Introduction

As it is known, we published an article addressing Judeo Bolshevism. We’re possibly the only fascist personalities, attempting to discuss the theory without resorting to unreliable data or irrational arguments. Upon releasing our initial article, it became clear that certain aspects needed clarification. Following this, RTSG released a response, which we are now responding to. They mostly sidestepped engaging with our points, opting instead to present nonsensical counterarguments. Our goal is to provide the overlooked nuance and correct the misinformation RTSG has shared. Furthermore, unlike them, we will maintain a professional tone without using any inappropriate language. Now, let's delve into the topic at hand.

Defending The Research of Lynn and Responding to Specific Claims on Jewish Representation

RTSG argues that Lynn’s book alone is insufficient to accurately portray Soviet demography during the early Bolshevik government, highlighting the limitations of relying solely on Lynn's work. Lynn supports his argument with credible sources, citing Yuri Slezkine and further evidence from Russian historians, to argue that a significant Jewish representation of 31% exists alongside an "almost 80% Russian" demographic. The data Lynn used is referenced from Slezkine's work on page 178, with additional citations including works by Beizer, Frenkin, and Menaker. This implies that the evidence, being academically endorsed and well-sourced, cannot be dismissed lightly. Slezkine is a Russian historian and who Lynn draws most of his statistics from. Slezkine’s work has been praised by many academics and his statistics that he documented in his book also come from historians with professional credentials. To handwave these sources away is extremely disingenuous.

RTSG states:

“What this means is that the mere presence of Trotsky in a leading position cannot by itself be a kind of Jewish ingroup preference or “conspiracy” directly influencing the Bolshevik party as Zoltanous has claimed.”

Where have we suggested a conspiracy? Our initial analysis clarified that Jews were disproportionately represented and played a crucial role within the early Bolsheviks, forming an elite segment within the USSR. The accusation of proposing a conspiracy is unfounded and misrepresents our argument. RTSG challenges Lynn's assertion that 40% of a certain group were represented, yet offers no proof to counter the claim. Rather than addressing this directly, the conversation is redirected towards the Council of People's Commissars, with a diminished focus on Trotsky's role. Nonetheless, RTSG appears to concede on some points.

“Our argument, rather, is that the mere presence of an individual ethnicity inside the Bolshevik’s upper echelons does NOT constitute ‘control.’”

Well, we aren’t claiming nor did we ever believe the Bolsheviks were controlled by Jews or the Bolsheviks were involved in some international Jewish Conspiracy. What we are claiming is that Jews were overrepresented in high up positions in the early Bolshevik era and were a notable elite group in the USSR, something RTSG does not dispute.

“Again, the mere existence of Jews in positions of power does not demonstrate that they are the majority or any notable portion of the Soviet Union’s total power structure. To reiterate again, Zoltanous must bring direct evidence to substantiate a claim of a Jewish in-group conspiracy in the Soviet Union by demonstrating that the majority of the Soviet Hierarchy was dominated by Jews.”

The presence of Jewish individuals in early Soviet leadership raises questions about their representation within the Soviet power structure. We're not suggesting a conspiracy but highlighting their significant roles, as demonstrated in instances like Sverdlov's contributions. The debate over Kamenev's Jewish identity seems misplaced; whether or not he strictly adhered to Jewish law matters less than the influence and identity he chose to embrace, as evidenced by his actions and affiliations, including his marriage to Olga Davidovna Bronshtein and support for Jewish cultural events and Zionism in the Soviet Union. Addressing the claim that a mere 25% representation is inflated, even reduced estimates of 19% or 14% suggest a disproportionate representation of Jews in Bolshevik ranks, contradicting arguments of their minimal influence. Furthermore, the critique of the photograph analyzed by Vicksburg misses the broader point: it's not about proving Lenin was controlled by Jews, but about acknowledging their significant presence and influence within the Bolshevik movement, a stance supported by the lack of counterarguments to the notion of Jewish overrepresentation.

Lenin's noticeable emphasis on Jews over other ethnicities suggests a nuanced view on his attitudes. The argument that his focus was on countering Russian Chauvinism rather than harboring disdain for Jews resonates with our viewpoint. Dismissing Kevin Macdonald as a fraud prematurely, despite ongoing debates and varied responses challenging this notion, appears hasty. The conflicting accounts regarding Jewish presence in the Politburo, with estimates ranging from 40-60%, are based on data from this article. The chart indicates that Jewish representation in the Politburo was between 40-60% from 1917 to 1924, yet this article appears to challenge this data. Similarly, claims about our depiction of the Holodomor and Kaganovich's views on Judaism oversimplify the complexities of historical figures' beliefs and actions. Arguments refuting Sverdlov's role in the Tsar's assassination disregard significant evidence and contradict historical accounts. Moreover, the assertion that our article suggests a "Jewish ritual murder" misinterprets our stance. Lastly, criticisms of the involvement of Jewish neoconservatives in the Iraq War fail to acknowledge the nuanced roles certain individuals, not representative of all Jews, played in its initiation. When examined critically, it clearly aligns with a pro-Jewish position, as noted by Jim Lobe's speech at the conference Israel’s Influence: Good or Bad For America on March 18, 2016.

Our analysis aims to offer a nuanced perspective on Jewish participation in early Soviet history and politics, avoiding conspiracies or simplifications by recognizing the diverse roles and identities of Jewish individuals in shaping that era. He also cites Anthony Sutton as a counterargument to our stance on Jews; however, within the same quote, it acknowledges their involvement. This quote mainly rebuts a singular conspiracy theory, which is not the argument we put forth. To reassert the higher presence of Jewish individuals in the Bolshevik party, we will draw upon the insights of the Polish historian Benjamin Pinuks.

“In April 1917, three of the nine members [33%] of the Central Committee were Jews: Kamenev, Zinovyev and Sverdlov. In August of that year, six of the twenty-one [28%] members of the Central Committee were Jews: Kamenev, Sokolnikov, Sverdlov, Zinovyev, Trotsky and Uritsky.”

— Benjamin Pinuk, The Jews of The Soviet Union

Jewish overrepresentation in the Soviet Union can further be established by more statistics by Slezkine.

“When the Society of Militant Materialist Dialecticians was founded in 1929, 53.8 percent of the founding members (7 out of 13) were Jews; and when the Communist Academy held its plenary session in June 1930, Jews constituted one-half (23) of all the elected full and corresponding members. At the First Congress of Soviet Writers in 1934, Jews made up 19.4 percent of all delegates.”

— Yuri Slezkine, The Jewish Century

Why Trotsky Is Important

RTSG asserts that Trotsky, despite being a secular assimilationist who distanced himself from his Jewish heritage and aligned more with Russia, was actually hostile towards many Jews. This irony is highlighted in juxtaposition to Trotsky's historical stance against anti-Semitism, as noted by Joseph Nedava’s Trotsky and The Jews. Although Trotsky was not religious and did not speak Yiddish, he recognized his Jewish roots. He mingled with numerous Jews and, during his time in New York, contributed to the Yiddish pro-Zionist newspaper Forward and frequented Jewish cafes. Following the ascent of Nazi Germany, Trotsky increasingly identified with Jewish causes, condemning assimilation and proposing a national resolution to the Jewish Question.

“Once embraced as the only acceptable solution to antisemitism, Trotsky came late in his life to reject assimilation as a programme for the Jews as a people. (Of course, he continued to support assimilation as an option for an individual, to be pursued or not according to their own lights.) 'During my youth, he wrote in 1937, 'I rather leaned toward the prognosis that the Jews of different countries would be assimilated and that the Jewish question would thus disappear, as it were, automatically. The historical development of the last quarter of a century has not confirmed this view. Chastened, Trotsky declared that not even a socialist democracy' would 'resort to compulsory assimilation.

In this, history had been Trotsky's teacher. 'He admitted that recent experience with antisemitism in the Third Reich and even in the USSR had caused him to give up his old hope for the ‘assimilation’ of the Jews with the nations among whom they lived;, recalled Deutscher. Traverso concurs: Trotsky became 'convinced of the necessity of a national solution to the Jewish problem' because he became 'conscious of the impasse into which assimilation had entered.”

— Alan Johnson, Leon Trotsky’s Long War Against Anti-Semitism

RTSG shares a source indicating Trotsky overlooked pogroms that occurred during the civil war. However, this is not a comprehensive portrayal. According to the The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe:

“The Red Army, under the direction of Leon Trotsky, was specifically charged not to attack Jewish populations, and indeed Soviet troops are blamed for only 9 percent of the pogroms. Furthermore, statistical evidence indicates that pogroms perpetrated by Red Army troops were milder in nature: whereas an average of 38 people were murdered in every Ukrainian pogrom, and 25 people per White Army pogrom, only 7 people were killed in the typical Red Army pogrom.”

— The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews In Eastern Europe

Trotsky's failure to halt or his minimal attention to pogroms perpetrated by the Red Army stemmed from their infrequent occurrence and, when they did happen, they were significantly less violent compared to those carried out by the White Army or by individuals acting alone.

Why Soviet Collectivization Was Bad

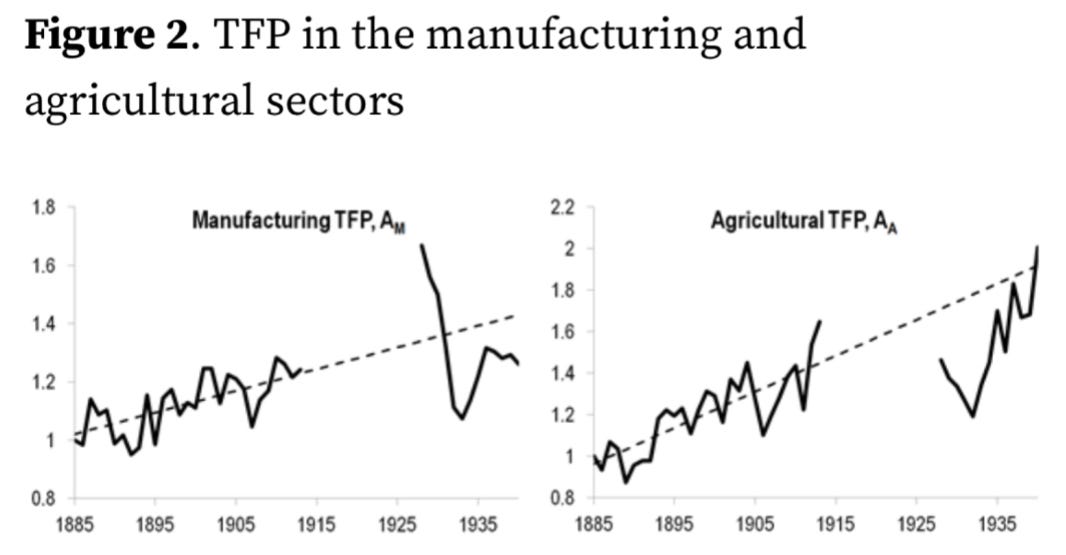

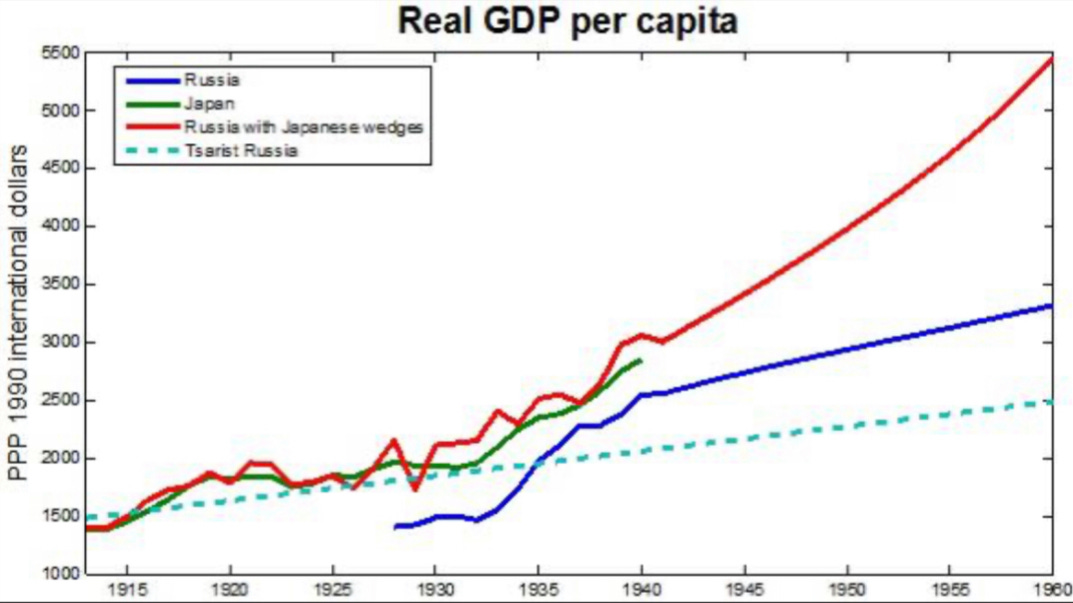

RTSG controversially defends the stance that the Holodomor was not harmful and asserts that collectivization was a success, a claim that many find absurd. He accuses critics of falsehoods, yet evidence suggests otherwise. Against RTSG's assertion that Stalin's collectivization boosted living standards significantly, academic research, such as the economic study Stalin and Soviet Industrialisation by A. Tsyvinski and colleagues, contradicts this. The study questions the effectiveness of Stalin's policies, indicating that, due to a significant decline in agricultural production and a stagnant GDP, agricultural and manufacturing productivity under Stalin remained well below historical trends. This evidence challenges RTSG's narrative of Stalin's economic policies and their supposed success.

The study found that Stalin's economic policies from 1928 to 1940 led to substantial welfare losses, estimating a 24% reduction in aggregate consumption compared to potential outcomes based on pre-1913 growth trends. Comparative analyses with Japan and a hypothetical continuation of the New Economic Policy (NEP) suggest that Soviet citizens would have been better off without Stalin's drastic shift in economic direction, highlighting the detrimental impact of his policies.

Moreover, the research referenced in our previous critique challenges the notion that the famine in Ukraine resulted from natural causes or livestock slaughter, instead attributing the severity of the famine to anti-Ukrainian biases. It provides data showing that regions with higher percentages of ethnic Ukrainians had higher death rates, irrespective of grain production levels. This suggests a deliberate bias against Ukrainians rather than just agricultural setbacks. RSTG did not address this specific study, which we concede highlights an anti-Ukrainian bias contributing to the Ukrainian famine. RSTG's defense of the Holodomor and the supposed popularity of collectivization lacks substantial evidence, especially when historical records indicate widespread resistance, including numerous peasant uprisings. This contradicts claims of broad support for Stalin's policies, emphasizing the need for compelling evidence to challenge the research's conclusions and reassess the impact and reception of Stalin's economic strategies.

“[The] head of political education in the Red Army, delivered a powerful speech. He declared that the situation created because of the policy of “liquidating the kulaks” and of agricultural collectivisation to the bitter end, demanded by Stalin, had given rise to an incurable discontent amongst the soldiers. In large part the sons of peasants, they did not conceal their resentment of the Soviet Government. Thus either the system changed or they would no longer be able to count on the Red Army. “

— Jonathan Haslam, Soviet Foreign Policy, 1930-33: The Impact of The Depression

During a meeting, Stalin initially stayed silent but later pushed the Politburo to address the criticisms raised. While seven members disagreed with Stalin's stance, only Stalin and Molotov supported it. Stalin then took a day to reflect and crafted the "Dizzy with Success" speech independently, leading to a halt in the forceful collectivization drive, indicating its unpopularity. Collectivization served dual purposes: to accumulate capital for industrial advancements and to suppress Ukrainian nationalism. Despite achieving its goals, the approach could be seen as complicity in genocide, overlooked due to the war with Nazism. Academics like Mark Tauger and Stephen Wheatcroft also argue that the economic policies worsened the famine, suggesting either incompetence or deliberate actions, even without invoking the genocide accusations. Essentially, collectivization faced disapproval not only from the Kulaks but also from peasants at large and was not favored within the military. Rationalizing this from a pragmatic standpoint would entail acknowledging a disregard for human life, a frequent critique of communists that RTSG refrains from saying out loud. This underscores the ruthless approach often associated with communists.

The Pivot to Imperial Japan and Hitler’s Supposed “Collaboration” With Trotsky

In response to my previous article, RTSG made a striking claim that Trotsky collaborated directly with Japan and Germany against the Soviet Union. However, this assertion lacks substantiation from primary sources or reputable historians, apart from Grover Furr, a controversial figure known for absolving Stalin of any wrongdoing. Furr, a former English professor turned Stalinist, garners support from online Marxist-Leninists who view him as reliable. Nevertheless, a critical analysis of Furr's arguments highlights significant flaws in his reasoning. Furr contends that the Katyn Massacre was orchestrated by the Nazis, citing the discovery of Nazi-related artifacts at the site. Yet, these items were found in a separate layer from the actual grave, suggesting no direct link to the victims. Moreover, the German-origin bullets uncovered were compatible with firearms used by various nations at that time, casting doubt on the Nazis' sole culpability. Despite acknowledgments from Soviet and Russian authorities regarding their involvement in the Katyn massacre, Furr controversially dismissed a document released by Russia in the early 2000s, purportedly signed by Stalin, as a forgery without presenting compelling evidence. It is unlikely that contemporary Russia, which opposes demonizing Stalin, would fabricate such a document. The preponderance of historical evidence points to Soviet responsibility for the atrocity. Furr's assertion that the Moscow Trials were not tampered with has been widely debunked by historians, with substantial evidence indicating that coerced confessions were extracted through torture. Furr's selective methodology and unsubstantiated claims undermine his credibility, leading to his viewpoints being largely marginalized within the historical community. When discussing Soviet history, it is prudent to steer clear of Furr's work, as his contentious viewpoints align more closely with controversial figures like David Irving than with reputable scholars.

Furr's sources alleging Trotsky's collaboration with Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan rely heavily on secondhand conversations, and interviews, rendering them as lacking in substantiation. This narrative lacks validation from historians and primary sources like official documentation. Secondhand conversations, and interviews should only be relied upon if they can be corroborated by documents, which he failed to do. This essentially calls the entire argument into question. Thus, the claim of a direct link between Trotsky, Japan, and Germany is essentially fictional and serves particular political agendas. The fundamental question arises: Which scenario is more credible? Is it easier to believe that a Jewish Marxist pivotal in the first successful workers' revolution, openly opposing fascism, was secretly a Nazi collaborator? Or is it more plausible that Stalin who exiled him, expunged him from historical records, and potentially orchestrated his assassination was engaged in deception? Furr often references archives without providing accurate interpretations when citing other historians. This discussion should transcend ideological biases, and while there may be legitimate reasons to critique Trotsky, Marxist Leninists should refrain from engaging in such pseudo-historical narratives. What baffles me the most in all of this is Furr's acknowledgment of lacking evidence yet asserting that it somehow bolsters the conspiracy.

Why bring up this issue without substantial evidence? It's clear that RTSG employed a Gish Gallop pivot, diverting attention from the broader argument. The Gish Gallop, named after creationist Duane Gish, involves overwhelming opponents with a rapid succession of half-truths, misrepresentations, and false claims in a debate. The strategy is to bombard the opponent with numerous arguments, making it difficult for them to address each effectively within the time constraints of a debate. This tactic aims to create confusion, sow doubt, and hinder the opponent's ability to respond adequately. However, I am going to humor him and respond to all of these claims.

The Pivot From Soviet Zionism to Hitler and Mussolini’s Zionism

In his article Religion or Nation? published in Il Popolo di Roma in 1928, Mussolini conveys his bewilderment regarding the religious and racial aspects of Jews. He contends that this ambiguity leads to numerous contradictions between the Italian identity and the Zionist identity.

Mussolini says this:

“We then ask the Italian Jews: are you a religion or are you a nation? This question is not intended to give rise to anti-Semitic riots, but merely to bring to light a problem which I know exists, and which is useless to further ignore.”

— Benito Mussolini, Religion or Nation?

In his article The Zionists, published in Il Popolo di Roma on December 16th, 1928, Mussolini articulates his objectives and genuine intentions concerning Jews. He argues that individuals of Jewish descent who do not harbor genuine affection for Italy or exhibit opportunistic loyalty cannot be considered truly Italian. Mussolini notes the disparity in Jewish authority between Italy and Germany, indicating the need for a context-specific approach to addressing the Jewish question. He goes as far as condemning Zionism as an international phenomenon that runs counter to Italian values. Mussolini's aim was to spark introspection among Italian Jews and raise awareness among the broader Italian populace.

The passage concludes with Mussolini's statement:

“A Jewish problem exists, and it is no longer confined to that shadowy sphere.”

— Benito Mussolini, The Zionists

Mussolini did not plan to create ghettos, provoke pogroms, or carry out the extermination of Jews. Instead, his strategy involved the gradual expulsion of Jews from Italy, allowing ten individuals to leave each day. He briefly aligned with the Zionist movement, a stance akin to Hitler's approach. However, Italy's participation in World War II led to the abandonment of this plan, with Jews being presented with the option of engaging in high-value currency transactions. As a result, only 6,000 Jews opted to depart, while the rest faced years of discrimination during the Fascist rule, with a significant portion ending up interned in concentration camps. However, due to its nuanced nature, this topic is not covered by RTSG.

German policymakers backed Zionist endeavors as they viewed Zionism as a valuable tool for their foreign policy objectives. In the 1930s, the Nazis continued this support to leverage Zionism and appease the British. Shortly after coming to power in 1933, the Hitler administration entered into the Haavara Transfer Agreement with Zionist representatives, aiming to combat unemployment and agricultural issues in Germany while also encouraging Jewish emigration. This agreement facilitated the departure of many Jews and boosted German exports to Palestine and the Middle East, undermining the global boycott on German goods. While non-Zionists opposed the Haavara Agreement, many Zionists believed that emigration to Palestine was the sole solution given the dire situation for Jews in Germany. Despite internal divisions among Zionists, the pragmatic faction accepted the Haavara Agreement to save Jewish lives, leading to a surge in German exports to Palestine by 1937. The Peel Partition Plan of 1937 eventually prompted a reevaluation of German policy towards Palestine, impacting both Nazi and Zionist interests. Palestinian Arab leaders, notably Haj Amin al-Husayni, the Mufti of Jerusalem, openly expressed pro-German sentiments, prompting a shift towards backing the Arab side.

“The Arab Freedom Movement in the Middle East is our natural ally against England.”

— Adolf Hitler 23 May 1941

“Germany stood for uncompromising war against the Jews. That naturally included active opposition to the Jewish national home in Palestine, which was nothing other than a center, in the form of a state, for the exercise of destructive influence by Jewish interests. This was the decisive struggle; on the political plane, it presented itself in the main as a conflict between Germany and England, but ideologically it was a battle between National Socialism and the Jews. It went without saying that Germany would furnish positive and practical aid to the Arabs involved in the same struggle, because platonic promises were useless in a war for survival or destruction in which the Jews were able to mobilize all of England's power for their ends.... the Fuhrer would on his own give the Arab world the assurance that its hour of liberation had arrived. Germany's objective would then be solely the destruction of the Jewish element residing in the Arab sphere under the protection of British power. In that hour the Mufti would be the most authoritative spokesman for the Arab world. It would then be his task to set off the Arab operations, which he had secretly prepared. When that time had come, Germany could also be indifferent to French reaction to such a declaration.”

— United States, Documents on German Foreign Policy 1918–1945

Some German policymakers begin contemplating relocating Jewish populations to Madagascar. This notion gained traction as a potential solution, with Germany proposing to maintain control over this proposed settlement. However, this plan was also ultimately discarded as Germany redirected its focus towards the East and implemented the Final Solution. This leads us to the discussion of Soviet support for Zionism. The Soviet ideological position regarded Zionism as a type of bourgeois nationalism, with Vladimir Lenin condemning it as regressive and reactionary, eroding class distinctions among Jews. Joseph Stalin's pivot to a pro-Zionist foreign policy from late 1944 aimed at fostering a socialist and pro-Soviet Jewish state to weaken British influence in the Middle East, as noted in Paul Johnson's A History of the Jews. This shift led the Soviet Union and other Eastern Bloc nations to support the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine in November 1947, setting the stage for Israel's formation.

“In the debate preceding the decision to establish it, many delegates, and especially the Soviet delegate, expressed their sympathies with the Jewish case. Until November 29th, this would continue to be a pressing issue for the United Nations.”

— Nechemia Ben-Tor, All-Out War: From The Death of The Jewish Resistance Movement to The United Nations Resolution

Despite officially recognizing Israel on May 17, 1948, just three days after its independence declaration, the Soviet Union, as the first to grant de jure recognition, eventually returned to an anti-Zionist stance due to Israel's growing ties with the United States. This brings us to the emergence of a pivotal Israeli faction, Lehi. Originating as a splinter group from the Irgun militant organization in 1940, Lehi was formed to sustain resistance against the British during World War II. Initially exploring potential alliances with Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, Lehi perceived Nazi Germany as a lesser threat to Jewish interests compared to Britain. Despite two unsuccessful attempts to collaborate with the Nazis and propose a Jewish state rooted in nationalist and totalitarian ideals aligned with the German Reich, the group's direction shifted following Stern's death in 1942. Under new leadership, Lehi gradually turned towards endorsing the Soviet Union led by Joseph Stalin, as outlined by Sasson Sofer in Zionism and The Foundations of Israeli Diplomacy. Post-1942, the organization evolved into a blend of Marxist-Leninist ideology and messianic Jewish nationalism, drawing parallels to the Labour Zionism of Moses Hess.

“A key element was “Soviet orientation.” Lehi believed that after World War II, the Soviet Union was a natural ally. Soviet opposition to Zionism, they believed had been due to the Jewish youth abandoning Communism for Zionism, so that the latter had been seen as an instrument of British imperialism, which the Soviets opposed in Asia. Lehi believed that since this was no longer true after the war, the conflicting interests between the two empires made the Soviets their natural allies.”

— Nechemia Ben-Tor, All-Out War: From The Death of The Jewish Resistance Movement to The United Nations Resolution

Following the declaration of independence by Israel, the Lehi central committee declared its endorsement for Jewish sovereignty in the liberated regions of the homeland. They highlighted the belief that an increase in Jewish control would enhance national cohesion. The group pledged to carry out all civic responsibilities towards the State of Israel and its military. Eventually, Lehi transitioned its allegiance from the Soviet Union to the United States due to Israel's deepening partnership with the U.S. and the waning support from the Soviet Union. As a result of this shift, some members went on to play a role in the establishment of the Israeli Communist party. Upon delving into the intricacies of this subject, it becomes evident that it resembles more of a geopolitical poker game rather than the straightforward black-and-white ideological narrative portrayed by RTSG.

The Pivot From Soviet Funding to Hitler and Mussolini’s Funding

The conversation's pivot to the financial aid provided by the Soviets to Hitler and Mussolini could be seen as a tacit acknowledgment, given RTSG's lack of rebuttal to the argument and evidence highlighting Germany's significant financial support to the Bolsheviks. Additionally, RTSG's emphasis on challenging Sutton's assertions regarding Jacob Schiff and the idea of a "Jewish Conspiracy" overlooks the main issue. We agree that the concept of a single conspiracy is unfounded, and we draw upon Antony Sutton's work to demonstrate that figures like Olof Aschberg and capitalists such as William Boyce Thompson also contributed financially to the communists. Our explanation for why capitalists might back the Bolsheviks, which RTSG did not respond to, stands as an implicit agreement by omission. Although RTSG mentions British financial support for Mussolini, this acknowledgment leads us to examine the motives behind such backing more closely. Previously, we discussed foreign investments in the Bolsheviks as a strategy to create internal turmoil in Russia and to expedite its exit from World War I, thereby aiding Germany. Consequently, we must question the specific reasons behind British support for Mussolini. The aim was clear: to motivate Italy to join the First World War on the side of the Allies against the Central Powers. Peter Martland of Cambridge University and historian Christopher Andrew have documented Britain's financial assistance to Mussolini in 1917, which amounted to 100 pounds weekly — about $9,600 in current value. This funding is noteworthy, especially considering Mussolini's ownership of the Il Popolo d'Italia newspaper, which was instrumental in promoting Italy's alliance with the Allies during the war.

"The last thing Britain wanted were pro-peace strikes bringing the factories in Milan to a halt. It was a lot of money to pay a man who was a journalist at the time, but compared to the 4 million pounds Britain was spending on the war every day, it was petty cash, I have no evidence to prove it, but I suspect that Mussolini, who was a noted womanizer, also spent a good deal of the money on his mistresses.”

— Peter Martland quoted in Recruited by MI5: the name’s Mussolini. Benito Mussolini by Tom Kington

It should also be highlighted that according to documented evidence, the funding Mussolini received had no influence on his ideological beliefs, as pointed out by his biographer in Mussolini: A New Life:

“As the 1919 police report on Mussolini and Fascism concluded, Mussolini’s volte-face was not the result of ‘calculated interest or money’ but of his being ‘a sincere and passionate apostle first of vigilant armed neutrality, then of war.”

— Nicolas Farrell, Mussolini: A New Life

Mussolini's $100 million loan from JP Morgan in 1927 initially aimed to address Italy's immediate economic crisis but also signaled a move towards financial independence by refusing further foreign loans.

"In 1926 Mussolini first intervened in the banking sector by granting the Banca d’Italia jurisdiction over the issue of bank notes and the management of minimum requirements for bank reserves, including gold. This formed part of his policy of using Italian fascism 'primarily to create an autarkic state not subject to the vagaries of world trade and finance.' In 1927 Italy received a loan from JP Morgan of $100 million to meet a special emergency. Thereafter Mussolini refused 'to negotiate or accept any more foreign loans', as 'he was determined to keep Italy free from financial subservience to foreign banking interests.' In 1931 the State arrogated to itself the right to supervise all major banks by means of the Istituto Mobiliare Italiano (Institute of Italian Securities). In 1936 the process was completed when, by means of the Atto Reforma Bancaria (Banking Reform Act), the Banca d’Italia and the major banks became state institutions. The Banca d’Italia was now a fully fledged state bank which had the sole right to create credit out of nothing and advance it for a nominal fee to other banks. Limits on state borrowing were lifted (as was the case with the Bank of Japan see infra) and Italy abandoned the gold standard."

— Stephen Mitford Goodson, A History of Central Banking and The Enslavement of Mankind

So, when placed in the appropriate context, the initial funding Mussolini received was primarily for geopolitical reasons. Subsequently, the laon aimed to tackle the banking crisis and invigorate the Italian economy, facilitating the pursuit of autarky. According to the evidence, neither instance altered Mussolini's ideological stance, which remained in alignment with his original ideas and views. This scenario bears resemblance to the funding of the Bolsheviks during the Russian Civil War, which was not the result of secretive manipulations by financial capitalists. This highlights the nuanced reality that politics is seldom a matter of clear-cut distinctions.

“Fascism never served the interests of Italian business… there is no credible evidence that Fascism controlled the nation's economy for the benefit of the 'possessing classes.'“

— A. James Gregor, The Search For Neofascism: The Use and Abuse of Social Science

Naturally, I wouldn't expect Marxist Leninists to appreciate nuance, as they often see things in black and white. This lack of complexity is precisely why their arguments are seldom taken seriously by those with academic credentials. The accusations directed at Italian Fascism have also been applied to Nazism, but these allegations lack substantial evidence. Henry Turner delves into these assertions by stating:

“To What extent did the men of German big business undermine the Weimar Republic? To what extent did they finance the Nazi party and use their influence to boost Hitler into power? As should be evident by this point the answer in both cases is a great deal less than has generally been believed. Only through gross distortion can big business be afforded a crucial or even a major role in the downfall of the republic.

The early growth of the NSDAP took place without any significant aid from the circles of large-scale enterprise. Centered in industrially underdeveloped Bavaria, tainted with illegality as a consequence of a failed beer hall putsch of 1923, saddled with a program containing disturbingly anti-capitalist planks and amounting only to a raucous splinter group politically, The NSDAP languished in disrepute in the eyes of most men of big business throughout the latter part of the 1920s. The major main executives of Germany proved with rare exception resistant to the blandishments of Nazis including Hitler himself, who sought to reassure the business community about their party’s intentions. Only the electoral breakthrough of 1930, achieved without aid from big business drew attention to it from that quarter. From The Development and Character of the Nazi Political Machine, 1928-1930, and the Nsdap Electoral Breakthrough; After weighing all the evidence. We must recognize that the financial subsidies from industry were overwhelmingly directed against the Nazis. Bulk of the funds in the party treasury came from membership dues.”

— Henry Turner, German Big Business and The Rise of Hitler

Upon reflecting on the perspectives of Peter Drucker, it becomes evident that the idea of large corporations promoting Fascism is unfounded. Contrary to popular belief, in Italy and Germany, the industrial and financial sectors showed minimal support for Italian Fascism. Additionally, the notion that big businesses thrive under Fascist regimes is misguided; in reality, the business class often faces significant disadvantages within the confines of a totalitarian and wartime economy. Further exploration of this subject can be found in the dated yet insightful analysis by James Pool and Suzanne Pool, which examines the financial foundations of Hitler's ascension to power.

“The party's financial substance was however made possible not just by the donations of the most generous contributors but by the day-to-day income from the average members. Every member of the party was expected to pay his dues of one Mark per month and give whatever his means would permit, but since many of them were unemployed there was very little surplus income. You have no idea Hitler later told Gregor Strasser ‘what a problem it was in those days to find the money to buy my ticket when I wanted to deliver a speech at Nuremberg.’

Looking back at the financing of Hitler’s political activities from 1918 to 1923 one thing is particularly interesting. Many historians have contended that the National Socialist Party was financed and supported by big business? Yet as has been seen only two of Germany’s major industrialists Fritz Thyssen and Ernst von Borsig gave anything to the Nazi party during these early years. Donations came from some conservative Munich businessmen who were at the height of the communist danger as well as small Bavarian factory owners like Grandel, the Berlin piano manufacturer Bechstein and the publisher Lehmann. But none of these men despite their wealth could fit properly in the category of big business.

There is no evidence that the really big industrialists of Germany such as Carl Bosch, Hermann Biicher, Carl Friedrich von Siemens, and Hugo Stinned or the great families such as the Krupps and the leading bankers and financiers gave any support to the Nazis from 1918 to 1923. Indeed few of them knew this small party from Bavaria even existed. Most of Hitler’s donations came from wealthy individuals who were radical nationalists or anti-Semites and contributed because of ideological motivation. To a certain extent the wealthy white Russians fit into this category; they could also be looked on as the only real interest group that hoped to gain a definite political-economic objective from their aid to the Nazis.”

— James Pool and Suzanne Pool, Who Financed Hitler

In Sutton's work, it is established that there is no connection between the Nazis and the Rothschilds or the royal family. Historian Richard J. Evans, in The Coming of The Third Reich, highlighted that the Nazis' rise was fueled by grassroots financial support, distancing themselves from major corporate and bureaucratic entities such as big businesses or trade unions. This challenges the communist propaganda suggesting that capitalist interests funded the Nazis, dismissing it as historically inaccurate. Rather than focusing on whether Hitler received financial support, it's crucial to explore if such backing influenced his beliefs. Historical scrutiny reveals that Hitler remained devoted to his goals and maintained control over his movement, regardless of funding. There's little evidence to suggest that financial transactions swayed Hitler's decisions; he wielded political power irrespective of his financial supporters' expectations. This perspective might also apply to Mussolini and potentially even Lenin, with consideration of Sutton's research. The talking points used here lack credibility and historical accuracy, failing to garner serious attention from any scholars in history, political science, or economics. RTSG's discourse, like Haz closely resembles that of Second Thought or Hakim, showing a similarity with the Regressive Woke Left in their perspectives on the national question, history, fascism, the right wing, and their sacrilegious views on Christianity and the Russian Tsar St. Nicholas II.

Conclusions

Marxism, tracing its lineage to Karl Marx, has long been interwoven with Jewish intellectual heritage. Notably, Moses Hess, a pivotal figure in Labour Zionism, reportedly exerted a profound influence on Marx's ideological framework, even playing a crucial role in Engels' conversion to communism. This association underscores a Messianic Jewish vision of communism as a utopian Heaven on Earth. Marx championed Jewish integration and liberation within broader societies, aiming to dismantle prevalent norms across European Christian and Jewish religious cultures. Kevin Macdonald argues that Marxism is a protective bastion for secular Jewish interests, offering a critical lens for societal transformation. Addressing concerns of "overrepresentation," the proportional status of Jews aligns closely with their socio-economic standing, intelligence, and educational achievements. Jerrold Seigel, in Marx's Fate, highlights Marx's positive rapport with Jewish communities, citing his relationships with prominent Jewish figures like Heinrich Heine and Ludwig Kugelmann. Furthermore, Isaac Deutscher, in The Non-Jewish Jew, suggests that Marx and other influential figures belonged to a secular Jewish tradition, viewing universal liberation through a distinctive Jewish lens. Deutscher emphasizes the exceptional nature of these individuals, dwelling at the crossroads of diverse civilizations, religions, and national cultures.

Jewish individuals were notably overrepresented and held pivotal positions in shaping the Bolshevik party and the evolution of the USSR, as emphasized in the substack that served as a key source for RTSG.

“It’s undoubtedly true, as we’ll see, that among early Bolshevik elites Jews were substantially overrepresented.”

— Mischling Review, Judeo-Bolshevism: Fact From Fiction

RTSG heavily borrowed sources and arguments from the Mischling Review, with clear instances of plagiarism. Had they scrutinized the material closely, they would have encountered the quotation provided, directly undermining their entire stance. While some sources are commendable, the bulk of the content appears to be misappropriated and reveals a misunderstanding of statistics. Moreover, the lack of proper source citation in their work demonstrates a glaring lack of professionalism. Furthermore, Lynn's sources on Bolshevik matters align with academically endorsed materials. Brendan Simms, a historian who studied Hitler, noted that the anti-Semitic idea of Judeo-Bolshevism suggested that the Bolsheviks were not authentic socialists but capitalists. This concept insinuates that Jewish finance capitalists are using fake socialism to undermine proletarian nations, although this underlying implication may not be fully understood by more vulgar anti-Semites.

“I think that for some time now they have been laughing on the other side of their face. Today I will once more be a prophet. If the international Jewish financiers, inside and outside Europe, succeed in plunging the nations once more into a world war, then the result will not be the Bolshevization of the earth, and thus the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe!“

— Adolf Hitler Reichstag Prophecy speech, January 30, 1939

Nevertheless, it remains clear that this fundamentally depicts an anti-capitalistic viewpoint. According to socialist philosopher Sidney Hook, anti-Semitism was prevalent across various forms of socialism. In 1943 in occupied Paris, Léon Degrelle, a key National Socialist figure, stressed that the war, including the fight in Russia, was driven by the socialist aspect of fascism. Underscoring the aim of instigating a true socialist revolution through the conflict.

“Very simple, then, is the emotional complex underlying socialist racism. For we are in the presence of a social idea, of a socialism, whose motive lies not in the need to achieve justice for the Germans, as men who are deprived of well-being by an unjust economic regime, but rather in the idea of achieving for Germany, as a people, as a race, as a living unit, the best and most just social regime. Therefore, the anti-capitalism of the Hitlerite is different from the anti-capitalism of the Marxist. He sees in the capitalist regime not only a certain system of economic relations, but he also sees the Jewish one, adding a racist concept to the strict economic concept. The anti-Jewish idea and the anti-capitalist idea are almost the same thing for National Socialism. And the thing is that, as we have said, the German objectifies his particular problem in Germany, and his socialist concern pursues at all times an order for the benefit of the entire race.”

— Ramiro Ledesma Ramos, Racismo socialista en Alemania

The anti-Semitic core of Nazism was primarily a reflection of anti-capitalist sentiments. Even though Stalin removed ethnic Jewish elements from Bolshevism, Hitler observed in his second book that its messianic worldview still carried a Jewish essence, preventing it from embracing genuine national anti-capitalism. Consequently, he believed Bolshevism could never authentically become Russian. Given the lack of substantial backing for RTSG’s views, it appears appropriate to conclude our article here.

Found this fascinating. So comprehensive I've subscribed. Look forward to new learning. Thanks.