Historical and Demographic Background

In World War One, the Romanians emerged as significant beneficiaries in terms of territorial expansion and population growth. Their nationalist aspirations were largely fulfilled as they witnessed a substantial increase in both landmass and population. However, this expansion brought about a more diverse and heterogeneous society, as various minority groups were incorporated into the newly acquired territories. Notably, the Jewish population in Romania tripled, reaching a total of 750,000 individuals, constituting around 4 percent of the population. Additionally, Romania gained control over Transylvania, a region that housed 2.8 million Romanians, but also 1.6 million Hungarians and a quarter million Germans. Consequently, the country's ethnic composition became more varied, with only 70% being Romanian, and 75% of ethnic Romanians residing in rural areas, while almost 70 percent of Jews lived in urban towns.

These demographic changes were accompanied by new geopolitical realities. Romania, a relatively small and underdeveloped nation, found itself sharing a border with the rapidly industrializing and ideologically hostile Soviet Union to the North. To the West, Hungary eagerly sought to reclaim Transylvania and incorporate the Hungarian population residing there.

Furthermore, economic concerns demanded attention. Romania remained predominantly agrarian and rural, lacking a substantial middle class apart from certain urban centers. The number of working-class proletarians paled in comparison to the vast number of peasants who relied on agriculture. In 1930, only approximately 7% of Romanians were involved in industrial activities. Despite its size, Romanian industrialization was largely driven by foreign investment, with three-quarters of all industrial capital originating from abroad. Foreign investment also played a significant role in the Romanian banking industry, accounting for one-third of its capital.

Ethnic considerations further complicated economic affairs, particularly with regard to the Romanian middle class, which was largely dominated by Jewish individuals. According to a French source at the time, 70% of journalists, 80% of textile industry engineers, and 50% of army medical corps doctors in Romania were Jewish. The expansion of Romanian borders in the early 1930s led to a situation where 43% of university students had foreign origins, and approximately 14% of them were Jewish, despite Jews constituting only 4% of the population at that time. Thus, Jews were overrepresented in universities, being three and a half times more likely to attend compared to their population share. Notably, almost half of the graduates in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Cluj were Jewish. This occurred despite the Romanian government's efforts to promote Romanization by sending Romanian students to university in order to foster a more ethnically Romanian middle class.

Prior to the 1800s, there were relatively few Jews in traditional Romanian territory, with their total number estimated around 10,000. However, starting in the late 1870s, Jewish immigrants from the western part of the Russian Empire, known as the Pale of Settlement, began regularly migrating to Romania due to economic hardships resulting from conflicts between the Ottomans and Russians. Additionally, a new wave of Jewish immigrants arrived during World War I as a consequence of the Russian Civil War.

The lack of assimilation further complicated the situation. Romanian Jews exhibited lower levels of cultural assimilation compared to even their recently immigrated Hungarian Jewish neighbors. One Jewish historian, Nicholas Nagy-Talavera, admits that:

“These Jews, being of a primitive, 'religious-nationalist' type, refused any association or solidarity with the new Romanian state, whose violent, romantic nationalism was inconceivable to them, [and] did not endear them to the local population.”

— Nicholas Nagy-Talavera

The prevailing anti-Semitic sentiment in Romania during the interwar period can be discerned from the fact that even the most liberal and bourgeois statesmen maintained a staunchly anti-Semitic stance. With a few exceptions, the majority of noteworthy politicians during this time harbored varying degrees of anti-Semitism. This attitude permeated not only the political sphere but also the intellectual and literary circles, as well as the wider Romanian society, including peasants, the emerging middle class, and the working class.

In 1879, just two years after Romania gained independence from the Ottoman Empire, the renowned and influential Romanian poet Mihai Eminescu expressed the belief that "the Jew does not deserve rights anywhere in Europe because he does not work…. He is the eternal consumer, never a producer." This sentiment echoed the prevailing views held by the majority of Romanians. This attitude did not undergo significant changes following the conclusion of the Great War. In fact, a mere two days after the armistice on November 11, 1918, the Romanian government framed its invasion of Bela Kun's short-lived communist Hungary as an explicitly anti-Semitic crusade, intertwining Judaism and Communism in their propaganda.

Despite the shared self-identification as nationalists, politicians in Romania at the time often diverged in their policies and sensibilities. However, they all sought to justify their actions and proposals based on what they believed to be in Romania's best interests. Exceptions to this trend included ethnic particularist parties and the Stalinist Communist party. Notably, a faction emerged during the interwar period that epitomized an extreme form of nationalism. The historian Roland Clark terms them the “ultranationalists” and he describes them as follows:

“Ultranationalists embraced the central ideas of Romanian nationalism that had been developed during the nineteenth century, even while they rejected many mainstream intellectuals as Westernizers. They saw Romanians as a downtrodden but noble people who had lived under foreign oppression for centuries. Romanian nationalism was a moral imperative for them, and required sacrificing time, money and if necessary, respectability. They blame “politicianism” for their country’s economic and social woes and charged that the democratic parties had sold Romania out to foreigners. In the ultranationalist imagination, the quintessential foreigners were Jews, whom they considered the ethnic, religious, economic, and social enemies of their people. They advocated expelling Jews from the country. They believed that the solution to Romania’s problems lay in cultivating autochthonous Romanian “traditions” and not in foreign imports, but that Romanians themselves needed to be reformed through discipline and sacrifice.”

— Roland Clark

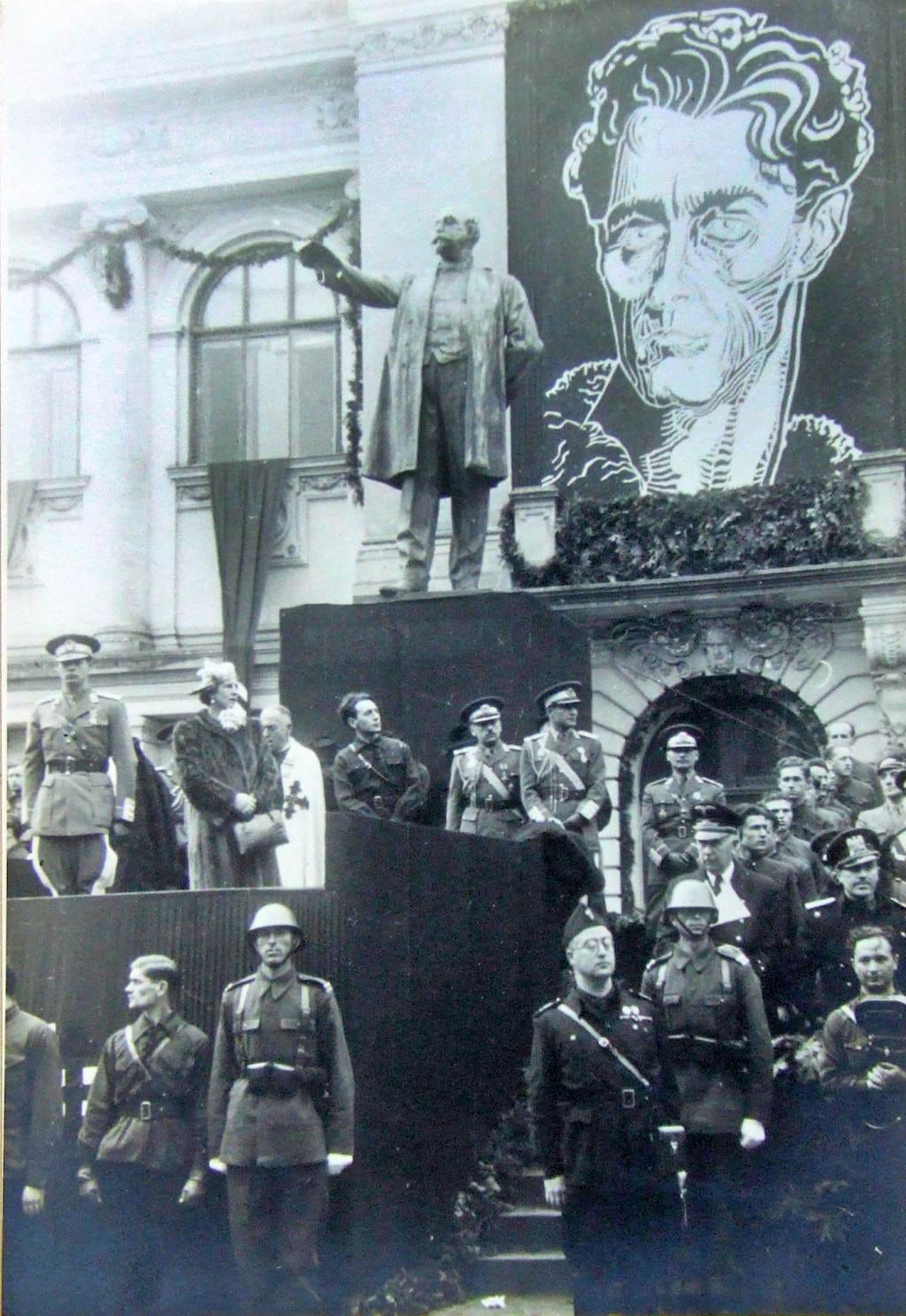

Following World War I, Romanian ultranationalism experienced a revival in urban areas, particularly in the city of Iasi. The government's Romanianization programs played a significant role in this resurgence, as they provided opportunities for many students to become the first in their families to attend university. Among these students were future leaders of the Legionary or Iron Guard Movement, with one notable figure being Corneliu Codreanu, who has rightfully become synonymous with Romanian Fascism.

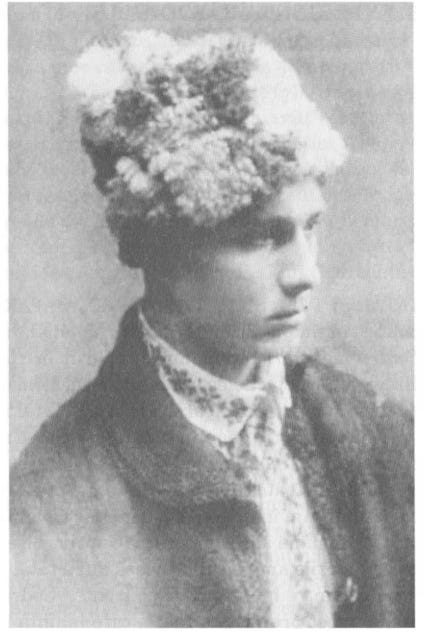

The Young Codreanu

Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, born in 1899 in the city of Husi, came from a family with an ethnically German mother and a Romanian father. Despite his German heritage, Codreanu and his family seamlessly assimilated into Romanian society. From my extensive research on the subject, it appears that their background was rarely, if ever, an issue, except for a few isolated cases that were not taken seriously by the majority. In fact, Codreanu's father, Ion Codreanu, was well-respected within Romanian ultra-nationalist circles even before the Great War, and there seemed to be no hindrance or objection regarding his background or his marriage to an ethnic German woman.

Young Codreanu

Corneliu Codreanu, like many young Romanians of his time, possessed a deep love for his country and embraced nationalist sentiments. His passion for nationalism was further nurtured by his father's influence and the ultra-nationalist literature he encountered. As a young teenager, Codreanu eagerly attempted to fight for his country alongside his father during World War I, but upon his father's advice, he ultimately enrolled in a military academy and did not experience direct combat.

After the war, Codreanu pursued a law degree at the University of Iasi, where he encountered fellow ultranationalists, as well as sympathetic professors, including A.C. Cuza, who headed the faculty of law. Cuza, a prominent Romanian political figure, had previously collaborated closely with Corneliu Codreanu's father, Ion Codreanu, in politics. It is worth noting that Cuza was known for delivering anti-Jewish speeches in the Romanian parliament even before Hitler's rise to power.

However, the realm of politics extended beyond the university campus. In Iasi, there were other ultranationalists, among whom Constantin Pancu and his "Guard of National Consciousness" stood out. Codreanu joined this organization shortly after arriving in Iasi for his studies in the autumn of 1919. It marked Codreanu's initial foray into political activism.

Regarding the ideology of the Guard, it explicitly identified itself as anti-Communist while advocating for a "National-Christian Socialism." In describing Pancu, Codreanu favourly recalled:

“[That] He [Pancu] was a tradesman, plumber and electrician. He never went beyond four primary grades. He had a lucid, balanced mind which he himself enriched with adequate knowledge. For twenty years he had been occupied with workers' problems. He had been for several years the president of the metallurgical union. He was a first class speaker. At the podium, before a crowd, he was impressive. He had a soul and a conscience that were clearly Romanian. He loved his country, the military, and the King. A good Christian. He had the muscles of a circus fighter and was truly Herculean.”

— Corneliu Codreanu

In contrast to the ultranationalist movement, there was a noticeable rise of communist and leftist influence in Iasi during the aftermath of World War I. Although communism would not firmly establish itself in Romania, even among intellectuals and artists, until after the Second World War, there was a brief period in the Moldavian region, centered around Iasi, where communist and leftist activities gained traction. This new wave of influence spread among students, teachers, and workers in the city. Leftist labor unions were active in Iasi, and many student organizations at the university were led by communists.

During this post-war period, Romania, like many other countries, faced significant economic and social challenges. The communists were quick to exploit the industrial unrest that arose as a result. In response to these left-wing labor unions, Constantin Pancu and the members of the Guard established their own nationalist unions throughout the city, competing with the socialists. This often led to situations where they would work as strikebreakers during strikes organized by leftist unions. However, the issue for Pancu and Codreanu was not the concept of strikes or labor unions or workers' rights per se. Their concern lay in the communists utilizing these methods to further their anti-nationalist agenda.

The Guard consistently maintained a pro-worker stance and advocated for workers' rights, but always within a national context. They believed in the importance of preserving the nation and saw workers' rights as inseparable from this goal.

"It is not enough to defeat Communism. We must also fight for the rights of the workers. They have a right to bread and a fight to honor, We must fight against the oligarchic parties, creating national workers organizations which can gain their rights within the framework of the state and not against the state."

— Corneliu Codreanu

While actively engaged in fighting against the communists in the city, Codreanu also played a significant role at the university level. Along with other nationalists in various universities, Codreanu advocated for the implementation of Numerus Clausus, a policy that would limit the number of Jewish students in universities. This policy had already been established in a few European countries and was a long-standing goal for Professor Cuza.

Under Cuza's guidance, Codreanu formed a close-knit group of like-minded Romanian students. When they learned that the university would not begin the academic year with a religious service as they had traditionally done, they became incensed. On the first day of the school year, Codreanu and a few others physically blocked the entrance to the university in protest. Although students and professors eventually managed to enter, the university decided to hold the inauguratory religious service later that same week. Codreanu and his nationalist comrades frequently clashed with students, professors, and city residents, engaging in violent altercations such as disrupting a Jewish play production, assaulting Jewish newspaper editors, and stealing the distinct Bessarabian hats worn by foreign, often leftist, students.

In the spring of 1920, they even garnered enough votes in the all-Romanian Student Congress to exclude Jews from Romanian student clubs in all universities, effectively reclaiming ground from communist students.

However, Codreanu would eventually face expulsion from the university due to his actions. A concerned student wrote a letter urging the university to take this step, expressing their disapproval of Codreanu's behavior.

“His behavior has found imitators, and now Mr. Codreanu has about ten of fifteen lackeys, who distinguish themselves by the noise they make at student gatherings, but none of whom is as impulsive as Mr. Codreanu. Mr. Codreanu is the one who provoked all the scandals and misunderstandings in our student life… in view of all these things, Mr. Rector, we ask that you give the most severe sanctions for the purification of student life.”

—

Despite facing expulsion, Codreanu's fate took an unexpected turn due to the influence of Professor Cuza and other faculty members sympathetic to his cause. As a result, Codreanu was permitted to complete his studies in the school of law and was awarded a certificate by the school in place of an official diploma.

Codreanu's expulsion and his involvement in various activities had brought him considerable notoriety. This newfound recognition led to his election to the Law Students' Association, where he established a weekly reading group with an anti-Semitic focus. Furthermore, Codreanu founded "The Association of Christian Students" with the aim of countering the dominance of leftist student societies.

Codreanu’s Observations in Germany

After completing his studies in Iasi, Codreanu embarked on a year-long journey to Germany to further his education in Berlin and Jena. However, according to Codreanu's own account, the purpose of his study abroad extended beyond mere academic pursuits. He expressed his thoughts on the matter, stating:

“I shared with my comrades an old thought of mine, that of going to Germany to continue my studies in political economy while at the same time trying to realize my intention of carrying our ideas and beliefs abroad. We realized very well, on the basis of our studies, that the Jewish problem had an international character and the reaction therefore should have an international scope; that a total solution of this problem could not be reached except through action by all Christian nations awakened to the consciousness of the Jewish menace.”

— Corneliu Codreanu

It was during his time in Germany that Codreanu received news of Mussolini's triumph in Italy.

“I rejoiced as much as if it were my own country's victory. There is, among all those in various parts of the world who serve their people, a kinship of sympathy, as there is such a kinship among those who labor for the destruction of peoples. Mussolini, the brave man who trampled the dragon underfoot, was one of us, that is why all dragon heads hurled themselves upon him, swearing death to him. For us, the others, he will be a bright North Star giving us hope; he will be living proof that the hydra can be defeated; proof of the possibilities of victory.”

— Corneliu Codreanu

Codreanu even remarked on Mussolini's apparent lack of anti-Semitism, which was a fundamental aspect of his own Romanian nationalism.

“But Mussolini is not anti-Semitic. You rejoice in vain," whispered the Jewish press into our ears. It is not a matter of what we rejoice in say I, it is a question of why you Jews are sad at his victory, if he is not anti-Semitic. What is the rationale of the worldwide attack on him by the Jewish press? Italy has as many Jews as Romania has Ciangai [a quite minor ethnic group] in the Siret valley. An Italian anti-Semitic movement would be as if Romanians started a movement against the Ciangai. But had Mussolini lived in Romania he could not but be anti-Semitic, for Fascism means first of all defending your nation against the dangers that threaten it. it means the destruction of these dangers and the opening of a free way to life and glory for your nation. In Romania, Fascism could only mean the elimination of the dangers threatening the Romanian people, namely, the removal of the Jewish threat and the opening of a free way to the life and glory to which Romanians are entitled to aspire. Judaism has become master of the world through Masonry, and in Russia through Communism. Mussolini destroyed at home these two Judaic heads which threatened death to Italy: Communism and Masonry. There, Judaism was eradicated through its two manifestations. In our country, it will have to be eradicated through what it has there: Jews, communists and masons. These are the thoughts that we, Romanian youth in general, oppose to Judaic endeavors to deprive us of joy in Mussolini's victory.”

— Corneliu Codreanu

During his time at universities in both During his time in Berlin and Jena, Codreanu was not impressed by the student movements he observed. He expressed his sentiments, stating:

“There were in Germany several anti-Semitic political and doctrinaire organizations, with papers, manifestoes, insignia, but all of them feeble. Students in Berlin, as those in Jena, were divided in hundreds of associations and numbered very few anti-Semites. The student mass knew the problem but vaguely. One could not talk of an anti-Semitic student action or even of a doctrinaire orientation similar to that of Iasi. I had many discussions with the students at Berlin in 1922, who are certainly Hitlerites today, and I am proud to have been their teacher in anti-Semitism, exporting to them the truths I learned in Jasy”

— Corneliu Codreanu

It was also during his time in Germany that Codreanu recalls hearing about Hitler for the first time.

“I heard of Adolf Hitler for the first time around the middle of October 1922. I had gone to a worker in North Berlin with whom I established a good relationship, who was making "swastikas." His name was Strumpf… He told me: "It is said that an anti-Semitic movement has been started in Munich by a 36 year old painter, Hitler. It seems to me he is the man we Germans have been waiting for." The foresight of this worker was fulfilled. I always admired his intuitive powers by which he could select with the antennae of his soul, a stranger among scores of men, ten years before his time, the one who would succeed in 1933, uniting under a single great command the entire German people.”

— Corneliu Codreanu

Romanian Third Positionism Before Codreanu

While Codreanu played a pivotal role in the development of Romanian Third Position ideology, he was not the sole figure involved in this movement.

Another notable figure was Elena Bacaloglu, a journalist and Pan-Latin activist, who founded the "Italian-Romanian National Fascist Movement" in 1921. It is remarkable that Bacaloglu engaged in politics during a time when Romanian women did not have the right to vote. By the early 1920s, her movement had established local branches throughout Romania. An interesting aspect of Bacaloglu's group was its strong stance on the Jewish connection to both Communism and Capitalism, which diverged from the non-racial emphasis of traditional Italian Fascism. Eventually, Bacaloglu's movement merged with the "National Romanian Fascio." However, due to leadership issues, the group disbanded in 1924, despite having achieved a substantial membership base at its peak.

Elena Bacaloglu

Historian Roland Clark describes the policies of the Italian-Romanian National Fascist Movement by stating:

“[They] promised to overcome politicianism through a radical reorganization of the state. They proposed forming vast corporations that would govern factories, the railways, the postal service and other major enterprises before beginning an expansive public works project to increase the roads and railway systems, to build irrigation canals, and to further exploit Romania’s oil supplies. They promised to guarantee private property while nationalizing all landed estates larger than 100 hectares, to simplify the taxation system and to cut the number of state functionaries by a third. At the same time they spoke about the need to expand the schooling system and to overcome illiteracy.”

— Roland Clark

Similar to the dynamics witnessed at the University of Jasy under Codreanu's influence, the Transylvanian University of Cluj emerged as another fervent hub of nationalist activity. This city, acquired by Romania after the war, served as the backdrop for Ion Mota's eventual co-founding of Action Romania in 1924, alongside several members of the defunct National Romanian Fascio. Drawing inspiration from Charles Maurras' French proto-Fascist and Corporatist movement, known as "Action Francais," the group embarked on translating and disseminating anti-Semitic and nationalist literature in Romanian. Notably, Mota himself undertook the translation of the Protocols of The Elders of Zion from French to Romanian. However, their impact remained confined primarily to the Cluj region, eventually merging with a larger nationalist movement.

What distinguishes these groups is the remarkable diversity of their membership, encompassing individuals from various social strata, including peasants, the working class, students, priests, professors, journalists, and even esteemed veterans.

Nevertheless, it was the ultranationalist "National Christian Union," founded in 1922 by Professor Cuza and centered in the city of Jassy and its surrounding region, that wielded considerable influence through its prestigious membership within Romanian society.

While Codreanu played an active role in organizing ultranationalist activities in Jasy, he was just one among numerous student organizers in Romania. During his sojourn in Germany, a nationwide protest unfolded among students from universities and high schools, accompanied by a significant contingent of professors and teachers. Originating in Cluj, these students engaged in protests, targeting the press, engaging in altercations with Jewish students, and resorting to other acts of violence.

The students articulated multiple demands. Initially, medical students in Cluj protested against Jewish students' right to dissect Christian cadavers. However, as the protests gained momentum, their objectives expanded. Romanian students began advocating for a numerus clausus policy to restrict the number of Jews in universities, imposing sanctions on the Jewish press for insulting Orthodoxy and the Romanian state, ceasing Jewish immigration, prohibiting Jews from changing their names, improving living conditions in dormitories, and securing increased funding for their universities.

Initially sporadic, the protests gradually intensified in frequency and scale, notably surging during the autumn of 1922. On December 10, 1922, a day etched into their collective memory, students in Romania's three major cities—Bucharest, Cluj, and Jasy—declared and effectively executed a general strike against their respective universities.

In reflecting on the movement's spontaneity, Ion Mota eloquently remarks:

“This or that particular student [that] gave birth to the movement. It was born spontaneously from the soul of the mass of students, superimposed on the soul of the nation. Without any kind of preliminary organization or premeditation. And the proof that it did not start from a few isolated spirits, who might have been sick or degenerate, is the fact that with lighting speed, it was recognized by the entire body of university youth -- with insignificant expectations -- as being the mirror of their own spiritual process. Those who criticize this past, therefore, do nothing but protest against an organic social phenomenon of a suffering nation: they criticize a spasm, they criticize a generation, which precisely out of healthy feeling and thought, did not deign to break itself from the body of the nation, but received its pulsations of life and for life.”

— Ion Mota

In a desperate attempt to regain control, the universities resorted to deploying the police to suppress the student unrest. However, the situation quickly spiraled out of their control, leading to the closure of the universities and the expulsion of students. The news of the students' general strike, emanating from Germany, prompted Codreanu to return to Romania with the intention of joining his comrades in the fight.

The intensity and widespread nature of the student activism reached such heights that most students ceased attending classes altogether. The government, recognizing the gravity of the situation, dispatched the military to restore order. Yet, this measure proved only partially effective, as the sympathies of some military personnel lay with the protesting students, leading them to join and support the demonstrations. Both the universities and the government found themselves in dire straits. When classes eventually resumed, only a handful of students would attend, with the majority being Jewish students who would endure mistreatment at the hands of their protesting peers or face the disruptive noise of the protests taking place just outside the classroom.

Ultranationalist Solidification

Upon his return to Romania, Codreanu wasted no time immersing himself in the student movement. He traversed the country, engaging with students and persuading them of the significance of the protests, emphasizing that they were more than mere materialistic demands for improved funding and better living conditions. Codreanu's primary concern was that if the universities were to partially concede to the economic demands, the students might abandon the Jewish question and settle for what they were given.

In his efforts to organize and channel the radical energy of the student protests, Codreanu entered into discussions with Professor Cuza, a figure of immense ideological and personal inspiration to the students. Codreanu proposed the creation of an organization to better structure and mobilize the movement. However, Cuza initially rejected the idea, believing that a mass movement was sufficient. Codreanu countered by likening a mass movement to an oil well that, without a pipeline, would ultimately be futile as the oil would spill everywhere. Ultimately, it was through the persuasive efforts of others, including his long-time associate Ion Codreanu, that Cuza relented and agreed to form the new group.

On March 4, 1923, the National Christian Defense League, known as the LANC, was founded amid a grand rally attended by students and delegates from various student organizations across Romania. The LANC emerged through the merger of Cuza's own traditional political party, the National Christian Union, with several other groups. Later on, additional nationalist groups, as well as members from disbanded fascist organizations like Romanian Action and The Romanian National Fascio, would also join the LANC. The primary focus of the LANC was to address the Jewish question, which had been a lifelong concern for Cuza. As a testament to this, the LANC adopted a flag featuring the Romanian tricolor with a Swastika at its center, a symbol introduced by Cuza himself that was seen as embodying the anti-Semitic struggle in Europe.

Codreanu assumed the position of secretary general of the league and took charge of organizing the student wing. He dedicated his time to recruiting, organizing events, and developing principles and guidelines for chapter leaders to follow. These organizational skills would prove invaluable to him in the future.

Simultaneously, Romania was in the process of drafting a new constitution. The ultranationalists were particularly concerned by the civil and political rights that would be granted to Jews and other Romanian minorities. Adding to their frustration, this constitution was imposed upon Romania as a result of the World War One peace treaties, despite Romania being on the winning side. The intention behind these treaties was to "Make the world safe for democracy." To the ultranationalists, the ratification of the new constitution mere weeks after the founding of the LANC dealt a significant blow to the morale of the student movement, which was still engaged in an ongoing general strike.

Disheartened by their failure to achieve a Numerus Clausus policy and with the implementation of the new constitution, Codreanu and a small group of close associates hatched a poorly planned scheme to assassinate several influential Jewish individuals and Romanian politicians whom they held responsible for the constitution. However, before they could put their plans into action, a member of their conspiracy alerted the police. Consequently, all the conspirators, including those suspected of aiding them, such as Codreanu's father, were arrested in October 1923.

Codreanu’s Rise to Prominence

After their acquittals and the trial that catapulted them into the national spotlight, Codreanu and several LANC members embarked on plans to construct a meeting place and headquarters in Jasy. They undertook the labor themselves and raised funds to acquire the necessary materials, often receiving discounts or even donations from sympathizers of their cause.

However, just weeks after peacefully working on the new student center, Codreanu and the others were arrested by the police. They were subjected to interrogations and, according to personal accounts from Codreanu and his fellow students, even torture. It is worth noting that police prefects at the time were political appointments, and Constantin Manciu, the police prefect responsible for Codreanu's arrest, was specifically chosen to suppress the student movement in Jasy. This included the arrest of students and the involvement of the military to quell student rebellions, further fueling the antagonistic relationship between the police and the students. The students were never officially charged or arrested but were held for police interrogation.

Following their release, several students and their parents, many of whom were still in high school, brought Manciu to trial for corruption, armed with medical examinations as evidence. However, on the first day of the corruption trial against the police prefect, Codreanu, having been rushed by Manciu outside the courthouse and feeling threatened, shot and killed him. This led to Codreanu's arrest once again. However, similar to his first arrest, there was a significant surge in support for Codreanu and the LANC.

Roland Clark describes the ensuing scene:

“As it had a year earlier, the ultra-nationalist community rose in his defense, sending money, writing petitions, and filling its newspapers with supportive articles. Thousands of people sent forms to the president of the jury requesting that their names be recorded as Codreanu’s defenders. Students protested first in Iaşi and then in Bucharest, where they distributed pamphlets defending Codreanu and staged demonstrations in his support.”

— Roland Clark

And the Historian Eugene Weber writes:

“Aware that public opinion was on Codreanu’s side, the authorities decided to hold his trial away from Iasi: first in another Moldavian town, then at the other end of the country, at Turnu Severin… But even there the trial turned into a triumph, with trainloads of sympathizers pouring into town, even forucin the tribunal to abandon its courtroom for the local theater, itself hardly sufficient to hold the public…. The Jury stayed out exactly five minutes, and returned sporting on their lapels the LANC emblem -- the national colors with a swastika on top.”

— Eugene Weber

Once more, Codreanu and the LANC emerged victorious in the battle for public opinion against the government. The entire trial process, from Codreanu's arrest to his eventual acquittal, dealt a significant blow to the government's authority. Cities that the authorities believed were immune to ultranationalist and anti-Semitic sentiments were revealed to be highly sympathetic to the LANC's message. When Codreanu returned to Jasy, he was greeted with immense enthusiasm at every train stop, with local populations expressing their support and admiration for him. The widespread fanfare demonstrated the deep resonance of the LANC's ideology among the people.

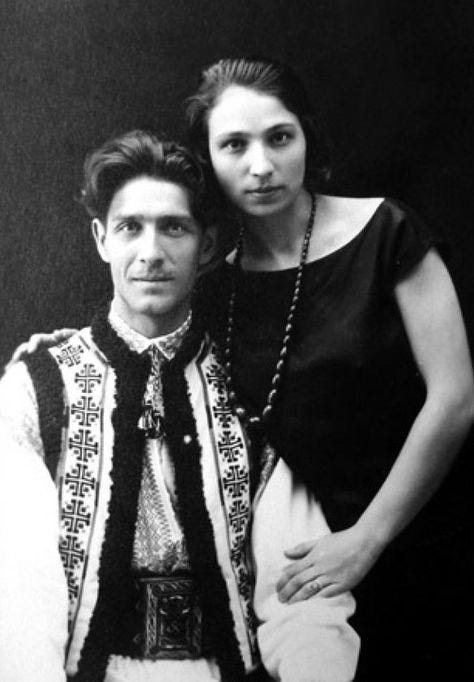

Codreanu and his wife

Building on his growing prominence, Codreanu and his fiancé Elena held their wedding in June 1925, just weeks after his acquittal. The wedding, much like the trial, was turned into a grand propaganda spectacle. It quickly gained national attention, with an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 people from all over the country attending the event. To put this into perspective, in terms of population percentages, it would be equivalent to approximately 1,500,000 people attending a similar event in the United States today. Additionally, around 100 families chose to baptize their newborn children with the name Corneliu at the wedding, further highlighting the significance and influence of Codreanu.

The wedding was even captured on film, a rarity in Romania at that time. Unfortunately, all known copies of the film were later destroyed by the government. It remains unclear whether this occurred before or during the Communist period.

Revolutionary vs Bourgeois Nationalism

Despite the LANC's growing popularity and positive publicity, conflicts and tensions were beginning to arise within the organization, particularly between Codreanu and AC Cuza. Returning to work full-time for the LANC after his trials and wedding, Codreanu started to realize the divergence of their visions. The essence of the conflict was that Cuza was just a good anti-Semitic bourgeois who wanted a political party on a democratic basis. Beyond ideological differences, there were also disparities in their organizational philosophies.

Cuza envisioned the LANC as a traditional political party that would gain support from the masses, whereas Codreanu, recognizing the flaws of human nature, emphasized the need for organization. According to the memoirs of a former legionary, Codreanu sought a movement of moral restoration, akin to a military order, where spiritual values and a willingness to sacrifice oneself for the cause were paramount. Even Ion Codreanu, a long-time comrade of Cuza, started to clash with him. However, the tipping point may have been the personal issues between the Codreanu and Cuza families, stemming from AC Cuza's son impregnating one of Codreanu's sisters and refusing to marry her. This event, in part, explains why in 1926, both Ion Mota (who had previously married another of Codreanu's sisters) and Corneliu Codreanu, along with their wives, left to study in France when their own fame and the LANC's stature were at an all-time high. Despite this temporary break from the movement, Codreanu did not formally split with Professor Cuza and even returned to Romania to assist the LANC during an academic break.

Upon arriving in the city of Grenoble in Southeast France, Codreanu made the following observation:

“What surprised me exceedingly was the fact that this city, contrary to all my expectations, had changed into a real wasps' nest of Jewish infection. Stepping off the train I expected to see people of the Gallic race that with its unequalled bravery had marked history's centuries. Instead, I saw the Jew with his aquiline nose, thirsty for profit, who pulled me by the sleeve to enter either his store or his restaurant. In the France of the assimilated Jew everything was kosher. We entered restaurant after restaurant in order to find a Christian one, but in each we saw the sign in Yiddish: "Kosher food." Finally we found a French restaurant, where we ate. We found no difference between the [Jasy] Jews and those of Strasburg; the same figure, the same manners and jargon; the same Satanic eyes in which one read and discovered under the polite look, the avidity to gyp one.”

— Corneliu Codreanu

Despite being in France, Codreanu did not lose his political drive. In a letter written to Cuza, he expressed his concerns in a somewhat passive-aggressive manner, urging him not to exert more centralized control over the student wing of the LANC by the party leaders. This indicates that Codreanu maintained his assertiveness and commitment to the principles he believed in, even while physically separated from the movement.

Codreanu told him:

“We are always ready to defend with our own lives the honour and the life of the national defence movement, the honour and the life of its leader and of the eternal truth that he embodies and for which we swore allegiance to until our death.”

— Corneliu Codreanu

Codreanu's time in France was abruptly interrupted in the summer of 1927 when he received news from his comrades back home about the disarray and fragmentation of the LANC. They pleaded for his return, hoping that he could help salvage the organization. Upon his arrival in Romania, Codreanu found the LANC in a state of complete disaster. Cuza's leadership had caused division and conflict within the organization, further exacerbated by his decision to expel many other leaders of the LANC. A former Legionnaire described the situation as follows:

“[Cuza] was not of leadership caliber; neither was he an organizer or driving force. Rather he was a man of science and an ideologue. Extremely well qualified for matters pertaining to theory, he was ineffective and clumsy when he came into contact with reality.”

—

The Legion of the Archangel Michael

Unable to reconcile and revive the LANC, Codreanu made the decision to establish his own independent group, completely separate from Cuza. This new movement was named the Legion of the Archangel Michael. The inspiration for the name came from Codreanu's personal experience during his prison term in 1923. While in the prison cathedral on his feast day, he witnessed the presence of the Icon of the Archangel Michael. Codreanu expressed his awe and astonishment, stating,:

“We were truly amazed. The icon appeared to us of unsurpassed beauty. I was never attracted by the beauty of any icon. But now, I felt bound to this one with all my soul and I had the feeling the Archangel was alive. Since then, I have come to love that icon. Any time we found the church open, we entered and prayed before that icon.”

— Corneliu Codreanu

A depiction of arc angel Michael

The establishment of the Legion marked the official split between Codreanu and Professor Cuza, leading to their groups becoming rivals and engaging in immediate clashes. One of the primary points of contention was the ownership of the cultural center in Jasy, which the Legion claimed as its own against the Cuzists who attempted to occupy it.

However, the differences between the two factions went beyond this physical dispute. There was a deeper conflict over who represented the legitimate torchbearer of the radical student movement and ideological disparities. The LANC, under Cuza's leadership, adhered to the general mold of a conventional Romanian political party. While they employed more radical rhetoric against Jews, Cuza's focus was not on building a "movement" in the same way Codreanu envisioned. For Codreanu, the Legion was not merely a political party; it was a movement of religious revitalization aimed at creating a New Romania through the transformation of individuals rather than the implementation of new political programs. Although the Legion did field candidates and engage in political campaigning, this aspect was considered secondary within the movement.

In an article published in the first edition of the new Legionary newspaper, Ion Mota, who would later become second in command in the Legion, wrote:

“We do not do politics, and we have never done it for a single day in our lives… We have a religion, we are slaves to a faith. We are consumed in its fire and are completely dominated by it. We serve it until our last breath.”

— Ion Mota

Codreanu similarly described the new Legion as different:

“Fundamentally from all the other political organizations, the Cuzists included. All of these groups believed that the country was dying because of lack of good programs; consequently they put together a perfectly jelled program with which they started out to assemble supporters. … [But] This country is dying of lack of men, not of lack of programs …., In other words, it is not programs that we must have, but men, new men, For such as people are today, formed by politicians and infected by the Judaic influence, they will compromise the most brilliant political programs.”

— Corneliu Codreanu

The Legion of the Archangel Michael deliberately embraced a religious and spiritual orientation deeply rooted in Orthodoxy, drawing inspiration from a concept known as "Cosmic Christianity." Scholars have often referred to this form of spirituality as "peasant Orthodoxy."

“The final aim is not life but resurrection. The resurrection of peoples in the name of the Savior Jesus Christ. Creation, culture, are but a means, not a purpose as it has been believed, of obtaining this resurrection. It is the fruit of the talent God planted in our people for which we have to account. There will come a time when all the peoples of the earth shall be resurrected, with all their dead and all their kings and emperors, each people having its place before God's throne. This final moment, "the resurrection from the dead," is the noblest and most sublime one toward which a people can rise.”

— Corneliu Codreanu

While the majority of Legionaries and the Romanian population identified as Orthodox, there were also members from Greek and Roman Catholic backgrounds within the movement. Some Catholic theologians, priests, and even Protestants were known to have joined the Legion.

In contrast, the LANC, despite its Christian name, did not prioritize religious life to the same extent as the Legion. Every Legionary gathering, held in small groups called "nests" across the country, would commence with a religious service. During roll calls, when the names of deceased members and martyrs were called, the members would respond in unison with a resounding "Prezent!" signifying that although physically gone, they remained present in spirit. This concept derived from the Orthodox understanding of Sainthood, where the saints are believed to be eternally alive. As Jesus conveyed to the Sadducees in the Gospel of Luke, "For God is not a God of the dead, but of the living: for all live unto him."

On the other hand, Cuza held a less spiritual perspective. He espoused his own form of heterodox Christianity, deviating from Orthodox, Catholic, and most Protestant teachings. Cuza believed that the Old Testament should be excluded from the Christian canon due to its perceived Jewish influence. He argued that Jesus and the God of the New Testament differed from Yahweh of the Old Testament, echoing early Gnostic heresies. Cuza also drew religious inspiration from the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer and was unafraid to launch systemic attacks against the Orthodox Church. Consequently, Cuza and his nominally Christian political organizations failed to gain support from the clergy, a demographic that would later become a crucial part of the Legion's support base and mobilization efforts.

The Legion also placed a strong emphasis on personal virtue, a characteristic that was not as prevalent in the LANC. Being a member of the Legion entailed more than just being part of a political party, paying dues, subscribing to the party newspaper, and participating in occasional rallies. It was a lifestyle that aimed to transform individuals into the embodiment of the "new Romanian man."

Carlos Manuel Martins puts it succinctly:

“The ‘New Man’, … is at the core of Codreanu’s ideology, even more so than in other fascist configurations. It is Codreanu himself who says that, since the morals of Romanian men have been corrupted, ‘the cornerstone on which the Legion stands is man, not the political program; man’s reform, not that of the political programs’. Rather than composing political programs or discussing political theory, this leader has one main practical goal: to alter the nature of the inhabitants of Romania. That is the fundamental aim at the basis of his political activity.”

— Carlos Manuel

And in a similar vein historian Rebecca Haynes writes:

“Codreanu’s vision of the legionary ‘New Man’ was intimately connected to his attitude towards the Romanian political establishment and the Jewish minority. The Jews, he believed, were only able to dominate Romanian society owing to the moral failings of the Romanians and the consequent corruption of their political elite. ‘A country has only the Jews and the leaders it deserves’, he wrote. It followed that political life could not be transformed by party programmes unless individuals were first perfected by a return to Christian morality, discipline, and love of nation. Codreanu wrote, ‘presupposes in the first place, and as an indispensable element, a new type of man.’ Since this ‘New Man’ would be forbidden from entering any political party, the political elite would be starved of ‘young blood’ and eventually crumble.”

— Rebecca Haynes

Besides just the way academics have viewed the Legion, when a former Legionary was asked what its core principles was he responded:

“Perfection through virtue, respecting life's original harmony; subordination of matter to spirit; installing "a forceful Christian faith, an unlimited love of country, correctitude of soul as the expression of honour, and unity as the premise for success.

These are the pillars of Codreanu's school which were based on the foundation of 'the rule of the spirit and moral value.' The Legion endeavored to create a national elite of character leading to an aristocracy of virtue sustained by love of country and permanent sacrifice for the Fatherland, on justice for the peasantry and the working man, on order, discipline, work, honest dealing, and honour.”

—

During Legionary meetings, members would frequently engage in discussions about their personal struggles and sins, openly sharing and seeking support from one another. As a means of atonement, they would assign punishments to themselves. Additionally, Legionaries were expected to contribute both their time and financial resources to the movement, while also adhering to certain physical requirements.

The Legion operated with a more structured and hierarchical framework, characterized by a rigid chain of command. It was not simply a mass movement, as Cuza was accused of desiring. The Legion placed importance on discipline, organization, and clear lines of authority. This structure allowed for efficient decision-making and effective implementation of the Legion's goals and principles.

The Legion of the Archangel Michael had a system in place that allowed high school students as young as 14 to join a group known as the "Legion of Friends." Those who proved themselves within this group could then advance to join the "Blood Brotherhood," which consisted of older high school students who gathered once a week. For those who had completed high school, there were nests where groups of 3 to 13 Legionaries regularly met.

These meetings, led by Nest leaders and guided by a handbook written by Codreanu, involved a range of activities and instructions. Members discussed and planned future activities, assessed their progress from the previous week, sang songs, collected donations, read from the Bible, and paid tribute to fallen Legionaries. Notably, these meetings blurred the lines between politics and religion to the point where the distinction was almost nonexistent. Both political discussions and religious practices were intertwined, emphasizing the Legion's holistic approach to creating a New Romania.

There were 6 rules rules of life outlined, for those in the nests:

“(1) the rule of discipline, to follow the nest leader through thick and thin; (2) the rule of work, not only to work but also to love work, not for the sake of gain, but for the satisfaction of having done one’s duty; (3) the rule of silence, to be frugal with words; the speech of a Legionary must be action, he must let others act like chatterboxes; (4) the rule of self-education; the Legionary must become through it a heroic man; (5) the rule of mutual aid; Legionaries must not ever abandon each other, and finally, (6) the rule of honor; a Legionary must always act honorably — even honorable defeat was preferable to dastardly victory.”

— Next Leaders manual

There were likewise a similar purpose outlined for the fortresses, the female equivalent of the nests:

“a) The self-improvement of fortress members everywhere; b) To support the Legion in every way possible; c) To create and promote the morale of women; d) To develop and maintain an active life, the Christian traditions of our ancestors, consciousness and national solidarity among all Romanian women; e) To give the new Romania a new woman, a seasoned and resolute warrior.”

— Nest Leaders manual

Despite initially consisting of a small group of just 20 students, the Legion of the Archangel Michael experienced rapid growth and expansion. They were successful in recruiting and convincing numerous leaders and influential members from the LANC to join their cause. As a result, nests and fortresses, the Legion's organizational units, began to spread throughout Romania.

The Legion's ability to attract leaders and influential individuals from the LANC played a crucial role in their expansion and influence. These new recruits brought their networks and resources, contributing to the Legion's growing presence across the country. With the establishment of nests and fortresses, the Legionary movement gained a geographic reach, solidifying its presence and impact on Romanian society.

This period of growth marked a significant milestone for the Legion, as they rapidly transformed from a small group of students into a formidable force with a widespread presence in Romania. Their ability to recruit and win over leaders and influential members from the LANC further bolstered their ranks and increased their influence within the political landscape of the time.

Legionary Funding

The Legion frequently faced financial challenges and actively sought ways to generate income. According to Dr. Roland Clark, the primary source of revenue came from "Financial contributions from members," which were crucial for the Legion's operations. To supplement this, the Legion established different avenues for fundraising, such as the "Committee of One Hundred," which allowed government employees unable to join political organizations to contribute anonymously.

Occasionally, the Legion received donations from the Romanian upper class, including the aristocracy, wealthy businessmen, and industrialists. However, they did not receive any significant financial support from foreign sources.

To raise funds, the Legion engaged in various activities, including door-to-door campaigns, organizing balls and dances, collecting scrap metal, selling legionary songbooks, newspapers, books, and showcasing crafts made by women in the fortresses, such as flags, embroideries, and other Legionary artwork.

Furthermore, the Legion derived a significant portion of its income from a network of businesses spread throughout Romania, encompassing repair shops, grocery stores, restaurants, and cafes.

In a circular from 1935 Codreanu wrote that:

"Legionary business is Christian business, founded upon love of man, not on theft; a business based upon honour … For the first time, the legionary faith is going to involve itself in the field of business. We have been subconsciously suffering the effects of a deviant mentality and living under its tyranny: the Romanian is no good in business. Today, we want to destroy, to break this mentality and show that, on. this path also, the legionary will be the victor."

— Corneliu Codreanu

To save on cost, these businesses were The Legion often relied on volunteers, which had the additional advantage of showcasing the inclusive nature of legionary life by breaking down class barriers. It was not unusual to find college students, lawyers, engineers, or even college professors waiting tables for peasants or industrial workers, and this intentional mix of social classes exemplified the Legion's commitment to promoting class harmony and collaboration on a national scale. This ideology rejected the class conflict advocated by Marxists and was a cause that Codreanu passionately advocated for alongside Constantin Pancu during his youth. Codreanu believed that all new Romanians should be equal based on their shared faith and heritage.

While several legionary businesses operated at a loss, their primary purpose was to attract followers rather than generate profit. These businesses were particularly prevalent in industrial areas and strategically located near factories to appeal to industrial workers. Due to their higher incomes, these workers often donated significantly more to the Legion compared to peasants.

The Legion embarked on another initiative by establishing a network of work camps throughout Romania. These camps served multiple purposes, including infrastructure repairs, church reconstruction, agricultural assistance, and the construction of Legionary buildings. However, these camps were more than just practical endeavors. They also served as platforms for Legionary rituals and propaganda, with daily events featuring singing, religious services, and oath-taking. For the Legion, these camps were not only about constructing bridges, roads, and churches; they were also about shaping the new Romanian individual.

During the program's peak, tens of thousands of legionaries were dispersed across thousands of work sites throughout Romania. People from various social classes and regions of Romania worked side by side as equals, embodying the principles of the Legion. These camps fostered a sense of unity and solidarity among the participants, transcending societal divisions and reinforcing Legionary ideals.

Expansion and Electoral Success

In addition to recruiting students and former LANC members, the Legion turned its attention to the rural peasants in the countryside. Beginning in November 1928, Legionaries, lacking the means to afford cars, set out on foot in pairs to various villages across Romania. Their purpose was to distribute propaganda and establish a presence among the newfound supporters in these villages. Although growth in the early years was slow, the Legion consistently made progress, steadily expanding its influence. Over time, they began utilizing horses for travel and organizing political rallies dressed in traditional folk clothing, actively engaging with the peasants, even working alongside them in the fields.

To broaden their appeal and navigate around authorities who often imposed bans or limitations on the Legion of the Archangel Michael, the Iron Guard was formed. This served as both a means to incorporate other nationalist groups and as a way to bypass restrictions. Under the umbrella of the Iron Guard, the vanguardist Legion maintained its organizational structure, while a new paramilitary organization was established, similar to other fascist paramilitary groups in interwar Europe. Although technically distinct, the term "Iron Guard" became synonymous with "The Legion," both in common parlance at the time and in modern academic writing. However, Codreanu and his followers predominantly referred to themselves as the Legion.

In 1931, the Legion made its initial foray into electoral politics. Lacking the resources to afford cars, Legionaries delivered speeches on horseback, dressed in peasant attire, and lived and worked alongside sympathetic peasants in their homes. This campaign style starkly contrasted with mainstream parties that would arrive in villages by car, deliver their speeches, and swiftly move on to the next location.

In writing about Codreanu’s 1931 electoral strategy Paul Kenyon wrote:

“Typically, Codreanu campaigned on foot and on horseback, dressed in peasant clothes. Arriving unannounced in market squares, he would ask locals to kneel and pray, and speak to them in mystical terms unlike any politician they had heard before.”

— Paul Kenyon

In the 1931 election, the Legion achieved a modest electoral victory, receiving 30,000 votes, which accounted for one percent of all votes cast. In comparison, the LANC had secured over 100,000 votes, representing four percent of the electorate. In an unexpected upset, Codreanu won a single seat for his party in a district near Jassy. Notably, his campaign received financial support from King Carol himself, who sought to gain the political backing of the fledgling Legion.

However, parliamentary life did not align well with the Legion's objectives, as they deliberately distanced themselves from traditional political parties and avoided discussions on government policies and programs. Despite being regarded as a mediocre public speaker, Codreanu captivated people with his enigmatic persona and sharp intellect. He drew attention in parliament by advocating for the death penalty for the misuse of state funds and publicly naming politicians who had received suspiciously large "loans" from private banks. The accused politicians nervously and unconvincingly claimed they would repay the loans.

New elections were called in 1932, and the Legion continued to experience growth. They won five seats, receiving approximately 2.5 percent of the national vote, primarily campaigning in select parts of Romania. According to historians, this election marked the last fair election in Romania until after the Communist period. Subsequent elections were marred by widespread fraud, ballot stuffing, voter intimidation, and bribery with public funds. Additionally, the rules of the Romanian parliament guaranteed bonus seats to any party receiving 40 percent of the vote, ensuring a parliamentary majority. Frequent elections during this period were a consequence of government instability, exacerbated by the global depression, which led to a sharp decline in government revenues and average income. Living standards plummeted to pre-World War I levels, with peasants facing mounting debts and falling agricultural prices. Similar to the German National Socialists, the Legion benefited from the economic downturn. The depression not only provided the Legion with a receptive audience seeking radical solutions, but it also allowed unemployed students and graduates to dedicate themselves fully to the Legion.

The year 1933 marked a turning point for the Legion. They made significant efforts to appeal to industrial workers in urban areas and even established a union for waiters. The government's response to their growing influence became increasingly suppressive. For example, when the Legion attempted to erect a cross on the tomb of the unknown soldier, they faced opposition from the police, turning the incident into propaganda material. Similarly, when the Legion listened to local needs and attempted to build a dam, they were once again met with police interference and harassment of the volunteers.

However, all these events paled in comparison when, just days before the December election, the Legion was officially banned by the national government. Around 18,000 Legionaries were arrested, and eight were killed in the process, rendering the Legion unable to participate in the election. Fearing for his life, Codreanu went into hiding. In a retaliatory act against the oppressive regime and other grievances, three Legionaries shot and killed Prime Minister Ion Duca in late December. This led to further crackdowns and arrests of Legionaries.

Similar to when Codreanu had shot the police prefect, the murderers were praised, and the act only enhanced the Legion's reputation. Some historians even speculate that King Carol II at the time may have been involved in the plot. Regardless of his involvement, the King, who had never held a favorable opinion of Duca, did not attend his funeral. Several mainstream politicians even praised the Legion and attempted to use the occasion to establish connections with them. In a show of solidarity, Mussolini sent lawyers to defend the assassins, known as the "Nicadorii." Codreanu, who had no knowledge of the plot as he was in hiding, was acquitted at his trial. However, the others, while receiving sympathy from the soldier-jury for their cause, were ultimately sentenced to a lifetime of hard labor after being tried in a military tribunal, as the government had learned from past experiences.

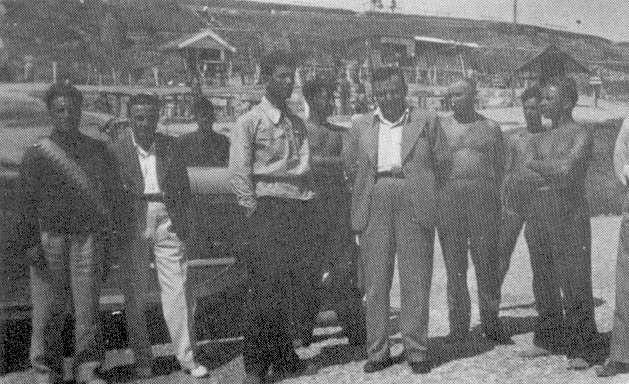

Nicadorii on Trial

Ideology and Transnational Solidarity

Prior to 1938, the Legion of the Archangel Michael had limited international outreach, although they did establish an international branch on paper to connect with the Romanian diaspora. However, they did have Ion Mota serving as the Legion's correspondent for the anti-Semitic news agency Welt-Dienst (World Service) based in Germany.

Despite their limited international presence, the Legion, particularly Mota, strongly identified themselves as part of the broader anti-Semitic and ultranationalist struggle worldwide. This was evident in Codreanu's initial visit to Germany and the Legion's connection to Mota's role. Even before the Legion's formation, Mota had accompanied AC Cuza to an anti-Semitic conference in Hungary, where he spoke positively about the experience and how warmly the Romanians were received.

This, the scholar Raul Crostecea notes:

“It is quite remarkable coming from a Transylvanian who was the son of a nationalist condemned to death during the war by the Austro-Hungarian Empire and who always remained suspicious of Hungary and its revisionist claims.”

— Raul Crostecea

Even years after the conference, Mota continued to emphasize the shared brotherhood between Hungarians and Romanians in their Christian faith and their struggle against Jewish dominance. He expressed his desire for a "brotherhood with all nations against the Jews." In 1929, Codreanu even attempted to arrange a meeting with the German NSDAP and sent Hitler a congratulatory telegram following the annexation of Austria. When accused by the governing party of being influenced by Hitler's foreign policy, Mota denied it but also praised Chancellor Hitler for eradicating Marxism and the libertarian philosophy of the French Revolution.

As early as 1931, Codreanu explained the Legion's foreign policy stance to the Romanian parliament, which was predominantly composed of establishment Francophiles. He stated that if forced to choose between two extremes, the Legion aligned with those who believed that the sun does not rise in Moscow but in Rome. Years later, with Hitler in power, Codreanu reiterated this sentiment, emphasizing the Legion's alignment with the Nazi regime.

“I am against the policies of the great western democracies. I am against the little entente and the Balkan Alliance. I have not the slightest confidence in the League of Nations. I am with the countries of National revolution. Forty-eight hours after the victory of the Legionary Movement, Romania will be allied with Rome and Berlin, thus entering the line of its historical world mission -- the defense of the cross, of Christian culture and civilization.”

— Corneliu Codreanu

During a meeting with Julius Evola, in his parting words, Codreanu told him:

“Whether you are headed for Rome or Berlin, let all those who are fighting for our ideals know that the Iron Guard is unconditionally on their side in the unrelenting struggle against democracy, Communism, and Judaism.”

— Corneliu Codreanu

However, despite the Legion's understanding of the transnational struggle they were engaged in, they rarely devoted time or resources to foreign affairs. This is not surprising, considering the numerous challenges they faced within Romania, particularly financial difficulties.

Nevertheless, there were a few notable exceptions. One such instance was when the Legion sent Ion Mota as their representative to the 1934 Fascist conference in Montreux, Switzerland. This conference, hosted by Mussolini's CAUR (Action Committees for the Universality of Rome), aimed to establish a Fascist Internationale as a counter to the Communist International and to define the concept of "Universal Fascism."

The Communist International, under Stalin's influence, had a presence near the Romanian border. However, the Romanian Communist party was relatively small, with a membership that never exceeded 2,000 individuals, and ethnic Romanians constituted a minority within the party. Moreover, the party had been outlawed and supported Hungarian and Soviet territorial claims on Romanian land, which were highly unpopular positions.

At the Montreux conference, representatives from 13 countries, representing various fascist and third positionist movements, were in attendance. Notably absent were representatives from the NSDAP, which had come to power in Germany a year earlier. The official reason given was that the National Socialists had already attained state power. Nevertheless, it was impossible to ignore the strained relationship between Germany and Italy at the time, particularly concerning the issue of Austria. While the Italian government hosted the event, even representatives from the Italian fascist party were absent, as Mussolini wanted to observe the conference without their participation.

During the conference, Mota consistently emphasized the significance of addressing the Jewish question, much to the discontent of several other delegates, including Eoin O'Duffy of the Irish Blue shirts.

Ion Mota

Mota proclaimed:

“The problem at hand, that of building a new unity, especially concerns me. It is going to be necessary to do the impossible so that the fascist world of tomorrow is not divided into several blocs fighting one another. The problem of the Universality of Rome must concern us first of all. We must push ourselves to mutual common ground upon which we will be able to proceed tomorrow. As the Congress President has already said, we can only hope for one thing: that the fascist world of tomorrow forms a whole, from every point of view. We must not set ourselves too grandiose objectives, but we must recognize that each people has the right to settle its own peculiar problems, into which no one has the right to intrude. However, from another perspective, it is quite right that, on the great international questions, we should remain united so as not to compromise the fascist unity of tomorrow.

One is the actual existence of several bodies studying problems common to nationalist movements. These centres of study and activity would have to agree amongst themselves at the first opportunity. Furthermore, they would have to be invited to take part in future meetings of the "Committees". The second question concerns one of the main factors in the building of a unique, European and world bloc. This factor is that no major international problem must be ignored or left to one side. And, amongst these problems there is the Jewish Question, which is very serious for some countries and especially so for Romania.”

— Ion Mota

In a further controversial move, Mota insisted that the German National Socialists be invited to future conferences, emphasizing that the Jewish question could only be resolved through collaboration between the Italian fascists and the German National Socialists.

Another significant intellectual figure in the Legion was Vasile Marin, who firmly distanced the Legion from bourgeois conservatism.

“The Legion promotes the creative spirit in all the fields of public life and sincerely rejects conservatism. The Legion organizes the conquest of the future with the help of all the productive categories of the nation and does not represent a reaction toward the past… Like the Fascists and the National Socialists, we are closer to what is called the ‘Left’ than to what is called the ‘Right.’”

— Vasile Marin

Furthermore, Marin staunchly advocated for the establishment of a totalitarian fascist corporatist state. Using ideas influenced by Spengler, he contended that Romania needed a strong state in order to make its mark in history. Marin's anti-Semitism was not rooted in reactionary Christianity; instead, it was driven by ideology. Drawing inspiration from thinkers like Chamberlain, Wagner, and Nietzsche, he criticized Jews for their materialism, which contradicted the spiritual and idealistic vision of the totalitarian state he envisioned. According to Marin, the fundamental obstacle posed by Jews was their hindrance to Romania's mastery of modernity and entry into historical significance.

Codreanu also argued for a religious foundation for corporatism, rejecting the notion of a false dichotomy between faith and politics. He emphasized the concept of ecumenism at the core of the Iron Guard, perceiving it as a means of viewing society as a unified and living entity, fostering coexistence not only among the living but also with the deceased and God.

In their pursuit of revolutionary ideals, Mota criticized conservatism, highlighting the disparities between their former teacher, leader, and mentor AC Cuza. Mota condemned Cuza's belief that religion, culture, and nationality were merely symptoms of the national economy, deeming it a bourgeois materialistic perspective. This juxtaposed with the religious immaterialism of the Legion, and Mota explained that this philosophical divide between Cuza and the Legion was the reason for Cuza's lack of alignment with the Legion's emphasis on morality.

Expanding on the Legion's critique of conservatism, Marin envisioned the Legion not as a preserver of the old aristocracy but as creators of a new "aristocracy of deed." This new Legionary elite would establish a faith rooted in Christian Orthodoxy, which Marin saw as an expression of the Romanian people. This envisioned faith would unite the Romanian population into an organic and collective entity. In describing Marin's perspective on the peasantry, Mircea Platon writes:

“Like the rest of the population, Romania’s villagers were treated by Marin as a kind of raw material – a dark, anonymous human soil that had to be molded and propelled into History by the Iron Guardist ‘elite of the pure and intransigent ones.’ Marin placed all of his hopes on the ‘elite of our generation, the few, the chosen, the stubborn and the united,’ who would be capable of making the ‘crowds’ adhere to the national revolution.”

— Mircea Platon

Although the Legion acknowledged their alignment with other transnational political movements and their participation in a broader struggle, they consistently emphasized the distinctiveness of their own movement.

“In the [Italian] Fascist movement it is the state element that prevails, coinciding with organised force. What finds expression here is the shaping power of ancient Rome, that master of law and political organisation, the purest heirs to which are the Italians. National Socialism emphasises what is connected to vital forces: race, racial instinct, and the ethical and national element. The Romanian Legionary movement instead chiefly stresses what in a living organism corresponds to the soul: the spiritual and religious aspect.”

— Corneliu Codreanu

Despite their differences with the National Socialists regarding the emphasis on race, the Legion still held a concept of race. Ion Mota expressed his own racial beliefs in a letter, stating, "I confess, I am a racist, with some qualifications, including the fact that religion is not based on racial specificity..." Legionary writings and propaganda often glorified the pre-Christian Dacian and Thracian peoples, considering themselves proud descendants. While acknowledging the existence of racial differences and the biological variations among certain groups, the Legion did not develop a comprehensive genetic and biological "Romanianism" as the early National Socialist thinkers had done with "Nordicism," as exemplified by Houston Stewart Chamberlain.

Instead, the Legion primarily focused on the racial distinction between Jews and non-Jews. Non-Jewish Christians who assimilated into Romanian society and demonstrated loyalty to the state were accepted as Romanians. Over time, the Legion's stance on Jews began to soften, and official publications even suggested the possibility of assimilated and converted Jews being part of a Legionary state.

Ultimately, the Legion aimed to create a New Romanian individual who transcended materialism and embraced a sense of ontological Romanianness and Spiritual Christianity. As observed by a contemporary Italian observer:

“Above all, one thing should be very clear to everyone: The Legion of the Archangel Michael is not a party as we understand it, nor a pressure group, nor a para-religious organization, nor in any way denominational. It is an absolutely original movement whose primary goal and purpose are: a spiritual and moral renewal, and the creation of a new individual -- an individual who will stand in contrast to the democratic homo œconomicus, who is essentially pragmatic and egotistical.”

—

King Carol II and Continued Growth

During the time of the constitutional monarchy in Romania, King Carol II gradually amassed power and consolidated it within the monarchy. However, he had a controversial background that provided ample ammunition for his opponents. Prior to ascending the throne in 1930, he had been divorced twice and was involved in a scandalous affair with a Jewish woman named Magda Lupescu. In fact, he had previously relinquished his right to the throne in 1925 due to his personal life, resulting in his young son, Michael, becoming the King of Romania under a regency. This left Romania under the rule of an unremarkable regency.

Nevertheless, with the support of allies from the Romanian political elite, Carol II managed to reclaim the throne in 1930 through what can be described as a "soft" coup d'état. He then actively engaged in Romanian politics, providing financial support to political parties and exerting his monarchical powers, leading Romania down an increasingly authoritarian trajectory.

King Carol and his mistress

As Carol II's power grew, political parties in Romania started aligning themselves as either pro or anti-Carol, causing divisions within established political parties. In this political climate, opportunistic politicians began adopting increasingly authoritarian stances to capitalize on the changing tide, influenced by both the Monarch and radical parties like the Legion.

During this period, Professor Cuza joined forces with the anti-Semitic Romanian poet and politician Octavian Goga, forming a new party called the National Christian party to counter the Iron Guard. Ironically, they adopted tactics that Cuza had previously rejected, which had originally caused a split between Codreanu and Cuza. The new "blueshirts" of Cuza and Goga even clashed with Codreanu's "greenshirts" on the streets.

The Legion's popularity is further evidenced by the opportunistic move of the king, who created a carbon copy of the Legion through his Romanian Front party. This party, like Cuza's, emulated the Legion's salutes, mannerisms, youth groups, work camps, paramilitarism, and ideology. However, both parties remained mere imitations, lacking grassroots support and unable to replicate the dedication and fanaticism present in the Legionaries.

The Legion continued to expand, establishing more nests throughout Romania, recruiting members from various backgrounds, and establishing businesses. Their popularity grew, and even where they lacked in numbers, they compensated with unwavering dedication and fanaticism.

In 1934, a plot to kill Codreanu was uncovered, involving a prominent leader within the movement named Mihail Stelescu. Stelescu was promptly expelled from the Legion and formed his own organization called the "Crusade for Romania," also known as "the White Eagles." He managed to bring several high-ranking members over to his new group.

The split between Codreanu and Stelescu did not arise from ideological differences, but rather from Stelescu's desire for more power within the organization and his disillusionment with what he perceived as a lack of emphasis on politics. The Crusade for Romania quickly became a tool for the elites, as the king and others opposed to the Legion financed it in an attempt to divide the Legion. Stelescu spent much of his time attacking the Legion and specifically targeting Codreanu, even stooping so low as to question his Romanian identity and leadership capabilities. Stelescu eventually formed an alliance with Cuza. However, two years after Stelescu's expulsion, Codreanu, who had given him an opportunity to redeem himself, ordered his assassination. Several Legionaries, many of whom had personal connections with Stelescu, entered his hospital room and shot him. Stelescu's splinter group dissolved shortly after.

Death Squad responsible for killing Stelescu

The Martyrs