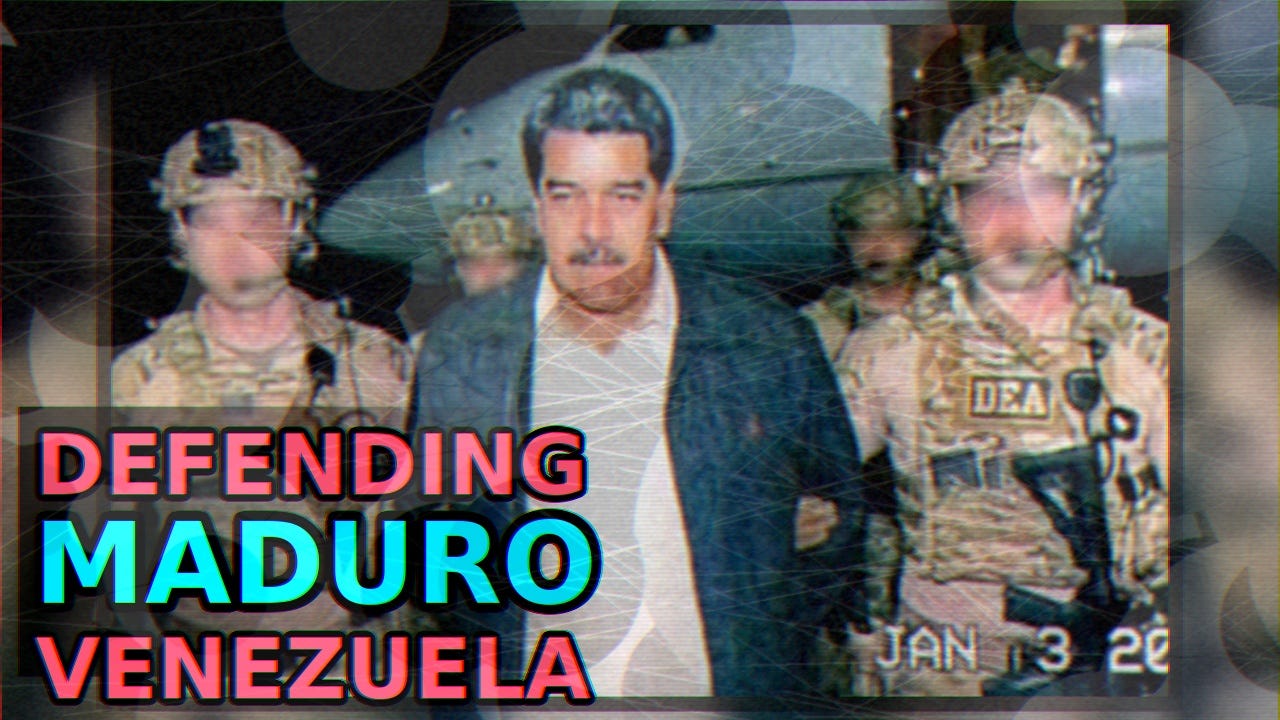

On January 3, 2026, the United States seized a sitting head of state on Venezuelan soil and flew him to New York to face U.S. charges. That is the fact pattern that matters, because it is the hinge on which every other talking point swings. If you normalize cross border abductions wrapped in the language of “law enforcement,” then every accusation becomes a license and every rival state becomes a future crime scene. You do not get a rules based order out of that. You get a world where power writes warrants for itself.

“All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.”

— United Nations, Charter of the United Nations (Article 2(4))

That is not a rhetorical flourish. It is the foundational prohibition. The entire interventionist story tries to dodge this by narrating Venezuela as a criminal enterprise rather than a state and by narrating the raid as “justice” rather than force. But international law does not vanish because Washington dislikes a government. Even the UN Secretary General, responding to this capture, warned about legality and precedent, precisely because this is the kind of action that detonates norms and invites reciprocity. Now, the pro intervention narrative leans on three stacked claims. First, that Venezuela’s collapse is mainly self inflicted. Second, that the refugee crisis is therefore a moral permission slip for coercion. Third, that the U.S. is acting defensively, not hegemonically, because it is supposedly fighting drugs, terrorism, and a hostile axis.

Start with the part that is true, because a defense that cannot concede reality is propaganda. Venezuela did suffer from real corruption, distorted incentives, and policy failures. The Chávez era built a political economy where oil rents substituted for accountable institutions. The state expanded as a dispenser of patronage, and competence often lost to loyalty. The PDVSA chaos after the 2002 to 2003 strike was catastrophic, and the expulsion of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration in 2005 was a watershed in the way the “drug war” narrative would later be weaponized in both directions. Reuters reported that Chávez ended cooperation with the DEA amid claims of espionage and sovereignty violations. But the argument stops being analysis the moment it pretends these internal failures authorize an external battering ram. Economic collapse does not suspend sovereignty. Corruption does not transfer jurisdiction. And “narco state” is not a magic phrase that turns military power into a court order.

The real sleight of hand is the timeline. The story often reads as if Washington patiently watched Venezuela implode, offered off ramps, and only then escalated. That framing is false by omission, because it severs cause from effect. The United States did not merely “respond” to Venezuela’s crisis. It applied accelerants to it, then used the fire as proof that the building needed to be kicked down. The U.S. sanctions regime is the central accelerant and this is no longer a matter of partisan debate. The U.S. Government Accountability Office, hardly a radical source, states that experts and literature it reviewed found sanctions had a negative impact, while noting it can be hard to isolate effects from other factors. More importantly, it explains the mechanism: sanctions constrained oil revenue, pushed crude to fewer buyers at steep discounts, increased transport costs, and reduced access to diluents needed to move and refine heavy crude. In a petro state, choking the export artery is not a “targeted” pressure point. It is systemic asphyxiation.

“According to experts we interviewed and literature we reviewed, U.S. sanctions have had a negative impact on the already declining Venezuelan economy.”

“The U.S. sanctions likely contributed to the decline of the Venezuelan economy, mainly by further limiting its revenue from crude oil exports.”

— U.S. Government Accountability Office, GAO 21 239

If you accept that, then you cannot honestly treat the humanitarian collapse and the migration wave as independent proof that harsher pressure was “working.” They were, in significant part, the predictable consequence of a policy designed to constrict the country’s ability to earn, import, and stabilize.

This is where the refugee talking point gets inverted. The pro-intervention line says: nearly 8 million people fled, therefore removing Maduro is liberation. That is narrative alchemy. The displacement is real and the pain is real, but the question is what drove the surge and when. Reuters has repeatedly pegged the exodus at roughly 7.7 million since 2014, and it is widely tracked by UN agencies and regional platforms. But treating sanctions as a footnote is no longer credible. Francisco Rodríguez’s work is explicitly about how U.S. sanctions policy affects Venezuelan migration flows, because the flows respond to economic suffocation. So when Trumpist MAGA commentary celebrates the refugee crisis as proof of a tyrant’s guilt and then uses it as a justification for regime removal, it is pulling a trick: it treats a sanctions worsened humanitarian outcome as a moral weapon for further coercion. First squeeze the economy. Then point at the suffering. Then demand capitulation. That is not compassion.

Next comes oil. The claim that Venezuela’s oil is the strategic prize is dated. The United States can and does export massive volumes of petroleum and energy. The Energy Information Administration notes that in 2020 the U.S. became a net exporter of petroleum for the first time in decades and that exports have remained high in subsequent years. Even the GAO found sanctions on Venezuelan oil had limited impact on the U.S. oil industry, with refineries shifting to alternatives and no substantial gasoline price spike attributable to sanctions alone.

“In 2020, the United States became a net exporter of petroleum for the first time since at least 1949.”

— U.S. Energy Information Administration, Oil and petroleum products explainer

That does not mean oil is irrelevant. It means oil is not the necessity that justifies the extremity. Venezuela’s oil matters as leverage and as a chokepoint in a wider contest, not as a lifeline for an energy starving America. The point is dominance: who can sell, who can buy, who can finance, who can insure shipping, who can access refineries, who can transact in dollars, who must ask permission. That is why sanctions target not only barrels, but the financial plumbing around barrels. This is also where China and Russia enter, not as window dressing but as the strategic frame. The U.S. does not need Venezuelan oil to run cars; it wants to ensure that rival blocs cannot use Venezuela as a platform to bypass U.S. controlled systems. The sanctions itself, as described in U.S. government reporting, pushes Venezuela to seek diluents, financing, and outlets elsewhere, including Russia and China. The pressure campaign is therefore inseparable from hemispheric dominance. It is the Monroe Doctrine modernized into payment rails, shipping lanes, and extraterritorial law.

Now consider the long catalogue of criminal allegations: Cartel of The Suns, multi-ton shipments, the nephews case, the 2020 indictment, the claim of coordination with FARC, and the more sensational claims about Hezbollah and Hamas training camps and a “terrorist axis.” A serious defense does not pretend Venezuela has no criminality. It refuses the conversion of allegations into casus belli. The U.S. Department of Justice can indict foreign officials. It can also extract plea deals and cooperation. But indictments are not verdicts and U.S. courts are not the world’s courts. When a narrative quotes an Attorney General press line about “flooding the United States with cocaine,” it is quoting prosecution rhetoric, not adjudicated fact. It is also quietly skipping the U.S. history of selectively applying “narco” labels to enemies while partnering with traffickers when it suits geopolitical aims. The drug war has never been a pure moral crusade, it has been a tool. And even if every allegation were true, the leap still fails: none of it grants the United States the legal right to conduct airstrikes and abductions in Caracas. That is why the U.S. tried to frame this as self-defense under Article 51 at the UN. It is also why critics around the Security Council condemned the action as a violation of sovereignty and international law. The legal argument is being stress tested in real time, because if it stands, it becomes a template.

This is where the “graduated response” story breaks down. The U.S. did not simply sanction and wait. It built a coercive ladder: designations, indictments, rewards, maritime pressure, and now kinetic action. In that ladder, humanitarian suffering becomes both collateral and leverage. The GAO itself notes sanctions were meant to respond to the Venezuelan government’s activities, while also acknowledging negative impacts on the economy and humanitarian channels. The ladder is not an unfortunate side effect. It is the strategy. And notice another contradiction that the pro-intervention account tries to bury: it claims the U.S. avoided war because it did not want instability, then celebrates an operation that is inherently destabilizing, because it treats instability as acceptable if it breaks the targeted government. That is why the UN Secretary General highlighted regional instability risk. The idea that a forced decapitation produces a clean democratic transition is fantasy. Venezuela is not a board game.

What about the claims of elections being neither free nor fair, the creation of parallel institutions, the repression of protests, and political arrests? There is ample documentation that Venezuela has experienced severe democratic backsliding and abuses. Human Rights Watch has documented political prisoners and repression patterns, and international reporting has covered the 2024 election dispute extensively. A defense of Venezuela does not require denying these realities. It requires refusing the imperial conclusion that the remedy is an external raid.

This is the key distinction: criticism is not consent to conquest. A country can have a compromised democracy and still retain sovereignty. Its people can deserve better governance and still reject foreign regime change. The pro-intervention narrative pretends those cannot coexist, because it needs moral monopolization. It needs to say: either you cheer the raid, or you are an “apologist.” That is not politics, that is coercive dogma.

Now the corruption set pieces. Specific corruption cases, like those involving currency controls and bribery schemes, have been litigated in U.S. courts and reported in detail, including cases tied to figures like Raúl Gorrín and others involved in exploiting preferential exchange rates. Those cases are real. They illustrate how a dual exchange rate system can become a theft machine. But again, the narrative uses these cases as a morality play to justify collective punishment. Corruption becomes a reason to sanction an entire economy, not merely prosecute specific individuals. Then sanctions worsen scarcity and inflation dynamics. Then scarcity becomes proof of misrule. The circle closes and calls itself justice.

Even the hyperinflation story is often told in a way that scrubs out the external choke. Yes, reckless monetary financing mattered. Yes, price controls and currency distortions mattered. Yes, PDVSA mismanagement and underinvestment mattered. But sanctions hit the state’s ability to earn and to transact and they complicated imports, credit, and oil sector operations. That does not “excuse” mismanagement. It contextualizes collapse. The famous “average Venezuelan lost over 20 pounds” point is a human tragedy, not a propaganda trophy. Reuters reported survey findings on widespread weight loss during the worst shortages. But if you use that suffering to justify more coercion, you are not talking about human rights. You are using bodies as evidence exhibits for a geopolitical case.

So why is Washington doing this if it is not “for oil”? The answer is not that oil is irrelevant. It is that oil sits inside a broader project: hemispheric command, deterrence of rival blocs, and the demonstration effect. Venezuela is a test case for whether a U.S. designated enemy government can survive financial strangulation, diplomatic isolation, and now direct force. It’s a test case for whether extraterritorial prosecution can be fused to kinetic action under the banner of “law enforcement.” This is also why the narrative drags in “Zionist interests” and Middle East proxies. The more you can fuse Venezuela to a global enemy web, the easier it is to sell escalation as defense rather than domination. It is the same rhetorical views used elsewhere: take a regional conflict, weld it to terrorism, then claim the right to strike anywhere. Whether every claimed link is solid or not is almost secondary to the propaganda function.

What should a principled position look like, if you want to defend Venezuela without turning it into a saint? It looks like this, prosecute real crimes through lawful channels, not raids. Target culpable individuals with due process, not entire populations with economic siege. Support negotiated, Venezuelan led political settlement, not externally imposed “transitions” supervised by aircraft carriers. Admit that corruption and misrule exist, while also admitting that sanctions and coercion magnified collapse, aggravated migration, and transformed humanitarian misery into leverage.

Finally, on the claim that Maduro’s capture is “liberation” for the diaspora, diaspora joy is understandable. People who suffered want an ending. Reuters described celebrations among Venezuelans abroad following Maduro’s removal and that emotional reaction is real. But emotion does not settle legality, and it does not guarantee outcomes. In fact, domestically this kind of raid can produce the opposite of “liberation” politics. It has galvanized his base, unified factions that were previously divided, and radicalize parts of the population around a siege narrative, where national pride and resentment override the regime’s failures. Even Venezuelans who despise Maduro can recoil at the precedent of a foreign force snatching their head of state and that backlash can translate into street mobilization, insurgent sympathies, or a harder, more paranoid security state. Many interventions have been greeted with hope and ended in ruin. The question is not whether Maduro is good. The question is whether a world where powerful states can abduct leaders from weaker states is survivable. If the principle becomes “we can seize you because we indicted you,” then the only real law is hierarchy. Then the hemisphere does not become freer, it becomes a map of jurisdictions drawn by force.