Introduction

George Fitzhugh was a lawyer, artist, and political philosopher hailing from Virginia, who left a mark on the field of sociology. Originating from Prince William County and growing up in King George County, he set up his law practice in Port Royal, Virginia, before eventually taking a position in the Confederate Treasury Department. Fitzhugh was deeply familiar with the abolitionist writings of his era. His publications, notably Sociology for The South and Cannibals All! Or, Slaves Without Masters, sparked significant reactions with their potent defenses of slavery. Interestingly, Fitzhugh was also driven by a desire to maintain domestic tranquility, which led to his appointment as a judge in the Freedman's Bureau. In this capacity, he aided newly emancipated slaves in integrating into post-Civil War Southern society. Fitzhugh retired from writing in 1872. Following his wife's death in 1877, he relocated to Frankfort, Kentucky, to reside with one of his sons. In 1880, he moved again to Huntsville, Texas, to live with a daughter. By that time nearly blind, Fitzhugh passed away in Huntsville on July 30, 1881, and was laid to rest in Oakwood Cemetery. This article will delve into his political views in depth.

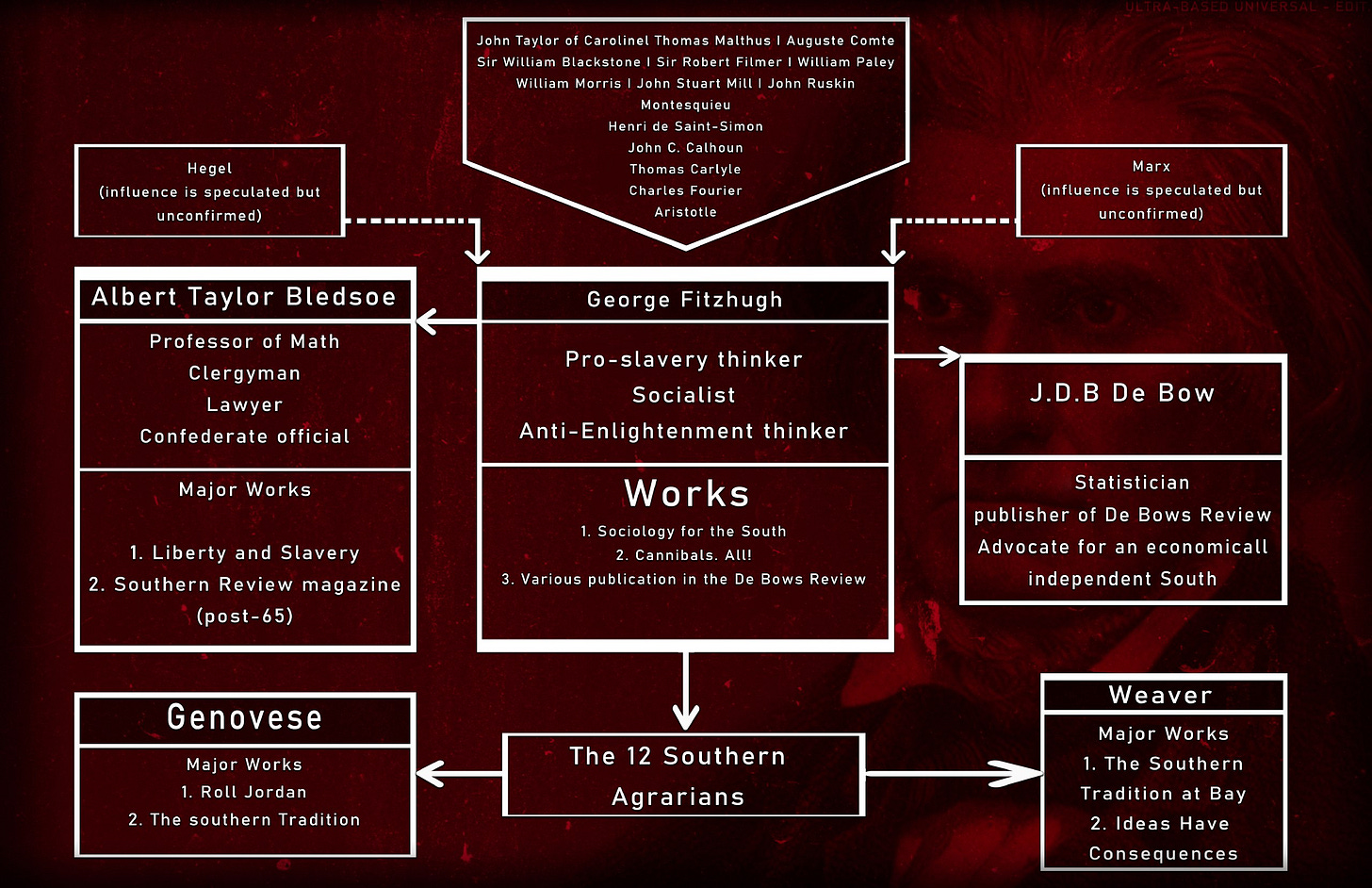

A short video explaining his views

Slavery As Socialism

Fitzhugh was deeply interested in the emerging labor issues that were gaining prominence in the political dialogues in Europe and the United States. Like many others, he saw socialism as the answer to these labor concerns. For him, slavery represented the most tested and reliable form of socialism. Fitzhugh underscored this point by stating, "Slavery is a form, and the very best form, of socialism." According to Fitzhugh, the notions of "freedom" and "slavery" are relative and can assume various meanings depending on the context and the larger framework in which they are used. He emphasized that this larger framework recognizes that all humans have certain needs, including sustenance, security, and community, which are crucial for survival. Beyond survival, there are also civilizational needs related to self-actualization and fulfillment. Fitzhugh identified only one distinction between the indentured servitude in laissez-faire capitalism and the explicit slavery in socialism: in the latter, all these needs are constantly fulfilled and guaranteed holistically, while in the former, these needs could be lost at any time since the "insecurities of freedom" favored the privileged over the disadvantaged, due to the unregulated accumulation of multigenerational capital that inherently encourages exploitation.

Fitzhugh advanced the notion that the prevailing "White race" in America, specifically alluding to the governing Anglo-Saxon and Jewish elites, held monetary influence and exercised their domination over “Colored” individuals. Fitzhugh argued that the “Colored”, especially “the Negroes” (or Black individuals), were entitled to a more dignified treatment rather than being subjected to the exploitation brought about under laissez-faire capitalism. In his view, capitalism obstructed their access to the economic and social safeguards provided by the system of slavery. Fitzhugh asserted that if Black individuals were permitted to compete freely in society, they would be eclipsed or outmaneuvered and thus ultimately confronted with certain and perpetual poverty and misery.

Fitzhugh speculated that even fervent abolitionists would acknowledge the perceived inferiority of Black individuals in terms of their habits and aptitude for wealth accumulation relative to Whites. He advanced this perceived shortcoming as a justification for subjugating Black individuals should they continue to reside in America. Reflecting on the conditions of contemporary American ghettos, one could posit that Fitzhugh's viewpoint bears some relevance. He underscored a significant concern regarding the potential economic disadvantages encountered by Black individuals within a White-dominated society.

“The negro is improvident; will not lay up in summer for the wants of winter; will not accumulate in youth for the exigencies of age. He would become an insufferable burden to society. Society has the right to prevent this, and can only do so by subjecting him to domestic slavery.“

“In the last place, the negro race is inferior to the white race, and living in their midst, they would be far outstripped or outwitted in the chase of free competition.”

— George Fitzhuge, Sociology For The South

In Cannibals All! Or, Slaves Without Masters published in 1856, George Fitzhugh posited that the writings of socialists offer the most authentic defense of slavery. Despite his profound regard for Aristotle's justification of slavery, he was of the opinion that modern socialists, including individualistic ones like Stephen Pearl Andrews, provided valuable perspectives on "the sovereignty of the individual." Fitzhugh frequently quoted Andrews, whom he deemed the most adept American writer on moral science, even though Andrews, an abolitionist, held a somewhat positive outlook on slavery. The rationale behind Fitzhugh's respect becomes apparent when Andrews's methodology is scrutinized. Andrews identified slavery as not merely forced labor, but the apex of labor exploitation, including milder forms of slavery present in free, commercial societies. Andrews contended that the moment someone seizes another's services without offering an equivalent, they start to enslave that person, resulting in varying levels of subjugation and degradation.

From a Marxist standpoint (the labor theory of value), Andrews believed that labor should underpin exchange in commercial transactions. He viewed capital as devoid of inherent productive power, considering it merely as “pooled labor”. Thus, capitalists who profited from rent, interest, and other forms of capital investment were essentially exploiting the labor of the actual producers. Fitzhugh concurred with this view, appreciating the socialists' incisive critique of the capital-labor strife. However, he pointed out that socialists often failed to offer viable solutions. Some established "utopian" communities to tackle the issue, while others foresaw the emergence of an ideal society after its major sins were eradicated. Unlike the majority of unsuccessful utopian social experiments, Fitzhugh argued against applying a socialist economic system based on the "cost principle" universally, as suggested by most socialists, foreseeing disastrous outcomes.

Fitzhugh accepted the inevitable capital-labor conflict in all societies. For Fitzhugh the optimal solution was to abolish capitalism and according to him, slavery, with a history spanning thousands of years, was the most effective solution. Fitzhugh deviated from conventional defenders of slavery who typically argued from a moral perspective. He argued that slavery's defenders need not justify it morally, as Northern states were equally complicit in labor exploitation. Fitzhugh insisted that the pivotal question was which system, slavery or so-called "free" labor, yielded better results. Fitzhugh asserted that the North had not yet fully experienced the repercussions of wage-slavery due to the abundance of land in the West, which provided an escape for disgruntled laborers. However, Fitzhugh forecasted that with the West's population growth and the adverse consequences of a so-called “free society” — such as infidelity, labor riots, and poverty — would become rampant.

“Property is not a natural and divine, but conventional right; it is the mere creature of society and law… if private property generally were so used to injure, instead of promote public good, then society might and ought to destroy the whole institution.“

“Free trade or political economy is the science of free society, and socialism is the science of slavery.”

“The capitalist cheapens their wages; they compete with and underbid each other, for employed they must be on any terms. This war of the rich with the poor and the poor with one another, is the morality which political economy inculcates.“

— George Fitzhugh, Sociology For The South

In a public discourse with abolitionist A. Hogeboom in 1857, Fitzhugh issued a challenge, stating he would acquiesce to the abolition of slavery only if it could be proven that the majority of people would benefit materially from it. He argued that a significant portion of the population, perhaps as much as 90% or even 95%, would fare better under strict governance and disciplinary measures. Fitzhugh maintained that these individuals required authority figures not only for regulation but also for their protection and livelihood. Although Fitzhugh did hold racial prejudices towards Black people, his defense of slavery wasn't strictly based on a racial bias. He reasoned that White laborers in the North, who were in effect slaves without masters, lived in worse conditions than their Southern counterparts, who were slaves under masters. Therefore, he argued that even White laborers would thrive under the moral structure of "universal and comprehensive slavery". In Fitzhugh's view, true freedom was synonymous with being content and well-cared for, and since only slavery could best ensure this, being a slave was essentially equivalent to being free; conversely, to be free was to be a slave.

Fitzhugh depicted slave plantations as Utopian Socialist communities, where slaves were provided with food, shelter, and medical care throughout their lives, irrespective of their physical condition—a level of care he claimed was not extended to Northern workers. While abolitionists circulated accounts of slave cruelty, Fitzhugh maintained that these were outliers and that most slave owners treated their slaves humanely. A devout Christian, Fitzhugh contended that a laissez-faire society replaced Christian virtues with selfishness, leading to harmful competition. He advocated for extending familial relationships to society through slavery, which he saw as a protective mechanism for the vulnerable and a means to foster selfless relationships. He put forth the image of masters as altruistic caretakers, in stark contrast to the uncaring capitalist system. Fitzhugh asserted that all discerning reformers recognize the necessity of slavery and seek to abolish free competition.

“Socialism proposes to do away with free competition; to afford protection and support at all times to the laboring class; to bring about, at least, a qualified community of property, and to associated labor. All these purposes, slavery fully and perfectly attains.“

— George Fitzhugh, Sociology For The South

Fitzhugh emphasized that everyone relies on the labor of others for their survival. However, he argued that slavery reduced the exploitation of laborers. Contradicting the common belief that goods produced by free labor were cheaper than those produced by slave labor, Fitzhugh maintained that slavery allocated a larger share of a slave's labor products to the slave compared to the wage system. He credited this to the master's guarantee, while capitalist employers only paid the minimum necessary to employ workers. Hence, Fitzhugh claimed these "mini-islands" of slavery in the South were fairer to workers than Northern factories. Fitzhugh held the view that slavery had advantages over free labor. Slavery not only fostered closer human relationships, as advocated by socialists, but also merged labor and capital, enhancing their productivity.

Slavery aligned with communism in providing individuals with what they needed, rather than what they earned through labor. Furthermore, Fitzhugh suggested that slave owners, driven by both familial affection and self-interest, took good care of their slaves since slaves were both valuable property and dependent beings. This contrasted with the ongoing strife between free laborers and their employers, who sought higher wages amid intense competition for employment. Fitzhugh claimed free laborers were worse off and treated more poorly than animals on English farms, while slaves received better treatment.

“Our slaves till the land, do the coarse and hard labor on our roads and canals, sweep our streets, cook our food, brush our boots, wait on our tables, hold our horses, do all hard work, and fill all menial offices. Your freemen at the North do the same work and fill the same offices. The only difference is, we love our slaves, and we are ready to defend, assist and protect them; you hate and fear your white servants, and never fail, as a moral duty, to screw down their wages to the lowest, and to starve their families, if possible, as evidence of your thrift, economy and management—the only English and Yankee virtues.“

— George Fitzhugh, Cannibals All! Or, Slaves Without Masters

In his other book Sociology For The South, Fitzhugh posits that the seamless orchestration of labor in a communist society necessitates that individuals forfeit their autonomy, surrendering to the state's authority, a condition he likens to slavery. He contends that socialism is progressively aligning with this trajectory, positing that laissez-faire economics epitomize a liberal society, whereas socialism is a euphemism for slavery and familiar communality. Fitzhugh suggests that socialist reformers, notwithstanding their opposition to unregulated competition, endorse a variant of slavery under a different guise.

Fitzhugh further criticizes numerous socialists for their idealistic interpretation of human nature. He underscores that socialist societies necessitate strong leadership to flourish, analogous to traditional familial hierarchies. He observes that even Proudhon, a prominent anarchist and socialist thinker, acknowledged the potential for socialism to evolve into explicit slavery. As a result, Fitzhugh implores socialists to revise their stance, promoting a resurgence of domestic slavery, a variant of socialism he deems superior. He further argues that while nascent socialist trends pledge enhanced results, they acknowledge the necessity to suppress mankind's innate nature to realize this.

“All concur that free society is a failure. We slaveholders say you must recur to domestic slavery, the oldest, the best and most common form of Socialism. The new schools of Socialism promise something better, but admit, to obtain that something, they must first destroy and eradicate man’s human nature.“

— George Fitzhugh, Sociology For The South

Deeply influenced by Thomas Carlyle, Fitzhugh shared Carlyle's disdain for economics, labeling it the "dismal science" due to its association with the abolitionist movement. Interestingly, these thinkers, known for their pro-slavery stance, found common ground in socialism to combat their shared adversary, laissez-faire economics. In his analysis, Fitzhugh argues that the institution of slavery contradicts the principles of capitalism. He derides free markets, examining them in the context of labor revolts in Europe and societal instability, which he attributes to laissez-faire economic principles. However, it's crucial to clarify that Fitzhugh was not against industrial and technological progress. Far from being a technophobe, he advocated for a more gradual and thoughtful approach to industrial development that wouldn't compromise societal integrity for the sake of boosting economic output. He prioritized the overall well-being of society over any short-term material benefits.

Fitzhugh saw the Prussian military as the pinnacle of honor and distinction, an idea based on its noble leadership who held control over the nation's people and land. He extolled Frederick The Great, the Prussian hierarchy, and it’s militarism. Fitzhugh asserted that individual worth only materialized when contributing to the common good, an idea he compared to a bee's function in a hive, an analogy he regularly employed. In his view, individuals could only achieve their utmost through communal efforts. Fitzhugh's rejection of liberalism was deeply rooted in his denial of basic human rights and his disregard for the rights of the slave-owning class. He refined his vision of a autocratic government that would socialize the means of production, drawing on Prussian Cameralism.

Fitzhugh advocated for rigorous economic planning, oversight of citizens' lives, and efficient administration of government affairs, similar to the Prussian model. He acknowledged the benefits of a well-ordered society as portrayed by Carlyle, and pondered how such a model could be replicated in the South. This viewpoint becomes more evident in his discussions on Thomas Hobbes. Fitzhugh tied Carlyle's critiques of liberal societies to the teachings of Hobbes. He frequently used Carlyle's name to strengthen his opposition to liberalism. He praised Hobbes as a thinker who, like Carlyle, discerned the shortcomings of “free societies.” Historically, Hobbes' theories were used to justify autocracy as a means to preserve social peace. Similarly, Fitzhugh viewed Hobbes as the authoritative figure that could prevent the South from the North's looming threat. He embraced Hobbes' rejection of individual sovereignty in favor of absolute rule.

Fitzhugh used the suffering of the poor proletariat class in France to support his views, suggesting a preference among the general population for servitude over the unpredictability of freedom and competitive business. He blamed the downfall of the Paris Commune on the lack of strong, centralized control. If Fitzhugh had lived another hundred years, he likely would have been fascinated and influenced by the progress achieved in Imperial Germany under Otto von Bismarck, Fascist Italy under Benito Mussolini, National Socialist Germany under Adolf Hitler, the Soviet Union under Vladimir Lenin, and even Imperial Japan under Prince Fumimaro Konoe. However, even in his own time, there were figures who shared similar ideologies to those mentioned above, whom Fitzhugh regarded as excellent implementers of his own beliefs and ideas. Fitzhugh praised Napoleon's rise to power, hailing him as a State Socialist. He commended Napoleon's wealth redistribution strategies, which leveraged the wealth of the bourgeoisie to provide for everyone and arranged housing and childcare for the proletariat class. He analogizes these initiatives to the guardianship extended to slaves in the American South.

“With thinking men, the question can never arise, who ought to be free? Because no one ought to be free. All government is slavery.“

— George Fitzhuge, Sociology For The South

Fitzhugh rejected the very foundations of the American Revolution, challenging the principle of the "consent of the governed.” He posited that state power does not emanate from the governed's consent, emphasizing that the marginalized - women, children, non-property holders, and Blacks - did not consent to the Revolution or the resultant governments. Fitzhugh asserted that governments are born and sustained by force, essentially forming a self-imposed despotism. This critique drew substantial attention, especially among abolitionist ranks, and is even said to have angered Abraham Lincoln. In response to Thomas Jefferson and John Locke "natural rights" notion, Fitzhugh rejected that all men inherently possess such rights, claiming that such rights would contradict God’s divine design. He inferred that the societal hierarchy is a natural order, where the majority are destined to be protected, implying an inherent slavery. In this, only a select few are naturally predisposed to command, thus having a right to mastery. For Fitzhugh, liberty is an evil which government is intended to correct.

“We must combat the doctrines of natural liberty and human equality, and the social contract as taught by Locke and the American sages of 1776. Under the spell of Locke and the Enlightenment Jefferson and other misguided patriots ruined the splendid political edifice they erected by espousing dangerous abstractions — the crazy notions of liberty and equality that they wrote into the Declaration of Independence and the Virginia Bill of Rights. No wonder the abolitionists loved to quote the Declaration of Independence! Its precepts are wholly at war with slavery and equally at war with all government, all subordination, all order. It is full if mendacity and error. Consider its verbose, newborn, false and unmeaning preamble. There is no such thing as inalienable rights. Life and liberty are not inalienable. Jefferson was the architect of ruin, the inaugurator of anarchy. As his Declaration of Independence stands… it is exuberantly false, and absurdly fallacious.”

— George Fitzhugh quoted in The Approaching Fury: Voices of the Storm 1820-1861 by Stephen B. Oates

In countries where property was held by a select few, Fitzhugh proposed that enslaving the weak was the optimal form of communism. He believed that philanthropic individuals, wishing to control their beneficiaries, should invest in slaves since the greater the control, the greater the capacity to do good. Fitzhugh recommended that poor Whites in the North should be handed over to capital owners, underscoring the need for more protection and control. He argued that the masses could not be governed solely by law and moral persuasion, but required aristocratic discretion.

Fitzhugh argued that in a competitive economy, only a small minority would have the capability to excel, leaving the majority susceptible to exploitation. He believed that this majority warranted protection, which necessitated their control. Slavery, in his view, offered both protection and control. He asserted that to safeguard individuals, they must first be enslaved. Joseph Dorfman encapsulated Fitzhugh's stance by stating that the conservative principle affirmed society's obligation to protect the weak.

"Slavery is a form of communism… The manner to which the change shall be made from the present form of society to that system of communism which we propose is very simple."

— George Fitzhugh, Cannibals All! Or, Slaves Without Masters

Fitzhugh suggested that the continued existence of slavery was a remnant of pre-Liberal societal structures. He advocated for the expansion of slavery as a way to revert to a feudal society, thereby mitigating the perceived damage caused by the Liberal Enlightenment and laissez-fair capitalism. Fitzhugh attributed the wealth and advanced civilization of historical societies such as Greece, Rome, Egypt, and Judea to slavery, highlighting their remarkable achievements in fine arts, governance, and philosophy, despite their limited understanding of physical sciences. He insisted that this high level of civilization and slavery didn't just coexist, but were fundamentally intertwined.

In Origin of The Family, Private Property and The State, Friedrich Engels examines the development of slavery and civilization. He postulates that the advent of cattle-breeding, metalworking, weaving, and farming led to human labor producing a surplus beyond immediate necessities. This change increased the value of labor, leading to the acquisition of slaves, especially as the growth of human families couldn't keep up with the expansion of livestock. Captured enemies were employed and bred for their labor, much like cattle. Implying that, as Fitzhugh passionately argued, civilization was born out of slavery.

Fitzhugh's perspective contrasts sharply with Marx, who rejected chattel slavery and advocated for a progressive shift towards socialism through a proletarian revolution. Fitzhugh on the other hand viewed slavery as the most effective way that socialism could be implemented. He argued that wage labor inevitably falls short in meeting workers' needs due to the exploitation of their skills and the unfair distribution of their labor's results. In contrast, Fitzhugh posited that slavery could fill this gap by providing for slaves in a paternalistic manner, thereby eliminating the "greed" associated with wage labor exploitation. He maintained that the socialists' comparison of wage labor to true slavery was an insult to slavery. While wage earners and slaves had limited choice in their work, wage earners lacked the job security and adequate income that slaves were provided. He suggested that in a saturated labor market, wages were more oppressive than slavery.

“There is no rivalry, no competition to get employment among slaves, as among free laborers. Nor is there a war between master and slave… His feeling for his slave never permits him to stint him in old age. The slaves are all well fed, well clad, have plenty of fuel, and are happy. They have no dread of the future—no fear of want. A state of dependence is the only condition in which reciprocal affection can exist among human beings—the only situation in which the war of competition ceases, and peace, amity and good will arise. A state of independence always begets more or less of jealous rivalry and hostility. A man loves his children because they are weak, helpless and dependent; he loves his wife for similar reasons.”

— George Fitzhugh, Sociology For The South

Fitzhugh contended that the socialist proposal to abolish wages would result in universal slavery, with people compelled to obey those controlling essential resources. He claimed that slavery achieves the socialist goal by abolishing wages and ensuring care from masters. Fitzhugh reasoned that slaves, under their masters' care and receiving sustenance and shelter, consumed a larger share of their labor's fruits compared to Northern laborers. From this, he concluded that plantation slavery mitigates the exploitation of wage labor capitalism, returning a larger portion of the surplus value to the workers, a role similar to that played by a socialist state in a Marxist framework. His interpretation of enslavement is in perfect harmony with the principles of "From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs."

“A Southern farm is a sort of joint stock concern, or social phalanstery, in which the master furnishes the capital and skill, and the slaves the labor, and divide the profits, not according to each one’s in-put, but according to each one’s wants and necessities.“

— George Fitzhugh, Sociology For The South

Fitzhugh delves into the evolution of slavery during the fall of the Roman Empire, transitioning from personal slavery to a form where slaves were attached to land, often referring to colonial slavery and serfdom. Many historians believe this to be the birth of the feudal system. He further contrasts this system with the status of Eastern European serfs, asserting they enjoy a better quality of life and are less likely to instigate social disruption than their free laborer counterparts in Western Europe, given their modest needs and way of life. Alongside this, Fitzhugh's unique interpretation of Marxist theories inverts Marx's own suggested solutions to capital ownership issues. His defense of slavery, along with his belief in a hierarchical version of socialism, aligns Fitzhugh with the "Reactionary Socialism" of the Feudal Socialist movements, as outlined by Marx and Engels in the Communist manifesto.

“But slavery does, in practice as well as in theory, acknowledge and enforce the right of all to be comfortably supported from the soil. There was, we repeat, no pauperism in Europe till feudal slavery was abolished.”

— George Fitzhugh, Cannibals All! Or, Slaves Without Masters

A video on Feudal Socialism from the Communist manifesto

Conclusions

In the heartlands of socialism, one can discern the countenance of slavery, reflecting a profound symmetry between the two. This notion may not find favor with certain socialists of a humanitarian bent, who regard their endeavors as deeds of goodwill. Yet, those steeped in the wisdom of socialist doctrine can surely discern the truth in Fitzhugh's assertions. His intricate understanding of slavery serves to augment his contention that socialism and slavery share a common essence, apparent in their aims, rhetoric, and ultimate consequences. However charming the promises of the humanitarian socialists may be, their doctrine unavoidably paves the way to autocratic conditions reminiscent of slavery. This comparison was also echoed by other intellectuals. George Orwell, who critically analyzed German Nazism and Russian Communism as tyrannical systems, suggested that the global trend was not towards freedom but rather a resurgence of tyranny. Similarly, Ayn Rand described socialism as widespread slavery and Friedrich Hayek expressed his fears that socialism would turn free citizens into serfs.

It is with this understanding that I propose, that countries like the Soviet Union, Maoist China, North Korea, Nazi Germany, and Fascist Italy essentially functioned as vast plantations. Here, the toil of the many disproportionately benefited a small number of powerful individuals, thus engendering a dynamic reminiscent of a master and his slaves. Just as we see the purest form of socialism mirrored in slavery, so too does socialism inexorably transmogrify into a form of slavery. Slavery and generic fascism seem to represent the most candid forms of socialism, whereas Marxism and Utopian Socialism seem somewhat bewildered in this vast ideological landscape.

“Socialism, with such despotic head, approaches very near to Southern slavery, and gets along very well so long as the depot lives.”

— George Fitzhugh, Cannibals All! Or, Slaves Without Masters

For further exploration on related topics, consider the following:

Causes of The American Civil War

The American Civil War stands as a pivotal event in American history, characterized by its immense bloodshed, complexity, and far-reaching consequences. The clash between the Northern Union and the Southern Confederacy yielded a definitive outcome that would reverberate in subsequent conflicts, including the global wars of the 20th century. However, com…

I have to say that his book Sociology for the South was a massive eye opener for me. There is always something new to learn. Even being red pilled for a while that book was an extremely mind altering read. I love simple concepts that are always in front of your face that you can take for granted in these circles but when you look closer at them there is a huge pool of information there that you can miss. Great article about this concept.