Introduction

The intricate relationship between feminism and fascism demands meticulous scrutiny, challenging entrenched beliefs and revealing a historical convergence often obscured from contemporary discourse. Early suffragettes' engagement with fascist movements in Italy, Germany, and Britain unveils a lesser-known facet of history, underscoring feminist endeavors within these spheres that defy simplistic categorization. Dispelling misconceptions surrounding fascism's stance on women's rights becomes imperative in light of pervasive misinterpretations fueled by ignorance or animosity, especially among modern adherents of fascist ideology.

Fascism, despite its quasi-conservative tendencies, did not universally oppose feminist ideals or rigidly enforce traditional gender roles, instead harboring progressive elements that advocated for female workforce participation, maternal support systems, and women's inclusion in governance structures. This nuanced understanding reshapes our perception of the interplay between feminism and fascism, illuminating a diverse spectrum of engagements that challenge simplistic narratives. By scrutinizing the progressive reforms championed by select factions within fascist movements, particularly in relation to gender issues, a deeper understanding of the era's sociopolitical complexities emerges, urging a reevaluation of historical intersections that shape contemporary perceptions of gender, politics, and societal transformation.

Italian Fascism

Historical records reveal that numerous early feminists in Italy were integral to the rise of Fascism. These women were deeply engaged with the squadristi, militant groups known for their revolutionary zeal. A distinguished figure among them was Inés Donati, a young and active member of the Italian Fasces of Combat, a group notorious for their aggressive confrontations with communist groups. In 1921, Donati dedicated herself to volunteer service for the Fascist cause and played a key role in the promotional campaigns for Fascist politicians. She often encountered hostility from those opposing Fascism, yet she remained undeterred, showcasing a commendable level of bravery and steadfastness amidst threats.

Donati was part of a paramilitary contingent, largely comprising squadrismo affiliates from Central Italy, which effectively took control of Rome during a significant general strike orchestrated by anti-Fascist elements. Her involvement extended to participating in emergency aid efforts and she was one of the exceptional women to join the pivotal March on Rome orchestrated by Fascists. In 1923, demonstrating her continued commitment, she sought membership in the newly established Blackshirts Voluntary Militia for National Security, a paramilitary organization.

Mussolini said this about her:

"I have known of her fame for a long time and know that she is a fierce Italian, an indomitable fascist.”

— Benito Mussolini quoted in Mussolini and Fascist Italy by Martin Blinkhorn

In 1924, Inés Donati's health deteriorated, leading to her tragic death at the young age of 24 from tuberculosis on November 3rd in Matelica. Following her death, she was hailed as a martyr by the fascist party. In a gesture of commemoration, Donati's remains were exhumed on March 23rd, 1933, and reinterred at the Chapel of Heroes in the Verano cemetery in Rome, signifying her as a symbol of youthful commitment. Additionally, in 1926, a health clinic in Matelica was named in her memory. A bronze statue was erected to honor her legacy on October 17th, 1937, but it was unfortunately dismantled during the partisan resistance activities in 1944.

The International Feminist Congress was hosted in Rome in 1922, with the backing of the National Fascist party. Benito Mussolini himself made an appearance at the congress, delivering an address that supported the active political engagement of women, reflecting an encouraging attitude towards female political involvement.

Mussolini at the Feminist congress

On the 2nd of June, 1923, Benito Mussolini gave an important address at the opening of the Women's Fascist Congress in Padua.

“Fascisti do not belong to the multitude of flops and sceptics who mean to belittle the social and political importance of women. What does the vote matter? You will have it! But even when women did not vote and did not wish to vote, in time past as in time present, women had always a preponderant influence in shaping the destinies of humanity. Thus the women of Fascism, who bravely wear the glorious “black shirt,” and gather around our standards, are destined to write a splendid page of history, to help, with self-sacrifice and deeds, Italian Fascism.”

— Benito Mussolini, Mussolini as Revealed In His Political Speeches (November 1914 - August 1923)

Fascism played a significant role in the formation of women-only groups known as the Women's Leagues. The first Women's League was established in Milan in 1919, and similar groups emerged shortly thereafter. The transformation of these feminist organizations into supporters of Fascism has been a topic that Italian historians have approached with caution. Prior to the rise of Fascism, women's issues were not a central focus of government policies. However, as early as 1919, the first Fascist manifesto of San Sepolcro, published in Il Popolo D'Italia, already pledged to grant women the right to vote. This promise attracted many feminists who subsequently aligned themselves with the Fascist movement.

“Universal suffrage polled on a regional basis, proportional representation and voting and electoral office eligibility for women.”

— Filippo Tommaso Marinetti and Alceste De Ambris, The Manifesto of The Italian Fasces of Combat

Once in power, Fascism swiftly fulfilled its promise of female emancipation by granting voting rights to women in 1925. Later that same year, the regime initiated the first reform of women's issues with the establishment of "The National Motherhood and Childhood Work." This organization aimed to provide support to mothers and children. In 1927, a campaign was launched to encourage increased birth rates. However, the comprehensive development of mass women's organizations had to be postponed until the early 1930s. Interestingly, one such organization that was promoted by the state was the "Association of Jewish Women of Italy."

To address women's desire for active participation and dedication to the national community, the regime embarked on a delicate balancing act between modernization and emancipation. After 1925, feminists redirected their efforts toward social volunteering and cultural activism, giving rise to a new nationwide feminine subculture. This new form of feminism came to be known as "healthy feminism" in contrast to what was perceived as "vain feminism." As a collective, feminists were generally enthusiastic about Fascism, with very few opposing it, mainly among conservative groups. However, these official women's groups have often been overlooked by historiography in favor of highlighting a narrative of anti-fascism, which portrays Fascism as inherently anti-woman due to its alleged adherence to traditionalism.

Fascism implemented a wide range of maternalistic policies, including the criminalization of abortion, protection and support for maternity, loans for married couples and newborns, career preferences for parents of large families, and the establishment of health and social assistance institutions for families and children.

This Fascist feminism is best summarized by the Italian feminist Laura Casartelli:

“They were authentic for love of the homeland, a long humanitarianism and a lively social sentiment to spingere him to sympathize with the Fascist program of valorization of victory, of exaltation, of the national war."

— Laura Casartelli quoted in Women and Fascism by Martin Blinkhorn

Valentine de Saint-Point, while not a direct participant in fascism, found herself intertwined with the Italian Futurist movement due to her engagement in European artistic circles. In 1912, she made waves with the publication of the Manifesto of Futurist Women, which provoked lively debates across the continent. Her manifesto advocated for the emancipation of women's sexual expression by merging traditionally masculine and feminine traits into one harmonious whole. The influence of her writing spanned wide, with translations spreading her ideas and placing the role of women at the heart of Futurist discourse. Over time, Saint-Point's thoughts contributed to the shaping of an idealized image of women within fascism, eventually leading to the notion of the Donna Fascista.

"A woman who retains a man through tears and sentimentality is inferior to a prostitute who, through bravado, encourages her man to maintain control over the city's underbelly with his revolver at the ready: at least she cultivates an energy that could be directed toward better causes.

Women, who have been diverted for too long by morals and prejudices, return to your sublime instincts—to violence and cruelty.

For the inevitable sacrifice of blood, while men are responsible for wars and battles, procreate, and among your children, as a tribute to heroism, embrace Fate's role. Do not raise them for yourself, which diminishes them, but rather, in expansive freedom, for their full development. Instead of reducing men to the slavery of sentimental needs, inspire your sons and men to surpass themselves. You are the ones who shape them. You hold all power over them. You owe humanity its heroes. Create them!"

— Valentine de Saint-Point, The Manifesto of Futurist Woman

The Donna Fascista was a distinctive blend of traditional and modern values. She was a mother and homemaker, yet also an active participant in societal and state affairs, encapsulating fascist ideals regarding women. This brand of feminism diverged from liberal feminism, which seeks to disassociate women from motherhood and encourage their involvement in roles traditionally occupied by men. Instead, fascist feminism celebrated motherhood, opposed abortion, and upheld the family unit. Consequently, it diverged from the concept of liberation as seen from a liberal viewpoint. Although it did not achieve the same level of influence as liberal feminism, which together with Marxist feminism shaped the post-war feminist landscape, fascist feminism was nonetheless a notable current within its historical context. It is worth noting that despite contemporary views often critiquing maternalist policies, fascism revered motherhood and maternalism as virtues.

The Italian educational reforms of 1926 under fascist rule were groundbreaking, moving away from longstanding conservative traditions. Article 11 of the state regulation of that year declared that academic competitions and exams were accessible to both men and women, albeit with certain gender-specific limitations. The era also saw an emphasis on women's sports and the establishment of female youth organizations mirroring those for young men. The founding of OMNI in 1925 underscored the regime's commitment to supporting mothers and children, particularly single mothers, and it remained influential until its dissolution in 1975.

In the realm of athletics, Ondina Valla, known endearingly as "Little Wave," made her mark in the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games by winning Italy's first female Olympic gold in the 80m hurdles, even setting a world record in her semi-final. Her extraordinary success made her a symbol of excellence for Italian youth. Moreover, the war years saw a substantial number of women enlisting in the Female Auxiliary Service, taking on a range of crucial roles and demonstrating their active engagement during a tumultuous era.

Italian women military veterans

British Fascism

Sir Oswald Mosley, the head of the British Union of Fascists, regarded himself as a feminist, which was in line with his forward-thinking views. Echoing Mussolini's aversion to strict cultural conservatism, Mosley could be viewed as a progressive individual. Additionally, the British Union of Fascists included a significant number of feminists within its membership.

“Question 31. Would women be eligible as representatives (i) on all Corporations, (ii) on any Corporation?

They will be eligible for all Corporations representing their industry or profession. In addition the great majority of women who are wives and mothers will for the first time be given effective representation by Fascism. A special Corporation will be created for them, which will have special standing in the State. The Corporation will deal with outstanding women's questions such as mother and child welfare. In addition, it will assist the Government in such matters as food prices, housing, education and other subjects, in which the opinion of a practical housewife is often more than that of a Socialist professor or spinster politician.

Question 32. Will the position of women be in any way inferior under Fascism?

Certainly not. Fascism in Britain will maintain the British principle of honouring and elevating the position of women. We certainly combat the decadence of the present system which treats the position of wife and mother as inferior. On the contrary, we consider this to be one of the greatest of human and racial functions to be honored and encouraged. But women will be free to pursue their own vacations. Fascism combats the false values of decadence not by force, but by persuasion and example.”

— Oswald Mosley, Fascism 100 Questions Asked and Answered

Similar to Italian Fascism, British Fascism implemented various progressive reforms for women. It was not a reactionary movement seeking to subordinate women to men or revive outdated social norms. Fascism, by its nature, always looked towards the future.

Norah Elam, in her 1935 essay Fascism, Women, and Democracy published in The Fascist Quarterly, expressed her views on Fascism and found the Mosleyite Fascism to be a modern and forward-thinking movement, providing a welcoming environment. Women constituted 25% of the British Union of Fascists (BUF) membership, held positions of authority and leadership within the party, and several, including Elam, were put forward as candidates for elections in 1936. The drive and dedication of these female members were appreciated and recognized within the movement.

Mosley observed in 1940:

“My movement has been largely built up by the fanaticism of women; they hold ideals with tremendous passion.”

— Oswald Mosley, My Life

In Norah Elam's essay, published in the 1935 edition of The Fascist Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 3, she passionately presents arguments in favor of Fascism as the genuine protector of women's interests and liberty. She also intriguingly suggests that Fascism is the natural progression of the original suffragette movement, drawing parallel points of interest between feminism and Mosleyite Fascism. Elam's essay highlights her fervor and dedication to promoting the compatibility of feminism with the principles of Fascism.

“In this conception of practical citizenship, the women’s struggle resembles closely the new philosophy of Fascism. Indeed, Fascism is the logical, if much grander, conception of the momentous issues raised by the militant women of a generation ago. Nor do the points of resemblance end here. The Women’s movement, like the Fascist movement, was conducted under strict discipline, and cut across all Party allegiance; its supporters were drawn from every class and Party. It appealed to women to forget self-interest; to relinquish petty personal advantages and the privilege of the sheltered few for the benefit of the many; and to stand together against the wrongs and injustices which were inherent in a system so disastrous to the well-being of the race. Like the Fascist movement, too, it chose its Leader, and once having chosen gave to that Leader absolute authority to direct its policy and destiny, displaying a loyalty and a devotion never surpassed in the history of this country. Moreover, like the Fascist movement again, it faced the brutality of the streets; the jeers of its opponents; the misapprehensions of the well-disposed; and the rancour of the politicians. It endured the hatred of the existing Government, and finally the loneliness of the prison cell and the horror of forcible feeding. Its speakers standing in the open spaces and at the street corners were denied the right of free speech; its champions selling their literature spat upon and reviled; its deputations were manhandled. Suffragettes became the sport of any rowdy who cared to take the law into his own hands. To make the analogy the more exact, no calumny was too vile and no slander too base to set about the moral character of its leaders, or the aims and objects of the women who owed them allegiance.”

— Norah Elam, The Feminine Contribution to Fascism

Anne Brock-Griggs, an influential feminist and early member of the BUF, joined the movement partly due to her disillusionment with establishment conservatism. She gained recognition through her powerful speeches and was appointed as the Woman's Propaganda Officer within the BUF staff in 1935. Later, she was promoted to the position of Chief Woman's Officer, becoming the national leader of the Women's Division within the party. Brock-Griggs represented the views of female members through the Woman's Page of the party newspaper, Action. In 1937, she ran as a BUF candidate for Limehouse, East London, although her campaign was ultimately unsuccessful. She actively participated in the Peace Campaign, opposing the entry of the United Kingdom into World War II.

During her time with the BUF, Brock-Griggs published a pamphlet in 1936 titled Women and Fascism: Ten Points of Fascist Policy For Women. This pamphlet reflected the official stance of the BUF on women's issues, approved by Mosley himself. The writing strongly emphasized welfare and social reform, with the aim of benefiting women.

These benefits briefly summed up were:

Women having representation in parliament

Legalistic equality for women

Equal pay for equal work

The right to work and vote

Improvement of working conditions for women

Removal of all sexual discrimination

Support for health and maternal infant welfare

Affordable housing for families

Free nursery schooling and free higher education

An affordable food supply for families

Despite facing challenges due to ill health, Brock-Griggs continued her involvement in politics, joining Mosley's post-war Union Movement after her release from detention under Defence Regulation 18B during the war. Unfortunately, she passed away from cancer in the 1960s. Female members of the BUF actively participated in various roles within the organization, including security positions. They also took part in self-defense courses to enhance their skills. It is worth noting that women from different organizations affiliated with the BUF were trained in jiu-jitsu, demonstrating their commitment to personal defense and preparedness.

The Fascist Weekly reported:

“No male member of the BUF is permitted to use force upon any woman, and women Reds often form a highly noisy and razor-carrying section at Fascist meetings. Thus we counter women with women.”

— A. K. Chesterton, The Fascist Attitude to Women

In her book Feminine Fascism: Women in Britain's Fascist Movement, Julie V. Gottlieb delves into the fascinating lives of notable figures within the British fascist movement. Mary Raleigh Richardson was a prominent figure in the suffragette movement, most infamous for her attack on the Rokeby Venus painting during a 1914 Votes for Women demonstration. Richardson's fervor for the suffrage cause led her to engage in more radical actions such as arson, damaging the Home Office, and bombing a railway station. In the 1930s, Richardson, along with her acquaintance Mary Sophia Allen, who was influenced by Hitler, became a part of Sir Oswald Mosley's Blackshirts. Allen had a deep interest in the operations of fascist governments and traveled extensively through Europe to study and take insights from these political systems. Her passion mirrored that of Margaret Damer Dawson; the two shared a complex and deep relationship, living together in London from 1914 to 1920 and maintaining both a personal and professional partnership.

Before aligning with the fascist movement, both Allen and Dawson were engaged with Emmeline Pankhurst's Women's Social and Political Union. Remarkably, Allen and her partner Margaret were instrumental in founding the first contingent of female police officers in Britain. Their efforts in advancing women's rights and engaging in social activism reflected their strong dedication to the cause.

Allen said this about the BUF:

“I was first attracted to the Blackshirts, because I saw in them the courage, the action, the loyalty, the gift of service, the ability to serve which I had known in the suffragette movement.”

— Mary Allen to the Daily Mail 1934

During her travels throughout Europe, Mary Sophia Allen forged relationships with key fascist figures, such as Eoin O'Duffy in Ireland and Benito Mussolini in Italy. Her journey in 1934 included a notable meeting with Adolf Hitler, where they discussed the role of women in policing. This interaction with Hitler significantly influenced Allen, inspiring her to publicly voice her admiration for the Führer. Though her association with Oswald Mosley's BUF didn't become official until 1939, Allen was actively engaged in the movement's militant operations. In 1933, she was instrumental in forming the Women's Reserve, an organization designed to support the nation against the threat of insurgent elements. Upon becoming a formal member of the BUF, Allen turned to journalism, writing extensively for the party's publications and unreservedly embracing her identity as a committed Fascist.

Julie V. Gottlieb, has argued that:

“Allen was a prominent supporter of Mosley's British Union, a movement she claimed she had joined due to her sympathy for its anti-war policy."

— Julie V. Gottlieb, Feminine Fascism

One lesser-known female figure within the context of British Fascism is Rotha Beryl Lintorn-Orman. Lintorn-Orman had notable experience as a veteran of the Women's Emergency Corps and the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Services during the years 1914 to 1918. In 1918, she assumed leadership of the British Red Cross Motor School, a vital institution that trained drivers to support the battlefield efforts. Following the conclusion of World War I, Lintorn-Orman established the British Fascisti in 1923. This organization holds the distinction of being the first openly Fascist group in Britain, with a unique aspect being its female leadership. Julie V. Gottlieb suggests that the creation of the British Fascisti can be seen as a feminist response to the Primrose League. Lintorn-Orman's political inclinations leaned more towards Tory Conservatism, but her strong anti-communist sentiments and admiration for Benito Mussolini's action-oriented style of politics propelled her towards Fascism. It is important to note, however, that her alignment with Fascism was not driven by a deep ideological commitment to the movement. Nonetheless, Lintorn-Orman's support for feminism set her apart within the context of British Fascism.

Quoting from Feminine Fascism:

“Not only was Lintorn-Orman a single woman, but her preference for women in uniform and the paramilitary regimentation of the feminine provoked the pejorative description of her as a ‘mannish-woman'.”

— Julie V. Gottlieb, Feminine Fascism

Lintorn-Orman's inclination towards the presence of women in uniform can be interpreted through the lens of masculine inclinations, lesbian eroticism, and a broader enthusiasm for patriotic conformity. However, as her movement gradually disintegrated, she receded into relative obscurity. Lintorn-Orman's descent into addiction, particularly to drugs, lesbianism, and alcohol, compounded by her politics, it contributed to her marginalization to genuine Fascist organizations such as Oswald Mosley's BUF.

German National Socialism

Within the German context, particularly during the ascent of National Socialism, there exists an often-overlooked aspect of feminist movements. Contrary to the belief of some National Socialists who viewed feminism as incompatible with their ideology, being Jewish or unfavorable, the Nazi movement actually attracted significant female support. In the presidential elections of March 1932, around 26.5% of German women voted for Hitler. Moreover, during the elections of September 1931, women contributed nearly half of the total 6.5 million votes received by the Nazi party, with about 3 million votes cast by women.

The Frauenwerk, a state-endorsed organization for women's activities, boasted over 4 million female participants. The women’s division of the German Labor Front also had a membership of 5 million women. The Nazi government fostered the growth of such organizations to rally women throughout the various sectors of the Reich and to encourage a rebirth of traditional femininity. Within this framework of Nazi feminism, Sophie Rogge-Börner, an educator and author, stood out as a key advocate. Rogge-Börner and her peers in the feminist faction of the NSDAP envisioned their feminism through the lens of a glorified, semi-legendary Nordic Golden Age, where sexual equality was the norm. They contended that genuine national unity, predicated on social harmony and class solidarity, would remain elusive as long as the state persisted in gender-based discrimination.

Sophie Rogge-Börner, though never an official member of the NSDAP, was actively involved with various German völkisch (nationalistic) groups, such as the National Socialist Freedom Movement. Her commitment to National Socialism was evident, as she participated in the völkisch literary movement. Like many German nationalists at the time, she welcomed Hitler's 1933 government with great optimism. After Hitler's ascension to power, Sophie compiled a memorandum that was later featured as the leading article in the inaugural issue of the National Socialist publication, The German Female Fighter. Later, her work, along with multiple similar articles on Nazi feminism, was compiled into the 1933 book titled German Women Address to Adolf Hitler. The Prussian Reich Commissioner Göring offered a short written recognition for this publication.

Although the government ultimately prohibited the book in 1937, it did instigate some modest reforms. These changes were largely centered around women's groups, support for mothers, cost-effective housing, and additional policies that favored families and motherhood, echoing measures taken under Italian Fascism and the BUF.

Quoting from the memorandum:

“In all other areas of civic life the necessity of bringing in the foremost influence of women applies just as much. This claim to a greater area of responsibility cannot be dismissed as feminism. The Volk have an inalienable right to leadership by the best Germans of both sexes. The Volk comprises the entirety of the people; if it is to prosper it can therefore only be led through the whole of the people. The best men and the best women have to share in the leadership of the nation. Men and women must participate in every leadership office.”

— Sophie Rogge-Börner, German Women Address to Adolf Hitler

Rogge-Börner was of the conviction that the quest for gender equality was deeply intertwined with anti-Semitic sentiments and ideals of Nordic aesthetic perfection. She asserted that the Germanic peoples had a historical legacy of gender parity, where women were afforded full equality and the space to realize their full potential. Along with other Nazi feminists, Rogge-Börner championed the notion that women had the capacity to serve as priestesses, leaders, and warriors, referencing texts like the Edda, Icelandic sagas, the Hervarar saga, Gesta Danorum, and Tacitus's accounts to bolster their vision of a Nordic brand of feminism.

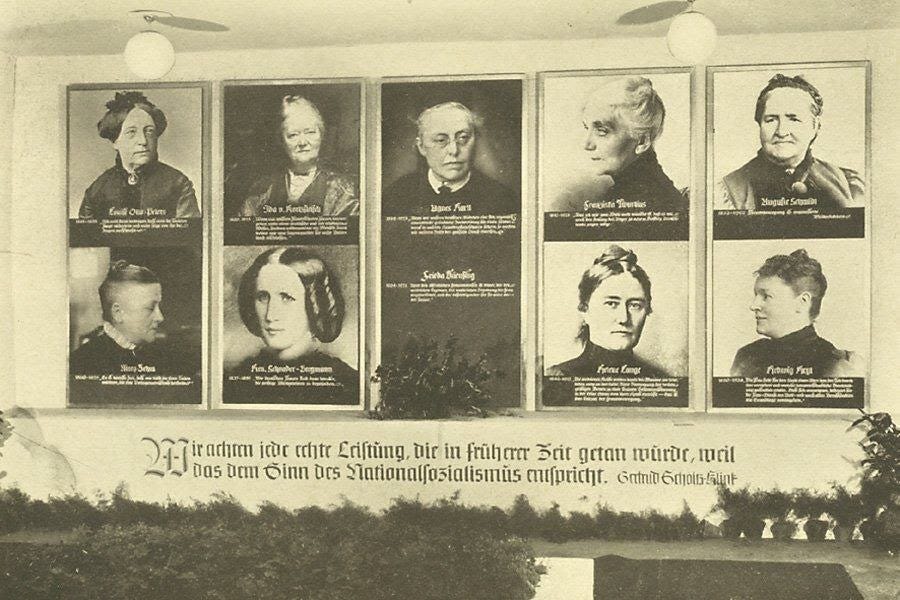

Leveraging the National Socialist ideology that exalted Germanic identity as the pinnacle of cultural achievement, these feminists argued for a revival of the Nordic golden age in contemporary Germany, laying the groundwork for what is known as völkcish feminism. Despite the fact that Rogge-Börner's ideals of complete gender equality did not come to fruition under Hitler's rule, her allegiance to National Socialism remained steadfast through World War II and persisted until her death. Remarkably, the National Socialists also recognized various feminists, including Hedwig Heyl, Auguste Schmidt, and Helene Lange, in a mural that celebrated their historical contributions, illustrating a complex and often contradictory relationship with feminist thought.

“We respect all genuine achievements made in earlier times, because they correspond to the spirit of National Socialism.”

— Adolf Hitler, The Path of Women mural

The National Socialist mural showing various feminists

In 1926, Emma Hadlich, a feminist, ignited a debate with an article in the National Observer, the official newspaper of the NSDAP. In her piece, Hadlich criticized Elsbeth Zander, the head of the women's organization affiliated with the NSDAP. This led to a series of charges and countercharges published in the newspaper from January to April 1926. Many of the issues raised during this debate resurfaced in 1933 with the publication of German Women Address to Adolf Hitler.

Despite the National Socialists' rise to power, Nazi feminists did not cease expressing their beliefs. They held that women, distinct from men but equally capable and intelligent, had much to offer the German populace beyond their roles as mothers. In their envisioned German society, women would stand shoulder to shoulder with men, contributing to the communal welfare. These feminists drew on anthropological theories suggesting that matriarchal societies were humanity's earliest social structures and claimed that in ancient Germanic cultures, men and women were of equal standing. The core of the debate between Nazi feminists and their critics centered on the historical realities of Germanic society rather than aspirations for the future.

While many of these feminist arguments were compatible with National Socialist thinking, Irmgard Reichenau pushed beyond traditional boundaries, echoing sentiments found in radical modern liberal feminism. In her March 1932 essay to Hitler titled Gifted Women, Reichenau contended that women deserved influential roles not just for societal advancement but for their own self-realization. She defended professional women against criticism that they exacerbated unemployment or chose to remain childless, and she challenged the idea that they lacked maternal instincts. Reichenau criticized men for preferring comfortable marriages over partnerships with strong, intelligent women, arguing that career-oriented women could be superior mothers compared to those focused solely on motherhood, citing historical figures like Maria Theresa and Clara Schumann as examples. She cautioned that unutilized female talents could manifest negatively, resulting in hysteria, neurosis, or domestic despotism.

The debate's remarkable aspect was its fluidity in doctrinal terms. Alfred Rosenberg recognized the diversity of perspectives within Nazi feminism through Hadlich's original article and Zander's counterargument, suggesting open discussions about these differences. Other commentators pointed out that this internal conflict showcased the movement's dynamism. Rosenberg ultimately deferred to the party leadership, underscoring that any divergences should be subordinated to the overarching fight against Capitalism, Marxism, and Jews.

In 1933, when these feminist issues resurfaced, Irmgard prefaced her book with quotes from Hitler, calling on anyone who perceived danger to the people to openly combat evil, and the other stating that "He who loves Germany may criticize us." In the National Observer, Rosenberg clarified that his critique of Hadlich's work didn't imply female inferiority but rather emphasized differences in psyche and biology. Despite Rosenberg's attempt to settle the discussion in print, Nazi feminists persisted in their opposition to his stance. Irmgard even accused him of harboring Jewish tendencies due to his sexist views. As a result, many feminists within the National Socialist fold were subject to censorship by the German government.

For more information on Nazi feminists, one can refer to the book Mobilizing Woman For War by Leila J. Rupp. The book illustrates that within the Third Reich, women occupied a wide array of roles. They were integral to women's administrative bodies, played roles in female educational development, and held positions as academics and researchers. Women also served in public safety sectors such as the police and fire departments, as well as in transportation, concentration camps, clerical work, support roles within the military, and the medical field as nurses, physicians, and military healthcare managers. Their involvement extended to the political arena and the realm of aviation. A number of women were recipients of distinguished honors, including the Iron Cross and the Golden Party Badge. Notably, the German Luftwaffe was among the pioneers in employing women as pilots.

A video on Hanna Reitsch

In 1944, a substantial contingent of women assumed roles as combat pilots to free up their male counterparts for frontline service, and hundreds more served as instructors in gliding. Hanna Reitsch, a celebrated test pilot decorated with multiple accolades, was among these women. In 1945, she engaged directly in combat operations by undertaking the final flight mission into and subsequently out of besieged Berlin.

After the war in her last interview she said this:

“And what have we now in Germany? A country of bankers and car-makers. Even our great army has gone soft. Soldiers wear beards and question orders. I am not ashamed to say I believed in National Socialism. I still wear the Iron Cross with diamonds Hitler gave me. But today in all of Germany you can't find a single person who voted Adolf Hitler into power. Many Germans feel guilty about the war. But they don't explain the real guilt we share – that we lost.”

— Hanna Reitsch, interview with Ron Laytner

Violette Morris was born into a military family in Paris, Morris began her sporting endeavors in a Belgian convent, where nuns introduced her to a variety of sports including cricket, basketball, cycling, and hockey. After the monastery, she turned her focus to English boxing and secured a commendable fifth place in the French deep-sea swimming championship in 1913. Following the death of her parents in 1917, Morris immersed herself in the world of sports, joining the French Women's Sports Federation and the Olympique Football Association.

Morris excelled in a diversity of disciplines, including shot put, javelin, football, swimming, cycling, athletics, discus throwing, weightlifting, motorcycling, and motoring. Her accolades are numerous, notably being crowned the best 5km cyclist in 1925 and winning the Dolomites rally in 1934, as well as clinching the French football championship in 1920, 1925, and 1926. Despite her sporting prowess, Morris's career was marred by controversy, including allegations of doping and scandal surrounding her personal style. These controversies, along with underlying sexism in the sports community, may have contributed to her estrangement from French sports and subsequent pivot towards radical ideologies. Morris's association with French fascism and her personal choices led to a profound departure from the conservative cultural norms of her time.

Violette Morris in a car

After being banned from competitive sports due to the scandals, Adolf Hitler personally invited Morris to attend the 1936 Berlin Summer Olympics as a guest of honor, disregarding her gender nonconformity, bisexuality, and her choice to undergo a mastectomy in 1926 to better fit into racing cars. With the warm reception in Berlin came an offer for cooperation, leading Morris to become an integral figure in Vichy France, dubbed the “Hyena of the Gestapo.” She took on roles as a spy, confronting British intelligence networks, interrogating women for the French Gestapo, and managing operations at the Luftwaffe garage in Paris. Morris's active involvement with the Nazi occupation and Vichy France's government underscores her complicity and collaboration with these regimes.

The true extent of Morris's ideological alignment with the fascist and Nazi causes is still subject to historical debate. While some argue her collaboration stemmed from opportunism or necessity, others contend it indicated a deeper resonance with the principles of fascism. Morris's life ended violently in 1944, when she was ambushed and killed by the French Resistance. The intensity of the attack left her and the others in her car, including a married couple and their two children, along with a mutual friend, unrecognizable. She was hastily buried in an unmarked grave. In death, efforts to demonize her intensified, with enemies casting her as a sadistic figure — a portrayal that has contributed to her vilified status in historical memory.

Eleanor Bauer played a crucial role in the early formation of the NSDAP, offering substantial support to Adolf Hitler from the party's inception. Her experience as a World War I nurse and her involvement with the Freikorps Oberland, a paramilitary unit engaged in conflicts against the Bavarian Soviet Republic and in the Baltics in 1919, laid the groundwork for her entry into Nationalist politics. Bauer's unwavering commitment to the Nazi cause became evident when she was arrested on March 11, 1920, for delivering an inflammatory anti-Semitic speech at a women's assembly in Munich. Her subsequent acquittal not only absolved her of charges but also solidified her status as a martyr within the Nazi movement. Bauer sustained injuries during the Beer Hall Putsch, positioning her as the sole woman actively engaged in the failed coup and earning her the prestigious Blood Order medal, an exclusive accolade granted to only 16 women within the Nazi Party.

As a trusted confidante of Hitler, Bauer held a significant position in his inner circle. Heinrich Himmler appointed her to a high-ranking role as the welfare sister for the Waffen-SS, a responsibility equivalent to an SS Oberführer, akin to a general in the Waffen SS hierarchy. In 1934, Bauer established the National Socialist Order of Sisters with a focus on nursing, assuming the role of honorary chairwoman by 1937. Her dedicated service to the party was further recognized through the receipt of the golden party badge. Bauer garnered acclaim during the Nazi era as the epitome of the Nazi woman, with Der Spiegel labeling her "the nurse of the Nazi nation," a testament to her prominent status. Among her numerous decorations were the Silesian Eagle Order, the Silver Medal for Bravery, and the Baltikum Cross. Notably, Bauer's steadfast allegiance to National Socialism persisted even after the collapse of the Nazi regime, underscoring her enduring loyalty and resolute belief in the principles she ardently upheld.

Conclusions

In exploring the historical connections between feminism and fascism, it's clear that these political movements aren't simply oppressive or rooted in reactionary thought. Fascist policies often embraced modernism, differing from traditionalism like those of Joseph de Maistre. It's important to correct the misconceptions spread by some who claim to support fascism yet embody outdated misogynistic stereotypes.

These movements aimed for an inclusive society, promoting collaboration across class and gender, and sought to enhance national well-being. Any deviation from this inclusive and progressive vision misrepresents true fascist ideology, which did not confine women to domestic roles or oppose contemporary societal dynamics. Fascist feminism endeavored to uphold traditional family roles while ensuring women's representation within a corporatist system, successfully rallying women from diverse backgrounds.

While the legitimacy of fascist feminism is debated, some modern feminists, anti-fascist activists, and even factions within fascism acknowledge its pro-women elements. Mainstream academics often downplay these aspects to fit a particular narrative. A fascist movement advocating for women's empowerment challenges Left-wing assumptions and fosters national unity. Although not all arguments here need endorsement, it's evident that a pro-women stance can coexist with fascist thought.