Inejiro Asanuma: Japan's Nationalist Martyr

by Zoltanous and Zero Schizo

Introduction

Picture a nation rising from the ashes of a catastrophic global conflict, unjustly held responsible and laden with crippling debts. This period sees the nation spiralling into economic hardship, societal impoverishment, and cultural decline. Amidst these dire circumstances emerges a leader who empathizes with the populace's plight, rallying them towards a resurgence of national pride and collective ambition. This leader, distinguished by extraordinary virtues and leadership skills, resonates deeply across a broad spectrum of society, notably marked by his affection for dogs and even garnering respect among political rivals. He is often linked with the term "National Socialist." Yet, it's crucial to note that this narrative does not revolve around Germany or Adolf Hitler. Our focus is on Inejiro Asanuma, a figure celebrated in Japan and other Asian regions but relatively unknown in the West. Western narratives frequently misrepresent Asanuma as a communist, obscuring his actual contributions. His legacy is predominantly associated with his public assassination by 17-year-old Otoya Yamaguchi, an act that has, regrettably, been trivialized into meme content by certain right-wing factions.

Right wing western art depicting the assassination

The belief that Otoya Yamaguchi's assassination of Asanuma saved Japan from communism is a baseless myth that lacks factual evidence. This narrative, largely originating from English sources, does not align with the historical reality of that period in Japan. It is crucial to recognize a flaw in the analysis of post-1945 geopolitics, which mistakenly equates socialism and socialist ideas with communism within the framework of Marxist-Leninist ideology. It is important to note that after World War II in 1945, Third Positionist ideas and movements could no longer openly identify themselves as Fascist or Nazi due to the negative connotations associated with these labels. An example of this can be seen in the leadership of Juan Perón in Argentina.

As a result, many adherents of Third Positionist ideologies sought associations and common ground with those in the Second Position (Marxists and Communists) to effectively combat international finance and world capitalism. Therefore, it becomes clear that the collaboration between these ideological factions was driven by a shared objective rather than a preservation of Japanese society from communism. This understanding challenges the notion that Yamaguchi's actions were motivated by a desire to protect Japan from the perceived threat of communism. Inejiro Asanuma truly exemplified the post-war trend previously discussed. Though sometimes inaccurately described as a "National Socialist," Asanuma was a key member of the Nationalist wing of the Japan Socialist party, with his ideology and actions significantly shaped by the legacy of Japan's Imperial era.

The Legacy of Inejiro Asanuma

Inejiro Asanuma was born on December 27, 1898, in Miyake, Tokyo, and began his political career by joining ultra-nationalist youth groups that formed in Japan following World War I. He gained prominence through his involvement with the Builder's Alliance, a student movement established in 1919 amidst the Taisho democracy period. Asanuma's political alignment shifted towards socialism, where he became an active supporter of labor and peasant rights throughout Japan. At a student-led protest at Waseda University's Military Research Department, he advocated for collaboration with the military, a stance that resulted in a physical assault by those with opposing views on that very day. Asanuma's ideology, similar to Adolf Hitler's blend of socialism and nationalism in Germany, championed the integration of these two philosophies. He argued that true socialism in Japan could only flourish under the banner of Japanese nationalism, a belief shaped by his deep engagement with the writings of Ikki Kita, a proponent of Japanese National Socialism.

After graduating from Waseda University's School of Political Science and Economics in 1923, Asanuma devoted his life to the political scene in Japan. By 1925, at the age of 26, he helped establish the Farmer-Laborist party, a nationalist syndicalist group that embraced the notion of class struggle. Despite being named by the Farmer-Labor party's general secretary as a promising leader for Japan's first proletarian party, the government quickly declared the party a threat to the imperial order and disbanded it within an hour of its creation. Nonetheless, Asanuma's resolve to influence Japanese politics remained strong, undeterred by governmental suppression.

“After this event, he began veering towards a “national socialism”. To be clear, it is more “National Bolshevik” than it is a Hitler-esque movement.”

— Alimentary Machinations, Remembering Asanuma Inejirō, Yamaguchi Otoya and The Turbulent Postwar Period

In 1926, the Laborist-Farmer party was established by Asanuma, blending nationalist sentiments with a socialist ideology firmly opposed to Marxism. The party found a base of support among Japanese trade unions, notably the Nihon Rōdō Kumiai Hyōgikai, adopting a national syndicalist (proto-fascist) stance. This approach quickly gained traction among the agricultural sector, resulting in swift growth in membership. By 1928, membership had soared to over 90,000. However, the government banned the party that same year due to its increasing influence.

Following this, the party splintered into three separate factions:

The Social Democratic party (Social Democracy)

The Japan Labour-Farmer party (the National Socialists)

The Labor-Farmer party (the Communists)

Beginning in 1932, Asanuma came under surveillance by authorities worried about possible seditious actions against the Imperial state, even though there was no concrete proof of these allegations. It's important to highlight that Asanuma was in fact in favor of the state's policies in Manchuria, responding to China's aggressive behavior. That year, he also established the Social party of The Masses, promoting a totalitarian governance model that emphasized corporatism, nationalism, and the military's role.

“Among the Party leaders were those who had great expectations of the young officers to topple capitalism and resolutely carry out domestic reform. Consequently, the power within the party gradually tilted toward National Socialism.”

— Transformation of The Proletarian Political Parties by Modern Japan Archives

In October 1934, Asanuma endorsed a pamphlet titled Kokubo no Hongi, Kyoka no Tesho, published by the Army Ministry's newspaper group. The original drafts of the pamphlet were prepared by Sumihisa Ikeda, Ryoji Shikata, and Teiichi Suzuki, who were students dispatched to the University of Tokyo from August 1933 to March 1934. After undergoing examination by the newspaper group led by Hiroshi Nemoto from March 1934 to February 1936, the pamphlet received approval from Tetsuzan Nagata, Director of the Military Affairs Bureau, and ultimately from Senjuro Hayashi, Minister of the Army. Notably, the content of the pamphlet was more detailed and concrete compared to Ikki Kita's Japan Remodeling Bill Outline. Its advocacy for the establishment of a corporatist state and the adoption of a planned economy led by the military sparked controversy at the time.

Asanuma found himself in disagreement with Aso Hisashi, who advocated for maintaining the monarchist system with the military as an auxiliary through an alliance. Conversely, Asanuma disagreed with this approach, considering Hisashi to be a conservative lacking revolutionary spirit due to his unwillingness to fully support military control. In 1933, Asanuma strongly supported military intervention in China and the necessary expansion of Japan, driven by the challenging geopolitical circumstances of the time. It became increasingly apparent that Japan needed to expand its influence to protect both the nation and Asia from the exploitation and perils posed by the expanding capitalist imperialism of America and Britain. In 1933, Asanuma achieved a significant milestone in his political career by becoming a member of the Tokyo City Hall, which greatly enhanced his popularity in Japanese politics. By 1936, he secured a seat in the House of Representatives. In 1940, Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe established the Taisei Yokusankai, and Asanuma was appointed as the Deputy Director of the Department of Investigations for Temporal Elections. During this time, Asanuma, along with Takao Saito, criticized the government and military's approach to continuing the war effort, perceiving it as an ongoing quagmire.

In 1940, when the Imperial Rule Assistance Association was formed, Asanuma assumed the position of Deputy Director of the Extraordinary Electoral System Research Department. In the same year, his rival, Aso Hisashi, passed away from a heart attack, making Asanuma the uncontested leader of his party. Asanuma then threw his support behind Hideki Tojo over Konoe. Notably, due to the emotional distress caused by his rival's death, Asanuma did not participate in the 1942 elections. This period of political inactivity led to General Tojo becoming the sole viable candidate, reinforcing the perception that he was the only capable leader for Japan during the war. However, Asanuma did participate in the Metropolitan Conference of Tokyo as a candidate and was elected Vice President of Tokyo. Despite this success, Asanuma ultimately failed in his attempt to modify the national constitution according to his vision.

Following Japan's surrender to America, Asanuma shared a poignant account of being in his Shenzhen apartment when news of Japan's surrender reached him. He described listening to the Emperor's speech as the most painful experience of his life, a moment that brought him to tears on one of the few occasions. On September 2, 1945, Japan and the United States signed a peace treaty, officially ending the war between the two nations. This event brought a sense of humiliation to the Japanese people, including Asanuma. The Allies proceeded to occupy Japan until 1952, exerting complete control over the country. General Douglas MacArthur, appointed by President Harry S. Truman, became the supreme commander of the Allied Forces and oversaw the occupation of Japan. Upon his arrival in Tokyo on August 30, 1945, MacArthur effectively assumed dictatorial powers in Japan and implemented new laws under a revised constitution. From 1945 to 1952, Japan underwent a significant demilitarization process, while the United States established various military bases throughout the country. Japan became a strategic point in the fight against communism in China, Vietnam, and Korea. The country also experienced economic and social liberalization. Asanuma recognized that Japan would inevitably undergo "Americanization," with its economy and society being influenced by American ideals, as promoted in the new constitution's "civil liberties."

The imposed constitution granted women the right to vote, abolished nobility, and reduced the Emperor to a purely symbolic figure with no political power. The Imperial House could no longer modify its own rules for succession without passing legislation through a body governed by a social contract. The American-written "new constitution of Japan" undermined imperial autonomy and disregarded long-standing Japanese traditions. Additionally, Japan lost its sovereign right to declare war. These changes were imposed against the will of the Japanese people, who held deep dissatisfaction but were unable to freely express their discontent. In many ways, this marked the decline of Japanese civilization. Japan was subjugated, humiliated, and its spiritual essence insulted, while its sacred institutions were disrespected. It seemed as if Japan was stuck in a perpetual state of 1945.

For the first time, Freemasonry was allowed to exert its full influence in Japan, as it had previously been outlawed as subversive and dangerous. Moreover, Japanese individuals residing in countries where Freemasonry was prevalent were prohibited from joining. Starting in the 1950s, American Freemasonry began to spread throughout Japan. Masonic Lodges emerged across the country, initiating the first generation of Japanese Freemasons. The standard vetting process for becoming a Freemason, typical in American Freemasonry, was conducted by the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI). To this day, the majority of the Japanese population remains unaware of how the propagation of American Freemasonry in Japan has influenced their current status as a vassal state of the United States. During the early years of this extensive American subversion operation, Inejiro Asanuma emerged as a prominent leader against the Americanization of Japan. On November 2, 1945, exactly two months before Japan's surrender, the Socialist party of Japan was founded, with Asanuma assuming the position of third in line for party leadership, behind Kawakami Kutaro and Miwa Masanori, both of whom were familiar faces from Asanuma's days as a nationalist activist.

The flag of the Japan Socialist party

In 1947, the Socialist party of Japan saw a change in leadership as Tetsu Katayama, a reformist, replaced Suehiro Nishio as the General Secretary. Katayama advocated for cooperation with the Americans and a departure from the party's previous stance of resisting the occupation and fighting for Japan's national independence. He was re-elected as Prime Minister later that year and held office until March 1948. During this time, Katayama's government became subservient to the occupiers' interests, particularly General MacArthur, who was often referred to as the "American Caesar." This decision sparked anger among various factions within the party, including Asanuma. He strongly criticized Katayama, accusing him of betraying Japan and being a sell-out. Asanuma quickly emerged as the leading voice of the Nationalists within the party, sharing the view that the occupation was humiliating and that Americanization posed the greatest danger to Japan. Consequently, he advocated for the restoration of sovereignty by completely expelling American influence from Asia.

When Tetsu Katayama, the chairman of the House of Representatives, was defeated in the 24th general election in 1949, the Socialist party nominated Asanuma as his replacement. Asanuma became the General Secretary of the Japanese Socialist party, which marked him as a major adversary of the United States and led to his inclusion on their blacklist. In 1951, the formalization of the San Francisco Peace Treaty and the Japan-US Security Treaty further fueled Asanuma's outrage. He believed that these agreements granted America indefinite cultural, economic, and political control over Japanese society. In response, Asanuma held a meeting where far-left and radical nationalist groups united against American occupation, also denouncing the Liberal Democrat party as anti-patriotic and a tool of international capitalism, aiming to subjugate the Japanese people to the influence of Washington and Wall Street.

“In 1951 (Showa 26), the Japan Socialist Party was divided into two factions -- the Right faction and the Left faction -- due to differences over the San Francisco Peace Treaty and the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty. In April 1954 (Showa 29), the two factions announced a joint statement on linking up with each other. In January 1955 (Showa 30), the two factions began negotiations for unification. On 13 October, the two factions held the 12th meeting of the Japan Socialist Party and decided to join hands again, leading to their integration. This declaration paper was read out at the 12th meeting of the Japan Socialist Party.“

— Unification of Japan Socialist Party by Modern Japan Archives

The post-WWII constitution of Japan, written by Americans rather than the Japanese people, caused widespread discontent. The Japanese Socialist party opposed it, while factions within the so-called "Nationalist" and "Right Wing" groups supported it. As the General Secretary of the party, Asanuma worked tirelessly to garner support for his comrades across the country, earning him the nickname "the human locomotive" due to his immense vitality and drive. The growing division between the right-wing radicals and the leftist factions within the party eventually led to its gradual disintegration. Unable to halt the division, Asanuma began to combat the leftist line of the party and diminish its influence, becoming frustrated with his comrades and accusing them of being sell-outs and capitalists.

“There were many divisions within the party, the most prominent of all between the radical Marxist-Leninists and the national socialists with more centrist social democrats. This division was finally made concrete in 1951, when the Treaty of San Francisco was signed. The Japanese right-wing did not protest and agreed with the signing of the treaty, while the Japanese left-wing was outraged and opposed it vigorously. Asanuma ultimately opposed the treaty, and the Japanese Socialist Party was split into the Rightist Socialist Party and the Leftist Socialist Party, and Asanuma was made the secretary-general of the Rightist Socialist Party. However, the party reunified in 1955 and Asanuma was once again made the secretary-general of the unified Japanese Socialist Party.”

— Alimentary Machinations, Remembering Asanuma Inejirō, Yamaguchi Otoya and The Turbulent Postwar Period

Asanuma was known for his staunch anti-communist stance, openly criticizing the Soviet Union and drawing parallels between its imperialistic ambitions and those of the United States, particularly in their efforts to exert dominance over nations within their respective spheres of influence. He went so far as to accuse communists of lacking patriotism, equating them to capitalists in this regard. This provocative rhetoric led some communists to brand him as a "Fascist." Additionally, it was widely recognized that within his own party, Asanuma was associated with the Right Wing faction, further highlighting his ideological alignment.

“The secretary-general of the recombined party is Inejiro Asanuma, a Right Winger.”

— Cecil H. Uyehara, The Social Democratic Movement

Asanuma enthusiastically supported the "Non-Aligned Movement" and praised leaders like Nasser and Sukarno. He believed that Japan's destiny lay in non-alignment with any superpower, as this would be the only way for Japan to establish its own sovereignty. Asanuma held up Sukarno as a model to emulate for the new Japanese nation. In 1955, when the Japanese Socialist party reunited, Asanuma became the General Secretary. During this time, he aimed to foster greater internal unity within the party and revived the past project of Ikki Kita’s National Socialism. Asanuma embraced Pan-Asianism as a realistic path to free Asia from the dominance of American-led international capitalism. He reaffirmed Japan's destiny to lead the charge for a Great Asian Union.

His latest program included the following tenets:

The expulsion of all American and Western influence

The reclamation of national sovereignty

A modified version of the post-1945 constitution

A newly created modern military

The establishment of a Great Pan-Asian Union

Corporatist economic reforms within a democratic framework

Anti-imperialism

Anti-freemasonry

Anti-communism

Anti-capitalism

During this period, Asanuma actively participated in meetings and made numerous appearances on television programs, where he voiced his concerns about what he perceived as the United States' efforts to undermine Japanese identity. He emphasized the importance of countering imperialism in Asia by defeating international capitalism. However, his media presence often drew antagonism, with some outlets ridiculing him and falsely accusing him of being a communist. Notably, Takeo Fukuda, a prominent figure in the Liberal Democrat party, engaged in a direct confrontation with Asanuma, with each accusing the other of unfavorable affiliations. Asanuma claimed that Fukuda was connected to the CIA, while Fukuda labeled Asanuma as insane.

Asanuma firmly believed that since the outbreak of the war in China in the 1930s, Japan had fallen under the control of a vast international conspiracy, similar to the forces of international capitalism and liberalism that had caused the downfall of Hitler's Germany and Mussolini's Italy. In 1959, the Sino-Soviet split occurred, and Asanuma expressed satisfaction with this development. Despite his ideological differences with Marxism, Asanuma admired Mao and considered him a remarkable Asian patriot who fiercely defended his homeland from imperialism, regardless of whether it came from the United States or the Soviet Union. Asanuma's praise for Mao's efforts to break free from the Soviet sphere of influence and restore China's sovereignty as an independent nation highlighted his recognition of Mao's commitment to safeguarding China's interests.

In 1959, Asanuma embarked on a visit to China, during which he had the opportunity to meet with Mao Zedong and other prominent leaders. It was during this visit that Asanuma developed a strong enthusiasm for the idea of a Sino-Japanese alliance aimed at countering Soviet and American influence. This newfound enthusiasm reflected his belief in the potential benefits of collaboration between China and Japan as a means to confront shared challenges and assert their respective sovereignties.

Asanuma with Mao

On March 12, 1959, Asanuma delivered a speech in China:

“I think that human beings are the ones who solve these problems as soon as possible and mobilize all their strengths to struggle with nature. This struggle cannot be done without the practice of socialism. China has now settled all contradictions and is concentrating on nature. Here you can think of the progress of the socialist state. I pray for victory in this struggle. We, the Japanese Socialist Party, also struggled with capitalism and struggle with imperialism in Japan to overcome the contradictions of capitalism and imperialism, resolve domestic contradictions, and then resolve all contradictions.”

— Inejiro Asanuma, United States Imperialism Is a Mutual Enemy Between Japan and China

Asanuma advocated for fostering relations with China as a strategy to bolster resistance against the United States, viewing American Imperialism as a common adversary for both China and Japan, and indeed, the wider Asian continent. He believed that an alliance with Maoist China could play a pivotal role in overcoming American Imperialist influence. His actions, including visits to China, public speeches, and declarations, stirred considerable debate across various segments of Japanese society. Strategically, aligning with Maoist China, a dominant anti-American and anti-Soviet force in the region, seemed logical to Asanuma. Furthermore, Asanuma held Kim Il-Sung in high regard, perceiving him as a leader who had deviated from orthodox Marxism. This respect contributed to his vision of a socialist-nationalist coalition in the Far East, led by prominent figures including himself, Mao, Kim, and Sukarno. However, his return to Japan marked by his choice to wear a Mao suit, sparked criticism, including from his socialist peers, leading to intensified internal opposition. His behavior and ideological stance led some within his party to question his judgment and dismiss him as a "charlatan."

In a move to dissociate from Asanuma's controversial positions, Suehiro Nishio and others exited the Japanese Socialist party to establish the Socialist Democrat party. The resignation of Chairman Suzuki subsequently allowed Asanuma to ascend to party leadership. He played a crucial role in security policy debates and was instrumental in prompting the resignation of Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi's cabinet, although he fell short of achieving the security treaty's abolition. Between 1959 and 1960, Japan witnessed a surge in anti-American sentiment, particularly in the lead-up to the 1960 elections, with students and workers protesting in the streets. Asanuma stood out as a key figure in these demonstrations, marking his significant influence on the political landscape during this tumultuous period.

A picture of the 1960 protests

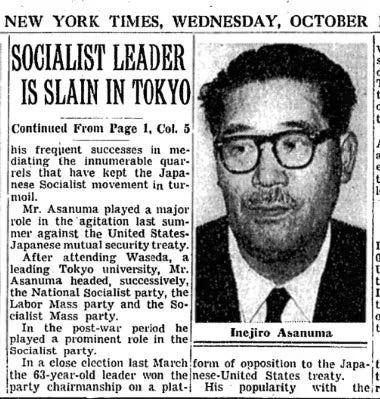

During this period, Asanuma gained widespread popularity in downtown Tokyo, to the extent that a newspaper reporter who spoke negatively of him was physically confronted by local workers in a cafeteria. His powerful public speaking skills resonated with workers and students who were actively protesting in the streets. Despite facing internal opposition, Asanuma announced his candidacy for the upcoming November elections. Interestingly, later documents would reveal that authorities closely monitored Asanuma, similar to how dissidents are monitored by the FBI in the United States today. On October 12, just a month before the elections, Asanuma engaged in a parliamentary debate against Hayato Ikeda, the leader of the Democratic Liberal party. The debate, attended by approximately 2,500 people, was broadcasted live by NHK. Asanuma began his speech by addressing the defense of sovereignty when he was unexpectedly attacked by a teenager wielding a short sword. The assailant, identified as Otoya Yamaguchi, leaped onto the stage and stabbed Asanuma twice in the chest, in front of thousands of viewers witnessing the shocking incident on live television. Asanuma suffered fatal injuries and was immediately rushed to the hospital. Sadly, he succumbed to his wounds and passed away at the age of 61.

A newspaper announcing Asanuma’s death

Yamaguchi, a 17-year-old member of the Uyoku Dantai associated with the Great Japan Patriotic party – a monarchist and traditionalist group – carried out the assassination. It is astonishing that Yamaguchi managed to evade security measures and approach Asanuma armed with a sword. The Great Japan Patriotic party, led by Bin Akao, held right-wing views and sensationally accused numerous individuals of being communists or seeking to dismantle the existing system in favor of an alternative one. Asanuma was falsely accused of harboring such intentions. It is important to note that the Great Japan Patriotic party, to which Yamaguchi belonged, had held pro-Anglo-American sentiments since the 1920s. Right-wing factions viewed any form of socialism as detrimental to Japan, regardless of nuanced distinctions. Additionally, it is noteworthy that the Yakuza, the Japanese organized crime syndicate, generally aligned with this group and were utilized by both Americans and the ruling Liberal Democratic party for acts of racketeering or assassinations targeting protesters and anti-American individuals. Following his arrest, Yamaguchi revealed no significant information during interrogations, and three weeks later, he was found dead in his jail cell, allegedly having taken his own life by hanging.

Inejiro Asanuma’s grave in Tama Cemetery, where Yukio Mishima is also buried

Conclusions

To grasp the essence of Asanuma's persona and his political path, it is critical to acknowledge his steadfast adherence to his historical convictions, anchored in a profound patriotic fervor. He never disavowed his allegiance to Emperor Hirohito or his connection with the Yokusankai. In stark contrast, Yamaguchi's life ended as a zealous devotee, a youthful warrior ensnared by the cultural sway of America. The repercussions of Yamaguchi’s deed echoed across the country, striking a chord especially with rightist factions, as such an overt and public act of political aggression had not been seen since the February 26th Incident.

Until his last days, Asanuma championed nationalism, showing unyielding reverence for the Emperor. Within the sorrowful tapestry of their tales, one can discern a thread of patriotism that linked Yamaguchi to Asanuma, despite their clashing political beliefs. The crux of their dissimilarity hinged on their positions in the Cold War landscape, with regard to America, the Soviet Union, or a stance of neutrality. Asanuma viewed the American presence as the chief threat, in contrast to Yamaguchi, who saw China and Korea as the foremost perils. In modern nationalist discourse in Japan, it is often opined that both Asanuma and Yamaguchi were men of staunch moral fiber, unshakable in their ideals and beliefs. The assassination still sparks debate, and while one might debate the honor of Yamaguchi's motives, the broader ramifications of his act on Japan cannot be overlooked, especially considering Asanuma's stature and the lost chance for a movement championing Japanese sovereignty.

In his era, Asanuma pressed for Japan to carve out an independent geopolitical identity, breaking free from American dominance. His untimely death, however, critically undermined the burgeoning movement for Japanese sovereignty. For those who value Japan’s geopolitical autonomy and imperial integrity, it becomes clear that Asanuma’s blend of National Socialism and opposition to American influence was arguably the most fitting strategy for the Cold War context. The detrimental aftermath of the American occupation, leading to Japan’s compliance, underscores the deep tragedy of Yamaguchi's well-meant but flawed action, a calamity unmatched in its implications for the Japanese nation and its ethos, akin to a soul-crushing act of self-destruction.

The assassination was a paradox of patriotism — where one patriot believed the killing of another was a necessity for Japan's destiny, both united by a deep-seated veneration for the Emperor. The event leaves a legacy of sorrow, akin to the pain of witnessing a relative cause harm to their own bloodline.

“My comrades, I think the essence of politics is to straighten the crooked things of the national society, to correct the wrong things, and to bring the unnatural things back to their natural form. However, there are many bent, fraudulent, and unnatural things in our country today.”

— Inejiro Asanuma's final speech at the Hibiya Public Hall Three-Party Leaders Speech on October 12, 1960