Introduction

During the 20th century, conservative factions typically viewed the Soviet Union and its associated states, movements, and liberation fronts with suspicion and animosity. Right-leaning groups often sided with the Soviets' enemies, which ranged from reactionary elements and White Russian émigrés to German Nazis and the United States during the Cold War. The right's aversion to the Soviet Union stemmed from various factors, including its official stance on atheism and early efforts to suppress Christianity. Nevertheless, a shift was noted in the mid-1930s as the Soviet Union appeared to transition towards a more socially conservative and nationalistic stance, moving away from its earlier progressive and internationalist agenda.

The Soviet Union was a consistent supporter of nationalist movements in the "third world," backing their fights for independence, especially against colonial powers like Britain, France, and the United States. Some Western right-wing figures, finding common ground in their adversaries, started to support pro-Soviet movements, revolutions, and regimes. They came to view the Soviet Union, once an enemy, as a possible ally in upholding traditions, cultural identity, and national sovereignty. As the Western world became more liberal and globalist, moving away from traditionalist values, these 20th-century conservatives considered the Soviet Union as a possible guardian of these ideals. This text seeks to explore the historical concept known as National Bolshevism, providing a neutral examination without casting ethical judgments on those involved.

“The world revolution, however, will not be that which Marx envisaged; it will rather be that which Nietzsche foresaw.”

— Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, Das Dritte Reich

The German National Bolsheviks of The German Conservative Revolution and Nazi-Bolshevism

In the aftermath of World War I, Germany experienced defeat and subsequent hardships, including territorial cessions, economic setbacks, and pervasive foreign influence from powers like Britain, America, France, and various international corporations. These conditions prompted many German nationalists and conservatives to perceive their country as a victim of external imperialistic forces. Seeking to counter this perceived imperialism and capitalism, they looked for solidarity with other colonized peoples and the Soviet Union. These sentiments were particularly strong among those associated with the German Conservative Revolution, especially its national-revolutionary wing. Prominent figures within this movement included Ernst Niekisch, Ernst Jünger, Ernst von Salomon, Paul Eltzbacher, Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, Heinrich Laufenberg, Fritz Wolffheim, and others, with many identifying as National Bolsheviks or holding similar views.

This German movement began in 1917, predating the similar Russian movement by two years. In contrast to the Russian National Bolsheviks and Eurasianists, who were mainly from the right, this German group had significant representation from the left, including members from the Social Democratic party (SPD), the Independent Social Democratic party of Germany (USPD), and the Communist party of Germany (KPD). Key figures like Ernst Niekisch, Heinrich Laufenberg, and Fritz Wolffheim were involved in socialist and communist revolutions in 1918, taking control in cities like Hamburg and Bavaria. Laufenberg and Wolffheim, in particular, started to develop their blend of nationalist and socialist ideologies among workers and soldiers in Hamburg, aspiring to a revolution that would unify Germany and free it from the influence of Anglo-American capitalism. They proposed an economy based on decentralized workers' councils.

“On the basis of which criteria will the proletarian dictatorship in Germany proceed with the overthrow of the bourgeoisie? In light of Germany’s high industrial level, the central emphasis lies with the masses of workers in the giant factories, masses who are united in a federalist manner by the capitalist production process itself and who will in the main provide the human basis for the future economy as well as for public reconstruction. For the communist state, which represents nothing other than the organization of the entire Volk by the working-class, these huge concerns are therefore the first cells of its existence, from which the organization of economy and state emanate. They have the preliminary task of bringing the proletarian class organization to life within their enterprises, across the dividing lines of the parties, and of developing out of it the initial stages of the council system via the Works Councils and the Local Councils. Insofar as those working masses who are not united in the large enterprises are concerned, organization will be carried out on the basis of residential districts in order to achieve the establishment of the Local Councils, whereby membership in the proletarian class organization constitutes the prerequisite for the right to vote, with this membership being conditional entirely upon the performance of productive or socially-beneficial labor. The forcible exclusion of all parties and other associations from the electoral process, which constitutes the basis of the council constitution, is the first organizational task of the proletarian dictatorship.”

— Heinrich Laufenberg and Fritz Wolffheim, Revolutionary People’s War or Counter-Revolutionary Civil War? First Communist Address to The German Proletariat

Despite their innovative approach, Laufenberg, Wolffheim, and their faction within the KPD in Hamburg faced resistance from many nationalists who were wary of their communist leanings, and in some cases, their movement was discredited due to personal backgrounds, as seen when a völkisch leader objected to Wolffheim's Jewish heritage. Ultimately, they were ousted from their council positions by more moderate Social Democrats. Subsequently, Lenin, similar to his stance on the Russian National Bolsheviks, criticized them in "Left-Wing" Communism: An Infantile Disorder. As a result, Karl Radek expelled them from the Communist party due to their decentralized council concept and nationalist ideals. Ironically, a few years later, Radek adopted many of their nationalist positions to appeal to nationalist workers and certain left-wing elements of the National Socialist party (NSDAP).

Amidst the convergence of individuals with pro-Soviet leanings from diverse ideological backgrounds, the emergence of German National Bolshevism showcased an intriguing fusion. Paul Eltsbacher, a notable figure with right-wing origins, played a significant role in this movement. As an economic professor of German Jewish descent, Eltsbacher perceived the Treaty of Versailles as a severe blow to German sovereignty. Consequently, he advocated for an alliance with the Soviets against Western powers, reinstating the Kaiser, and the nationalization of the economy as the means to regain sovereignty. Importantly, Eltsbacher distanced himself from advocating a dictatorship of the proletariat and aimed to avoid the excessive violence witnessed during the Russian Revolution.

On April 2nd, 1919, Eltsbacher articulated his thoughts in an article published in the German National party Newspaper, proclaiming, "There is only one way to end this affair. That way is Bolshevism." However, similar to the fate of Laufenberg and Wolffhiem, Eltsbacher faced expulsion from his party and encountered blacklisting from numerous conservative groups. In contrast to the Hamburg Communists and the Conservative Revolutionaries, this marked the conclusion of Eltsbacher's narrative. In response to Eltsbacher's ideas, Hans von Seeckt presented proposals aimed at fostering closer relations between Germany and the Soviet Union. This effort triggered a campaign of pro-Soviet propaganda orchestrated by influential figures, such as Alexander von Falkenhausen and Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Otto Gotsche, a celebrated historian and an authority on Eastern affairs, also lent his support to the idea of enhanced cooperation with Soviet Russia. He emphasized the necessity of inviting Soviet troops to Germany as a strategic step to dismantle the Versailles system. During the Polish-Soviet War, Seeckt actively maintained communication with Leon Trotsky, the Chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Soviet Republic. Their discussions revolved around the prospect of dismantling the Versailles system through a collaborative effort with the Red Army. However, despite initial diplomatic progress, the envisioned alliance between Germany and Russia failed to materialize as anticipated.

A significant milestone occurred with the signing of the Rappel Treaty in April 1922, signifying the resumption of full diplomatic relations between Germany and Russia. This treaty served as a reaffirmation of the longstanding Russophile Prussian-German tradition. Nonetheless, it encountered opposition and criticism, notably from sources like the Völkischer Beobachter, which denounced it as the "Rappel crime of Rathenau." The newspaper depicted the treaty as a personal union between Jewish financial oligarchy and international Jewish Bolshevism. After 1923, military contacts between Germany and Russia were established discreetly. General Werner von Blomberg, a prominent military leader, expressed his enthusiasm for maintaining close military relations with Kliment Voroshilov, a notable figure within the Soviet military. Despite these interactions, the broader vision of a robust alliance between the Reichswehr and the Red Army failed to materialize.

Following their expulsion from the KDP, Laufenberg and Wolffhiem played a role in the formation of the German Communist Workers party (KAPD) in April 1920, which became a significant challenge to the KDP. However, they were once again expelled, this time due to pressure from both the KDP and Vladimir Lenin. This led Laufenberg to denounce Lenin and his New Economic Policy (NEP) as a "betrayal" of the Bolshevik Revolution. Subsequently, Laufenberg and Wolffhiem had only a few small revolutionary circles associated with them, most notably the Bund der Kommunisten. They had a limited following of a few hundred loyal supporters, and Laufenberg eventually retired from politics, passing away in 1932. Wolffhiem remained active in politics and regained prominence among the Conservative and National Revolutionaries, as well as the subsequent generation of National Bolsheviks, who became more influential than the original National Bolsheviks themselves.

An additional faction of note is Werwolf (also known as Armed Wolf), a collective of German veterans from World War I, spearheaded by Fritz Kloppe. Established in 1923, Werwolf evolved from the Steel Helmet group, serving as its youth division with a focus on military preparedness for future members. Its ranks were filled predominantly with ex-Freikorps fighters, former military officers, and reserves. They distanced themselves from the Steel Helmets due to a perceived preoccupation of the latter with upholding middle-class interests. Werwolf was characterized by intense nationalism and a declared readiness to lay down their lives for Germany without hesitation.

Werwolf propagated an economic concept termed "Possedism," coined by Kloppe in 1931. This concept was aimed at transforming property relationships, contesting that capitalism allowed for a concentration of property that bred rampant individualism and a neglect of national interests. Kloppe's vision involved the state nationalizing land and assets, then distributing these for individual "possession" as broadly as possible. The ambition was to ensure that every German could have an inheritable share in the nation's land or industry, thus cultivating a collective sense of ownership and dedication to the national welfare.

“In other words, we want not a struggle of an occupational strata, one that is exploited or is under threat by High Finance, against another, but instead a joint uprising by all peasants, workers, and soldiers – the last of which being a reference to all those people from other professional classes who regard the struggle against the enemies of the German Volk as their most important purpose in life.

The Volk in its totality, the Nation, is to have proprietary right over all possession. As proprietor, the Nation consequently can exercise the right of intervention at any time and, indeed, against anyone.”

— Fritz Kloppe's speech on "Possedism" at the Bonn am Rhein Whitsunday Celebrations, 23rd – 25th May 1931

Werwolf's messaging vehemently opposed capitalism and plutocratic systems. Initially self-identifying as National-Revolutionary, their ideology harbored pronounced elements of revolutionary socialism, making the term National Bolshevik a more fitting descriptor. They also supported the idea of strengthening ties between Germany and the Soviet Union. At its peak between 1924 and 1929, Werwolf's membership swelled to an impressive 30,000 to 40,000 individuals. However, as Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party gained prominence, Werwolf's numbers dwindled to around 10,000, and eventually, the organization was fully integrated into the NSDAP.

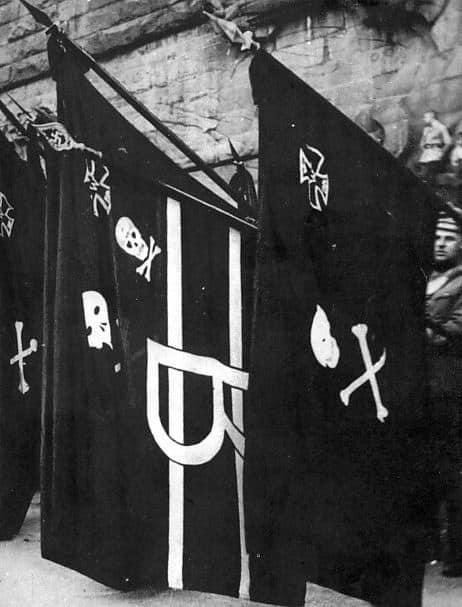

Werwolf/Possedism propaganda

Various rare photos of Werwolf

After expelling the National Bolsheviks, Karl Radek, the leader of the German Communist Party, adopted many of their positions in 1923 to appeal to nationalist workers and middle-class individuals, even attempting to attract members of the NSDAP. Radek held discussions with German nationalist general Eugen Freiher von Reibnitz and even shared a stage with German conservative thinker Arthur Moller van Den Bruck. In the same year, Moller published a book called Third Empire, which advocated for a German socialism based on figures like Otto von Bismarck and Friedrich List, and criticized English liberalism while praising Russian Bolshevism as an authentic form of socialism for Russia. Moller's book had a significant influence on nationalist and pro-Soviet right-wing figures, including Otto Strasser and Karl Otto Paetel.

Radek allowed Moller to publish articles in the communist journal, along with the anti-Semitic völkisch writer Ernst Reventow. The question arises as to why communists and nationalists started collaborating at this time instead of earlier. The answer lies in a declining capitalist economy, the French-Belgian occupation of the Ruhr, and a shared growing hatred of capitalism, liberalism, and parliamentarism. There was also a growing sympathy for socialist and nationalist causes on both sides, which facilitated this collaboration. Radek delivered nationalistic speeches and glorified Leo Schageter, a member of the Freikorps and NSDAP who was executed by the French military for sabotage in the Ruhr. Ernst Reventow and Arthur Moller van Den Bruck endorsed Russia as a "natural ally" to the proletarian nation of Germany. Nationalists and communists even protested together against the occupation of the Ruhr.

During this time, many German political parties and factions had nationalist or strong anti-capitalist sections within their organizations. These groups often competed with each other to prove who was the true "nationalist" or "socialist." However, there were still clear differences between these groups. Those with conservative or nationalist backgrounds, like Arthur Moller Van Den Bruck and the NSDAP, favored class collaboration over class struggle, unlike the KPD. It is worth noting that many of these socialist, nationalist, or conservative socialist individuals were primarily influenced by Marxism, although they were also influenced by other writers such as Friedrich List or Rudolf Jung (in the case of the NSDAP). However, some NSDAP members, like Adolf Hitler, and Conservative Revolutionaries, like Oswald Spengler, preached a nationalistic socialism but were anti-Soviet. There were often street fights and verbal attacks exchanged between these factions, especially by Adolf Hitler, who accused the KPD of being controlled by Jews. Additionally, the KPD did not share the racial or anti-Semitic views of the NSDAP or völkisch factions, like Ernst Reventow.

Within the conservative revolution and other nationalist circles, there were factions that sought an alliance with the Soviets and believed in class struggle as a means of national liberation. However, they did not believe in progress or egalitarianism and were highly critical of both the NSDAP and KDP. National Revolutionaries like Ernst Niekisch, Karl Otto Paetel, Ernst Jünger, and Ernst von Salomon played significant roles in influencing radical nationalist and socialist scenes through their participation in journals, political parties, and movements.

Ernst Niekisch, in particular, was influential in promoting pro-Soviet positions. He initially belonged to the SPD and played a role in the formation of the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic in 1919, which led to his imprisonment. In the 1920s, Niekisch expressed more nationalistic views within the SPD, resulting in his expulsion in 1926. He then founded the National Bolshevik magazine, Widerstand, which became highly popular. Renowned German novelist Ernst Jünger and his brother Friedrich even contributed to the magazine. Niekisch also joined the Old Social Democrat party and steered it towards a more nationalistic direction. The party achieved electoral success, winning four seats in the Saxony parliament and receiving over 65,000 votes at its peak.

Widerstand magazine distinguished itself from major parties like the NSDAP and KDP. It criticized the NSDAP's anti-Soviet policy as self-destructive and argued that Adolf Hitler's National Socialism was not true socialism. The magazine also strongly opposed imperialism and sought alliances with colonized peoples worldwide. It displayed open hostility towards Christianity, considering it a "foreign" Latin religion and accusing Hitler of being under the control of the Catholic Church. The magazine exhibited sympathies towards German Paganism. While these positions may seem similar to those of the KDP, there were distinct differences. Niekisch and the magazine rejected the idea of historical progress, a fundamental aspect of Marxism, and they also did not believe in the attainment of an egalitarian and classless society. They viewed these concepts as grand myths that could motivate the masses but were unattainable.

Niekisch also criticized Marx for agreeing with the capitalist process of eroding nations, ethnic identities, and traditions, which he vehemently opposed.

“Marxism is more than a red flag, in the proper and figurative sense, which then permits it to carry the masses, uneducated and undemanding, and put them in states of blind excitation.”

“Thus, they waited with impatience for this paradise that would become their hell. However, this self destructive folly was provoked with the aid of the thought of the German philosopher, Hegel. The dialectical dynamic was the magic formula of the great spirit. Under its supernatural light, it accomplishes the transubstantiation of the thankless way of technical progress along the road of grace towards salvation. It must push to the extreme mechanization, rationalization, monopolism, and proletarianization. That is the sole means of arriving at the “expropriation of the expropriators.” Within the capitalist society, approaching its apogee, the fruit of a beautiful socialism ripens. The persuasive force of the dialectical dynamic was due to the fact that the idea seems to be more than an amusing thought game and they must recognize it as the faithful image of a future reality. The walls and the gables of the slaughterhouse shine in the distance, in the mists colored with blood, such an aurora. Their silhouette resembles a fairy tale castle. Irresistibly, they wait for their victims – who hasten to arrive at the castle.”

“Marxism creates illusions and provokes enthusiasm in place of warnings.“

“By the force of things, humanity lets itself be carried by this current. Already the wind carries the spray of distant whirlpools. The shade of dangerous reefs draws itself on the horizon. Marxism greets them as isles of happiness.“

“Marxism attracts the view in the direction of the onward march, puts him in a fury. Marxist doctrine is naive. It glorifies the progress that will destroy its followers.”

— Ernst Niekisch, Technology: The Devourer of Men

Niekisch held the belief that through the class struggle, the nation could be revitalized by toppling the outdated and feeble ruling class. However, he deemed the KDP ill-equipped to fulfill this crucial mission. In 1929, the global economic depression hit, causing widespread unemployment and reviving interest in radical politics. This was a significant year for national revolutionaries and Germany as a whole. It was during this time that Niekisch visited the Soviet Union in 1930. Ernst Jünger, along with political theorist Carl Schmitt, also frequented the Russian Embassy. Niekisch's trip to the Soviet Union coincided with the rise of radical politics due to the economic crisis, providing opportunities for various ideological groups to gain power.

This brings us to Karl Otto Paetel, the final German National Bolshevik thinker. Unlike many others mentioned, Paetel was not actively involved in political or revolutionary activities for years. He was a college student at Friedrich Wilhelm University in 1928. However, Paetel had always harbored nationalist sympathies and found himself protesting with other students and youths outside the French Embassy. He was arrested alongside many others and found himself torn between the Communist youth and the Nazi students. It was during this time that Paetel's ideas as a National Bolshevik began to take shape. Paetel was expelled from the university and started writing for various publications. He also joined the Deutsche Freischar, a nationalistic youth movement. Under the influence of Ernst Niekisch, Ernst Jünger, and other national revolutionaries, Paetel's writings became more radically socialist, calling for nationalization and land redistribution. This eventually led to his departure from the Deutsche Freischar. Paetel then joined the Young Front Working Circle, a group dedicated to collaboration between right and left radicals.

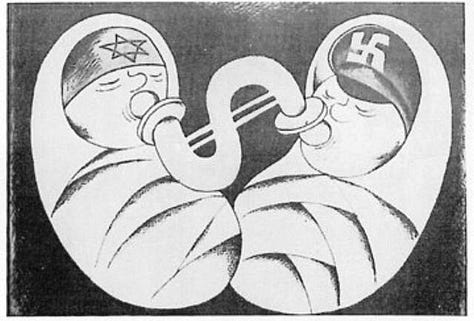

The Soviet magazine Pepper showing the friendship between the Soviet and German proletariat

In May 1930, the Young Front Working Circle was reorganized into the Group of Social Revolutionary Front (GSRN), with Paetel as its leader. Fritz Wolffhiem also joined the group. The GSRN initially tried to appeal to the Nazis and push them in a more socialist and pro-Soviet direction, even attempting to tap into their anti-Semitism. They achieved some success on a grassroots level among members who were dissatisfied with Hitler's moderate stance on economic issues. However, they ultimately turned to the KDP, which had just released another nationalist and anti-imperialist program. The GSRN sought to rally nationalists to the KDP and participated in protests alongside them, adopting their anti-Fascist position and engaging in clashes with the NSDAP. However, like the NSDAP, the GSRN became disillusioned with the KDP, believing that the party was not genuinely nationalist.

When discussing the subject matter centered on Germany, it is important to acknowledge France as well. In this regard, an interesting organization called Cercle Proudhon emerged in France during the early 1900s. The organization took its name from Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, a renowned anarchist philosopher from the 19th century. Cercle Proudhon sought to combine elements of anarchist syndicalism and nationalism, advocating for a decentralized society with a strong national identity. Zeev Sternhell's analysis of the organization provides valuable insights into the ideological and historical aspects of this development. Notably, the influence of Cercle Proudhon extended to the German Conservative Revolution. The German National Bolsheviks, led by Niekisch, embraced the symbol of Cercle Proudhon as a representation of their envisioned synthesis between nationalism and socialism.

Constantin von Hoffmeister, sheds light on the significance behind their use of this symbol.

“Amidst the swirling mists of history and the murmurings of destiny, there emerges an icon — noble and arcane. An eagle, grand and untamed, stretches its mighty wings across the breadth of the Eurasian expanse. In its talons, it holds fast to a hammer and sword — emblems of the worker’s labor and the warrior’s valor. A banner of profound symbology unfurls in the imagination, wrought in the loom of National Bolshevism.”

— Constantin von Hoffmeister, National Bolshevism: The Eurasian Dream

The Cercle Proudhon and National Bolshevik eagle

Ernst Niekisch's Widerstand journal

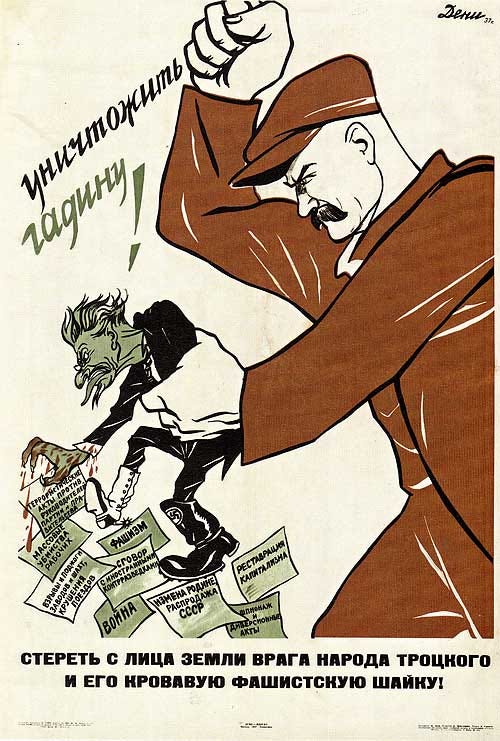

A propaganda poster used to advertise a revised, National Bolshevik programme for the NSDAP, written by Karl Otto Paetel and his supporters in late 1929

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, two significant movements emerged alongside the National Revolutionaries: the Black Front and the Agrarian Movement. Led by Otto Strasser, the Black Front split from the NSDAP in 1930 due to disagreements with Hitler over his response to recent labor strikes, his authoritarian tendencies, and what they viewed as his "fascist" approach. The well-documented tension between Strasser and Hitler stemmed from their conflicting views on the NSDAP's ideology. While the Black Front aligned itself with National Socialism, it adopted a more moderate stance, openly rejecting anti-Semitism and collaborating with Jewish individuals like Kurt Hiller and Helmut Hirsch.

Strasser advocated for a strategic alliance with the communists to overthrow the Weimar Republic and abolish the Treaty of Versailles. He considered the British Empire a greater threat to Germany than the Soviet Union and supported India's fight for independence from British colonial rule. Influenced by prominent Conservative Revolutionaries such as Oswald Spengler, Werner Sombart, and Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, Strasser incorporated their symbolism and slogans into his own ideology. In fact, he criticized fascism for being no different from Soviet communism.

“Fascists and communists are the first to exalt the state, the first to repress economic and personal independence, the first to exalt the excesses of power, the success of organization, decree, planning, and - last but not least - the police.”

— Otto Strasser, Germany Tomorrow

The Black Front quickly captured the attention of Karl Otto Paetel and fellow National Revolutionaries. Nonetheless, Paetel's interest waned as he took issue with Strasser's aversion to Marxism, materialism, and internationalism. Strasser's Christian faith shaped his political views, which leaned towards agrarianism and economic Guild Socialism. In contrast, Paetel, a Pagan, championed industrial growth, state centralization, materialist and Marxist economics, and a form of "patriotic" internationalism. Despite their ideological conflicts, the Black Front was instrumental during the 1930s in challenging the NSDAP's dominance. They instigated an SA mutiny, engaged in violent confrontations with Nazi supporters, and forged partnerships with various anti-Hitler factions.

While there were disagreements and divisions among the National Revolutionaries and the Black Front, they all supported the Rural Movement. The Rural Movement consisted of small farmers who protested against the government's economic policies and the Treaty of Versailles. They refused to pay taxes, engaged in protests, and sometimes even resorted to rioting. The National Revolutionaries and the Black Front saw potential in this movement and rallied behind it. Figures like Ernst von Salomon and his brother Bruno participated in the movement, running a supportive magazine called Landvolk and carrying out bombings against government buildings (though these actions were unpopular within the wider movement). Ernst Niekisch also expressed sympathies for the movement, giving speeches and writing positively about it.

At the time, the Nazis did not enjoy popular support among the farmers, which presented an opportunity for the National Revolutionaries and the wider Conservative Revolution. However, they failed to capitalize on this advantage. Prominent leaders like Claus Hiem and Ernst von Salomon were arrested for their involvement in bombing campaigns, causing the movement to lose mass support and giving the NSDAP more influence over the rural population. Additionally, the Conservative Revolutionaries were divided on whom to support in the 1930 elections. Niekisch backed Claus Hiem, hoping that his victory would secure Hiem's release from prison. Others, like Ernst von Salomon, joined the Communist party, while Otto Strasser and Karl Otto Paetel abstained from electoral politics due to their anti-parliamentarian stance. None of these attempts succeeded, and the Rural Movement continued to decline. However, Niekisch's influence persisted within the movement until 1933. This marked the last opportunity for the German Conservative Revolution to become a popular movement and overthrow the Weimar government, but it ultimately failed.

In a crucial historical juncture in 1935, with tensions simmering between Germany and Italy after the assassination of the Austrian prime minister and Germany's territorial aspirations, an important conversation transpired between Benito Mussolini and Ernst Niekisch. Niekisch, a German National Bolshevik and vocal critic of Hitler, reached out to Mussolini in search of allies to combat the Nazi regime. During their private meeting, Mussolini expressed his own reservations about Hitler and shared his thoughts with Niekisch on Karl Marx:

“Isn't it true that one must go through the school of Marxism to acquire a true understanding of political realities? Those who have not passed through the school of historical materialism will remain mere ideologists."

— Benito Mussolini quoted in Niekisch and Mussolini by Ernst Niekisch

Despite their persistent efforts to resist Hitler and the NSDAP, including the Black Front, National Revolutionaries, and the broader Conservative Revolutionary movement, they ultimately failed to overthrow the Nazis. Despite their attempts to undermine Hitler, he skillfully thwarted their actions and disrupted anti-Nazi gatherings. In a notable incident, the Nazis ambushed Otto Strasser but were unsuccessful in their attempt to eliminate him. Ultimately, Mussolini aligned himself with Nazism, shifting the political landscape in favor of Hitler. In 1933, just before Hitler's election, Karl Otto Paetel published the final significant work of German National Bolshevism: The National Bolshevik Manifesto of 1933, which outlined his views.

“Such a 'National Bolshevist' position is today no longer so surprising as it was years ago. Ever more circles of people, especially of the younger generation, are today of anti-capitalist disposition, are through their mindset 'National Bolsheviks' even if they do not use the term."

— Karl Otto Paetel, The National Bolshevik Manifesto

Hans Zehrer, another significant yet underrecognized figure within the Conservative Revolutionary movement, played a crucial role during the 1928-1933 period, overshadowing contemporaries like Niekisch and Paetel. A veteran of the Great War and participant in the 1920 Kapp Putsch, Zehrer transitioned into political journalism, notably transforming the national journal Die Tat into Germany's leading political publication by advocating a unique blend of anti-capitalist socialism and nationalism. His vision rejected the conventional political spectrum, aiming instead for a “Third Front” that united all militant forces across the spectrum under a vision of national unity and elitism, while opposing the NSDAP. Zehrer's zenith occurred under Kurt von Schleicher's government, with Die Tat serving as an unofficial ideological platform. His writings, exemplified by a 1932 Die Tat article Right or Left?, argued for transcending the left-right divide to achieve a unified national community, suggesting common goals and ideologies between seemingly disparate political factions, and envisioning a synthesis that could address future challenges by forming a new national unity beyond traditional political divides.

“The way of the future involves bringing together this man of the Right with the man of the Left, and vice versa, in order to create out of both a new Volksgemeinschaft under the mythos of a new nation.”

— Hans Zehrer, Right or Left?

After Hitler seized power, the Conservative Revolutionary movement faced a crackdown, leading to the proscription of groups like the Black Front and the suppression of Paetel's manifesto. In defiance, Paetel and his allies established initial anti-Nazi resistance networks. The 1934 Night of the Long Knives purged internal Nazi Party dissent, killing Conservative Revolution adherents like Edgar Jung, and subsequently, all competing political parties were outlawed. Otto Strasser and Karl Otto Paetel escaped Germany, while those who stayed behind organized underground resistance. Strasser set up a broadcast operation in Czechoslovakia to air anti-Hitler propaganda into Germany and tried to orchestrate an attack on NSDAP's Nuremberg base, which failed. After his radio station was thwarted and the Black Front collapsed in 1937, Strasser emigrated to Canada, his subsequent resistance efforts proving ineffective. Paetel's post-exile life is largely undocumented, except for his relocation to the U.S. Karl Radek of the KPD fled to the USSR post-1923 Hamburg uprising, later perishing under Stalin in 1939.

Otto and Paetel found refuge abroad, unlike many associates who suffered in concentration camps, such as Fritz Wolffhiem, who died in Ravensbrück, and Beppo Romer, who was executed following torture for his role in a plot to kill Hitler. Ernst Niekisch, although surviving the camps, was left blind. Prior to his capture, Niekisch sought an alliance with Mussolini, despite contentious German-Italian relations over Austria, where German-aligned Austrian Nazis clashed with Italy's ally, the Austrian fascist government. Niekisch, despite agreeing with Mussolini on the perils of Hitler's policies towards the Soviet Union, was arrested in 1937, with his publication Widerstand being shut down earlier in 1934. Only German Ambassador Ulrich von Hassel acted on their shared concerns, participating in the failed July 20th Plot against Hitler.

“Hitler was elevated to the cardinal of civil society at the right hour; the economic leaders had been nimble enough and had not saved. He has since been practicing the rebel method to save the legitimate civil cause. This is his social Jesuitism, which is not hidden from anyone who still has his sense of smell. His "National" Socialism is the timely protective coloring of shaken capitalism; capitalism uses it to find entrance within the ranks of its natural enemies to disarm them.”

— Ernst Niekisch, Hitler: Germany’s Evil Fate

Beyond Niekisch and Wolffhiem who were apprehended early, figures like Ernst Jünger and his brother Friedrich managed to avoid arrest despite house raids by the German police. Ernst Jünger was involved in the 1944 July 20th plot to kill Hitler and suggested a peace proposal to preserve German sovereignty. He also helped Jews, like Sophie Ravoux, disguise their identities and alerted the French Resistance of imminent Jewish deportations while stationed in France during the war.

Ernst von Salomon, another figure in the Conservative Revolutionary movement, concealed his Jewish wife from Nazi detection and maintained links with the Red Orchestra resistance network, which leaked German military intelligence to the Soviets. Despite its communist leanings, the Red Orchestra had connections with nationalist and conservative resisters, including Harro Boysen, a former member of Otto Strasser’s Black Front, who was executed by the Nazis in 1942. Marxist economist Arvid Harnack, another Red Orchestra leader who collaborated with Ernst Niekisch and Ernst Jünger in the ARPLAN society, was also executed in 1942.

The July 20th conspiracy, including individuals like Ernst Jünger and Ernst Niekisch, and others such as Ulrich von Hassel, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, and Klaus von Stauffenberg and his brother Berthold, aimed to assassinate Hitler and initiate a coup. The plot failed, and the coup was the last significant Conservative Revolution and pro-Soviet right effort to dethrone Hitler. Less than a year later, Hitler took his life, and Germany capitulated, but this didn't signal triumph for Germany's pro-Soviet right as the nation split into East and West, with many facing ostracism by the pro-Western government. Some, like Ernst von Salomon and his wife, endured mistreatment in an American prison. Others, like Ernst Niekisch, became disenchanted with their past ideologies in East Germany. Karl Otto Paetel lectured on German National Bolshevism in the U.S., but his political endeavors ceased. Ernst Jünger, despite his contentious past, persisted as a prominent writer, shifting away from pro-Soviet views and being repudiated by East Germany. Salomon penned accounts of his political exploits, but his direct political engagement concluded.

During the Weimar Republic, Ernst Thälmann and the KPD pursued a strategy that often emphasized conflict with the SPD over a unified opposition to the emerging Nazi threat. This approach was influenced by the communist International's assessment, which foresaw an imminent collapse of capitalism. Thälmann and the KPD considered the SPD, due to their centrism, as perpetuators of the capitalist system and thus as significant obstacles to a communist revolution, labeling them as "social fascists." This perspective led to a strategy that sometimes prioritized undermining the SPD over directly confronting the rise of the Nazis.

“Let us not be ashamed to walk under the swastika banner and silence our own propaganda, if it will increase the number of Red flag sympathizers."

— Ernst Thälmann, An Stalin: Briefe aus dem Zuchthaus 1939 bis 1941

The complex relationship between the KPD and the SPD was further complicated by instances of cooperation between the KPD and the Nazis, most notably in 1933. In this period, the KPD and the SA took part in joint actions, such as an organized general strike in Berlin. This collaboration aimed to showcase the potential for a broad working-class movement against the Weimar government, sidelining the Social Democrats, whom the KPD viewed as betraying the working class. However, this strategy underestimated the Nazi agenda, unintentionally lending credibility to Hitler's regime and exacerbating divisions on the political left.

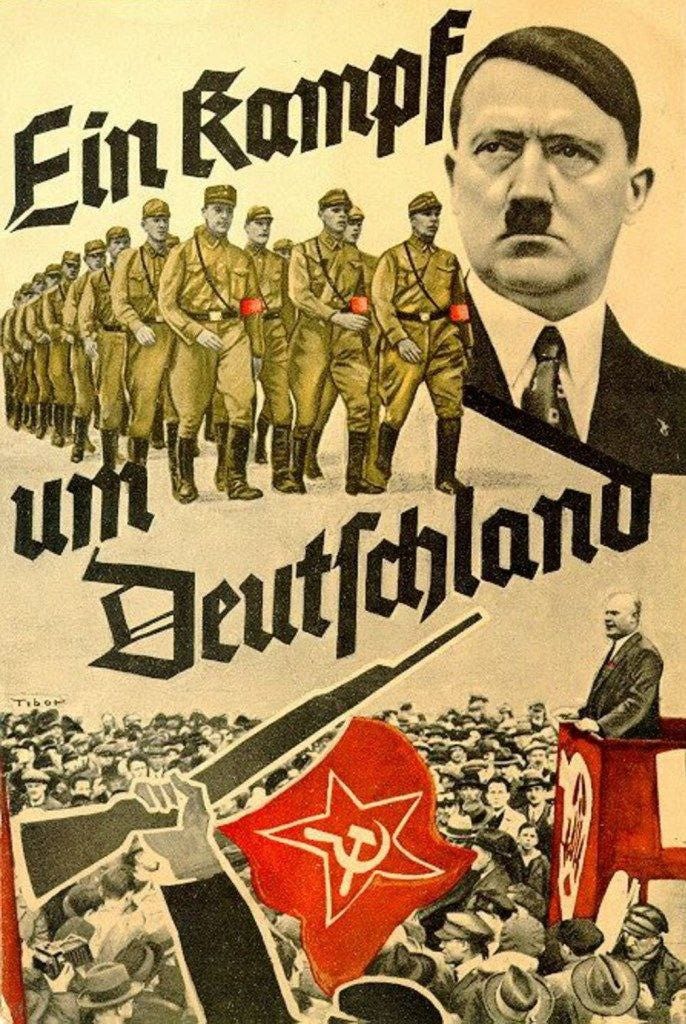

Designed by Dr. Goebbels for the collaborative effort between the NSDAP and the KPD

“Comrades! Workers! If you still wish to – as you have so far – remain tethered to the leash of Jewish world capital, if you wish to continue playing the role which you see in the adjacent picture, then this time also vote Social-Democratic or Communist!”

— German Socialist pamphlet, 1920s

The National Socialist Factory Cell Organization (NSBO), established in 1928 by worker groups primarily in Berlin's large factories, represented an intriguing manifestation of National Bolshevism within the Nazi party. Its creation aimed to provide a Nazi counterpart to existing unions, thereby extending Nazi influence among the working class. By January 1931, it had been officially designated as the German Reich Factory Cell Organization of the Nazi party. Despite this, the NSBO only achieved notable success in certain areas, supporting workers' strikes like the Berlin Transport Strike of 1932 in specific instances.

A faction within the NSBO embraced ideas similar to National Bolshevism, arguing that a "social revolution" was necessary to follow the anticipated "national revolution." This would be aimed at overthrowing the dominant elites. This group viewed the Soviet Union favorably within the context of German geopolitics and expressed a deep skepticism towards the "plutocratic West." This perspective found particular traction in places such as Nordhorn, a textile industry hub in Bentheim County. Here, in 1933, the NSBO managed to outperform the communists in worker council elections and even took up arms to challenge wage reductions at some factories. However, the landscape shifted drastically in May 1933 when the Nazi regime banned all non-Nazi trade unions, leading to the absorption of the NSBO into the German Labor Front. This marked the end of the NSBO as an independent entity, as it was integrated into Germany's sole permitted labor organization under the Nazi regime.

Adolf Hitler's ideology exhibited intersections with National Bolshevik concepts, significantly shaped by Karl Haushofer's influence during their joint incarceration in Landsberg in 1923. Haushofer's "Geopolitik" promoted a vision of a powerful Eurasian "great space" under German hegemony, echoing an interpretation of Eurasianism. Building upon Friedrich Ratzel's groundwork, Haushofer's geopolitical theories were rooted in a social Darwinist view of the state as an organic entity with an inherent drive for expansion. This expansionist drive was seen as a natural state impulse, analogous to biological organisms, suggesting that it was normal for larger states to assimilate smaller ones. Ratzel and Haushofer critically assessed and ultimately rejected 18th-century liberal principles, which posited sovereign nation-states with intrinsic rights, such as self-determination, even against stronger states. They regarded these liberal notions as misleading, serving as a facade for dominant states to exercise their power while feigning adherence to a moral code that they themselves did not observe. In contrast, Ratzel and Haushofer proposed a more forthright, amoral, and pragmatic approach to geopolitics.

In their development of the Lebensraum (Living Space) concept within geopolitical theory, Ratzel and Haushofer posited the state as an organically-driven entity seeking territorial expansion. These concepts were later co-opted and actualized by Hitler and the NSDAP. From an anti-liberal German stance, Haushofer also expanded on Halford Mackinder's Heartland Theory, asserting the strategic necessity for Germany and Russia to jointly secure the Heartland and Rimland of Eurasia against Anglo-American naval supremacy. Whether through annexation or alliance, the ultimate aim was to consolidate Eurasia into a significant counterforce against Anglo-American maritime power. These ideas mirrored those of National Bolsheviks, who likewise underscored the imperative of Eurasian unity, albeit favoring a Moscow-centric version of Eurasianism rather than Berlin-centric.

Carl Schmitt, a prominent legal theorist in the Third Reich, deepened the ideological connections within this context. Schmitt's legal theories justified and legitimized the expansion of states into "large spaces," sometimes at the detriment of smaller sovereignties. He challenged the concept of a globally uniform "rules-based order" as espoused by liberal theorists of the time. Schmitt argued that powerful nations create and enforce their own set of rules within their realms of influence, effectively controlling the political entities therein. These rules, he contended, are not universal truths but constructs of power relations, holding sway only while the dominant nation can uphold its order through its might. Schmitt's ideas resonate with Russian philosopher Alexander Dugin's Theory of a Multipolar World, which also rejects a single hegemonic power structure. Echoing Haushofer, Schmitt supported German territorial expansion eastward, emphasizing the strategic importance of consolidating the Rimland to resist Anglo-American naval dominance and protect the Eurasian Heartland.

“The concept of humanity is an especially useful ideological instrument of imperialist expansion, and in its ethical-humanitarian form it is a specific vehicle of economic imperialism. Here one is reminded of a somewhat modified expression of Proudhon’s: whoever invokes humanity wants to cheat. To confiscate the word humanity, to invoke and monopolize such a term probably has certain incalculable effects, such as denying the enemy the quality of being human and declaring him to be an outlaw of humanity; and a war can thereby be driven to the most extreme inhumanity.”

— Carl Schmitt, The Concept of The Political

Dr. Joseph Goebbels, the Propaganda Minister under Hitler, also shared these expansionist views, but he envisaged Germany achieving its geopolitical aspirations through diplomatic means and alliances, rather than solely through aggression. Goebbels found some agreement with the National Bolsheviks within Germany, appreciating their mutual aversion to Anglo-American capitalism and what they viewed as Jewish-controlled finance. As Stalin's regime in the Soviet Union matured, Haushofer too recognized its alignment with German interests, viewing it as a bulwark against the same international forces Germany opposed and a liberator from the constraints of global financial systems.

Adolf Hitler, although influenced by the likes of Haushofer and Schmitt, also crafted his own nuanced view of Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union. Hitler came to respect Stalin's governance, perceiving the Soviet Union as having evolved substantially since its early Bolshevik days. He lamented the misunderstandings surrounding the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Stalin, wishing for a genuine rapport with the Soviet leader. This sentiment was not unique to Hitler; it was shared by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and Italian leader Benito Mussolini. Even amidst the distrust of the time, the Third Reich's leadership held out hope that Stalin's Soviet Union might become a reliable ally. This aspiration was occasionally apparent and provoked concern among the British and French governments. In 1940, the Soviet Union supplied crucial oil to Nazi Germany, which led to British and French plans to bomb Soviet oil infrastructure to disrupt the support to Germany.

Adolf Hitler's series of letters to Joseph Stalin, from late 1940 through to the middle of 1941, weave a complex tale of strategic reassurances and diplomatic maneuverings ahead of Operation Barbarossa. Beginning with a New Year's message on December 31, 1940, Hitler aimed to mitigate Soviet concerns about German forces moving to Poland, justifying this as mere reorganization away from the prying eyes of British intelligence. He assured Stalin of the temporary nature of these movements, promising a retraction after defeating England, and argued that such actions bore no intention of aggression towards the USSR. Hitler also dismissed any speculation about a potential conflict with the Soviet Union as baseless, stressing the importance of keeping their communications confidential. Marshal Georgy Zhukov, recounting a briefing by Stalin in January 1941, revealed that Hitler's communication was actually in response to a previous, unrevealed inquiry by Stalin himself regarding the rationale behind the German military's positioning in Poland. This exchange is a pivotal piece of a larger narrative in which Hitler sought to convince Stalin of Germany's peaceful intentions towards the USSR amidst the realignment of its forces.

In yet another pivotal letter on May 14, 1941, Hitler doubled down on his assertion that a lasting peace in Europe was contingent upon England's defeat. Despite acknowledging disagreement within his own ranks about this strategic direction, he sought to reassure Stalin that the German military buildup near the Soviet frontier was not a precursor to conflict. Hitler voiced apprehension about possible unintended aggressive actions by German military personnel, asking for Stalin's patience should such situations arise. He wrapped up by thanking Stalin for his concurrence on a matter not specified and proposed a future rendezvous to deliberate the end of the conflict with England and the formation of a new socialist global order.

“For a final solution of what to do with this bankrupt English legacy, and also for the consolidation of the union of socialist countries and the establishment of new world order, I would like very much to meet personally with you. I have spoken about this with Messrs. Molotov and Dekanozov.”

— Adolf Hitler quoted in What Stalin Knew: The Enigma of Barbarossa by David E. Murphy

Amidst Hitler's assurances, Joseph Stalin navigated the waters of Soviet-German diplomacy with increased prudence. While harboring a complex mixture of respect and caution towards Hitler, Stalin was careful to avoid any actions that might lead to a military confrontation. He considered the possibility that Hitler's intentions towards the USSR might be genuine as an opportunity, yet he remained alert to the risk of a rapidly worsening situation. In 1940, a significant economic agreement was struck between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, whereby the USSR supplied raw materials to Germany in exchange for military equipment. This deal helped Germany bypass the economic sanctions imposed by Britain. Discussions about possibly integrating the Soviet Union into the Axis alliance were held but never materialized.

Research by Russian historian Andrei Fursov sheds light on the complexity of Hitler's distrust toward his military leadership, specifically his concern that they might instigate a conflict with the USSR to serve British interests. This apprehension was not without merit. However, a widespread anti-Soviet stance and escalating distrust of Stalin played a crucial role in shaping Hitler's strategic choices. He found himself increasingly leaning on the guidance of the German intelligence services, which pushed for a preemptive assault on the Soviet Union, even as Hitler harbored personal doubts about such a course of action.

Fursov's investigations reveal the role of Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, a key figure in the German intelligence apparatus, who, unbeknownst to many, had been clandestinely collaborating with British Intelligence since 1939. Canaris engaged in manipulation through the alteration of orders, the fabrication of directives, and the suppression of genuine ones. His consistent communication with British Intelligence allowed him to influence the narrative within intelligence reports negatively portraying the Soviet Union, thereby swaying Hitler towards initiating Operation Barbarossa. The full extent of Canaris's betrayals would only come to light in 1944, unveiling the depth of his involvement in shaping the course of events leading up to the conflict.

Lecture by Andrei Fursov on how Adolf Hitler allegedly got tricked into attacking the USSR

The conditions stipulated by the Soviet Union for joining the Axis were deemed excessively stringent by observers. The Soviets aimed to expand their control over several territories, notably Finland and Romania, among others. This ambition extended beyond mere territorial acquisition; it was designed to significantly increase Germany's dependency on the Soviet Union for essential raw materials and resources. Such a move revealed the Soviet leadership's view of the relationship with the Third Reich; they did not perceive Nazi Germany as an ally of equal stature in their mutual confrontation with the Anglo-American powers. Instead, the Soviet Union intended to use the alliance as a means to eventually dominate Germany, effectively reducing it to a vassal state within the Soviet sphere. Consequently, this strategy suggested that Germany would not stand as an equal partner in shaping the envisioned new world order alongside the Axis powers but would rather become a vehicle for expanding Soviet geopolitical and ideological reach.

"Let us look now at the second possibility – namely, that Germany becomes the victor. Some propose that this turn of events would present us with a serious danger. There is some truth in this notion. But it would be erroneous to believe that such a danger is as near and as great as they assume. If Germany achieves victory in the war, it will emerge from it in such a depleted state that to start a conflict with the USSR will take at least 10 years.

Germany’s main task would be then to keep watch on the defeated England and France to prevent their restoration. On the other hand, a victorious Germany would have at its disposal a large territory. Over the course of many years, Germany would be preoccupied with the exploitation of these territories and establishing in them the German order. Obviously, Germany would be too preoccupied to move against us.

There is still another factor that enhances our security. In the defeated France, the French Communist Party would be very strong. A Communist revolution would follow inevitably. We would exploit this in order to come to the aid of France and to win it over as an ally. Later these peoples who fell under the “protection” of a victorious Germany likewise would become our allies. We would have a large arena in which to develop the world revolution.

Comrades! It is in the interests of the USSR, the Land of the Toilers, that war breaks out between the Reich and the capitalist Anglo-French bloc. Everything must be done so that the war lasts as long as possible in order that both sides become exhausted. Namely for this reason we must agree to the pact proposed by Germany and use it so that once this war is declared, it will last for a maximum amount of time. We must step up our propaganda within the combatant countries so that they are prepared for that time when the war ends."

— Joseph Stalin, speech to the Members of the Politbureau, August 19, 1939

This element was pivotal in influencing Hitler's determination to launch an offensive against the Soviet Union. Despite objections from his Foreign Minister Ribbentrop, who not only voiced his dissent but also forewarned of Germany's potential defeat to a Soviet envoy, Hitler's conviction in the strategic necessity of the invasion remained unshaken. In David Irving's Hitler's War, it's documented that Hitler dismissed Ribbentrop's suggestion to eliminate Stalin during the conflict, hinting at a certain degree of personal respect for Stalin. Furthermore, the Soviet Union's persistent refusal to acknowledge the rationale behind Japanese aggression against British and American targets showcased its reluctance to compromise its strategic interests, even in diplomatic engagements with Japan. This insistence on prioritizing its own objectives was a stance that ultimately played a part in China's decision to sever diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union amidst the Sino-Soviet split in 1977.

Following the assassination attempt on July 20, 1944, Adolf Hitler identified Wilhelm Canaris as a participant in the plot. Hitler lambasted this group as a clique of ambitious, morally bankrupt, and intellectually deficient officers who sought to assassinate him and dismantle the German military leadership. The bombing orchestrated by Colonel Stauffenberg resulted in severe injuries to Hitler's associates and the death of one. In response, Hitler was adamant about eradicating what he perceived as a malignant conspiracy against him.

The German traitors

Although Wilhelm Canaris was not an active participant in the July 20, 1944, assassination attempt, his actions from 1939 to 1944 significantly undermined Germany's military campaign against Britain and its burgeoning diplomatic ties with the Soviet Union. Despite these internal setbacks, there was a period where the Third Reich and the Soviet Union appeared to be on the verge of fostering a partnership based on their mutual opposition to Western influences. However, the manipulative strategies that ultimately benefited the Anglo-American Atlanticist powers led to the rapid dissolution of any hopes for a united Eurasian front against the Atlanticist powers of the West. The launch of Operation Barbarossa on June 22, 1941, decisively shattered the possibility of any alliance between Germany and Russia. Yet, the echoes of these aspirations for collaboration would reemerge during the Cold War, as reflected in the viewpoints of figures like Otto Ernst Remer and Leon Degrelle.

Otto Ernst Remer on the necessity of an alliance between Germany and Russia against Britain and America

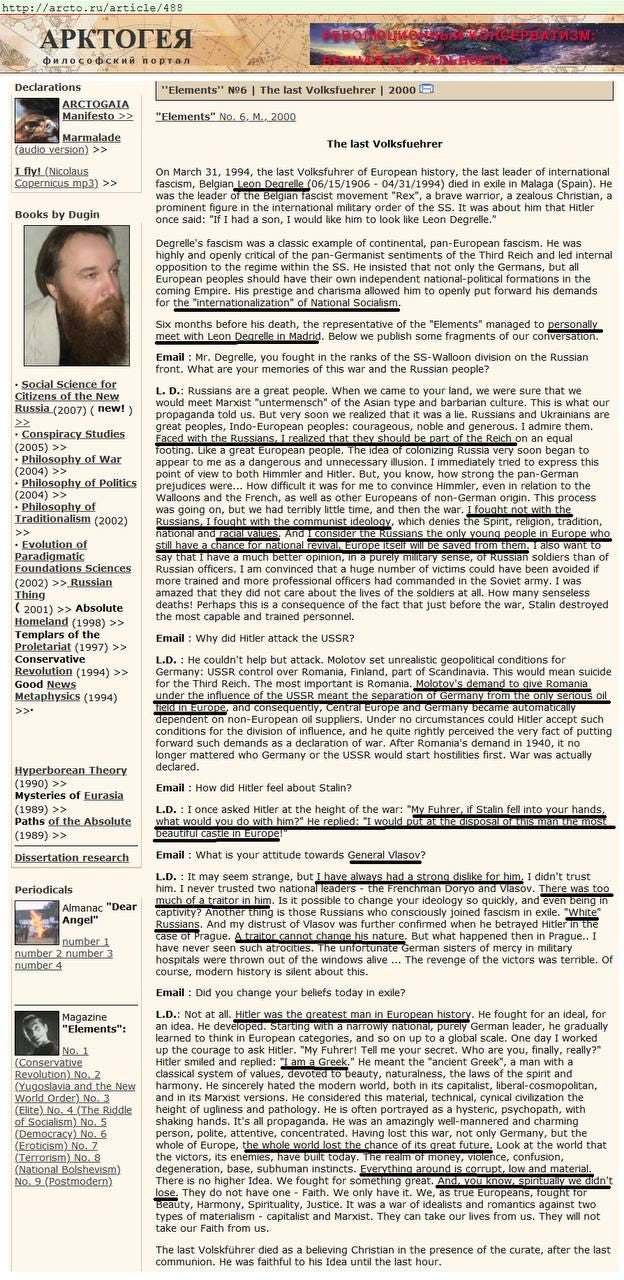

"In the West, the civilization of material gain is itself disgusting to young people, who cannot bring themselves to terms with the decline in the level of the digestive tract offered to them by the consumer society. Crime or drugs are the price of this situation. At a time when we are witnessing the awakening of Islam, while the American way of life leaves peoples dissatisfied, the youth of Europe are not offered any hope left to themselves and their spiritual suffering. Where is the solution? Well, I will surprise you at the risk of unleashing the wrath of new enemies on me: I expect a lot from the Russian people. He is still a healthy force, and he will not forever tolerate his regime of spoiled bureaucrats whose failure is complete in all areas."

— Leon Degrelle, Last Volksfuhrer interview by Elements magazine

In Rainer Zitelmann's book, Hitler's National Socialism, Zitelmann elucidates the contentious nature of Hitler's economic theories pertaining to the interplay between market forces and planned economies. Before ascending to power in 1933, Hitler strategically obscured his authentic economic ideology, underscoring the need for discretion about his economic strategies to enhance his prospects for gaining political influence. He thus oscillated between defending private property in some addresses and criticizing capitalism in others, always tailoring his rhetoric to resonate with his diverse audiences. Hitler's ultimate goal was to integrate the forces of competition and selection within a state-directed economy. He championed the idea that the needs of the collective should supersede individual ambitions, challenging the traditional priority given to personal interests.

After securing power, Hitler closely monitored Stalin's method of rule, leading to a transformation of his initial skepticism into a measure of admiration for the Soviet economic structure. He spoke favorably of the Soviet method of economic governance and showed a particular appreciation for Stalin's centralized planning. Evidence of this shift can be found in the records of Wilhelm Scheidt, which disclose Hitler's acknowledgment of a deep-seated ideological kinship between his own beliefs and those of Bolshevism, albeit considering his system to be a more refined and direct iteration. Consequently, it is reasonable to infer that such sentiments were shared among high-ranking Nazis, as evidenced by the likes of Joseph Goebbels, who is known to have remarked:

“Lenin was the greatest man, second only to Hitler... the difference between Communism and the Hitler faith is very slight..."

— Joseph Goebbels quoted in Hitlerite Riot In Berlin: Beer Glasses Fly When Speaker Compares Hitler and Lenin by The New York Times

“It would be better for us to go down with Bolshevism than live in eternal slavery under capitalism."

— Joseph Goebbels quoted in The Devil's Disciples: Hitler's Inner Circle by Anthony Read

Historian Dr. John Toland observed that Hitler's vision of an orchestrated economy bore striking resemblances to authentic socialism. Dr. George Watson concurred, suggesting that Hitler and his inner circle considered themselves socialists — a sentiment shared by some democratic socialists. Götz Aly, another historian, noted the past communist ties of several Nazi officials. Economic historian Peter Temin remarked on the Nazi state's strategy of consolidating industries into larger entities under greater state supervision. Historian Richard Overy documented the significant expansion of state-owned enterprises during the Nazi era. Henry Ashby Turner highlighted that capitalists and their organizations often financially supported the Nazis' adversaries or competitors. Economist Dr. Ludwig von Mises analyzed how the Nazi government regulated various economic facets, such as production, pricing, wages, and labor distribution, curbing profits and steering reinvestment. Historian Ian Kershaw pointed out that it was the state, not market forces, that shaped economic development in Nazi Germany. Jackson Spielvogel detailed the extensive economic controls imposed by the Nazi regime, including restrictions on foreign trade, prices, wages, and labor.

In synthesizing these views, historian Alan Milward argued that the economic direction of fascist states, including the Nazi regime, could be more precisely characterized as anti-capitalist rather than capitalist. Collectively, this scholarly interpretation suggests that Hitler and his regime embraced socialist and anti-capitalist economic principles, enacting measures that heightened state influence and curtailed the role of free enterprise. Hitler believed in the decline of capitalism and saw the future dominated by fascism and possibly Bolshevism. Even as the war drew to a close, Hitler lamented his inability to successfully eliminate the capitalist elements he believed had infiltrated his regime.

“We have liquidated the left-wing class fighters, but unfortunately we forgot in the meantime to also launch the decisive blow against the capitalist right. That is our great sin of omission."

— Adolf Hitler quoted in The Nazi War Against Capitalism by Nevin Gussack

During the era of the French Third Republic, a minor political group known as the French National-Collectivist party (PFNC), formerly the French National Communist party, emerged and later gained some prominence during France's occupation. Led by sports journalist Pierre Clémenti, the party initially adopted communist leanings but later incorporated facets of fascism, giving rise to "National Communism." The PFNC's economic views, while national communist in orientation, bore resemblance to those of council communism. They proposed a decentralized economy controlled by the working class, stressing worker sovereignty and communal ownership of production means. Their economic agenda aimed to create a society with workers at the helm of governance, fostering a more just allocation of resources.

The ideology of the PFNC extended beyond its economic stance to encompass facets similar to fascism, marked by racism and anti-Semitism. The party also championed pan-European nationalism and the concept of rattachism, promoting the idea of unifying French-speaking regions like Wallonia with France. Throughout the German occupation of France, the PFNC exhibited varying levels of cooperation with the Nazi occupiers. While the degree of collaboration differed among party members, there were clear examples of their willingness to work with the Nazi authorities. Clémenti himself had interactions with German representatives and showed an openness to working with the occupation forces. Additionally, some PFNC members were active in the Milice, a paramilitary group that assisted the Nazis in oppressive actions against the French resistance and Jewish communities. The collaboration between the PFNC and the Nazis involved not just political alignment but also sharing intelligence, collaborating on propaganda campaigns, and even recruiting French individuals to join the German military efforts on the Eastern Front.

The Soviet Union regarded the PFNC with suspicion and disfavor. During Stalin's leadership, the Soviet hierarchy insisted on a rigid form of international communism and retained tight control over the communist parties across different nations. The PFNC's blend of communism with fascist elements strayed from the Soviet model of communism and was seen as ideologically impure, diverging from Marxist-Leninist tenets. Moreover, the PFNC's collaboration with Nazi Germany was viewed as a stark violation of the commitment to combat fascism, and thus the Soviet Union rejected the PFNC as a legitimate communist entity. The PFNC, for its part, accused the Soviets of being pseudo-communists manipulated by Jewish Zionism.

In exploring the roots of Holocaust denial, a connection to France emerges, particularly among French Communists who actively resisted Nazi Germany during World War II. Despite their aversion to Soviet ideology, many of these individuals believed that the Holocaust narrative was a propaganda tool used by the Allies to manipulate Germany, conceal their own wartime actions, and financially strain the country.

One prominent figure in this movement was Paul Rassinier, an anti-Nazi Marxist associated with "La Vieille Taupe," a French Communist publishing house known for promoting Holocaust denial. Rassinier, a former prisoner of war captured by the Germans and sent to a concentration camp for his role as a partisan, emerged from his harrowing experience as a vocal Holocaust denier.

During the early 1960s, Rassinier corresponded with American revisionist historian Harry Elmer Barnes, who facilitated the translation of Rassinier's works. Barnes posthumously published a favorable review of Rassinier's book The Drama of The European Jews in the American Mercury under the title Zionist Fraud. In 1977, these translated works were collectively published by Noontide Press as Debunking The Genocide Myth, introducing Rassinier's writings to a wider English-speaking audience. In The Lie of Ulysses, Rassinier provides eyewitness testimony to assert that the Holocaust was a lie, which is why he is remembered as the father of Holocaust denial.

Additionally, it's vital to recognize National Bolshevism's influence within the Spanish Falange before General Franco's ascendancy. Ramiro Ledesma Ramos, a fervent supporter of this ideology, played a key role in its dissemination among the Falangists. His perspective is clearly reflected in this statement, as illustrated by the subsequent quote:

“Long live the new world of the 20th century! Long live Fascist Italy! Long live Soviet Russia! Long live Hitler's Germany! Long live Spain, we'll do it. Down with the bourgeois and parliamentary democracies!"

— Ramiro Ledesma Ramos quoted in Fascism In Spain 1923-1977 by Stanley G. Payne

The White Russian National Bolsheviks and Left-Eurasianism

In the early 20th century, the Russian Empire faced significant challenges, including economic poverty, political turmoil, and a decline in its global standing compared to nations such as Britain, Japan, Germany, and France. When World War I erupted in 1914, Russia promptly joined the conflict against the Central Powers. However, as the war prolonged, the Russian population experienced deteriorating conditions, leading to a liberal revolution in early March 1917. Later that year, in November, Vladimir Lenin and his Bolshevik party led a communist revolution. The Bolsheviks, as revolutionaries, aimed to catalyze a global proletarian uprising with the intent of dismantling established institutions such as nation-states, monarchies, and religious organizations. Their rigorous measures against the Tsarist regime, nobility, clergy, and others considered to be in opposition to their revolutionary goals sparked resistance among conservative and nationalist circles.

Yet, as the conflict unfolded into the 1920s and a Bolshevik triumph seemed more probable, certain elements within the White Army and the community of White émigrés began reconsidering their stance toward the Bolsheviks. They grew increasingly open to the idea that the Bolsheviks might pivot from their global revolutionary ideology and anti-religious stance to adopt a form of socialism more aligned with Russian nationalism, which could potentially restore Russia’s stature. Among these were the Smenovekhovtsy (Russian National Bolsheviks), under the leadership of the ex-Slavophile and White Army affiliate Nikolay Ustryalov, and the Eurasianists, a movement initiated by the Lithuanian nobleman Nikolai Trubetzkoy.

"The Civil War is lost definitely. For a long time Russia has been traveling on its own path, not our path... Either recognize this Russia, hated by you all, or stay without Russia, because a 'third Russia' by your recipes does not and will not exist… The Soviet regime saved Russia - the Soviet regime is justified, regardless of how weighty the arguments against it are... The mere fact of its enduring existence proves its popular character, and the historical belonging of its dictatorship and harshness."

— The Smenovekhovtsy magazine Smena Vekh, July 1921

Formed in 1921 and operating predominantly from outside Russia, the Smenovekhovtsy set up in China, while the Left Eurasians spread across Europe. Despite their physical separation, both groups reached similar assessments of the evolving Soviet Union and shared an ambition to reshape and integrate into the Soviet regime. They noticed the USSR was taking on more distinctly Russian or Eurasian traits and was veering towards nationalism, partly due to its international isolation. Both factions welcomed Lenin's New Economic Policy (NEP) and later, Stalin's “Socialism in One Country” doctrine, interpreting these policies as a departure from orthodox Marxism.

The Smenovekhovtsy and the Left Eurasians both placed a strong emphasis on geopolitics and foreign affairs in their ideologies. The Eurasianists, in particular, founded their political beliefs on geopolitical concepts, influenced by Nazi theorists like Karl Haushofer and Carl Schmitt, and other German Conservative Revolution intellectuals such as Ernst Niekisch and Arthur Moeller van den Bruck. They championed the idea that a nation's economic and cultural progress should align with its geographical confines and advocated for Eurasian unity against the liberal West. Both groups endorsed the idea of Soviet expansionism as a renewed form of Russian imperial ambition. Ustryalov criticized Western imperialism as racially motivated and destructive, while the Eurasianists proposed a unique racial view of Russia, recognizing Slavs, Mongols, and Turks as its principal races, and were strongly opposed to Western characterizations of Russian society as regressive.

To quote Alexander Dugin:

"The ethnic question was resolved by the Eurasianists in a very interesting manner. They have cast doubt on the previously accepted truths put forth by the Slavophiles regarding the negative impact of the Tartar invasion and the Mongol domination over Russia. The Eurasianists acknowledged the tellurocratic mission of the geopolitical expansion carried out by the Turkish and Mongolian peoples. Genghis Khan, in their eyes, was "the first of the Eurasianists," and the Turks were viewed as an ethnic group, or rather, a young and dynamic Eurasian race, full of creative and imperial potential. However, it was in conjunction with the Slavic genius (thus being Indo-European and Aryan) that the Turkish race succeeded in establishing the Eurasian equilibrium. The Eurasianists saw the Russians as a distinct Slavo-Turkish race endowed with two primary qualities: the expansive energy over vast territories inherent in the Turks ("horizontal") and the metaphysical and "vertical" energy of concentration specific to the Slavs. This racial synthesis, according to the Eurasianists, held the key to Russia's cultural history. They regarded the European race as the old race, feeble and possessing the geopolitical consciousness of the populations residing in the "rimlands," thus lacking the capacity for the extraordinary efforts required to organize the Empire, the grand autonomous space."

— Alexander Dugin, The Russian Conservative Revolution

Moreover this was also understood by Russian Fascists:

“The Russian nation is the spiritual unity of all Russian people on the basis of consciousness of a common historical destiny, a common national culture, traditions, etc. Thus, the Russian nation includes not only Great Russians, Belarusians and Little Russians, but also the other peoples of Russia: Georgians, Armenians, Tatars, etc.”

— Konstantin Rodzaevsky, ABC of Fascism

The National Bolsheviks and Left-Eurasianists held a critical view of the remaining White Army factions that continued to oppose the Soviet Union. They saw these groups as mere pawns influenced by foreign agendas and vehemently rejected their assertions that the Soviet government was controlled by Jews or that Jews were responsible for the October Revolution. Both groups had religious inclinations, with the Eurasianists even having contributions from an Orthodox Priest named Georges Florovsky. Despite their support for the new Soviet government, particularly from the National Bolsheviks, their leader Ustryalov faced skepticism and opposition from Vladimir Lenin, who viewed him and his group as reactionary opportunists. Nonetheless, Ustryalov perceived a process of "normalization" unfolding in the Soviet Union and argued that the USSR was increasingly resembling a radish - red on the outside but white on the inside.

When Joseph Stalin assumed power, he permitted Ustryalov and his followers to return to Russia. Although Stalin advocated for socialism in one country and a more nationally-oriented Soviet Union, evident in the adoption of a national anthem, he deviated from early Leninist Soviet policies such as the abolition of the family. Additionally, he banned abortion, criminalized homosexuality, and gradually eased anti-religious persecution during the 1940s. Furthermore, Stalin embraced Russian historical figures during World War II. Nevertheless, due to Ustryalov's open sympathies for Italian Fascism, Stalin maintained a sense of mistrust towards him.

“Russian Bolshevism and Italian Fascism are kindred phenomena, they are signs of an epoch. They hate each other like brothers. They are both messengers of ‘Caesarism’, which sounds somewhere in the distance in the nebulous ‘music of the future.”

— Nikolay Vasilyevich Ustryalov, Under The Sign of The Revolution

Stalin, despite implementing policies that aligned with some of Ustryalov's ideas, ultimately sent him to a gulag in 1937 where he was executed on September 14th of the same year. Many of Ustryalov's followers also faced execution on charges of espionage. While the Eurasianists operated from outside the Soviet Union, by the 1930s, they became disenchanted due to their negligible impact back in Russia. Their legitimacy took a hit when it was revealed that a prominent member, Pyotr Savitsky, was actually an informant for the Soviet authorities. Under the leadership of Nikolai Trubetzkoy and the theological guidance of Father George Florovsky, the group dedicated much of their focus to religious discourse. Trubetzkoy, a key figure in structural linguistics, faced Nazi hostility when he penned a critical piece on Hitler in 1938, an action that prompted a police search of his residence in Germany and is thought to have led to his subsequent stroke under the strain of Nazi oppression.

Some Eurasianists, including General Biskupsky and others, aligned themselves with the German National Socialist ideology, while a few, like Pyotr Savitsky and George Vernadsky, retained their pro-Soviet stance. The left-wing Eurasianists, with figures such as Suvchinsky and Karsavin, merged Marxism with their Eurasianism, embracing internationalism with an Orthodox Christian twist. They envisioned Russia-Eurasia as the future bastion of a global socialist truth, a concept widely dismissed by most Eurasianist thinkers, especially Trubetzkoy, who was firmly opposed to any form of universalism. This ideological rift led to a schism within the movement in 1927, rendering the Marxist-leaning left Eurasianism largely inconsequential.

The left Eurasianists' views mirrored those of the original Russian National Bolsheviks in their strong opposition to Western and liberal ideologies, perceiving Russia as a unique civilization apart from the rest of Europe. They believed Bolshevism was essential for Russia’s transformation and progress. Both groups also sought to establish an empire, albeit under varying guises.

“Historically, National Bolshevist circles distinguished themselves through a staunch orientation toward imperial, geopolitical understandings of the nation. Ustrialov’s adherents and sympathizers, the Left Eurasianists, to say nothing of the Soviet National Bolsheviks, understood ‘nationalism’ as a super-ethnic phenomenon connected with geopolitical messianism, with ‘local development [месторазвитием],’ with culture, with the state on a continental scale. Likewise, with Ernst Niekisch and his German comrades, we encounter the idea of a continental empire ‘from Vladivostok to Flessingue,’ as well as the idea of the ‘Third Imperial Figure’ (‘Die dritte imperiale Figur’). In both cases, we are dealing with a geopolitical and cultural understanding of the nation, devoid of even the slightest hint of racism, chauvinism, or ‘ethnic purity.’”

— Alexander Dugin, Templars of the Proletariat

Throughout the Soviet period, the Eurasianist movement was perceived as a subversive element by Soviet leadership, threatening the established Marxist-Leninist doctrine and the state’s grip on power. Eurasianists' focus on cultural heritage and their connections to nationalist and monarchist factions conflicted with the Soviet Union's commitment to international solidarity and the dismantling of pre-existing class structures. In response, the Soviet state enacted various suppressive tactics against the Eurasianists, including censorship, incarceration, and disinformation efforts. A number of the movement’s leading figures, such as Roman von Ungern-Sternberg, Nikolai Trubetzkoy, Petr Savitsky, Lev Gumilev, Nikolai Ustryalov, Ivan Ilyin, Dmitry Merezhkovsky, Konstantin Rodzaevsky, and Nikolai Berdyaev, were targets of Stalin’s purges, facing execution or death, while others endured persecution, surveillance, and intimidation. The Soviet regime was vigilant against the Eurasianist ideology, aiming to quash any potential threats to its authority or ideological unity.

Another group known as the Union of Mladorossi, led by Alexander Kazembek, shared similar ideals with the Smenovekhovtsy, advocating for a pro-monarchist and anti-Stalinist stance. Despite their opposition to Stalin, they still received support from the Soviet government and even fought alongside the European Resistance against Nazi Germany. Within the Ukrainian Nationalist movements, figures like Mykhailo Hrushevski and Volodymyr Vynnychenko attempted to reconcile Nationalism with Bolshevism. They were given positions within the Ukrainian Communist party and had their newspapers funded by the Soviet government outside of the USSR. This group was often referred to as the "Ukrainian Smenovekhovtsy" by many.