Introduction

The matter of race assumes a complex nature within the realm of Fascism. Its significance has infiltrated public discourse, as demonstrated by the recent statements of Paolo Di Canio, the esteemed Italian footballer, asserting that Fascism, as an ideology, does not inherently concern itself with race. Moreover, steadfast adherents of National Socialism contend that Fascism represents an anti-racial ideology, emphasizing that Fascist Italy only embraced racialist principles akin to those of Nazi Germany in 1938. Consequently, these observations provoke an inquiry into Mussolini's genuine position on race. I have frequently encountered individuals employing the following quote as evidence to suggest that Mussolini was purportedly devoid of racialist sentiments:

The credibility of this quote originates from the book Talks With Mussolini. This is a book authored by Emil Ludwig, it remains highly questionable when it comes to understanding Benito Mussolini's racial views. Despite the widespread dissemination of the statement attributed to Mussolini in this book, numerous scholars have raised doubts about the authenticity of the recorded conversations. Authors such as Christopher Duggan, Denis Mack Smith, E. R. Chamberlin, Richard Lamb, MacGregor Knox, Martin Blinkhorn, Richard J. B. Bosworth, and Stanley G. Payne have all expressed concerns about the accuracy and dependability of Talks With Mussolini. Throughout his career, Mussolini gave numerous interviews to both Italian and foreign journalists, many of which were published in his official newspaper, Il Popolo d'Italia. However, the book Talks With Mussolini was never acknowledged or published in Mussolini's newspaper because Ludwig did not accurately transcribe Mussolini's words. Despite Mussolini's efforts to prevent its publication, the book was released in Italy in 1932 under the title Colloqui con Mussolini.

The Fascist government ultimately banned the book, and Mussolini was angered by its existence, ordering its printing to cease immediately. The Press Office warned Italian newspapers three times to disregard Ludwig's book, except for the Fascist journal L'Impero, which criticized Ludwig and the publisher Arnoldo Mondadori as profiteers in an article published on June 18, 1932. The Italian Fascist press mostly remained silent on the matter to avoid drawing attention to Ludwig's book. Consequently, the book remained relatively obscure in Italy until its republication by Mondadori in 1950, after the war. Nevertheless, it garnered considerable attention in English-speaking countries and Germany. Journalists with National Socialist affiliations in post-war Germany reacted to the book's growing popularity and denounced it as a fabrication. Friedrich C. Willis, writing under the alias Georg Heinzmann, published an article titled Das Mussolini-Geschäft des Emil Ludwig Cohn in the Nationalsozialistischen Korrespondenz, unequivocally stating, "This does not represent our Mussolini!" Although discredited and banned, Talks With Mussolini continues to perpetuate a false narrative, circulating as if it were authentic. It's crucial to approach this source with caution and gain a comprehensive understanding of Mussolini's beliefs on race and anti-Semitism by exploring various sources and examining his expressed views over time.

There are arguments asserting that Fascism is disconnected from racism or anti-Semitism, using Mussolini's quote, "All within the state, nothing outside the state, nothing against the state," to bolster their claim. They interpret this as prioritizing the state over race and nation, deeming such considerations as irrelevant. However, understanding the true meaning of these concepts and Mussolini's quote requires considering the broader context of history, philosophy, and national character. Some argue that Mussolini held different views on race over the course of his career, demonstrating a lack of commitment to the idea and making him an opportunistic dictator. Academic studies such as Patterns of Prejudice and Why Mussolini Turned on The Jews by Franklin Hugh Adler, as well as The Jewish Question In Italy by Professor Herman De Vries De Hee-Keunge, easily dispel these arguments. I also have concerns about the substack article Italian Fascism and The Jews due to its lack of contextual understanding. While TIKHistory on YouTube presents similar arguments, a more thorough analysis uncovers an alternative narrative. This comprehensive examination aims to portray the true depiction of race culture during the era of Italian Fascism and its alignment with Mussolini's ideological framework.

Italian Fascism and The Jewish Question

In his article titled The Accomplices, which was published in Il Popolo d'Italia on June 4th, 1919, Benito Mussolini presented the viewpoint that the Bolshevik Revolution served as a manifestation of a Jewish vendetta against Christianity. He posited that this revolution was orchestrated by financial institutions with the intention of dismantling genuine socialism, paving the way for an international plutocracy dominated by Jewish world finance. Furthermore, Mussolini asserted that the Jews were leveraging Bolshevism as a foundation for a novel form of capitalism under the control of Anglo-Americans.

“If Petrograd (St. Petersburg) does not fall, if Denikin marks time, it is because the great Jewish bankers of London and New York so desire, linked up as they are by racial ties with the Jews who, in Moscow as in Budapest are taking revenge on the Aryan race which has condemned them to dispersion for so many centuries. In Russia 80% of the Soviet leaders are Jews. In Budapest 17 out of the 22 people's commissars are Jews. Might it not be that Bolshevism is the vendetta of Jewry against Christianity? It is a subject certainly worth pondering. It is entirely possible that Bolshevism will drown in the blood of a pogrom of catastrophic proportions. World finance is in the hands of the Jews. Whoever possesses the nations banks controls their politics. Behind the puppets of Paris stand the Rothschilds, the Warburgs, the Schiffs, the Guggenheims, who are of the same blood as the masters of St. Petersburg and Budapest. Race does not betray race. Bolshevism is defended by international plutocracy. That is the essential truth. International plutocracy, dominated and controlled by the Jews, has a supreme interest in hastening all of Russian life through its process of molecular disintegration to the point of paroxysm. A paralyzed Russia, disorganized and hungry, will tomorrow be the place where the bourgeoisie—yes the bourgeoisie, my dear proletarians—will celebrate its spectacular abundance. The kings of gold believe that Bolshevism must live now, to better prepare the ground for the new business of capitalism. American capitalism has already obtained a great "concession" in Russia. But there are still mines, springs, lands, workshops, which are waiting to be exploited by international capitalism.”

— Benito Mussolini, The Accomplices

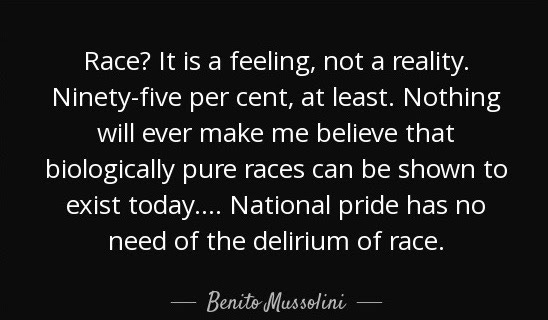

"Blame them" propaganda poster from Fascist Italy, 1944

Some argue that Mussolini couldn't have been strongly anti-Semitic because of his close ties to Italian Jews, so they bring up the fact that several early founders and members of the Fascist movement were Jewish. However In Religion or Nation? published in Il Popolo di Roma in 1928, Mussolini expresses confusion about the religious and racial nature of Jews. He believes this creates many contradictions between the Italian identity and the Zionist identity.

Mussolini says this:

“We then ask the Italian Jews: are you a religion or are you a nation? This question is not intended to give rise to anti-Semitic riots, but merely to bring to light a problem which I know exists, and which is useless to further ignore.”

— Benito Mussolini, Religion or Nation?

In his response to The Zionists, published in Il Popolo di Roma on December 16th, 1928, he clarifies his goals and true intentions regarding Jews. Mussolini argues that Jews who do not love Italy or who only love her for opportunistic reasons cannot be Italian. He points out that Jews are not in as many positions of authority in Italy as they are in Germany, meaning the Jewish question must be addressed differently relative to it’s circumstances. Mussolini even denounces Zionism as an international experience and as un-Italian. His intention was to provoke a clarification among Italian Jews and to open the eyes of Italians.

It ends with Mussolini saying that:

“A Jewish problem exists, and it is no longer confined to that shadowy sphere.”

— Benito Mussolini, The Zionists

In the book Mussolini: A New Life by Nicholas Farrell, the author says the following remarks about Mussolini and Jews:

“[Mussolini’s] hostility to Jews had an identical cause to his hostility to the bourgeoisie. It was the Jewish psyche or spirit, the epitome of the bourgeois spirit which he scorned as la vita comoda — that he wanted to stamp out, not the Jews.”

“Mussolini persuaded himself that the Jews, like the Freemasons, had secret loyalties which conflicted with Fascism. Judaism in general was international; it stood against the nation. Italian Zionists, in particular, who wanted to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine, also stood against the nation.”

— Nicholas Farrell, Mussolini: A New Life

Mussolini advocated for addressing the Jewish issue through measures involving cultural and racial assimilation, as well as mass deportations. This approach can be seen as relatively less extreme compared to the methods employed by the Nazis. Mussolini initially aimed to achieve gradual integration of Jews into Italian society, with the ultimate goal of eradicating their existence as a distinct group and assimilating them into the broader Italian identity. This perspective sheds light on Mussolini's collaboration with those Jews who prioritized Italy's interests and elucidates the presence of individuals like Margherita Sarfatti, who was partially of Jewish heritage and held a prominent position as Mussolini's main mistress until the 1930s. The diaries of Claretta Petacci, Mussolini's other mistress, were published by Italy's Corriere della Sera. The entries date back to 1938, a crucial year during Mussolini's Fascist regime due to the newly passed racial laws.

Mussolini said this to his mistress apparently.

"I have been a racist since 1921. I don't know how they can think I'm imitating Hitler, we must give Italians a sense of race.”

— Benito Mussolini, quoted in Claretta Petacci’s Diary.

Anti-British propaganda poster issued in Fascist Italy: “The principles of life and state of England Thirst for domination Exploitation False Devotion”, 1942

Mussolini also said in October 1938: "These disgusting Jews, I must destroy them all." According to the excerpts, Mussolini referred to Jews as "enemies" and "reptiles," indicating that he had developed a strong anti-Semitic sentiment in his later years. In Il Tevere, a Fascist newspaper founded by Mussolini and directed by Teresio Interlandi, frequently promoted anti-Semitism and warned of the perceived threat of international Jewry.

On December 30th, 1936, Mussolini stated that:

“The forerunner and justifier of anti-semitism is always and everywhere the same: the Jew, whenever he becomes overbearing, as he so often does.”

— Benito Mussolini, Too Much Is Crippling

Mussolini contends that anti-Semitism is a product of Jewish actions themselves. He notes the tendency in Germany to blame the Jews, but believes that it is the Jews themselves who provoke anti-Jewish sentiment. As an example, he highlights the names of Jewish individuals holding high-ranking positions in France, despite comprising only 2% of the population. Mussolini argues that this stark disproportion raises concerns.

Mussolini had no intention of establishing ghettos, inciting pogroms, or exterminating Jews. Instead, his approach involved discretely expelling Jews from Italy at a rate of ten individuals per day, temporarily aligning with the Zionist movement, similar to Hitler's stance. However, due to Italy's involvement in World War II, this plan was abandoned, and Jews were offered options for high-rate currency transactions. Consequently, only 6,000 Jews chose to leave, while the remaining Jewish population endured years of discrimination under the Fascist regime, with a significant number eventually being interned in concentration camps. The removal of Jews from public life did not indicate transformation; rather, it aimed to eliminate obstacles to Mussolini's fabricated vision of homogeneity, fulfilling the ideals of the Risorgimento.

As the historian Renzo De Felice notes:

“Mussolini's real 'obsession' was with the Italians. Out of a 'race of slaves,' he wanted to create a 'race of lords.'”

— Renzo De Felice, Mussolini

Benito Mussolini in Rome, 1940

Mussolini's efforts to strengthen the standing of Catholicism as Italy's dominant religious faith began to damage the equality and autonomy of Judaism in Italian society soon after he rose to power in 1922. The 1934 campaign of the Rome-based Fascist newspaper Il Tevere against Jews for supposedly being unassimilable and lacking a fully-fledged allegiance to Italy was also pointed out by Luc Nemeth. Michele Sarfatti showed that Mussolini's plans to protect the Italian race started in 1927, six years before Adolf Hitler became Führer, at a time when Mussolini had no German ally to please, and when the NSDAP was still a minor political party. Against this backdrop, the Nazi influence on the racial policy of Fascism becomes reduced, and Italian anti-Semitism acquires its own native character. Mussolini also denounced Pope Pius XI, who saw the rise of anti-Semitism in the late 1930s as being harmful to the Catholic Church. Pius commissioned an encyclical to denounce racism and German nationalism, but it was never published due to his death. Mussolini accused Pius XI of doing "undignified things, such as saying we are similar to the Semites."

According to Sarfatti, in 1936, ordinary people stigmatized the racial origins of several Jewish Fascist leaders, such as Renzo Ravenna, the local mayor of Ferrara, to call for their dismissal. This offers additional evidence of the extent of grassroots anti-Semitism in Italy. Three years earlier, the appointment of another Jew, Enrico Paolo Salem, as mayor of Trieste, was criticized in similar anti-Semitic terms. A failed attempt on Mussolini's life in Bologna on October 31, 1926, also provoked an assault on Padua's synagogue by Fascist squads, and anti-Jewish tirades were commonplace in L'Impero and other Fascist newspapers during that year. Moreover, the publication of a 1959 private exchange of letters between two prominent Italian historians, Federico Chabod and Arnaldo Momigliano, revealed that the latter identified a few instances of Mussolini's discrimination against Jewish intellectuals on racial grounds as early as 1933.

Pre-1938 Fascist anti-Semitism included Alessandro Della Seta, a Jewish archaeologist. Della Seta was barred from the Accademia d'Italia twice, in 1932 and 1933, although he ranked first for his subject both times in the competition for admission. In the early 1930s, the president of that body, Nobel prizewinner Guglielmo Marconi, following Mussolini's orders, made a point of identifying those scholars among the candidates who were Jewish; none was ever accepted for membership. But the specific rejection of Della Seta's candidacy is a revealing example of pre-1938 Fascist anti-Jewish attitudes. In the spring of 1932, Mussolini himself pointed to the archaeologist's forthcoming admission to the Accademia d'Italia as the undisputable proof that "anti-Semitism does not exist in Italy." Therefore, Della Seta's eventual exclusion was a clear refutation of the supposed racial tolerance of Fascism. In addition, Joel Blatt has shown that the large Jewish membership of Turin's anti-fascist organization Giustizia e Libertà sparked an initial, though short-lived, anti-Semitism campaign as early as 1934.

This provides further evidence that anti-Semitism was active in Italy long before it was openly expressed in 1938. Mussolini not only tolerated it but encouraged it. Hostility towards Jews was so pronounced even before the enactment of racial laws that it was used to advocate changes within the Fascist hierarchy itself, as was the case with Renzo Ravenna and Enrico Paolo Salem. As a consequence of these findings, both the notion of prevailing racial tolerance in Italy and the hypothesis of anti-Semitism as a belated German import, which had long provided scholars with the grounds for positing an alleged Italian sympathy with Jews, have turned out to be groundless.

While Mussolini may not have directly ordered the killing of Jews, his actions encompassed what can be classified as cultural genocide according to the United Nations' own definition. By 1942, the majority of Cyrenican Jews were interned in a concentration camp located in Giado, where approximately one-fifth of them succumbed to starvation, exhaustion, and typhus. Jewish lives in Sidi Azaz and other smaller camps established by the Italians in Libya were further claimed by diseases, harsh labor conditions, and mistreatment. Additionally, a few hundred Italian Jews deemed a threat to national security were interned in concentration camps in Italy as soon as Mussolini entered the war in June 1940.

The existence of the largest concentration camp in Calabria, Italy, challenges the notion that the persecution of Jews began only after September 8th, 1943, when the Nazis assumed control following the armistice with the Allies. Deportations from territories under Italian rule commenced prior to Nazi takeover, indicating active collaboration by the Italians. Furthermore, Giuseppe Mayda has extensively documented the spontaneous complicity of Fascists with Nazi occupiers, as well as autonomous initiatives by Italians in the persecution of Jews after the establishment of the Social Republic. Liliana Picciotto Fargion argued that at least 27% of deportees from Italy and the Dodecanese after the establishment of the Social Republic were arrested by Italians acting independently, with an additional 4% arrested by Italians with German assistance. Fargion emphasizes that Italians played an active role in the persecution and deportation of Jews, particularly between December 1943 and mid-February 1944, when they managed the Jewish Question through legislation and arrests. During this period, the Italian Social Republic established and operated the Fossoli concentration camp near Carpi, Italy, as a temporary internment facility for Jews prior to their deportation to German camps. The camp was opened on December 5th, 1943, and was subsequently taken over by Nazi authorities on March 15th, 1944. Furthermore, officials of the Italian Social Republic seized the properties of Jews in Florence and personally profited from the sale of these assets.

Under the Fascist regime, an estimated one million casualties occurred, predominantly in African colonies. In Italy itself, a significant number of victims were claimed under the Social Republic, including partisans, civilians, and Jews. While it is challenging to provide an exact estimate, consensus suggests that the death toll ranges between 10,000 to 30,000. Even in the final months of the Social Republic, members of the Fascist government rejected diplomatic offers that would have granted some leniency to Jews in exchange for post-war benefits. While comparing figures may not be the most effective means of assessing culpability or drawing comparisons between Italy and Germany, it does further challenge the prevailing perception of Italian anti-racism and benevolence. Patrizia Dogliani's book, Italy Under Fascism, suggests that the fate of Jews in Italy might have been even worse had Mussolini's regime not fallen in July 1943. Fascist authorities had plans to intern all Jews between the ages of 18 and 36 years. Eventually moving them from Italian camps to Nazi concentration camps.

Italian Fascist anti-Semitic propaganda poster, 1942

The Italian Fascist View on Race

In Is The White Race Dying? published in Il Popolo d'Italia on September 4th, 1934, Mussolini predicted a decline in racial demographics, echoing the rhetoric of many racially-conscious nationalists today. He referred to it as a civilizational crisis affecting all of European civilization.

Mussolini says this:

“However, for Italy — as well as for other countries inhabited by people of the White race — it is a matter of life or death. It is a matter of knowing whether the civilization of the white man is destined to perish in the face of the growing number of yellow and black races.”

— Benito Mussolini, Is The White Race Dying?

Mussolini was concerned that the increasing numbers and geographical expansion of Asian and African races would cause the civilization of Europe to decline. He argued that he had been warning people about the decline of the "White Race" since 1926, which is why he launched the Battle for Births in 1927 to encourage women to have children. Tax privileges were given to families with more children, while bachelors faced high taxation. On the issue of the low birth rate of White people, Mussolini said in 1928:

“[When the] city dies, the nation – deprived of the young life-blood of new generations – is now made up of people who are old and degenerate and cannot defend itself against a younger people which launches an attack on the now unguarded frontiers [...] This will happen, and not just to cities and nations, but on an infinitely greater scale: the whole White race, the Western race can be submerged by other coloured races which are multiplying at a rate unknown in our race."

— Benito Mussolini quoted in Fascism by Roger Griffin

“We are moving towards an Africanized America in which the white race, due to the inexorable law of numbers, will end up being overwhelmed by the fertile nephews of the proverbial Uncle Tom. Will we see blacks in the White House in half a century, in a century?”

— Benito Mussolini, Europe Without Europeans

It is essential to note that these statements were made by Mussolini prior to his establishment of a close association with Hitler. These remarks took place around 1934, a period characterized by strained relations between Germany and Italy, as tensions escalated following the assassination of Austrian Fascist dictator Engelbert Dollfuß, which carried the potential risk of war. Mussolini also referred to a “White race” in Which Way Is The World Going? published in Gerarchia on February 25th, 1922, indicating that he at the very least recognized the existence of race. So I find it hard to believe Mussolini got these views from Hitler. Further validation of this can be found various quotations from Mussolini talking of race. Where we see an obvious continuity in early Fascism to its more mature views during the 1940s.

“In the first place she (the Italian nation) has a sure foundation, and that is the vitality of our race.”

— Benito Mussolini speech in Trieste, September 20, 1920

“I have an unbounded faith in the future greatness of the Italian people. Ours is, among the European peoples, the largest and most homogeneous. Unlike the pessimists who believe that everything is great in other people’s houses, while everything is too small in their own, we have pride in our race and our history.”

— Benito Mussolini speech in Trieste, February 6, 1921

“How then was this Fascismo born... it was born of the profound and perennial need of this our Mediterranean and Aryan race...”

— Benito Mussolini speech in Bologna, April 3, 1921

“We feel those bonds of race to be alive and vital which bind us, not only to the Italians of Zara, Ragusa and Cattaro, but also to those of the Canton Ticino and Corsica, to those beyond the oceans, to all that great family of fifty million men whom we wish to unite in the same pride of race.”

— Benito Mussolini speech in Bologna, April 3, 1921

“Italy is not a State, she is a nation, because from the Alps to Sicily there is the fundamental unity of our race, our customs, our language and our religion.”

— Benito Mussolini speech in Milan, October 4, 1922

“It must not be forgotten that, besides the minority that represent actual militant politics, there are forty millions of excellent Italians who work, by their splendid birth-rate perpetuate our race...”

— Benito Mussolini speech Delivered in the Chamber, November 16, 1922

“We, here and everywhere, are ready for any battle so that we may uphold the foundations of our race and of our history.”

— Benito Mussolini speech in London, December 12, 1922

“Let me first of all say how happy I am that we should have met in these magnificent rooms which furnish evidence of the strength and beauty of our race.”

— Benito Mussolini speech in Rome, January 2, 1923

“It is obvious that the problem of Italian expansion in the world is a problem of life or death for the Italian race.”

— Benito Mussolini speech in Milan, March 30, 1923

“I have looked you well in the face, I have recognized that you are superb shoots of this Italian race which was great when other people were not born, of this Italian race which three times gave our civilization to the barbarian world, of this Italian race which we wish to mold by all the struggles necessary for discipline, for work, for faith.”

— Benito Mussolini speech in Sassari, June 10, 1923

“Fascism, representing an irresistible movement for the regeneration of the race, was bound to carry with it this island where the Italian race is manifested so superbly.”

— Benito Mussolini speech in Cagliari, June 12, 1923

“Rome is always, as it will be tomorrow and in the centuries to come, the living heart of our race!”

— Benito Mussolini speech in Rome, June 25, 1923

“It is therefore necessary to take great care of the future of the race, starting with measures to look after the health of mothers and infants.”

— Benito Mussolini speech of the Ascension, May 26, 1927

“Peace with honor and justice is a Pax Romana... a peace in conformity with the character and temperament of our Latin and Mediterranean race which I wish to exalt before you because it is the race which has given to the world, among thousands of others, Caesar, Dante, Michelangelo, and Napoleon; a race of creators and constructors, ancient and strong, determined and universal, which has given the keynote to the world three times in the course of the centuries.”

— Benito Mussolini speech in Florence, October 23, 1933

“This is why the racial laws of the empire will be rigorously observed and that all who sin against them will be expelled, punished, imprisoned. Because for the empire to be preserved the natives must be clearly and forcefully aware of our superiority.”

— Benito Mussolini speech in Rome, October 25, 1938

“Our rural policy follows this course...to preserve and pass on the intrinsic virtues of the Italian race...”

— Benito Mussolini speech at the Argentina Theatre in Rome, January 22, 1939

“Our capacity to recuperate in moral and material fields is really formidable and constitutes one of the peculiar characteristics of our race.”

— Benito Mussolini speech to the Blackshirts of Rome, February 23, 1941

Italian anti-American propaganda poster. The freedom of the liberators! Italy, 1944

In the 1920s, Italian Fascists targeted Yugoslavs, especially Serbs, accusing them of having "atavistic impulses" and conspiring together on behalf of the Grand Orient of Masonry. They claimed that Serbs were part of a "social-democratic, masonic Jewish internationalist plot." Benito Mussolini viewed the Slavic race as barbaric and identified the Yugoslavs as a threat to Italy, ultimately claiming that the rivalry over the region of Dalmatia rallied Italians together at the end of 1st World War. These claims often emphasized the "foreignness" of the Yugoslavs as newcomers to the area, unlike the ancient Italians, whose territories the Slavs occupied.

Mussolini has even made genocidal statements regarding Slavs:

“When dealing with such a race as Slavic—inferior and barbarian—we must not pursue the carrot, but the stick policy. We should not be afraid of new victims. The Italian border should run across the Brenner Pass, Monte Nevoso and the Dinaric Alps. I would say we can easily sacrifice 500,000 barbaric Slavs for 50,000 Italians.”

— Benito Mussolini, speech in Pula September 20, 1920

Italian soldiers burning a village in Čabar in the Independent State of Croatia in 1941

The Ethiopian invasion was seen as an opportunity to address the situation discussed in Mussolini's 1934 essay. He pushed for demographic colonization, which involved creating permanent Italian settlements to solve Italy's land hunger problem and repopulating East Africa as a white European space. Maintaining racial boundaries was central to Mussolini's colonial culture vision. This motivated many in the Fascist party to serve the regime, and architects and urban planners used race as the main criterion for spatial organization in Ethiopia. They followed the mandates to keep Italian and African cultures separate and unequal, passing laws in 1939 with the goal of preserving "racial prestige." These laws regulated interracial social contact and enforced racial segregation.

Benito Mussolini on a visit to inspect Italian troops in a North African battle zone, 1942

In 1937, miscegenation became a criminal offense for all Italians, punishable by five years in prison. Women who had relationships with African men were publicly whipped and sent to concentration camps. Many Italian colonial authorities and some party members believed that assimilation similar to the French model led to the loss of white prestige by encouraging the colonized to mimic their European rulers. Instead, they advocated for a politics of difference that would continually remind Africans of their inferior status.

"In addition, a system of apartheid was introduced involving segregation in public places and an April 1937 law made sexual relations between whites and blacks a crime punishable by up to five years in prison. A popular Fascist song was ‘Faccetta nera’ (Little Black Face) about a slave girl freed by Italian soldiers so she can go to Rome and wear a black shirt. Eventually, Mussolini banned the song and ordered Badoglio to punish Italian soldiers guilty of “sexual relations with native girls."

— Nicholas Farrel, Mussolini: A New Life

Additionally, the Italians displayed favoritism towards non-Christian groups by granting autonomy and rights to Oromos, Somalis, and other Muslims, many of whom had supported the invasion. Further information about Italian colonies can be found in the book Italo Balbo: A Fascist Life. Mussolini abolished slavery in Ethiopia during the occupation but approved of war crimes and human rights violations against the civilian population. Italy used mustard gas during the invasion, forced labor, intentional targeting of civilians under Mussolini's orders (documented in public Italian archives), and even committed massacres during the occupation.

Italian soldiers with a mustard gas bomb

Footage of the gassing

It is important to acknowledge that the deployment of mustard gas during the invasion was employed sparingly and in response to initial misconduct by the Ethiopians, who utilized dumdum bullets and engaged in cruel rituals involving the execution of Italian soldiers. As observed by Farrell in his work Mussolini: A New Life, the usage of mustard gas had minimal impact on the overall outcome of the conflict. The swift downfall of the Ethiopian government and the subsequent period of looting in the capital towards the end of the war can be attributed to the Italian army's superior strength and the inadequate military strategies employed by the Ethiopians.

Following the rise of Fascism and the subsequent improvements in Italy, numerous Italians who had previously emigrated started returning to their homeland. In 1913, the number of Italians living abroad reached 900 thousand, but by 1925, it decreased to 320 thousand. In 1926, the number further dropped to 280 thousand, and in the same year, approximately 150 thousand Italians made the decision to return to Italy. When Italy was focused on resettling its population in its colonies, it came under the administration of Italo Balbo.

“He favored those Libyans whom he thought best fitted into the Italian scheme of things. The peoples of the coastal regions he admired because he regarded them as “superior races influenced by Mediterranean civilization” and capable of absorbing the new fascist values and institutions. The Negroid peoples of the Fezzan, he concluded, were not at that level and must be left to their own devices under military rule.

He was also very strict when matters of European “prestige” were at stake. Two Libyans, accused of having “touched” an Italian woman in the street, were sentenced to eight years in prison for having “violated racial prestige.” Foreign journalists remarked on the excessive formal respect the Italians demanded from Libyans. An English traveler commented, “The natives are browbeaten as nowhere else in North Africa,” and noted the “embarrassing obsequiousness” of the Libyans. Even in the most remote oases, they “snap and quiver to attention” as soon as a European appears. In Tripoli, bootblacks gave the fascist salute and bellowed “Evviva il Re-Imperatore, evviva Mussolini, evviva l’Italia,” before they grabbed a customer’s shoes.

Yet European visitors also remarked that under Balbo, Italians in some ways treated Libyans with a surprising informality and ease that was not typical of European colonial regimes. Italians thought nothing of working side by side in the fields with Libyans; Italian officials greeted Libyan notables with great cordiality and friendliness. There was little discrimination in the use of public facilities. Libyans could stay in any hotel and could travel first class on public transport whenever they could afford it. A paternalistic and Arabophobe Frenchman, travelling in Libya in 1938, remarked that the Libyans were no less well cared for than Europeans. In Libya, at least, he remarked, he did not feel the need for a “thorough cleaning up” of the Arab population as he did in Tunisia.

The “little citizenship” amounted to a token reward to Moslem Libyans who had served in Ethiopia. The measure was also intended to create an elite favorable to the Italians. Qualified Libyans could now acquire certain rights and privileges – mainly that of joining fascist organizations for Libyans – without losing their family and inheritance rights under Moslem law. Under the “little citizenship” Libyans could pursue a military career in Libyan units; serve as podesta (mayor) of an Arab community – but not a mixed one; serve in public office within the corporative system; and join the Associazione Musulmana del Littorio, the party organization for Libyans. But in return for this “special citizenship,” a Libyan had to renounce his right to apply for metropolitan citizenship. Moreover, the “special citizenship” was valid only in Libya. This guaranteed that there would be no “immission of Arab elements into the peninsula,” noted Padano.”

— Claudio G. Segre, Italo Balbo: A Fascist Life

Prior to their arrival, geologists, agronomists, and ethnologists conducted preliminary surveys to identify optimal locations for towns and farms. Colonial scientists even drew up plans for a demographic colonization. The aim of this settlement policy was to boost Italy's birth rate and counter the rural exodus to urban areas within the country. However, the underlying motive of these plans was overtly eugenic, intended to "enhance" the Italian populace and increase birth rates. In 1938, approximately 20,000 colonists were sent to Libya amidst great excitement, accompanied by the German Labor Attaché. By 1940, the number of colonists had reached 40,000. When Britain and France assumed control of Italy's Libyan colonies in 1943, there were approximately 150,000 Italians residing in North Africa. These examples serve to emphasize the evident racial awareness within Italian Fascism, which prioritized European racial superiority while still providing what they perceived as fair treatment to their racially subordinate subjects. This distinction is evident in Balbo's contrasting portrayal of Libyans and negroes. Additionally, the policy of "little citizenship" further demonstrates the unequal treatment between ethnic Italians and the indigenous populations of Italian colonies within Italy itself.

In Race and Faith: The Catholic Church, Clerical Fascism, and The Shaping of Italian anti-Semitism and Racism by Nina Valbousquet, it is discussed how the Catholic Church held a specific perspective on miscegenation during the Fascist era. According to Msgr Francesco Borgongini Duca, the Nuncio to the Italian government at that time, the Church discouraged unions between whites and blacks, as well as any form of heterogeneous unions. The Church justified this stance on moral and hygienic grounds, aiming to prevent the birth of mixed-race individuals who, in their view, would inherit perceived flaws from the different races involved. This viewpoint was summarized in a draft written by Msgr Domenico Tardini, the secretary of the Congregation of Extraordinary Ecclesiastic Affairs, which emphasized the Church's role in dissuading such unions due to the potential for unfavorable outcomes. These details can be found in the Archivio Segreto Vaticano, specifically the Nunziatura Italia, in b. 9 and f. 5.

In Germany, there was a notable interest in the Italian initiatives aimed at providing material support to families, comprehensive care for mothers and children, and settlement policies for expanding Italy's presence in Northern and Eastern Africa. The Germans also took keen notice of Italy's intentions to exclude and suppress individuals deemed "undesirable" within the population. In the 1920s, Italy developed a robust system of persecution, which the regime sought to utilize in order to create a unified and racially homogeneous society. However, German interest extended beyond these aspects and was primarily focused on the racial ideology that underpinned Italian Fascism as a whole. An article titled Italian Racal Protection, published in 1927 in the Völkischer Beobachter, the central ideological publication of the emerging National Socialist movement, is indicative in this regard. The article asserted that Italy, in stark contrast to the Weimar Republic, had implemented a comprehensive framework of Fascist laws for the "protection of the race," which greatly intrigued the National Socialist movement. The piece not only highlighted "positive" eugenic measures, such as support for mothers and children, which were purported to enhance the purity, health, and cleanliness of the Fascist society, but also praised repressive measures. It discussed various aspects, including Italian policies on abortion that involved punitive actions against women and doctors, along with severe prison sentences. The article contended that such measures would strengthen the German people, and advocated for the adoption of a similarly comprehensive policy for national rejuvenation in Germany.

Upon examination, it becomes apparent that Hitler was imitating Italian Fascism. In 1933, The Illustrated London News made a noteworthy observation, stating that "Hitlerism resembles Fascism and was, in fact, borrowed from Fascism." Hitler himself promoted the notion early on that National Socialism was entirely separate from Italy, reiterating this perspective consistently in subsequent years. This historical context enables us to better comprehend the true significance of the National Socialist rhetoric of singularity. It was a calculated effort, starting in 1933, to disassociate National Socialism from Italian Fascism at the ideological level and to redefine the Third Reich in terms of racism and anti-Semitism as something distinct, extraordinary, and unprecedented.

Anti-Semitism became the central and defining tenet of National Socialist ideology. While there were indeed variations in the racist and anti-Semitic positions held by the two dictatorships, the National Socialist regime intentionally magnified the disparities between Italy and Germany to create an exaggerated perception of their divergence. The German regime began to criticize Italy's seemingly lenient stance towards Jews. An additional set of circumstances lent further credence to the thesis that the ideological gap between National Socialism and Fascism was often the result of a deliberately fabricated alterity.

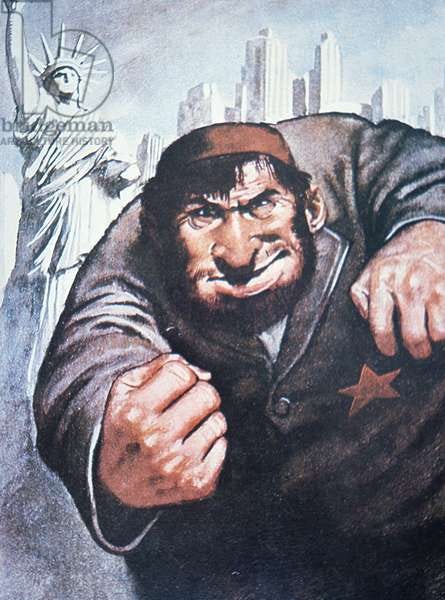

Racist anti-American Fascist propaganda poster 1944

These apparent distinctions played a significant role when the two regimes briefly adopted a confrontational approach following the assassination of Engelbert Dollfuß in July 1934. Racism was emphasized as a point of divergence between the regimes. However, it is evident that this dispute did not stem from profound ideological distinctions, but rather from power rivalries and the National Socialists' need to establish a distinct identity for themselves. Ultimately, this rhetoric of differentiation can only be understood in the context of the widespread accusations of plagiarism leveled against National Socialism during that period. Both in Germany and internationally, the prevailing sentiment was that Hitler and his movement were mere imitations of Italian Fascism, lacking originality and depth.

The Nazis' conception of Volksgemeinschaft, engendering a profound reconfiguration of identity, accentuating the primacy of the folk-community predicated on shared lineage, linguistic affinity, and cultural heritage. This harmonious union encompassed the entirety of the German populace, transcending geographical boundaries and situating itself at the core of National Socialist ideology that amalgamated the nation and the state. The economic decisions of individuals were inextricably tied to their fidelity and subservience to the collective will of the Volk, embodied by the Führer through the Führerprinzip. Intriguingly, Italian Fascism, in parallel, underscored the perpetuity of race and blood as indelible facets throughout historical epochs, a notion explicitly elucidated in the fourth point of The Fascist Decalogue.

“The genius of a race reborn, of Latin tradition, unchangingly active in our thousands of years old history, a return to the Roman and simultaneously Christian idea of state, a synthesis of the great past with a radiant future.”

— The Fascist Decalogue

Both movements shared a broader focus on the collective identity encompassing language, culture, and heritage, the concurrence of Fascist tenets in the Nazi ideology indicates a heavy influence from Italian Fascism, particularly with regard to the formulation of the folk-community, discernible in the inaugural First Fascist Congress convened in Milan on the 23rd of March 1919.

“We cannot remain deaf to the struggle for Fiume, we deeply feel the living nature of the ties that bind us not only with the Italians of Zara, Ragusa, Cattaro, but also with the Italians of Ticino, even with those Italians that do not wish to be Italian – with the Italians of Corsica, Italians living across the ocean, with that huge family that we wish to unite under the aegis of common racial pride.”

— Benito Mussolini, First Fascist Congress, Milan March 23, 1919

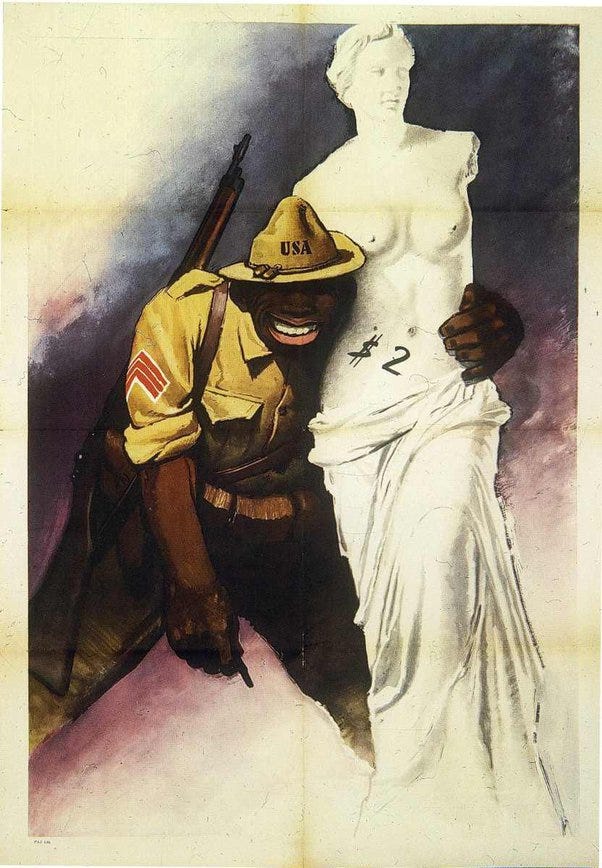

A racist propaganda poster in 1944 showing an African-American solder selling the Venus de Milo for $2.00

Initially, Mussolini viewed Nazism with contempt because it advocated for the "Theory of Nordicism." However, it should be recognized that Hans Günther’s vulgar Nordicist beliefs were not the dominant ideology within the Nazi party. Over time, Mussolini publicly criticized National Socialism as a barbaric ideology rooted in Nordic myths. However, according to A. James Gregor's publication, National Socialism and Race, the Nazis eventually distanced themselves from extreme Nordicism, adopting a more inclusive notion of a developing German race. This change stemmed from the understanding that Germans were not a pure race, but a blend of various sub-racial groups, with the Nordic element being most prominent and considered the ideal for the German people. Within the NSDAP, this perspective emerged as early as 1933, with proponents such as Friedrich Merkenschlager, and was later endorsed by figures like von Eickstedt and Dr. Walter Groß.

Mussolini denouncing the anti-Italian sentiment of Nordicism

The same tendencies were observed in Italy with the Fascist Manifesto of Race in 1938 and the works of Maggiore and Franzi. The concept was no longer limited to fixed, pure, and immutable races, but rather was focused on races in formation. The components of these races arise from the crucible of past races, and are shaped by the ideal of a living heritage in an Aryanism of favorable characteristics.

A. James Gregor says this:

“In effect this last phase of National Socialist race theory was a complete rejection of Guenther's Nordicism. The Mongolian Race was restored as the creator of Asiatic culture and the Mediterranean Race was once more spoken of as the creator of the high culture of the ancient Mediterranean."Almost all" of classical art was no longer conceived of as Nordic but as Mediterranean.”

— A. James Gregor, National Socialism and Race

Italian Fascism, in blending the idea of race into its dogma, aimed to converse with contemporary intellectual currents. Nevertheless, key Fascist thinkers like Giovanni Gentile found this notion distasteful and at odds with his philosophical principles, dismissing it for its materialistic underpinnings in Biology, which he deemed unacceptable.

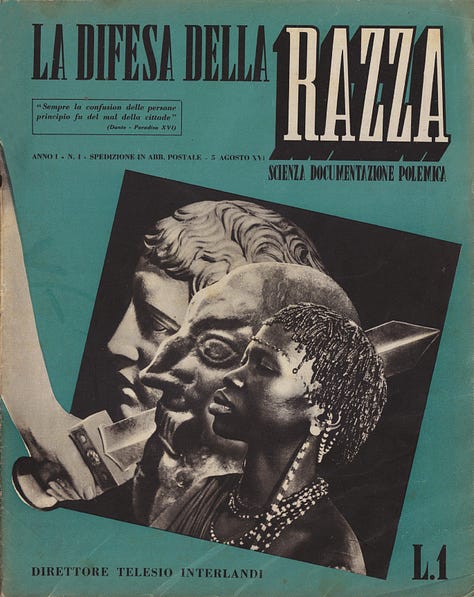

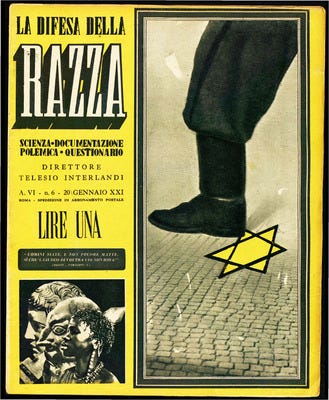

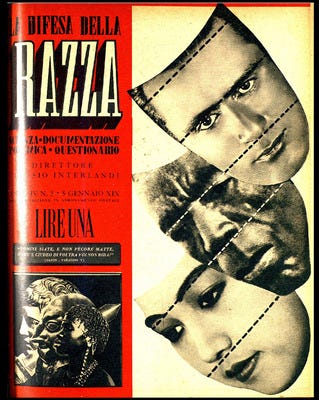

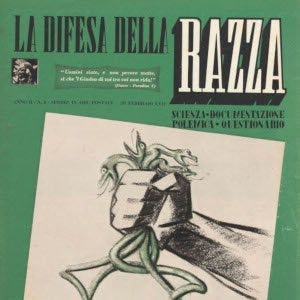

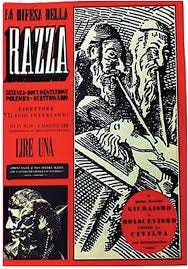

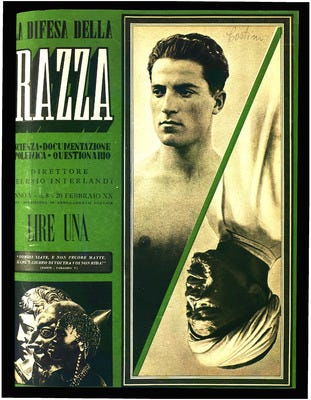

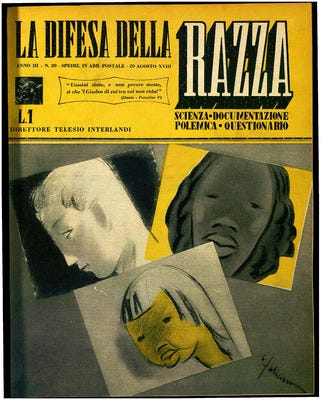

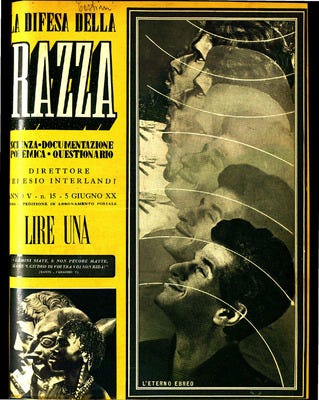

The Defense of The Race magazine, published from 5 August 1938 to 20 June 1943

Despite this, the philosophical framework Gentile devised for Fascism was flexible enough to be adapted to racial considerations. For instance, just as the laws of physics and chemistry achieve consistency in reality through the construct of an infinite mind, so too can the principles of heredity find order within the collective reality. Niccolò Giani, a distinguished Fascist intellectual, contended that Hegel's perspectives on race could be assimilated into Fascist Actualism. He saw this not as a paradox but as a dialectical evolution within Fascist thought.

Hegel himself made a statement on this matter in The Philosophy of History:

"The peculiarly characteristic feature of the Negro is that his consciousness has not yet attained to the realization of any substantial objectivity, as for example, that of God or law; and hence his nature is one of mere wild, brutal caprice. On the other hand, the Negro exhibits the natural man in his completely wild and untamed state. We must lay aside all thought of reverence and morality—all that we call feeling—if we would rightly comprehend him; there is nothing harmonious with humanity to be found in this type of character. The copious and circumstantial accounts of missionaries completely confirm this, and Mahommedanism (which first proceeded from Arabia to the West coast of Africa, and from thence to other parts) has, like Christianity, been able to do very little towards improving the moral condition of the Negroes."

— Hegel, The Philosophy of History

Giani's interpretation of Hegel's philosophy allowed for it to be woven into the fabric of Fascist Actualism, justifying racial discrimination. By leveraging Hegel's assessments of African consciousness — which suggested a lack of self-awareness and capacity for abstract thought — these ideas were used to argue the inherent superiority or inferiority of certain races, bolstering the Fascist intellectuals' view of Italian racial superiority. The notion of race is dynamic and ever-evolving, influencing the continuous transformation of history. A. James Gregor posited that Italy's enactment of "Race Laws" was primarily a concession to Hitler. Yet, it can also be viewed as a natural extension of Fascist ideology, independent of Mussolini's private convictions and reflecting a broader philosophical progression within the movement. His statement in The Irrefutable Fact in Il Popolo d'Italia, July 31st, 1935, adds to this understanding of race.

Musollini writes:

“We Fascists acknowledge the existence of races, their differences and their hierarchy. But this does not mean that we present ourselves to the world as the embodiment of the White race in a war against other races; and we do not intend to make ourselves the preachers of exclusivism and racial hatred.”

— Benito Mussolini, The Irrefutable Fact

The creation of the Fascist Manifesto of Race on July 26, 1938, marked a significant moment in history, crafted by a collective of Fascist academics from Italian universities and backed by the Ministry of Popular Culture. This document established the core principles of Fascist racial theory and garnered the signatures of 180 individuals, among them were two physicians, S. Visco and N. Fende, an anthropologist, L. Cipriani, a zoologist, E. Zavattari, and a statistician, F. Savorgnan.

The 10 points of the Fascist Manifesto of Race, in summary says this:

Human races are a reality.

Races can be classified into large and small categories.

Race is a concept that is purely biological.

The majority of the current population of Italy is of Aryan origin and its civilization is Aryan.

The idea that large masses of people migrated to Italy in historical times is a myth.

The Italian race already exists.

Italians must declare themselves as racialists.

It is necessary to distinguish between Mediterraneans from Europe, and Orientals and Africans.

Jews do not belong to the Italian race.

The purely European physical and psychological characteristics of Italians must not be altered in any way.

Front page of the Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera on 11 November 1938: "The laws for the defense of race approved by the Council of Ministers.”

Julius Evola was instrumental in forging ties between Italian and German Third Positionism. To fully grasp Mussolini's views on race, one can turn to Evola's extensive writings on the matter. Although Evola criticized Fascism for not being sufficiently radical, Mussolini relied on him to craft the official Fascist racial doctrine. Evola's doctrine was rooted in a tripartite racial concept, including the physical (Body), the psychological (Mind), and the spiritual (Spirit). Evola promoted the idea of Italian racial superiority and encouraged the Fascist regime to foster the growth of a “new Italian man,” epitomizing the race's most exemplary traits. In his framework, the Body was the foundation of racial identity, shaping physical attributes; the Mind dealt with intellectual and psychological traits; and the Spirit related to the cultural and spiritual dimensions of race. Overall, the official stance of Fascism regarding race can be summarized as follows:

"A relationship of absolutely pure blood connects today's Italians with the generations that have lived in Italy for millennia. This ancient purity of blood is the greatest title of nobility of the Italian nation... The purely European character of Italians would be altered by any crossing with a non-European race, bearer of a civilization different from the millennia-old civilization of the Aryans."

— The Second Book of Fascism

Mussolini speech on racial prestige and Empire

Conclusions

Italian Fascism was deeply entrenched in a racial ideology that emphasized the preservation of blood purity and the cultivation of a superior Italian race. While there might have been differing opinions among intellectuals, the presence of racial consciousness within Fascism was integral and naturally evolved. This racial emphasis primarily revolved around the prestige of European races, firmly rejecting the concept of equality between Italians and individuals of other races. Although it is conceivable for Fascism to exist without a racial component, as illustrated by the views of Giovanni Gentile, it is crucial to acknowledge that prominent figures like Giuseppe Bottai believed that the "Fascist Revolution" would remain incomplete without a racist and anti-Semitic character. Therefore, it is vital to recognize that Italian Fascism inherently possessed a racial consciousness that developed organically. Dismissing this reality would undermine a comprehensive understanding of Fascism's true intentions.

While it is true that some Jews initially expressed support for Fascism, it is imperative to recognize that Mussolini and his intellectual circle were unabashedly racist and anti-Semitic. Furthermore, grassroots support for these ideas emerged spontaneously within the Fascist movement. It is impossible to overlook the fact that this trajectory ultimately led to the persecution and deportation of 15% of the Italian Jewish population to Auschwitz. Jews who collaborated with Fascism renounced their Jewish identity and were subsequently disassociated from the Jewish community. This represented the Italian understanding of the "Jewish Question" and the framing subsequently adopted by Mussolini.

Italy established explicit racial hierarchies in its colonies, and the Conference of Montreux (the Fascist Internationale) welcomed parties espousing anti-Semitic and racist beliefs, such as the Iron Guard and the Greek National Socialist party. This serves as an indication of Mussolini's affinity for groups associated with such ideologies. Claims suggesting otherwise are propagated by revisionists or those lacking a comprehensive understanding of history. Over a span of several years, Hitler and his associates actively pursued alignment with Mussolini's regime in matters pertaining to racist policies. Italy served as a compelling model in internal discussions concerning the establishment, consolidation, and advancement of the German dictatorship. The two regimes collaborated internationally in the persecution of their adversaries and marginalized groups, with vital cross-border learning processes significantly bolstering the German regime. Consequently, the Nazis' portrayal of themselves as independent and detached from external influences is exposed as fallacious.

It is crucial to acknowledge that Fascism and National Socialism are inseparable, as Fascism itself was undeniably racist and anti-Semitic. Mussolini, the leader of Fascism, held these views, which gradually transformed into official policies of the Italian government independent of German influence. If anything, it was the Germans who emulated Italian Fascism with regard to this matter. Moreover, Fascism committed its own atrocities during wartime, tarnishing its reputation. Interpretations of Italy's resistance against Nazism have been influenced by political motives, seeking to delegitimize genuine Fascist supporters while attempting to rehabilitate Fascism's public image. This firmly rebukes the notion of the "good Italian" within academic circles as a myth.

These publications offer further insight into the Fascist ideology on race and anti-Semitism:

Catholics and Racialism by Giulio de' Rossi dell'Arno, published in La Rassegna nazionale in January 1939

Notes On The Fascist Doctrine of Race by Pasquale Pennisi, published in Gerarchia in July 1942

The Concept of Race In Fascism by Arturo Sabatini, extracted from the monthly magazine Razza e civiltà, Anno I, No. 2, 1940

The Jewish Problem In Italy by Roberto Pavese, published in Gerarchia in June 1942

Anti-Semitism by Salvatore De Carlo, published in the encyclopedia De Carlo in 1942.

Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini