"Our leader has dared to unmask the Jews. To demonstrate to the people all the harshness of their bad faith... their arts of capitalist exploitation. As the vampires of humanity, the exploiters of humanity!"

— Robert Ley, 1945 last speech

Is National Socialism Capitalism In Decay?

In exploring the dynamics between National Socialism and Capitalism, discussions often delve into diverse viewpoints regarding Hitler's practices and ideologies. It is widely noted that Hitler primarily focused his aggression on Bolshevism, which the NSDAP labeled as "Jewish Bolshevism." As a result, some contend that the lack of overt anti-capitalist sentiment in Nazi ideology and the benefits extended to industrialists during their regime suggest a compatibility with Capitalist principles, especially after the expulsion of the movement's left-wing elements during the Night of the Long Knives. Yet, it is essential to understand that this interpretation oversimplifies the issue and overlooks the significance of the broader historical narrative, including the Night of the Long Knives. It's misleading to consider this event as a one-off deviation that occurred without Hitler's consent.

“Much had in fact happened that unsettled Hitler. Göring had wantonly liquidated Gregor Strasser, Hitler’s rival, and there had been a rash of killings in Bavaria... Hitler’s adjutant Brückner later described in private papers how Hitler vented his annoyance on Himmler when the Reichsführer SS appeared at the chancellery with a final list of the victims eighty-two all told. In later months, Viktor Lutze told anybody who would listen that the Führer had originally listed only seven men; he had offered Röhm suicide, and when Röhm declined this ‘offer’ Hitler had had him shot too. Hitler’s seven had become seventeen, and then eighty-two.”

— David Irving, The War Path

Additionally, the analysis by A. James Gregor, an expert on Fascism, reveals a complex interplay between Fascist movements and Capitalism, often not apparent in public discourse. This complexity is stark in Germany, where Fascism arose in an already industrialized context, unlike in nations like Italy, Argentina, and Iraq, where Fascism played a role in driving industrialization. Stanley G. Payne, another esteemed historian, echoes Gregor's findings and provides an in-depth examination of Capitalism's role and influence during Hitler's rise to power.

“Hitler worked during 1931–32 to establish ties with influential sectors of society, cooperating part of the time with the right and trying to reassure businessmen that they had no reason to be apprehensive of Nazi “socialism.” Yet despite massive leftist propaganda that Hitler was the paid agent of capitalism, Hitler garnered only limited financial support from big business. While there was considerable support for Hitler among small industrialists, most sectors of big business consistently advised against permitting him to form a government. The Nazi Party was primarily financed by its own members."

— Stanley G. Payne, A History of Fascism

To gain a deeper understanding of the nexus between Capitalism and the emergence of the NSDAP, Henry Ashby Turner's scholarly book German Big Business and The Rise of Hitler is invaluable. It meticulously explores the financial underpinnings of the Nazi party, effectively challenging the long-held notion that Fascism or Nazism was Capitalism's last-ditch effort to stave off collapse.

In dissecting the rise of the Nazi party, it's essential to explore the apparent omission of Capitalism from their antagonistic narrative, despite the internal purges of the party's leftist elements, which were rooted in power struggles as much as ideology. The explanation is more straightforward than some critiques suggest and requires a closer look at the party's ideology and proposals. Hitler identified "Jewish-Bolshevism" not only as a political threat but also as a capitalist phenomenon, believed to be a manifestation of a Jewish influence. The Nazi's violent campaign against Bolshevism was not just ideological warfare; it was seen as a means to protect nations from what they perceived as the financial domination that could follow in Bolshevism's wake.

“Hitler violently objected to international capitalism even when it was not Jewish, but he assigned the Jews a particularly malevolent role within the global capitalist system; this remained the principal root of his anti- Semitism. In Mein Kampf, as in his earlier rhetoric, Jews were inseparably linked with money and the whole capitalist system as ‘traders’, as ‘middlemen’, who levied an ‘extortionate rate of interest’ for their ‘financial deals’. Jewry, he claimed, aimed at nothing less that the ‘financial domination of the entire economy’.”

— Brendan Simms, Hitler: A Global Biography

Considering the extensive historical data available, it's impractical to distill the intricate interactions between the NSDAP and Capitalism into a single summary. For a thorough understanding, one should refer to well-researched books on the subject. This article will now turn its attention to Dr. Robert Ley, whose role in Nazi Germany has not received as much attention in popular historical narratives. Ley's contributions were significant, and his example suggests that there were indeed anti-Capitalist elements within the NSDAP, an aspect that is frequently overlooked or minimized by many scholars and commentators.

Robert Ley: The Man

Born on February 15, 1890, in the Rhine province of the German Empire, Robert Ley emerged from a life of poverty in a rural setting, where he was one of thirteen children. Confronted with the hardships of the lower class, Ley nonetheless climbed from his modest origins to advance his education, eventually aiming for a doctorate in chemistry. His studies were put on hold when he volunteered to serve in World War I, starting in the artillery and then moving on to work as an aerial artillery observer. His service took a dramatic turn when he was shot down by French forces, resulting in his capture and detention as a prisoner of war until the conflict concluded.

A portrait of Robert Ley

After Germany's defeat in World War I, Ley resumed his academic pursuits, earning a Ph.D. in Chemistry. He later landed a job with the industry giant IG Farbenindustrie. His political outlook began to change in response to the French occupation of the Ruhr, and he found himself aligning with nationalist sentiments. Ley was particularly swayed by Adolf Hitler's rhetoric, which at that time was largely associated with the Beer Hall Putsch. This led him to join the National Socialists in 1925. Within the Nazi party, Ley quickly rose to prominence, fueled by a passionate desire to better the lives of workers. He openly criticized the sacrosanct concept of private property and pushed for more social and economic equality. His staunch advocacy for workers' rights and welfare earned him a powerful and influential status within the party.

“Today the owner can no longer tell us, 'my factory is my private affair.' That was before, that’s over now. The people inside of it depend on his factory for their contentment, and these people belong to us.... This is no longer a private affair, this is a public matter. And he must think and act accordingly and answer for it."

— Robert Ley quoted in Hitler's Revolution by Richard Tedor

As a pivotal member of the National Socialist government, Ley's stature within the party grew, making him an essential figure in the formation of its ideology. His leadership of the German Labour Front (DAF), a central syndicate in the government, stands out among his achievements. In charge of the DAF, Ley played a critical role in the narrative of the Nazi regime. He worked to forge a stronger connection between the workforce and the state, and he was key in persuading many workers to embrace National Socialist principles. Under his guidance, the DAF became a crucial mechanism for promoting the party's goals and expanding its reach into the working-class population.

Ley’s Ideas on Labour

“In April 1933 Hitler closed down the trade unions; he transferred their staff, members, and assets one year later to a monolithic German Labour Front, the DAF. It was the biggest trade union in the world, and one of the most successful. Dr. Robert Ley, the stuttering, thickset Party official who controlled the DAF for the next twelve years, certainly deserves a better appraisal from history. The DAF regularly received 90 percent of the subscriptions due – an unparalleled expression of the thirty million members’ confidence. With this vast wealth the DAF built for them holiday cruise liners, housing, shops, hotels, and convalescent homes; it financed the Volkswagen factory, the Vulkan shipyards, production centers in the food industry, and the Bank of German Labour… Labour leader Ley was to stand by Hitler beyond the end.”

— David Irving, The War Path

During the era of National Socialist governance, Robert Ley became a prominent proponent for the labor force. With the ban on trade unions and strikes, Ley was instrumental in the creation of the DAF. Drawing inspiration from the Italian Fascist organization Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro, the DAF was designed to bridge the gaps between social strata and to instill National Socialist principles thoroughly within both the workforce and the employer base. Ley steered the DAF’s efforts to reorient the nation's workforce educationally, aligning them with what Hitler deemed "genuine socialism," and fostering a collective national unity. His leadership in this transformative process was critical and was considered one of the most significant tasks within the party. Ultimately, Ley's execution of his duties was effective, as history records his success in fulfilling this ambitious goal.

The German Labour Front flag

To appreciate the nuances of Robert Ley's ideological position and the inferences he made, one must examine his reasoning and core beliefs. Ley was an ardent advocate of Hitler's ideologies and consistently echoed his support through his public addresses, writings, and overall ideological outlook. Nonetheless, it's essential to acknowledge that Ley had his unique interpretations and angles on these ideas. While Hitler appeared to adopt a cautious stance towards industrialists, this should not be misconstrued as a complete absence of anti-capitalist undertones in Nazi thought.

The concept of "Judeo-Bolshevism" was indeed a prevalent motif in NSDAP rhetoric, yet this did not equate to an outright rejection of Capitalism. Intriguingly, discussions within the party on the topic of Bolshevism often hinted that Capitalism was perceived as an ally of Marxism, suggesting a complex relationship. From the National Socialist viewpoint, following World War I, Bolshevism was seen as a mechanism exploited by Capitalist forces to debilitate sovereign states. Ley's ideological convictions provide a clearer stance on this issue, as he directly attributed to Capitalism an inherent Jewish essence. In Ley's analysis, not just Bolshevists but also capitalists were regarded as part of a divisive scheme designed to dominate and fracture the nation. His perspective accentuated the idea that Capitalism, as much as Bolshevism, was complicit in undermining the unity and strength of the country.

"Let us remember, National Socialists, the struggle in the interior against the plutocratic forces. In the moment that we understood what the power of money meant, the fight was already over. The plutocrat is not smart, and when he's exposed, neither he, nor his straw men, nor his satellites are something to fear. Soon the parties that were purely capitalists and the individuals and organizations that they financed such as the Marxist and centrist party, came to an end. From the very moment that you can show the people their tricky tactics, plutocracy loses all its power.”

— Robert Ley, Socialism: The Envy of Our Enemies

Ley was vocal in his opinion that those in Germany who exhibited anti-Semitic views while also supporting Capitalism were not fully cognizant of the contradictions in their stance, branding them as uninformed reactionaries. He argued that such individuals overlook their adherence to what he dubbed the "golden calf" of Capitalism. For Ley, Capitalism epitomized a Jewish-influenced ideology that thrived on exploiting and dividing the populace, thereby sapping the collective vigor of the German people. He was critical of a life dedicated to the pursuit of wages and succumbing to materialism and hedonistic comforts. In Ley's perspective, it was imperative for industrialists to conform to the National Socialist vision for the nation. He suggested that those who resisted aligning with the party's agenda would inevitably face repercussions, regardless of their individual preferences or inclinations.

“I always say that workers and managers belong together, and we will not leave you alone whether you want us to or not, whether you like it or not. If the manager says: ‘It is ridiculous that I always have to participate in employee meetings, I won’t do it,’ we reply ‘You must do it! Ten thousand workers are marching. The best German blood! It should be an honor for you to march at their head. If you do not want to do that, we will have to put you back in the ranks where the man behind you can tread on your heels until you do it properly. We will teach you, believe me. We will not give up.’”

— Robert Ley, Fate — I Believe!

Ley did not mince words when it came to Capitalism, candidly expressing the party's stance on private property, which he considered to be communal to a certain degree. He underscored the necessity of worker welfare within this context. Furthermore, Ley was of the opinion that workers ought to have a sense of participation in a cause larger than their individual lives. This is where the ideology of National Socialism gains its significance. It is an ideology that is anchored in the concept of collective duty—aimed at enhancing the overall welfare of society and cultivating national cohesiveness through a naturally integrated national community. In his work, Hitler's Revolution, Richard Tedor delves into the specific nature of the socialism endorsed by Hitler and his adherents, providing insight into the philosophical underpinnings and practical implications of their version of socialism.

“Hitler saw nationalism as a patriotic motive to place the good of one’s country before personal ambition. Socialism was a political, social and economic system that demanded the same subordination of self-interest for the benefit of the community. As Hitler said in 1927, ‘Socialism and nationalism are the great fighters for one’s own kind, are the hardest fighters in the struggle for survival on this earth. Therefore they are no longer battle cries against one another.’ Die SA summarized, ‘Marxism makes the distinction of haves and have-nots. It demands the destruction of the former in order to bring all property into possession of the public. National Socialism places the concept of the national community in the foreground.... The collective welfare of a people is not achieved through superficially equal distribution of all possessions, but by accepting the principle that before the interests of the individual stand those of the nation.’“

— Richard Tedor, Hitler’s Revolution

These ideological tenets deeply affected Ley, molding his political convictions and life ethos. He elevated the notion of socialism, persistently championing measures that confronted the agendas of industrial magnates and the party's conservative elements. Consequently, he sometimes found himself branded as a Marxist. Regardless of the internal strife that riddled the NSDAP over the years, including the targeting of individuals such as the Strasser brothers, Ley adeptly maneuvered through these internal disputes. He stood out as a tenacious and long-standing member of the party.

"One of the most important new social organizations was the German Labor Front (DAF). Under its director, Robert Ley, the DAF quickly swelled to more than 6 million members and by 1938 maintained a larger budget than the Nazi Party. The Law for the Ordering of German Labor of January 1934 created a structure of leaders and their “retinues” (workers) in each factory, with Courts of Social Honor for both. Though under strict hierarchical control, the DAF did not ignore worker interests and often acted to improve conditions. Unlike the situation in Fascist Italy, shop stewards did operate under the DAF, though the first elections to “councils of trust” in factories produced so few positive votes they were never tried again... Ley hoped to build the Labor Front into a major autonomous force, even conceiving the ambition of having it replace the party as the basis of National Socialism, though such aims were soon quashed."

— Stanley G. Payne, A History of Fascism

Unlike some fascist counterparts, Ley's public discourse and key messages were notably in sync with Mussolini's during the existence of the Italian Social Republic before the conflict. They both highlighted the conflict between the working class and affluent nations, cast doubt on the inviolability of private property, called for substantial governmental control, and voiced vehement objections to Capitalism and the wealthy elite. While differences in principles and incentives might account for their distinct courses of action, it illustrates the common perception of Mussolini as a staunch anti-capitalist, in contrast with the belief that the NSDAP adopted a more accommodating approach to Capitalism. Nevertheless, the presence of figures like Robert Ley, who effectively rallied workers and party affiliates to put national welfare above private interests, questions the assumption that the German National Socialist regime uniformly took a soft stance on Capitalism. This hints at a potentially overlooked aspect of the NSDAP's ideology and policies that may not be widely recognized.

Ley giving a speech to factory workers

Robert Ley harbored deep respect for Mussolini and championed the idea of worker exchanges between Italy and Germany. He was convinced that both countries faced a mutual foe in Capitalism and its strategic manipulation of Marxism. Ley considered it crucial to build an alliance and encourage cooperation between these worker-centric nations. He envisioned a potential camaraderie and reciprocal backing in their collective fight against the perceived malevolence of Capitalist forces. Ley's esteem for Mussolini and his initiatives to bolster collaboration between Italy and Germany were indicative of his conviction in the necessity of solidarity in confronting a shared challenge.

“I shall talk of a new innovation: the trains of exchange, the fruits of our agreement with Italy; the first proved how excellent this idea was. At the beginning of October, 425 Italian workers, members of Dopolavoro, came to Munich, Nuremberg & Berlin. Our biggest happiness was that of seeing the happiness of Italians, our guests and the enthusiasm with which they adopted the points of the program we offered. A little time later, a large express train, with first and second-class cars, carried 425 German workers from Berlin to Rome and Florence going through Brenner. Media from the entire world gave us the details of the trip of our comrades from the reception of the Duce until the presentation of the Florence Opera. Two organizations with the same end – Strength through Joy and Dopolavoro- joined the same Labour to consolidate the axis Berlin-Rome thanks to the practical work of the approach of these two countries…”

— Robert Ley, A Folk Conquering Joy, Fourth Anniversary of Strength Through Joy

“The Führer found in Italy’s Duce a revolutionary of like good sense and reasonableness. Only the friendship of these two men, their clarity and determination, gave Europe security through the Axis. Now it was necessary to see which worldview had the greater power and strength… Jewish internationalism also had to be destroyed internationally. Fanatic National Socialism and pacifistic internationalism are like fire and water and can never exist alongside each other. They are like fire and water, and sooner or later there must be a battle between these two worlds. This battle would show whether Jewish democracy and Jewish internationalism would win and were the stronger, or whether National Socialism and Fascism, tied to nature and obedient to nature’s laws, would be victorious. There was only an either/or. If the National Socialist and Fascist Axis were to triumph, the Jewish democratic-parliamentarian system would have to be destroyed…

This whole international institution, the International Labor Office in Geneva, was nothing but a way for the capitalists of the world to regulate their world capitalist goals. With the help of international slogans and international agreements, countries like Germany and Italy should limit their production, thereby reducing economic competition.”

— Robert Ley, International Ethnic Mush or United National States of Europe?

Robert Ley in Italy with Labour Leader Tulio Cianetti

Robert Ley worked in tandem with Tulio Cianetti to orchestrate a program for the interchange of laborers between Germany and Italy. Cianetti, who occupied a significant role within the DAF, was held in high esteem, a fact underscored by having a recreational facility at Volkswagen industries named "Cianetti Hall" in his honor. This accolade stemmed from Cianetti's vigorous efforts and his ideological sync with Ugo Spirito's stance, which was characterized by a rejection of both Capitalism and Communism as principal adversaries of the Fascist agenda. Furthermore, Cianetti was known to hold approving views of German racial doctrines. The ideological kinship between Ley and Cianetti was fundamental in fortifying the ties between the German and Italian workers' movements. Their cooperative efforts and aligned ideologies contributed to laying the groundwork for the eventual establishment of the Pact of Steel, a significant military and political alliance between Germany and Italy that would materialize in the near future.

“The exchange of workers that Italy and Germany have started acquires larger proportions each time bigger proportions. In this way, beauty, effort, and the Labour of each one of our two folks will be magnificently patent for the other. Nations will get to meet each other and understand themselves in the best way of the word”

— Robert Ley, Rome capital speech 1938

Robert Ley with Benito Mussolini in Rome

The praise of Robert Ley's appreciation for workers prompts a significant question about his view of the laborer and the nature of work itself. To elucidate his stance, Ley articulated his thoughts across various platforms, including speeches and written pieces, most notably in his 1939 piece entitled To Each German, Their Position! In this pivotal publication, he unambiguously articulated his perception of the worker and the essence of labor, providing a clear exposition that left little to interpretation or guesswork.

“Work is Structure, knowledge of the regularity that rules the world. Working is discipline, this same formula discovered by National Socialism that convenes to know: vision of regularity, and the declaration that discretion cannot be given. Everything is sacrifice and an object of eternal regularity…

We consider Labour the genuine expression of our race. For every work that I start, the first that I must do, inside myself, is organize and create. I shall always consider my Labour as a start and an end. Thus, steadily, I shall arrive at the accomplishment of a system, in such a way, in which the product of the Labour, shall be the expression of self-discipline…

Working is Art; it is an aspiration for harmony. Every worker is an artist in its own way. A glass blower in Thuringia is an artist of great prestige; a watch mechanic is an artist. Examples like these can multiply at our pleasure. We see, then, that work in every man can be reduced to a common denominator. Culture consists, precisely, in the sum of Labour across time…

Man cannot be valued by their type of Labour, but through the quality of his performance in the sphere and place in which he is located. It’s indifferent if the worker is a manual worker or a teacher: both shall be valued the same; because one couldn’t exist without the other, and, to each their part, they cooperate in what we call Culture. Above all, we must take into account the extent to which, Labour as a whole, is useful for the community of the entire country…

What is, then, the end goal that Labour pursuits? What leads human effort into building, producing, inventing, and working in the soil of their nation? This cannot be explained by the needs of the stomach. It is, on the contrary, of the spiritual aspiration of the eternal, carried inside the heart of every men. Every men desires, and proposes that the work that lasts, the piece that he creates, survive –to him and time- until the deepest dimensions of the future.

Men has to find on itself the capacity for a vocation, for the call that he gets. This knowledge must be infiltrated in our people… That’s why we must attempt, through every way, of destroying unclassified Labour. We must elaborate the capacities of our people. We must end the empty spaces. Specialized Labour is our true Capital that doesn’t depend on foreign forces nor foreign exchange… A Capital that we have the obligation to take care of and spread. This is the true Capital of folk with little natural resources.

Thus, we shall put every man in their adequate position. We see here, a mental attitude that breaks entirely the habits and thesis of the past. When someone says that under this criteria we take away the liberty of men, I respond: we, in reality, make men internally more free. Men have to overcome the egoist impulse of individuality to substitute it for the thoughts of loyalty, camaraderie and community...”

— Robert Ley, To Each German, Their Position!

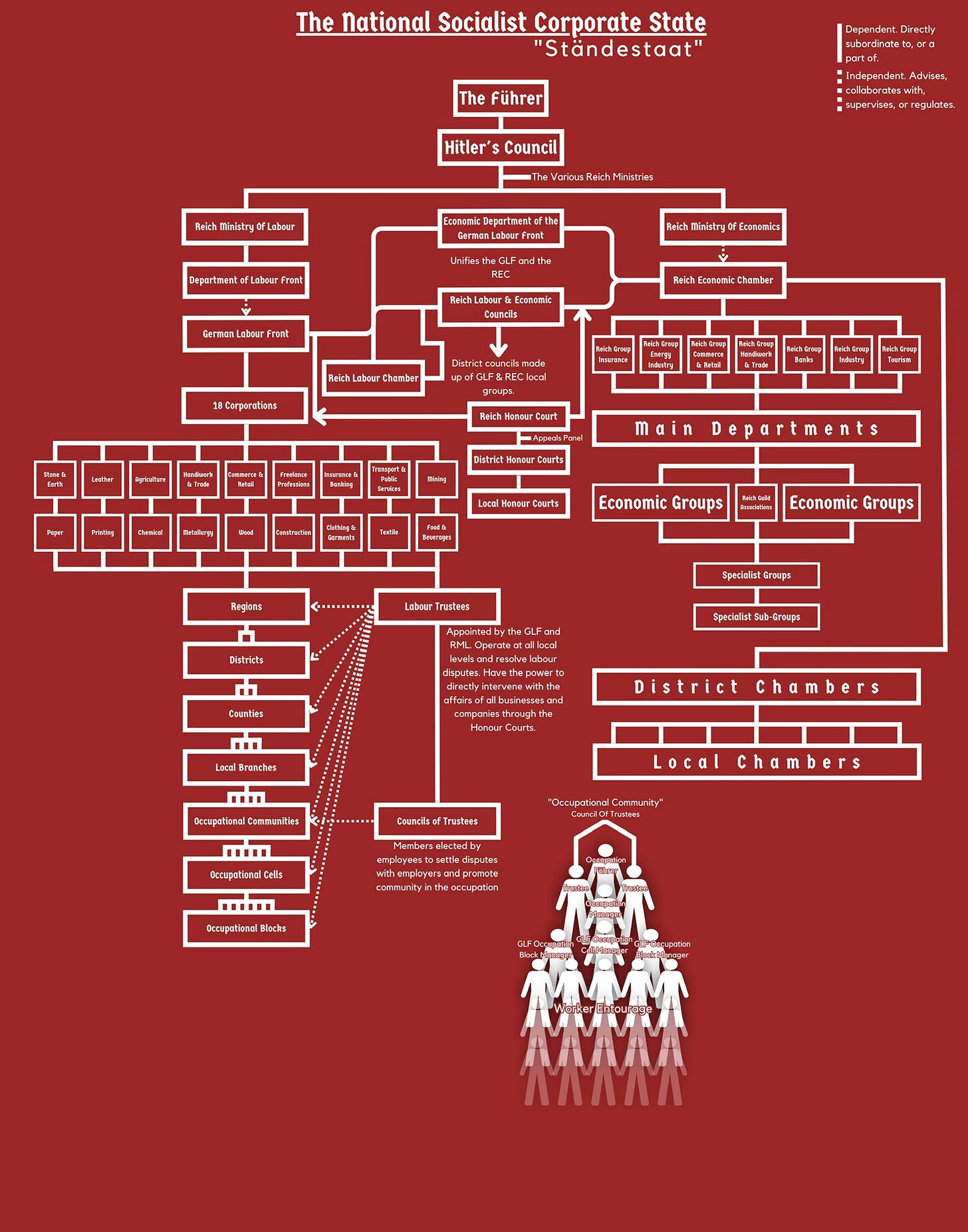

The Nazi Corporate State and the organization of the DAF

Ley's rise within the NSDAP was marked by his dedication to developing policies and a deeper understanding of labor. His theories resonated with the German workforce, but it's critical to examine how these theories were put into practice. Looking at Ley's life work—what he saw as his own form of artistry—we encounter the DAF, an organization central to Ley's professional journey. Created by Hitler to serve as an instrument for the ideological reeducation of the workforce, the German Labor Front sought to instill a communal spirit among German laborers. Hitler viewed the reeducation of the populace as essential to the triumph of the National Socialist revolution. In a 1933 address, he discussed the importance of revolutions in history and stressed the need for success in this transformative process.

Robert Ley quickly climbed to a key role within the German Labor Front, steering the direction of this nascent organization. With Ley at the forefront, the DAF established a framework that organized different productive sectors and aimed to resolve conflicts between labor and management. The party's conceptualization of production led to a change in language, moving away from the traditional designation of "employer and employee" to the nomenclature of "leader and follower." In the context of German legislation, the "leader and follower" dynamic in the workplace was characterized as follows:

“The leader of the facility makes decisions for the followers in all matters of production in so far as they fall under the law’s regulation. He is responsible for the welfare of the followers. They are to be dutiful to him, in accordance with the mutual trust expected in a cooperative working environment.”

— Robert Ley quoted in Hitler’s Revolution by Richard Tedor

A key function of the DAF was to adeptly manage and settle disputes that emerged between laborers and business executives. Mirroring the approach of the Italian Fascist Corporative system, the state acted as an intermediary between the two groups, aiming to achieve a resolution that would reestablish equilibrium. The investigative work of Richard Tedor has unearthed numerous documents that offer a deeper understanding of the methods utilized by the DAF to accomplish this essential role.

“The record of court proceedings for 1939 demonstrates that the labor law primarily safeguarded the well-being of employees rather than their overseers. During that year, the courts conducted 14 hearings against workers and 153 against plant managers, assistant managers and supervisors. In seven cases, the directors lost their jobs”.

— Richard Tedor, Hitler’s Revolution

The DAF was not solely focused on resolving conflicts but also on fostering work environments that were both healthful and visually appealing, to avoid a monotonous and uninspiring atmosphere. To this end, the DAF instituted a section called the Beauty of Labor (Schönheit der Arbeit), dedicated to maintaining high standards of cleanliness, providing appropriate tools and machinery, and ensuring the safety of workplaces. In instances where there was a significant breach of these standards, the German regime would call upon the Gestapo, the secret police, to intervene. This measure was taken by the DAF to correct attitudes and practices that contributed to social inequalities. The involvement of the Gestapo was a strategy to ensure adherence to the DAF's vision of a well-ordered and fair working climate.

As Hitler would describe:

“The police should not be on people’s backs everywhere. Otherwise, life for people in the homeland will become just like living in prison. The job of the police is to spot asocial elements and ruthlessly stamp them out.”

— Adolf Hitler quoted in Hitler’s Revolution by Richard Tedor

Under the guidance of Robert Ley, the DAF launched one of its most far-reaching programs: the recreational division known as Strength Through Joy (KDF). Ley personally proclaimed the start of this initiative, underscoring its importance and aims.

“We should not just ask what the person does on the job, but we also have the responsibility to be concerned about what the person does when off work. We have to be aware that boredom does not rejuvenate someone, but amusement in varied forms does. To organize this entertainment, this relaxation, will become our most important task”.

— Robert Ley quoted in Hitler’s Revolution by Richard Tedor

Within the framework of the KDF initiative, the DAF vigorously endorsed and provided avenues for German workers to travel abroad. The program also backed an array of cultural pursuits by offering financial support and additional resources. The principal goal was to afford workers the chance to unwind, appreciate the beauty of their homeland, and venture into other countries, all within a serene and wholesome setting, without neglecting their professional responsibilities.

“Few Germans could afford to travel prior to Hitler’s chancellorship. In 1933, just 18 percent of employed persons did so. All were people with above-average salaries. The KdF began sponsoring low-cost excursions the following year, partly subsidized by the DAF, that were affordable for lower income families. Package deals covered the cost of transportation, lodging, meals and tours. Options included outings to swimming or mountain resorts, health retreats, popular attractions in cities and provinces, hiking and camping trips. In 1934, 2,120,751 people took short vacation tours. The number grew annually, with 7,080,934 participating in 1938. KdF “Wanderings"-- backpacking excursions in scenic areas— drew 60,000 the first year. In 1938 there were 1,223,362 Germans on the trails. The influx of visitors boosted commerce in economically depressed resort towns…

In its endeavors to fully integrate labor into German society, the KdF introduced cultural activities as well. Its 70 music schools offered basic instruction in playing musical instruments for members of working class families. The KdF arranged theater productions and classical concerts for labor throughout the country. The 1938 Bayreuth Festspiel, the summer season of Richard Wagner operas, gave performances of Tristan und Isolde and Parsifal for laborers and their families. The KdF also established traveling theaters and concert tours to visit rural towns in Germany where cultural events seldom took place.”

— Richard Tedor, Hitler’s Revolution

Under National Socialism, the DAF's effectiveness ensured the activation of the working class, facilitating their engagement in activities that were once beyond reach. These initiatives were not just about material satisfaction; they were designed to fortify the connection between laborers and the nation. Robert Ley had broader ambitions than these initial measures, as he consistently pushed for tougher actions against industrial giants to benefit the working populace.

It's essential to grasp that within the National Socialist framework, the presence of private property did not negate its opposition to capitalism and its goal to uproot the capitalist framework within Germany. This distinction becomes clear when acknowledging that, in fascist ideology, conceptual doctrines are deemed more critical than material circumstances. By severing the concept of capitalism from the notion of private ownership, one can infuse and shape it with their own narrative and worldview. This approach steps into the philosophical discourse between materialism and idealism, but confronting this point is key to debunking the widespread misbelief that Hitler's regime, through its privatization initiatives, was inherently capitalist, which it was not.

As Mussolini articulated, Italian Fascism's state intervention in the economy could take two forms: either through direct ownership and operation or control of property. Whichever method was employed, the end remained constant—the embedding of national doctrines into the economic practices of the country. Hence, this economic model is fundamentally based on corporatist philosophy. Within National Socialism, the Fichtean idea of socialism, as depicted in the concept of a closed commercial state, underpinned their version of a nationally focused, duty-centered socialism. In Nazi Germany, the state prioritized national interests in dictating and guiding property use, creating a plethora of bodies to regulate and supervise, circumventing the need for outright nationalization.

“Moreover, Nazi decrees of 1937 compelled further cartelization to streamline the chain of command and prepare for war, which had been the goal of the Four-Year Plan of 1936. The results of this massive interventionist policy were ‘complete consolidation of the entire economy, complete elimination of personal initiative and freedom of choice.’ Even if a semblance of private ownership of business remained before the outbreak of World War II, with war raging on two fronts the National Socialists took the final step when they created the Amt für Zentrale Planung (Office for Central Planning) in 1942 which removed any remnants of private initiative."

— Matthew Ryan Lange, Anti-Semitic Anti-Capitalism In German Culture

“Even heavy industry, that had favored some degree of autarky and state aid in the early 1930s, found that the extent of state control exercised after 1936, and the rise of a state-owned industrial sector, threatened their interests too. The strains that such a relationship produced have already been demonstrated for the car industry, the aircraft industry and the iron and steel industry; but much more research is needed to arrive at a satisfactory historical judgement of the relationship between Nazism and German business. What is already clear is that the Third Reich was not simply a businessman's regime underpinning an authoritarian capitalism but, on the contrary, that it set about reducing the autonomy of the economic élite and subordinating it to the interests of the Nazi state…

As the state extended its role in supervising or regulating all the main economic variables, they developed a more coherent economic system. German economists christened the system 'die gelenkte Wirtschaft', the managed economy. Under such a system businessmen were regarded as economic functionaries serving the interests of the nation rather than as independent and enterprising creators of wealth. The concept of the 'managed economy’ suited the regime's ideological ambitions, but stifled enterprise.”

— Richard Overy, The Nazi Economic Recovery

“Both public works and rearmament required massive deficit financing, in effect the printing of money to pay workers and stimulate demand. Although fundamentally ‘socialist’ in outlook and politics when it came to the economy, however, Hitler did not nationalize industry. In fact, there were large-scale privatizations during the first five years or so of his regime, not for ideological reasons, but to raise cash quickly by flogging off distressed enterprises. What Hitler did very effectively was to nationalize German industrialists, by making them instruments of his political will. Control, not ownership, was the key. The major German economic institutions, especially industry, business and the banks, were completely sidelined from decision-making. Unlike the Reichswehr, they were not let into any secrets about Lebensraum, at least at the beginning. They were simply told what to do, and if they jibbed were threatened with imprisonment, expropriation or irrelevance.”

— Brendan Simms, Hitler: A Global Biography

Robert Ley was unwavering in his beliefs, often pushing for more extreme measures than the relatively moderate control over industrialists typical of German policy at the time. He did not hesitate to employ agencies like the Gestapo, which were originally established for such enforcement. Throughout the tenure of the government, Ley was vocal and persistent in advocating for his views, irrespective of what other members of the NSDAP thought. He stood firm on his stance and advocated for initiatives that, although initially met with opposition, eventually became more widely accepted. Importantly, Ley's loyalty to Hitler as the Führer did not prevent him from expressing his disagreements. This highlights his capacity for independent thought and his readiness to stand by his convictions, showcasing a deep-rooted dedication to his principles.

“The National Socialist government required that all working people be guaranteed a minimum of six days off after six months' tenure with a company. As seniority increased, the employee was to earn twelve paid vacation days per annum. The state extended the same benefits to Germany’s roughly half a million Heimarbeiter, people holding small contracts with industry who manufactured components at home. Contracting corporations financed their holidays as well. Ley fought the labor ministry for years before finally extending the work force has paid annual leave to four weeks.”

— Richard Tedor, Hitler’s Revolution

“Another proposal introduced by the DAF leader was that when workers have to stay home due to illness, the employer must continue to pay 70 percent of their salary. Employees absent from work to care for family members would receive the same compensation. Once again, Ley advocated tapping into the profits of industry to elevate the standard of living for labor. Ley and Conti eventually compromised, signing a national healthcare agreement at Bad Saarow in January 1941. It authorized the founding of free local clinics, annual physicals for all citizens, and state financed coverage for medical treatment of sick and injured persons. This negated the need for people to purchase medical insurance. To offset expenditures, the plan called for far-reaching ‘preventative medicine’ measures. The DAF allotted funds to build more health spas, resorts, and other recreational facilities to serve as local weekend retreats for workers and their families. This was to improve public health through rest and relaxation.”

— Richard Tedor, Hitler’s Revolution

“During World War II, German women filled many positions in the armaments industry, on a lower wage scale, as more males entered military service. In April 1944, Ley, who had campaigned for equal pay for women for years, confronted Hitler on the subject. The Führer explained that Germany’s planned post-war social structure envisions women as the hub of the family, adding that this does not imply a negative opinion of their intelligence or occupational capability. Ley retorted that successful German women have a modern cognizance of their role in society and consider Hitler’s ideas archaic. In the course of the meeting, Ley tenaciously defended his stand against an avalanche of counter-arguments his leader presented. The Führer finally relented by offering a compromise, that women should receive less base pay, but be eligible for incentive awards and bonuses to compensate for the disparity. In general, Hitler’s personal view had little influence on developments: In the winter semester of 1943/44 for example, 49.5 percent of students enrolled in German universities were women”

— Richard Tedor, Hitler’s Revolution

Robert Ley's standing among the working class and his unwavering adherence to National Socialist principles helped solidify his position within the party, allowing him to weather the storms of purges and internal power struggles. He maintained his dedication to the cause until the regime's final days. Ley's initiatives and his perceived advocacy for the common good earned him a great deal of respect from the public but also animosity from industrialists. His determined drive to develop the German Labor Front into a pervasive institution across Germany drew ire from certain NSDAP figures, like Goebbels, yet Ley's tenacity ultimately won over Hitler's endorsement. This support enabled him to further social welfare programs for workers, taking cues from the Italian Dopolavoro, a model Ley openly cited as an influence on the German Labor Front's approach. The advent of World War II, however, signified a pivotal shift and signaled the beginning of the end for the National Socialist government. In spite of Ley's contributions, the war's unfolding events precipitated the progressive deterioration and eventual collapse of the regime.

Endkrieg

Until the regime's final moments, Robert Ley's allegiance never faltered; he resolutely backed and championed every measure designed to secure the endurance of the German populace throughout the wartime period. Yet, even with the primary focus on aiding the war effort, Ley persisted in his call for systemic reforms to achieve his conception of a utopian society. Occasionally resorting to drastic actions, his suggestions encountered resistance from fellow NSDAP members who harbored contrasting opinions and agendas.

For example, in David Irving’s Hitler’s War the following situation is exposed:

“Reichsmarschall Göring presented Korten to Hitler on August 20; on the same day Hitler discussed with Dr. Ley and leading architects how to provide for the bombed-out families. Ley offered to build 350,000 homes a year, but Speer interrupted: ‘I will not provide the materials, because I cannot.’ Hitler would not hear of that. ‘I need a million new homes,’ he said, ‘and fast.’”

— David Irving, Hitler’s War

Robert Ley consistently prioritized the well-being and perseverance of the German commoner, a commitment that sometimes put him at odds with other high-ranking NSDAP figures. As the regime neared its conclusion, the emphasis shifted wholly to the war effort and uniting Germans against their adversaries. In this period, Ley was known for his stirring orations and influential writings, which sought to rally support for the national cause.

Yet, his 1944 publication The Pestilential Miasma of The World stands out as one of his most provocative and incendiary creations. Within its pages, Ley aimed vitriolic accusations at the Jewish people, blaming them for initiating the conflict and for allegedly pulling the strings behind the scenes to have others wage war in their place. He further attacked Jewish people by claiming they exerted undue control over both capitalist and Bolshevik spheres. Notorious for its offensive content and crude language, this book is a stark representation of Ley's radical ideology in those chaotic times.

“This war is a battle between worldviews, and the side that has the strongest faith will be victorious. Only he who is convinced of the justice of his cause, and who in fact has justice on his side, who acts reasonably and correctly, who recognizes and follows the laws of nature, can have the strongest faith…

Capitalism was born from fatalism. Calvin, one of the most important Jewish hirelings, says: ‘He who is poor must remain poor, and he who is rich must make more money. It is a sin to teach otherwise.’ The Jew says: ‘All is determined in advance’ (Pinke abot 111)…

This becomes evident only when others have power over the Jew and he can no longer escape his fate. As long as he thinks he can conceal things with some success behind the Jewish mask, he will do so. There is no stronger bond than that which joins criminals. One Jew protects the other, at least to the outside world, regardless of the distance between them, or whatever social differences may exist between them. The Jew in America protects the Jew in Poland, Moscow, or Berlin, the rich Jew protects the poor Jew, and the poor Jew protects the rich Jew…

We see this in the Congress of Vienna, in the Treaty of Versailles, in the Geneva League of Nations, as well as in international labor unions or the Bolshevist central in Moscow. It is always the same. Together with capitalism, money and usury, these organizations serve the purpose of uniting Judah across all peoples and national boundaries, and concealing their misdeeds…

The Jewish mentality and the Jewish spirit are the worldview of fatalism, of ghosts and spirits, of terror, of anxiety and fear, of the money bag and capitalism, of the denial of life and surrender, of begging and pity, of those who lack will, of the cowards — in a word, the bourgeois-Marxist world in which we who are older grew up. That is why it is so hard to free ourselves from it…

He who accepts the Jew’s money and earns his money through those exploitative methods will be ruined. He who holds work in contempt, who sees his German racial comrades as those to be exploited, who sees labor as a product like herring and cotton, is an enemy of the people, a traitor, and deserves no pity. The counterpart of this Jewish-capitalistic thinking is the twin of capitalism, the Jewish changeling and Jewish bastard, Bolshevism. Each resembles the other. I do not believe that they have many supporters in Germany…

There is thus in this struggle against Judah only a clear either/or. Any half measure leads to one’s own destruction. Judah and its world must die if humanity wants to live; there is no other choice than to fight a pitiless battle against the Jews in every form, and not to give up until the last Jewish thinking has been destroyed everywhere.

When the English and Americans finally realize that they are fighting in reality for the freedom of the Jews, they will become reluctant, and will be critical of the Jews; they will discover the Jews. That is enough to make an anti-Semite of any Aryan. That is what the ‘Jewish Chronicle’ means when it complains: ‘Anti-Semitism has become a universal problem.’ That is true! The Jew is being discovered in the entire world as a result of this war, he loses his concealment, and is thus already defeated. Anti-Semitism is ‘Hitler’s secret weapon,’ which will lead us Germans to inevitable victory.”

— Robert Ley, The Pestilential Miasma of The World

“The Jew as Oppressor of Humanity”

During this critical phase, Robert Ley was also known for his influential oratory. His speeches from the time underscored the united front between the Fascist regime of Italy and the National Socialist regime of Germany as they faced their mutual foes. Ley stressed the significance of their partnership, drawing attention to the solidarity and collaborative efforts of the two ideologies in their collective battle against their opponents.

“This war does not only involve Germany, this war concerns precisely every European nation. It gets to Fascist Italy, that is on our side, with their blood, and the great Italian Duce is the granter of this. That Fascism and Italy trust Germany, they trust in this struggle against Judah... It is a struggle of workers of all nations, against the outlaws of Capitalism: Judah.”

— Robert Ley, 1945 last speech

In some respects, the era of World War II can be seen as a distinctive moment when something akin to a Fascist Internationale was in effect, at least in a practical sense. This context contributes to the perception of the war as the ultimate downfall of Fascist ideologies, marking a decisive conflict for their existence. From Italy's perspective, the war was framed as a confrontation between proletarian nations and a blend of capitalist plutocracy and Bolshevism. Meanwhile, Germany perceived the conflict as a crusade against what it labeled the Jewish influences behind capitalism and Bolshevism. There was a clear intersection in the ideologies and goals that each nation espoused. As the conflict intensified, the conditions became exceedingly harsh and relentless. The language Robert Ley used as the war neared its end mirrored the severe impact it had on the psyche of the party's members, with some of his rhetoric even devolving into outright advocacy for genocide. One of his most jarring pronouncements about the war's potential end might be summarized as follows:

“For whosoever undergoes the struggle against Judah initiates a struggle for life or death. There won’t be another Peace of Versailles, if we Germans were to lose this war, then the German people would be exterminated to the last man! The Jew will not receive any warmth or mercy, in this struggle for existence and extinction.”

— Robert Ley, last speech 1945

The collapse of Fascism in Europe signaled the impending end for Robert Ley, despite his fervent support of the war effort. Captured by American forces in 1945, Ley allegedly took his own life before he could be tried at the Nuremberg Trials. His brain was later used for scientific study, and his historical reputation has been clouded by defamation and intentional exclusion from historical narratives. Posthumously, Ley has faced various accusations, including corruption, promiscuity, and habitual intoxication, as part of an effort to tarnish his memory. Nonetheless, such claims frequently stem from dubious sources and poor scholarship, which are all too common in historical works about World War II. For example, the often-repeated claim that Ley suffered a brain injury during World War I, causing a speech impediment, lacks solid proof. The biography Robert Ley: Hitler's Labor Leader leans heavily on the assertions of American psychiatrist Dr. Douglas Kelley, who posited that Ley's alleged brain damage contributed to erratic behavior and alcohol dependency. Yet, later analyses of Ley's brain showed no signs of damage, countering the narrative of neurological impairment and alcoholism.

Throughout the war, the Allies, mirroring Goebbels' tactics, employed pejorative nicknames for Nazi leaders, such as "limping dwarf" for Goebbels and "Reich drunk leader" for Ley. These derogatory monikers have unfortunately endured, further tarnishing Ley's image. Despite this, Ley was a compelling and effective orator, matching the prowess of Goebbels and Hitler. From his early days in the party in 1924 until the end, he was a tireless advocate for National Socialism, the German Labor Front, and various political endeavors. Contrary to the portrayals in some literature, Ley's personal life and character are not thoroughly examined, and many details about him remain obscure. The author of the mentioned biography often cites second-hand accounts and speculation. Sensationalized stories, such as Ley's supposed exhibition of a nude painting of his wife or publicly disrobing her, overshadow a more balanced assessment of his life.

Ley's leadership of the world's largest labor organization and his contributions to social welfare measures, such as improved wages, shorter work hours, and vacation policies, should not be undervalued. Before the war, American experts even looked to Ley's programs as a model, acknowledging the shortcomings of Franklin D. Roosevelt's "New Deal." For a deeper and more nuanced view of Ley and his life, his daughter Renate Wald's memoir Mein Vater Robert Ley or Karl Schröder's work Aufstieg und Fall des Robert Ley, would be the most informative. Robert Ley's story is emblematic of the complexity of historical figures within the NSDAP, often subject to vilification and exclusion from scholarly discourse. Addressing Hitler's anti-capitalist stance is as crucial as discussing his anti-Semitism, as historian Brendan Simms indicates. Figures like Ley highlight the hesitancy among historians to delve into the roots of German anti-Semitism, which could prompt challenging questions about capitalism and modern society. Ley's staunch dedication to the labor cause and his role as a labor representative in a fascist state, despite his modest beginnings, are aspects of his life that merit acknowledgment.