Georges Valois and The Faisceau

by Zoltanous

Georges Valois and The Faisceau

Fascism, as argued by Professor Zeev Sternhell, emerged in France in the late 19th century from an alliance between the extreme right and left, where nationalism merged with socialism to form what would become the "essence of fascism." This merger was evident in movements like the "yellow movement," ( Yellow syndicalist ), neo-Boulangerist groups, and radical nationalists. French socialism struggled with its theoretical foundation, and Marxism was weakly influential. Anti-Semitism in France was more class-based, targeting financial institutions perceived as "Jewish," unlike the religious or nationalistic anti-Semitism in Germany.

The ideological roots of fascism trace back to the Belle Époque (1870-1914), with movements like syndicalism and Boulangism being "pre-fascist." Boulangism united diverse political ideologies around four key elements: transcendent leadership, a strong state, nationalism, and pro-worker social policies. These elements became central to historical fascism and were prevalent in Mussolini's regime. Syndicalism saw the emergence of "national-syndicalism," combining nationalism and socialism. Groups like Terre Libre and the Cercle Proudhon, founded by Georges Valois and Edouard Berth , exemplified this trend. Valois later established Le Faisceau, the first fascist organization outside Italy. In this organization we can note the presence of Philippe Barrès, the son of Maurice Barrès (theoretician of French nationalism).

French fascism, although less developed than in other countries, boasted a doctrinal richness. It remained untainted by power, allowing its components to be clearly discerned. This purity highlights the significance of Georges Valois’s movement, which was pioneering and dynamic, free from the compromises seen in Spain, Germany, or Italy, where fascist regimes often modified their principles to meet governmental needs. Zeev Sternhell, along with A. James Gregor and Robert Soucy, identified the Circle Proudhon as a precursor to fascism, serving as a bridge between the late 19th-century French "revolutionary right" and later fascist movements. This group brought together anarchist-influenced trade unionists, monarchist nationalists from Action Française, and socialists with pre-Marxist utopian ideals, creating a "national socialist synthesis." However, Alain de Benoist challenges this view, arguing that the Circle Proudhon's influence on broader fascist movements, including Mussolini's rise, was minimal. He contends that only revolutionary syndicalists might have been influenced, and this was more through tangible actions than intellectual theories.

Benoist questions the applicability of terms like "socialism" and "syndicalism" in Sternhell's synthesis, suggesting that figures like Berth and Sorel were more "conservative revolutionary" than proto-fascist. This debate highlights differing interpretations: Sternhell views the Proudhon Circle as proto-fascist, while Benoist sees it as part of the "conservative revolutionary" movement. This raises questions about the overlap between conservative revolutionaries and proto-fascism, with each scholar offering a partial perspective. Both terms — "proto-fascist" and "conservative revolutionary" — are ambiguous, with varying definitions and applications to figures Ernst like Jünger and Julius Evola. Sternhell's broad explanation of fascism through early French movements and Benoist's complex labeling of the Circle Proudhon reflect the complexity and nuance in understanding these historical movements.

The relationship to fascism is complex, as many movements of that time merged nationalism with progressive social policies and anti-bourgeois sentiments. These convergences often blur the lines between fascism, pre-fascism, and neo-fascism, depending on the historical context. Alain de Benoist critiques attempts to link Georges Sorel too closely with nationalism and fascism, arguing that Sorel was more aligned with patriotism and rejected Marxist internationalism, distancing him from fascism's reverence for the State.

Circle Proudhon, associated with early fascistic ideas, was diverse and not monolithic. Although Edouard Berth, one of its founders, did not share Georges Valois's views or participate in founding Le Faisceau, he recognized their attempt to challenge democracy from national and syndical perspectives as a form of pre-fascism. In Italy, Sorelian syndicalism indeed influenced the development of Fascism. Both Zeev Sternhell and Benoist mistakenly treat fascism as a singular phenomenon. In reality, fascism was multifaceted, with variations like the "fascist left," "fascist right," and "fascist center." Different groups emphasized different aspects of nationalism and socialism, leading to these distinctions. Circle Proudhon exemplified early attempts to integrate social and national ideas, contributing to the "fascist left" by embodying anti-bourgeois sentiment and exploring new ideological doctrines.

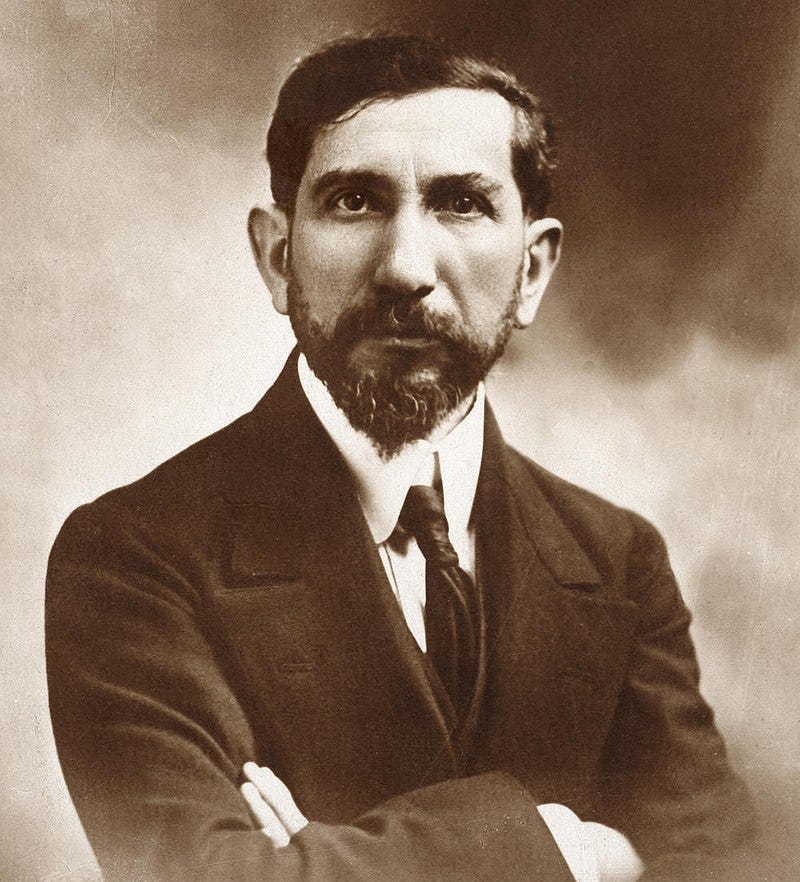

A photo of Charles Maurras

In 1913, Charles Maurras noted that the Circle Proudhon, although rooted in nationalism, welcomed diverse perspectives, including those not aligned with nationalist or royalist ideologies. The group included individuals from various backgrounds, such as federalist republicans, integral nationalists, and syndicalists, all committed to organizing French society based on Proudhon's principles and contemporary syndicalist movements.

Maurras highlighted key aspects of Circle Proudhon:

It emerged within the Action Française milieu.

Some members were not monarchists or nationalists.

Members often came from union and federalist circles.

A shared commitment to French tradition, as interpreted by Proudhon, united them.

The Circle functioned as a think tank, established in 1911 with the motto "All that is national is ours."

“The Frenchmen who have met to found the Cercle P-J Proudhon are all nationalists. The patron they chose for their assembly had them meet other Frenchmen who are not nationalists, who are not royalists, and who join them to participate in the life of the Cercle and the editing of the “Cahiers.” The initial group, of course, is made up of men of varied origins, of different conditions, who have no common political aspirations, and who will freely expose their views in the “Cahiers.” But federalist republicans, integral nationalists, and syndicalists, having resolved the political problem or cast it from their thoughts, all are equally interested in the organization of the French city in accordance with the principles taken from French tradition that they find in the Proudhonian oeuvre and in contemporary syndicalist movements, and all are in agreement on these points:

Democracy is the most serious error of the past century. If we want to live, if we want to work, if in public life we want to possess the highest human guarantees for production and culture; if we want to preserve and increase the moral, intellectual, and material capital of civilization, it is absolutely necessary to destroy democratic institutions.

Ideal democracy is the most foolish of dreams. Historic democracy, realized in the colors that the modern world knows it under, is a mortal illness for nations, for human societies, for families, for individuals. Brought among us to establish the rule of virtue, it tolerates and encourages all forms of license. Theoretically it is a regime of liberty; practically it hates concrete, real liberties and it has surrendered us to great companies of thieves and to politicians leagued with financiers or dominated by them, who live on the exploitation of the producers.

Finally, democracy has allowed, in the economy and in politics, the establishment of the capitalist regime, which destroys in the polis what democratic ideas dissolve in the spirit, that is, nations, the family, and morals, by substituting the law of gold for the laws of blood.

Democracy lives on gold and the perversion of the intelligence. It will die of the awakening of the spirit and the establishment of institutions that the French create or recreate for the defense of their freedoms and their spiritual and material interests. It is to favor this dual undertaking that we will work in the Cercle Proudhon. We will fight mercilessly against the false science that served to justify democratic ideas and against the economic systems that their inventors have destined to stupefy the working classes, and we will passionately support the movements that restore their freedoms to the French, in the forms appropriate to the modern world, and which allow them to live by working with the same satisfaction of their sense of honor as when they die in combat.

The Founders of the Cercle Proudhon and the Editors of the Cahiers:

Jean Darville, Henri Lagrange, Gilbert Maire, René de Marans, André Pascalaon, Marius Riquier, Georges Valois, Albert Vincent.”

— Declaration of Thr Cahiers du Cercle Proudhon, Cahiers du Cercle Proudhon, First Issue

The symbol of Cercle Proudhon

Maurras saw the Circle as embodying the "French tradition," akin to the historical "compagnonnage" or workers' brotherhoods, which shaped modern French syndicalism.

"The defense of French culture is today directed by Charles Maurras."

— Georges Sorel, L'Indépendance

He viewed these movements as integral to French heritage and potential allies. Unlike Jacobin nationalism, which emphasized uniformity, Maurrasian nationalism accepted regional diversity and aimed to reflect it. Therefore, building bridges between trade unionism and federalism aligned with Action Française's doctrinal goals. Maurrasianism, with its "integral nationalism," sought to broaden its appeal by engaging with sectors it considered ideologically close.

“The idea of a nation is not a 'cloud' as the anarchist cranks say, it is the representation in abstract terms of a strong reality. The nation is the largest community circle that is temporally solid and complete.”

— Charles Maurras, Mes idées politiques

The formation of Circle Proudhon was initiated by Georges Valois, who sought authorization from Charles Maurras, though Maurras initially hesitated due to his preference for René de La Tour du Pin's French corporatism over Valois's radical ideas. In the interim, Valois attempted to create a forum uniting syndicalists and nationalists outside Action Française. He even collaborated with Georges Sorel on a nationalist-syndicalist magazine, La Cité Française, which never materialized. Eventually, Valois and Henri Lagrange convinced Maurras to support the Circle Proudhon, attracting young followers of Sorel's Reflections on Violence.

The Circle, comprising republicans, federalists, national integralists, and syndicalists, rejected democracy, advocating instead for organizing French society based on Proudhon's principles and syndicalist ideas. Their declaration emphasized the need to dismantle democratic institutions to preserve cultural and moral capital. The group remained active until World War I, when many members, including Valois, were mobilized. Valois, wounded in the war, reflected on the conflict, advocating for liberation from the servitude of money and envisioning a society led by spirit and sacrifice.

“Our object is greatness. We achieve greatness through action. But thought precedes action. Before the intoxication of action, the cold calculations of intelligence, on the order of will and imagination. We seek the means to greatness.”

— George Valois, The National Revolution

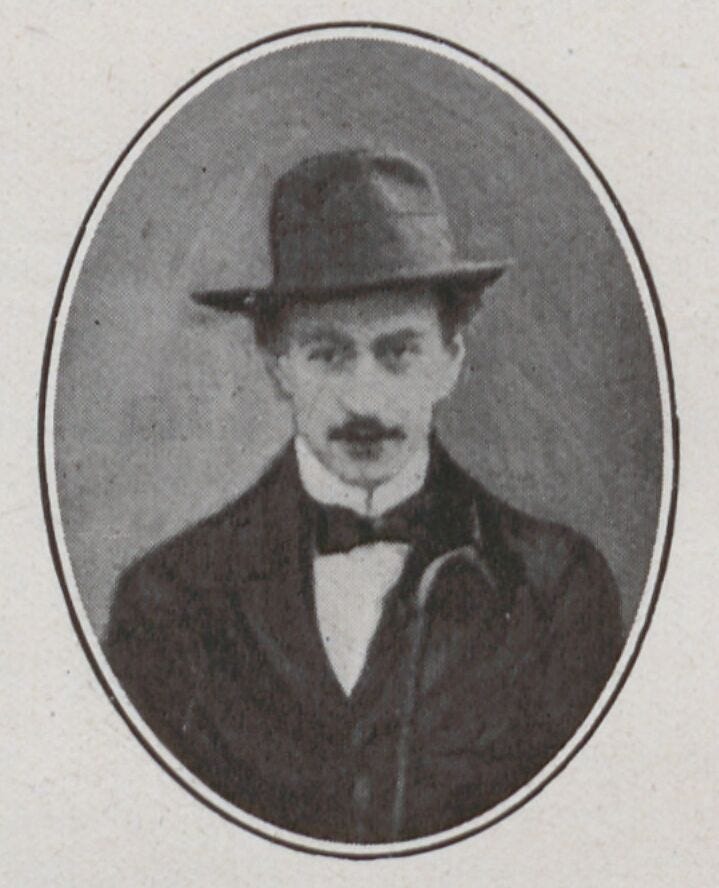

A photo of Édouard Berth

Édouard Berth, a key figure alongside Valois in forming the Cercle Proudhon, was a devoted follower of Sorel and Proudhon. A trade unionist, Berth believed the working class should be the foundation of a new society. His opposition to parliamentary democracy and admiration for classical antiquity aligned him to fascism. Berth's journey through French socialist circles eventually led him to Action Française, where he met Valois, making his role in the Proudhon Circle crucial.

“Against the rule of speculators and financiers, characterized by an essential cowardice, and which can only maintain itself through skill and cunning, there is, according to Mr. Pareto, only one recourse: that of brute force. Against gold, only iron can prevail, and that is why in this modern world, plutocratic to its core, there is such a universal prejudice against violence, and, in all classes, such a great spirit of conciliation. Transaction is, naturally, the essential law of a commercial world: in a marketplace, everything can and must be negotiated. Finance, as Nietzsche said in the passage I cited earlier, promotes the power of the average, that is to say, of mediocrity, which, in the absence of any strong conviction, is always in favor of 'tolerance,' 'freedom,' and 'negotiation.' It will attack, it will silently undermine all movements of ideas that could make a value superior to market value prevail. It will corrode Catholicism through modernism, which is essentially a transaction between Christian Faith and the modern world; Philosophy through pragmatism, which is philosophical modernism; Socialism and Nationalism through parliamentarianism: everywhere, in short, where it senses a spirit of warlike intransigence likely to establish and maintain against it some Absolute and some Supernatural within this universal naturalistic relativism of the modern world, so favorable to its reign, it will immediately try to undermine, envelop, and 'pacify' it [...].”

— Édouard Berth, Satellites of Plutocracy

After World War I, Édouard Berth briefly flirted with Bolshevism but quickly rejected it due to the USSR's bureaucratization, despotism, and what he termed "termitism" — the depersonalization of masses for state interests. By 1935, he returned to revolutionary syndicalism, a path he had left in 1909, and he passed away in 1939. Berth believed that Sorel's and Maurras ideas complemented each other, likening them to Nietzsche's concepts of the Apollonian and Dionysian spirits, suggesting a fusion could herald a new era.

A photo of Georges Valois

Georges Valois found that organizing structures outside Action Française was premature without resources or a unifying cause. At that time, Action Française was seen as a workerist opposition movement, allowing potential outreach to leftist unionism. Henri Lagrange, another key figure, had been arrested multiple times and became a student idol after a controversial imprisonment. His radical activism led to his expulsion from Action Française in 1913, and he died in 1915. Whether Valois or Lagrange initiated the Proudhon Circle remains debated, but Lagrange had long sought to establish an economic study group within Action Française.

A photo of Henri Lagrange

The Proudhon Circle's journal, Cahiers du Cercle Proudhon? was intended to be quarterly starting in 1912, but only four issues were published, two as double issues. The journal featured contributions from Berth, Lagrange, Valois, and others. Most readers were Action Française members, and the content focused heavily on Proudhon and Sorel. Despite plans for a new format, the journal was discontinued after 1913, with Berth often writing under a pseudonym.

The Circle Proudhon’s initial activities included an internal meeting at the Action Française headquarters on October 3, 1911, and a public conference in Paris on December 16, attended by Charles Maurras to show his support. Despite this promising start, the Circle struggled to maintain momentum, and its publications failed to gain interest beyond Action Française. Only a few left-wing figures collaborated, alongside Édouard Berth.

Georges Valois, in the first issue of the Circle's journal, claimed the right to present both "revolutionary" and "counter-revolutionary" ideas, anticipating contradictions. Though Georges Sorel subscribed to the journal, he remained skeptical and advised Berth to be cautious with his new allies. Sorel doubted the Circle's success, believing it wouldn't help young people truly understand Proudhon due to its ties to Action Française. As a result, Berth used a pseudonym for his writings.

The Circle's efforts to win over Sorel failed, and despite a commemorative dinner in May 1912 praising Sorel's influence, he remained disengaged. The broader French anti-Marxist left also reacted coolly, with figures like Hubert Lagardelle criticizing the journal as a reactionary attempt to co-opt the workers' movement. The onset of World War I effectively ended the Circle's activities, but it likely would have dissolved on its own due to its lack of success and support. The Proudhon Circle was an attempt to synthesize nationalist and social ideas, a concept that later found expression in fascism and Mussolini's policies. The Circle's failure highlights that while some early 20th-century thinkers sought this synthesis, they didn't achieve it themselves.

The Circle was named after Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, a figure who opposed Marxist ideas, advocating for federalism over internationalism and promoting workers' rights through cooperatives and trade unions. Proudhon believed workers had a homeland, unlike uprooted capitalists, an idea echoed by Édouard Berth. While Marx criticized Proudhon as vain and superficial, Action Française and its affiliates viewed him as a conservative and counter-revolutionary thinker, aligning with their anti-Jacobin and anti-democratic sentiments. They honored Proudhon, associating him with French patriotism and criticism of revolutionary and collectivism.

A photo of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon

The Circle aimed to attract Georges Sorel, who had written about Proudhon, by adopting his name. However, their efforts to incorporate his ideas and appeal to Sorel did not succeed, as Sorel remained detached from the initiative. Circle Proudhon had numerous challenges in adapting Proudhon's ideas, primarily due to internal disagreements within Action Française and among its members. While Action Française drew inspiration from René de La Tour du Pin and Christian corporatism, Proudhon was viewed as an adversary by some members. Charles Maurras, although supportive of the Circle on an experimental basis, had mixed feelings about it.

Within the Circle, discord was evident between Édouard Berth and Georges Valois. Berth criticized Valois for attempting to revive outdated corporatism, while Valois dismissed Berth's socialism as antiquated. Their ideological differences persisted after the Circle dissolved, with Berth continuing to believe in class struggle and Valois advocating for class unity. Post-war, their paths diverged further, with Valois briefly tempted by fascism and Berth by Bolshevism.

The Life of Georges Valois

Georges Valois, born Alfred-Georges Gressent, had a complex political journey. Initially involved in left-wing anti-parliamentary monarchism, he later founded the Circle Proudhon within Action Française. Valois's life was marked by ideological shifts, from early anarchism to national syndicalism and ultimately to participating in the French Resistance during World War II. His multifaceted political identity has made him a controversial figure, often described as oscillating between the left-wing and right-wing. Valois's life highlights the instability of left-wing fascism and pre-fascism, with his political journey reflecting the broader tensions and contradictions within these movements. Despite his varied ideological affiliations, Valois's influence remains significant in the context of early 20th-century political thought.

In 1912, Georges Valois transitioned from working at a bookshop to managing the Nouvelle Librairie Nationale, becoming a prominent figure in Action Française, known for his economic views on the extreme right. He focused on "social economy," advocating for trade unionism and guilds as counterforces to the financial sector, which he criticized for its parasitic nature. During World War I, Valois served at Verdun until 1916, gaining attention for his innovative ideas on armored warfare, particularly the concept of assault tanks. Post-war, he began distancing himself from Action Française, a break delayed by his respect for Léon Daudet, whom he credited with saving his life. Ultimately, Valois founded Le Faisceau des Combattants et des Producteurs, marking another significant shift in his political journey.

Valois's early political evolution was influenced by Georges Sorel, whom he met at various liberal groups. Sorel's ideas on trade unionism, class struggle, and the failings of capitalism deeply impacted Valois. Sorel criticized social democracy and Marxism for neglecting the middle classes and emphasized the need for a revolutionary aristocracy rooted in union struggles. He rejected parliamentarism, viewing it as an expression of bourgeois mediocrity, and was critical of the bourgeoisie's "myth of progress." Sorel's influence moved Valois toward the radical left, highlighting his ideological journey from right-wing economic thought to embracing revolutionary syndicalism and radical leftist ideas. This shift underscores the complexity and fluidity of Valois's political beliefs throughout his life.

Georges Valois's early work, influenced by Sorel, reflected ideas similar to those of Mussolini's early left-wing fascism, emphasizing revolutionary syndicalism, strong governance against liberalism, and opposition to plutocracy. His manuscript L'Homme qui vient was shared with Paul Bourget and Charles Maurras, leading to Valois's involvement with Action Française. Despite initial alignment on anti-capitalist views, tensions between Valois and Maurras arose over economic and social issues, culminating in a significant ideological split by 1926.

“To the financier, the oilman, the pig breeder who believes himself to be the masters of the world and wants to organize it according to the law of money, according to the needs of the automobile, according to the philosophy of pigs, and bend the peoples to the dividend policy, the Bolshevist and the fascist respond by raising the sword. Both proclaim the law of the combatant. But the Slavic Bolshevist arms his arm to set out to conquer the wealth accumulated in the Roman world. The Latin fascist raises the ax to establish peace and protect the plowman against the usurer. It is not by chance that the reaction against the bourgeois regime produced Bolshevism in Russia and fascism in Italy. The Slavic Bolshevist is the warrior of the North, who places himself at the head of the Asian and Scythian hordes and to whom his doctrine provides justification for setting out to plunder the Roman world, which he calls the capitalist world. The Latin fascist is the fighter from the South, who wants to wrest the State from the feeble hands of the bourgeois administrator, protect work against the money-grubber, and straighten out the defenses of civilization abandoned by the mercantis and incapable jurists. to bear arms.”

— Georges Valois, The National Revolution

Sorel and Maurras shared a disdain for republican institutions and bourgeois mediocrity, though they diverged on issues like Maurras's views on Jews, foreigners, Protestants, and Freemasons, which did not interest Sorel. Valois's break with Maurras was influenced by these ideological differences and was exacerbated by Valois's launch of the Cahiers des États Géneraux, which adopted Mussolini's theses and signaled a shift towards fascism.

Valois led the Nouvelle Librairie Nationale from 1912, publishing works with a nationalist and revolutionary syndicalist perspective. After his split from Maurras in 1925, the bookstore aligned with Valois's new movement, Le Faisceau, focusing on corporatism and fascism. Throughout its existence, the bookstore published around 300 political works categorized into various collections, including the Proudhon Circle Collection and the Nouveau Siècle Collection.

The conflict between Maurras and Valois intensified with the transformation of Valois's journal into Le Nouveau Siècle, which promoted national unity and further distanced him from Maurras. This period marked Valois's shift towards fascism and the final rupture in his relationship with Maurras and Action Française. Le Nouveau Siècle, launched on February 26, 1925, under Georges Valois and Jacques Arthuys, quickly became the voice for the emerging fascist movement Le Faisceau. The journal, originally supported by a committee of businessmen with ties to Action Française, aimed to promote national unity and was initially conceived as a weekly, later becoming a daily publication. Contributors included prominent right-wing journalists, many of whom were also involved with Action Française. However, the publication faced immediate challenges. Charles Maurras, leader of Action Française, saw it as a threat to his own weekly and pressured contributors to choose sides. Most, except Philippe Barrès, returned to Maurras, significantly weakening Le Nouveau Siècle's editorial board and financial backing. Financial support from François Coty was also withdrawn to avoid conflict with Maurras. Additionally, the journal's attempt to appeal to a more moderate audience alienated its activist base, composed mainly of former combatants and early admirers of Mussolini in France.

The journal's failure was evident just ten days after its launch, leading to an increasingly bitter relationship with Maurras, which limited Valois's political influence. Despite these setbacks, Valois continued to advocate for a new national movement, culminating in the founding of Le Faisceau on November 11, 1925. This movement, inspired by Italian fascism, aimed to organize society into Faisceaux of combatants, producers, citizens, and youth, reflecting Valois's vision of a modern, nationalistic state. Throughout this period, Valois praised Mussolini, viewing Italian Fascism as a model for France to develop its own nationalistic methods.

Relations between Georges Valois and Charles Maurras of Action Française soured due to both ideological and financial conflicts. Valois criticized the bourgeoisie for France's decline, while Maurras blamed external groups, leading to a rift. Financial struggles ensued for Valois's movement, Le Faisceau, as Maurras feared losing resources. However, Valois attracted some left-wing support, distinguishing himself as a more radical alternative to Maurras, adopting Italian fascist methods like paramilitary formations.

Tensions escalated in December 1925 when Maurras's followers attacked Le Faisceau and slandered Valois, accusing him of theft and espionage. Valois eventually sued, and the courts ruled in his favor, though the damage was done. By the time the verdict was reached, Le Faisceau was declining, reverting from a daily to a weekly before disappearing in 1928. Despite a judicial win, Valois failed politically; militarism didn't appeal to the French, and the movement was seen as an imitation of Italian fascism. Valois's renouncement of anti-Semitism also alienated some supporters. Le Faisceau's membership figures remain uncertain, with Valois claiming 25,000 members, a number historians find plausible. However, the claimed circulation of Le Nouveau Siècle at 300,000 was likely exaggerated, with one-third being more realistic.

Zeev Sternhell identified Le Faisceau as a true prototype of fascism ideologically and in political action, though unlike typical fascist movements, it did not initially seek violence. Its security service was only formed in response to ongoing attacks from Action Française, its main adversary. Le Faisceau's major confrontation with the far left occurred during a June 1927 meeting in Reims, where 4,000 communists protested. The clash was violent, necessitating police intervention and causing citywide riots. Previously, in February 1926, Le Faisceau held its first mass demonstration in Verdun, showcasing a new political style in France with military parades and uniformity, reminiscent of Mussolini's fascism. Despite similarities, direct connections between Mussolini and Valois remain debated, and by January 1928, Valois criticized Italian fascism for abandoning its revolutionary roots.

Efforts to prove collusion between Italian and French fascists were inconclusive. A 1925 police note mentioned the Duke of Camastra as a possible funder, but this wasn't verified. French police heavily monitored Le Faisceau from its inception, documenting every event and action. The precautions taken, including increased phone tapping, suggest the movement was perceived as more significant than it may have been. In early 1926, Georges Valois sought to strengthen his movement, Le Faisceau, with new initiatives like a doctrinal magazine, but was hindered by limited resources. The return of Raymond Poincaré to power later that year with financial austerity measures reduced the need for Le Faisceau, which had initially thrived under a left-wing government by promising to mobilize against the left. With Poincaré stabilizing the financial crisis, support for Le Faisceau dwindled.

As the financial situation in France improved, Le Faisceau struggled, facing internal splits and loss of financial backing. Dissidents from both the right and left criticized Valois, leading to a decline in membership and influence. By early 1927, key figures left the movement, marking its downfall. Realizing the end was near, Valois shifted back to the conventional left and founded the Republican Syndicalist Party in mid-1928, drawing some former members of Le Faisceau and new recruits. This new party, left-wing and anti-fascist in orientation, aimed to explore a corporatist economic model through its publication, Cahiers Bleus. Contributors included diverse figures from various political backgrounds. Meanwhile, the remaining fascist elements formed the Revolutionary Fascist Party, which failed to gain traction in French society.

Valois, whom was initially affiliated with Action Française and Le Faisceau, shifted significantly to the Marxist left by the 1930s. After contributing to an encyclopedia on labor, Valois became involved with the journal Nouvel Âge, promoting a distributive economy and a classless society. His political transformation led him to attempt joining the SFIO in 1935, though he was rejected. During the Spanish Civil War, Valois criticized the French left's stance and advocated for pacifism and anti-fascism, opposing the Munich Agreement and suggesting economic sanctions against Germany and Italy. Notably, Action Française also viewed fascism as anti-French by this time.

"There are certain conservatives in France who fill us with disgust. Why? Because of their stupidity. What kind of stupidity? Hitlerism. These French 'conservatives' crawl on their bellies before Hitler. These former nationalists cringe before him. A few zealots wallow in dirt, in their own dirt, with endless Heils. The wealthier they are, the more they own, the more important it is to make them understand that if Hitler invaded us he would skin them much more thoroughly than Blum, Thorez and Stalin combined. This 'conservative' error is suicidal. We must appeal to our friends not to let themselves be befogged. We must tell them: Be on your guard! What is now at stake is not anti-democracy or anti-Semitism. France above all!"

— Action Française quoted in World in Trance by Leopold Schwarzschild

When World War II began, Valois was in Bayonne but fled to Morocco after the German invasion. He was arrested in late 1940 but released in 1941 due to lack of evidence against him. Valois then moved to Vichy, initially planning to join the resistance but ultimately deciding he was too recognizable for clandestine work. He settled in Val d'Ardières, where he attempted to live a visible life to avoid suspicion, opening a small hotel and receiving friends.

Valois, in an effort to maintain a low profile during the German occupation of France, produced pamphlets on the history of cooperatives and gardening, which appeared harmless to the occupiers and Vichy government. He had about 200 subscribers, with a select few receiving political content. In 1943, he launched a clandestine magazine called Après, under the pseudonym Adam, publishing significant works like France Betrayed By The Trusts. Despite his caution, Valois's activities attracted the attention of the Gestapo in Lyon, led by Klaus Barbie. Although initially dismissed as a naive idealist, Valois and his secretary were sentenced to death, later commuted to imprisonment in concentration camps. While his secretary survived the ordeal, Valois was deported to Neuengamme. There, he envisioned ambitious plans for reconstructing the left and reforming the global economy, but he succumbed to typhus on February 18, 1945, shortly before the end of World War II.

An aged Valois