Russian National Unity: The Twilight of Soviet Collapse

by Orthodox Nationalist and Zoltanous

In the smoldering ruins of the Soviet colossus, as the iron grip of communism loosened and the once-mighty union fractured into a mosaic of humiliated republics, a fierce and unyielding force arose to reclaim the soul of Russia. This was Russian National Unity (RNU), a vanguard of militant nationalists who fused the ancient mysticism of Orthodox Christianity with National Socialism, all wrapped in the banner of irredentist fervor. Founded on October 16, 1990, by the indomitable Alexander Petrovich Barkashov and his steadfast associate Viktor Mikhailovich Yakushev, RNU was no mere political party but a revolutionary movement, an All-Russian Orthodox National-Socialist crusade aimed at purging the motherland of alien corruptions and restoring a divine empire where Russians stood as the chosen bearers of God’s will. Born from the economic despair, social chaos, and national shame of perestroika’s fallout, it channeled the rage of the dispossessed into paramilitary drills, vigilante patrols, and a metaphysical worldview that saw the world as a cosmic battlefield between holy order and satanic disorder. At its zenith in the mid-1990s, RNU commanded up to 25,000 dedicated followers across Russia’s vast expanse, with tendrils extending into the Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, as well as Ukraine, operating as an unregistered fascist entity that dreamed not just of revival but of a total reclamation of “Holy Rus’.” Its members, clad in black shirts symbolizing renunciation and readiness for martyrdom, swore oaths of “Russia or Death!” and positioned themselves as the nation’s last line of defense against internal decay and external subversion, drawing from the deep wells of Slavic tradition and the unyielding spirit of historical warriors who had once repelled invaders from the steppes.

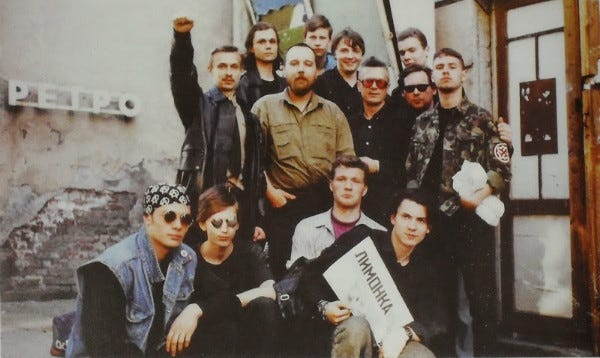

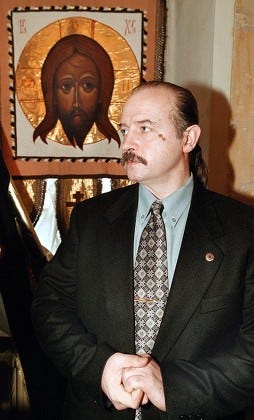

Photos of RNU

The origins of this formidable organization trace back to the nationalist underground of the late 1980s, where Alexander Barkashov emerged as a figure of raw determination and ideological clarity, a man forged in the crucible of Soviet conformity yet destined to shatter it. Born on October 6, 1953, in Moscow to a modest working-class family — his father a simple laborer toiling in the factories that powered the regime, his mother a homemaker nurturing the home front amid the drab uniformity of communal living — Barkashov grew up in the shadow of an empire that promised equality but delivered stagnation, harboring a restless spirit that propelled him beyond the mundane drudgery of everyday existence. A trained electrician by trade, he served in the Soviet army as a commando, honing skills in hand-to-hand combat, marksmanship, and tactical maneuvers, while earning a black belt in karate that would later become a cornerstone of RNU’s rigorous physical training regimen, instilling in recruits the discipline of body and mind essential for the coming struggle. By 1985, disillusioned with the atheistic materialism of the regime and the hollow promises of glasnost, Barkashov immersed himself in the burgeoning nationalist scene, joining the National Patriotic Front “Pamyat’” (Memory) as second-in-command under the charismatic but erratic Dmitri Vasilyev, a group that railed against perceived Jewish influences and sought to revive Russian cultural pride through fiery rallies and historical reenactments.

“The aim of international Zionism is to seize power worldwide. For this reason Zionism struggles against national and religious traditions of other nations, and for this purpose they devised the Freemasonic concept of cosmopolitanism.”

— Dmitri Vasilyev, letter to Russian President Boris Yeltsin, published in the newspaper Russkoye Voskreseniye 1993

Pamyat, with its theatrical parades in Cossack uniforms, its revival of Black Hundreds ideology, and its openly anti-Semitic rhetoric, initially served Barkashov’s ambitions. He soon grew frustrated, however, with the organization’s chronic lack of discipline, its preference for flamboyant spectacle over serious political work, and its inability to build a disciplined, militant cadre capable of contending for real power.

A photo of Dmitri Vasilyev

Various photos of Alexander Barkashov

In a revealing 1993 interview on the television program 600 Seconds with journalist Alexander Ilyin, Barkashov candidly admitted that he had infiltrated Pamyat’ primarily to recruit like-minded souls for his own vision, a move that sparked debates among observers about whether his drive was purely ideological, rooted in a profound love for the Russian ethnos, or laced with personal ambition for unchallenged leadership in the nationalist pantheon. Alongside him in those formative days was Viktor Mikhailovich Yakushev, a shadowy but crucial figure who handled early administrative tasks, rallying supporters through underground networks and organizing the initial “Slavonic and Russian sobors” — grand assemblies that drew crowds of disaffected youth, battle-hardened veterans from the Afghan quagmire, and intellectuals weary of the liberal reforms that seemed to erode the very foundations of Russian identity. Though Yakushev’s role diminished over time, fading into the background as Barkashov’s commanding presence took center stage, their partnership laid the foundation for RNU’s hierarchical structure: Barkashov as the supreme vozhd (leader), commanding absolute obedience from regional commanders and a central council that enforced ironclad loyalty through oaths, rituals, and the threat of expulsion for any hint of deviation.

As RNU coalesced into a coherent force, it swiftly outpaced the splintering remnants of Pamyat’, becoming the defining embodiment of nationalism in the early 1990s, a period marked by hyperinflation, rampant crime, and the sell-off of state assets to oligarchs that left millions in destitution. Barkashov, drawing from his military background and the lessons of historical movements, molded the group into a disciplined paramilitary machine, complete with its own elite wing known as the Russian Vityazi (Russian Knights) — sometimes evocatively called “Bogatyrs” after the legendary Slavic warriors of folklore who embodied superhuman strength and unyielding defense of the homeland. These units underwent rigorous training in small arms handling, explosives fabrication and deployment, urban combat tactics, wilderness survival skills, and even psychological conditioning to withstand interrogation, often conducted in secluded forest camps where recruits forged bonds of brotherhood amid the harsh Russian winters. By mid-1993, RNU had established branches nationwide, from the frozen tundras of Siberia to the bustling, decaying streets of St. Petersburg, positioning itself as a “reserve force” ready to defend Russia against perceived threats from within — such as migrant influxes from the Caucasus and Central Asia and without, including the encroaching influence of NATO and Western liberalism. The group’s rapid growth was fueled by the era’s economic cataclysm, with Barkashov masterfully exploiting recruitment drives that targeted alienated young men from crumbling industrial towns, promising them not just purpose but a sacred role in the resurrection of Russian greatness, through pamphlets, underground videos, and word-of-mouth networks that evaded the watchful eyes of the FSB’s predecessors.

Photos of RNU

Yet it was the 1993 Russian constitutional crisis that catapulted RNE to its historical apex, a moment of raw confrontation that nearly mirrored Mussolini’s March on Rome in its potential for transformative upheaval, etching the group’s name into the annals of post-Soviet rebellion. As tensions boiled over between President Boris Yeltsin, whose market reforms had plunged the nation into poverty, and the Supreme Soviet, which sought to curb his powers, RNU mobilized a 150-strong contingent — later swelling to around 300 with impromptu volunteers from sympathetic nationalists to defend Moscow’s White House against Yeltsin’s forces, transforming the parliamentary building into a fortress of defiance. Acting on direct orders from Supreme Soviet President Alexander Rutskoi, they seized City Hall in a bold, coordinated assault, their black-shirted fighters displaying remarkable discipline amid the swirling chaos of barricades, gunfire, and tear gas, while communists, monarchists, and eccentrics milled about in disorganized chaos. Barkashov himself served as an aide to Defense Minister Vladislav Achalov, maintaining shadowy ties to both sides of the conflict, as he later revealed in a 2013 interview where he boasted of strategic maneuvering to safeguard the movement’s survival amid the betrayal and confusion. Promises of official paramilitary status dangled before them if the uprising succeeded, envisioning RNU as a sanctioned guardian of the state, but Yeltsin’s tanks crushed the rebellion on October 3-4, 1993, shelling the White House in a barrage that left the structure ablaze and bodies strewn across the pavement, leading to heavy casualties among RNU ranks — some killed in the crossfire, others summarily executed or forced into desperate emigration to avoid reprisals. Barkashov went into hiding, evading capture for weeks in a network of safe houses before his eventual arrest, and the group faced a temporary nationwide ban that sought to erase its existence from the public sphere. Yet, in a twist of fate that underscored the fragility of Yeltsin’s grip, a 1994 amnesty not only freed him but invigorated recruitment, as the “martyrs of the White House” became legends in nationalist lore, their sacrifice immortalized in songs, graffiti, and clandestine memorials that fueled a surge in membership. Barkashov reflected on this event in the pages of RNU’s newspaper Russian Order that year, capturing the essence of their resolve amid the betrayal of establishment politicians.

“By the middle of 1993, the Russian National Unity actually became an All-Russian organization… Russian National Unity did not come to the Supreme Soviet or the ‘White House’, we came to Our Field of Honor… We have come out against the very enemy who has long been trying to destroy Our Fatherland with the wrong hands. And we were not ‘pawns in someone else’s game’—we knew where and why we were going. Unlike the Zyuganovs and Zhirinovskys, we could not stand aside—Russian Honor leaves no choice!”

— Alexander Barkashov, Russian Order newspaper, 1993

At the heart of RNU’s enduring appeal lay its intricate ideology, a potent synthesis of fascist traditions, Orthodox mysticism, and Russian exceptionalism that Barkashov articulated in seminal works like Azbuka Russkogo Natsionalista (ABC of The Russian Nationalist), texts that served as bibles for recruits and blueprints for the envisioned society. Drawing heavily from the 1930s-1940s All-Russian Fascist Party of Konstantin Rodzaevsky — a White émigré who operated from the exile haven of Harbin in Manchuria, collaborating with Japanese imperial forces and Nazi Germany before his capture and execution in 1946 — RNU embraced “Russian fascism” as a bulwark against Bolshevism’s remnants, infused with virulent anti-Semitic and anti-communist zeal that viewed the Soviet era as a Jewish-orchestrated aberration. Rodzaevsky’s writings, smuggled back into Russia during the ideological thaw of perestroika, provided a blueprint for expelling “alien elements” and building a corporatist state where labor and capital served the nation, but Barkashov elevated this framework with a unique “Mystical Nationalism” that framed history as a divine struggle between cosmic forces, Russians as the God-bearing people destined to lead the final crusade against the anti-christ. He articulated this metaphysical dualism with profound clarity, positioning the Russian ethnos at the center of a spiritual war that transcended mere politics.

“The highest, metaphysical, absolute Goodness is God; its manifestations are naturalness, regularity, order, supreme justice. Metaphysical, absolute evil is the devil; its manifestations are artificiality, lawlessness, chaos… The Russian People are the God-bearing People (that is, those who carry God within themselves).”

— Alexander Barkashov, ABC of The Russian Nationalist

In this cosmology, Russians were the builders of a just empire called “Holy Rus’,” a sacred realm contrasting the “God-fighters” of Israel — a thinly veiled anti-Semitic view deriving from the Hebrew etymology meaning “wrestles with God” — or the materialistic West led by a U.S.-dominated “new world order” bent on eroding national sovereignty through liberal globalization and cultural homogenization. This evil, Barkashov argued, infiltrated through philosophy, degenerating into outright Satanism and the creation of a “gray race” through miscegenation, but the Russian genotype offered innate resistance, a spiritual armor forged in the trials of history from the Mongol invasions to the Bolshevik terror. This dualism extended to global politics: The world was Christ’s arena against the anti-christ, with an “international financial oligarchy” — coded language for Jewish conspiracies, orchestrating chaos to enslave humanity. Regimes like Mussolini’s Italy, Franco’s Spain, Antonescu’s Romania, Hitler’s Germany, or Salazar’s Portugal were critiqued as mere materialists who attacked symptoms like corruption without uprooting the metaphysical rot, as seen in the failures of Pinochet’s Chile or even Tsarist figures like Borodin, whose efforts faltered for lacking divine insight. True victory demanded mystical elevation, with nations as eternal archetypes in a “last crusade” to crush a satanic Western civilization, branches of RNU forming under the blessing of the Catacomb Church, modeled on Ivan The Terrible’s Oprichnina — the feared secret police that purged traitors in the name of Pravoslaviye, Samoderzhaviye, I Narodnost (Orthodoxy, Autocracy, and Nationality).

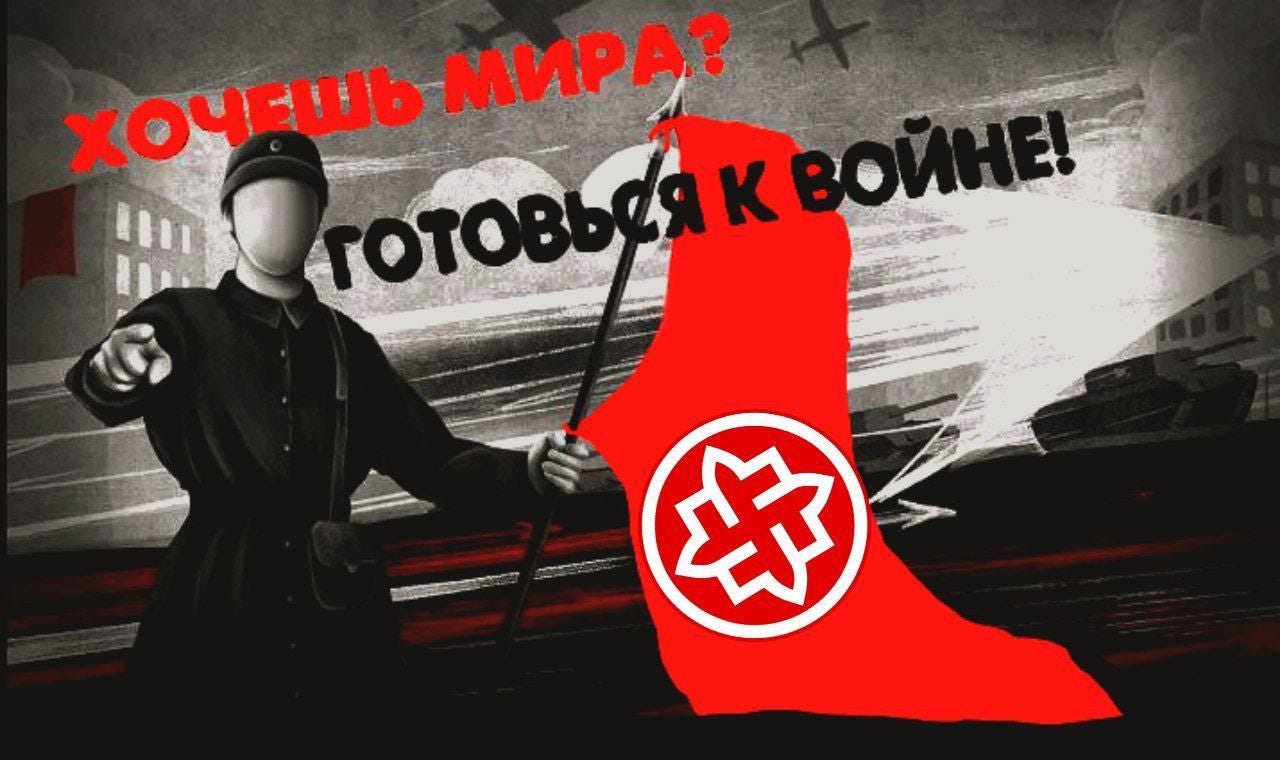

Flags used by RNU

An RNU recruitment poster

Influences abounded in shaping this worldview: Ivan Ilyin, the White émigré philosopher expelled from Soviet Russia in 1922 aboard the infamous “philosophers’ steamship,” whose monarchist authoritarianism and pro-fascist writings, praising Hitler’s early anti-Bolshevism as a defense of European civilization, echoed in Barkashov’s warnings against conflating the national Russia with the godless USSR, urging a separation of true patriotism from state idolatry. Ivan Ilyin’s collaborations with Nazi sympathizers in the Russian All-Military Union (ROVS), a White émigré organization that aided the Third Reich against the Soviets, resonated deeply, as did overt admiration for Hitler himself, whom Barkashov saw as a model for mobilizing a nation against degradation. In a 1994 interview with The Moscow Times, Barkashov declared his unapologetic esteem for the Führer, viewing him as a champion of racial purity and national revival.

“I consider [Hitler] a great hero of the German nation and of all white races. He succeeded in inspiring the entire nation to fight against degradation and the washing away of national values.”

— Alexander Barkashov, The Moscow Times, 1994

Affiliated with the World Union of National Socialists, RNU rejected the “Nazi” label publicly to evade legal scrutiny while celebrating Hitler’s tactics in private, advocating the expulsion of “non-Russians” without external homelands — Jews, South Caucasians, Central Asians, while tolerating indigenous minorities like Tatars or Bashkirs provided they assimilated into the Russian fold. Internal documents and discussions, however, hinted at darker intents, including the extermination of Jews and Gypsies as ultimate solutions to perceived threats, though such plans remained unfulfilled amid relentless state repression and the group’s focus on survival.

Photos of RNU

Far from the caricatured image of fascists as rabid free-marketeers, RNU’s economic doctrine was a fierce repudiation of Yeltsin’s shock therapy, advocating instead a rigidly state-directed system that preserved the commanding heights of the Soviet economy while purging it of “alien” (Jewish-Bolshevik) influences and redirecting it toward the ethnic Russian people. Privatization was decried not as inefficiency but as treasonous plunder, a deliberate handover of the people’s wealth to cosmopolitan oligarchs who had orchestrated the USSR’s downfall to enslave the survivors. In the foundational 1993 Declaration of Russian National Unity — reaffirmed and expanded at the 1997 founding congress as the core platform, RNE demanded the immediate nationalization of all strategically important branches of industry, transport, energy, and banking, insisting that “the land and subsoil of Russia are the inalienable property of the Russian people” and must be shielded from foreign or private predation. This was no mere nostalgia for Stalin’s five-year plans; it was a vision of “national socialism with Russian characteristics,” where the state’s iron grip on production ensured full employment and social welfare — but only for the God-bearing nation, excluding “non-indigenous” migrants and minorities slated for expulsion.

Barkashov, ever the vozhd of disciplined fury, hammered this point in interviews and tracts, framing the market reforms as a “Zionist plot” to atomize and impoverish Russians while enriching a parasitic elite. Barkashov denounced the so-called ‘reforms’ are nothing but the robbery of the Russian people by international capitalism. He vowed that RNU would “return all stolen property to the state” through a sweeping audit of privatizations since 1991, confiscating assets from “traitors and aliens” without quarter. Small-scale private enterprise might survive if owned by loyal ethnic Russians — artisans, farmers, shopkeepers — but only under corporatist syndicates subordinated to national goals. The RNU voiced strong moralism against “usurious” finance capital. Denouncing stock exchange capital and private Banking as the eternal Jewish spirit, it would be fully nationalized, with interest-bearing loans abolished as “Jewish exploitation,” replaced by state credit disbursed interest-free for “nationally vital” projects like arming the Vityazi or fortifying borders. Social guarantees — free healthcare, education, housing, pensions, were to be enshrined as sacred duties of the state via the constitution, expanded even beyond Soviet levels, but gated behind blood and soil. Only the Russian people and loyal indigenous folk would be able to partake in this, as the 1997 platform stipulated, with non-Russians remitting wealth abroad or facing deportation to their true homelands.

This program, laid bare and circulated widely in 1997, it positioned the movement as the avenger of the 1990s’ “great theft,” where factories forged in Russian sweat were auctioned to Berezovsky and Khodorkovsky for kopecks, leaving breadlines in their wake. Barkashov likened it to a “second October Revolution,” but inverted: not proletarian internationalism, but ethnic autarky, withdrawing Russia from global trade pacts to pursue self-sufficiency in grain, steel, and souls. Autarky meant capital controls, import bans on “degenerate” Western goods, and a fortress economy geared for the “last crusade” against cosmopolitan decay. It was this material radicalism — closer to the KPRF’s nostalgia than Zhirinovsky’s carnival, that forged RNU’s “Red-Brown” bonds, allowing black-shirted Knights to stand with red-bannered workers against Yeltsin’s tanks, their shared hatred of the oligarchs a bridge over the ideological abyss.

One struggle against Yeltsin in action

RNU with a veteran of the Great Patriotic War

White House Black Smoke (Announcement) on Russian National Unity

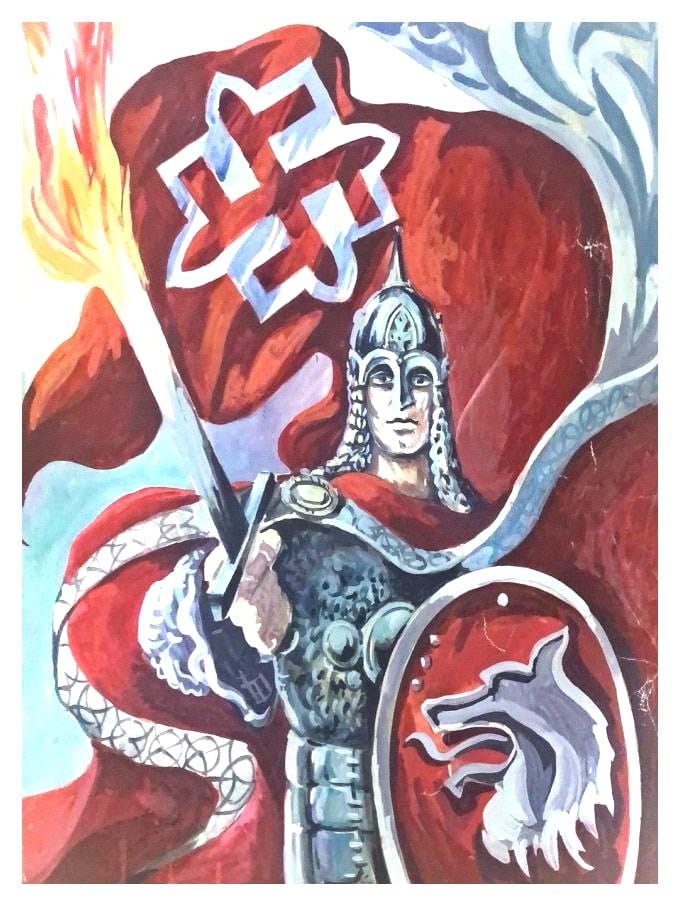

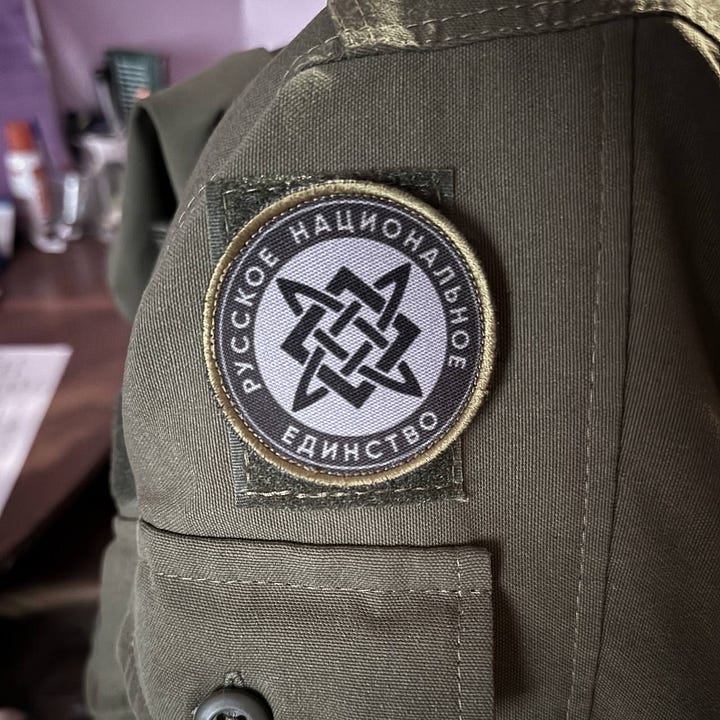

Symbolism permeated every aspect of RNU’s culture, reinforcing its paramilitary ethos and mystical underpinnings, creating a visual and ritualistic language that bound members in a shared identity. The stylized Kolovrat swastika, an ancient Slavic sun wheel representing eternal renewal and the cycle of life, adorned flags, uniforms, and tattoos in maroon hues evoking the blood of martyrs and the sacred soil of the motherland, emblazoned with the uncompromising slogan “Russia for Russians.” Black shirts harkened back to the warrior-monks of the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380, who donned dark robes in solemn preparation for death against the Mongol hordes, symbolizing renunciation of worldly comforts in favor of eternal struggle. Ranks structured the hierarchy with military precision — supporters at the base providing logistical aid, rising to co-workers who handled propaganda and recruitment, and culminating in elite comrades-in-arms who formed the vanguard in combat operations — while the newspaper Russian Order disseminated ideological tracts, calls to action, and exposes on “alien influences,” reaching thousands through samizdat distribution networks that defied censorship. Activities ranged from indoctrination in “military-patriotic clubs” for youth, where recruits learned history through a nationalist lens that glorified figures like Ivan the Terrible and demonized Lenin as a foreign agent, to outright vigilantism that blurred the lines between defense and aggression. RNU units patrolled neighborhoods plagued by crime, clashing with perceived criminals — often migrants from the Caucasus or Central Asia, in acts of “volunteer justice” that included brutal beatings, targeted murders, and desecrations of graves in regions like Tver, where synagogues and mosques became focal points of symbolic attacks. They cooperated sporadically with the FSB in anti-crime operations, blurring the boundaries between state and shadow forces in a pragmatic alliance against common foes, but unleashed terror independently: assaults on ethnic minorities, distribution of hate literature through leaflets and early internet forums, and even fielding candidates in the 1998-99 elections before widespread bans curtailed their political ambitions. A 1995 incident exemplified the regime’s ambivalent repression — operatives linked to the Presidential Security Service coerced Barkashov into a humiliating videotaped apology to Jews and Blacks, circulated to discredit him and sow division, yet that same year, a major conference in Moscow drew 304 delegates from 37 regions, showcasing the group’s resilience and ability to mobilize despite constant harassment.

RNU edit

The post-1993 era brought waves of repression that chipped away at RNE’s foundations, a relentless campaign by the Yeltsin administration and its successors to dismantle the organization through legal, extralegal, and violent means. In 1998, Moscow Mayor Yuri Luzhkov banned a second national conference, citing public order concerns amid fears of mass rallies; 1999 saw electoral exclusion from the Spas bloc and a citywide prohibition that forced operations underground. Regional crackdowns followed like a domino effect — Omsk in 2002, Tatarstan in 2003, Ryazan in 2008 — amid a litany of arrests, show trials, and violent confrontations that claimed lives on both sides. A particularly brutal episode unfolded on May 9, 2005, when SOBR special forces ambushed rally participants commemorating Victory Day, imprisoning Moscow leader Dmitry Maslov (who later succumbed to tuberculosis after his release, a death many attributed to prison conditions), vandalizing headquarters with graffiti and destruction, and jailing Barkashov for two years on fabricated weapons charges that highlighted the state’s willingness to bend the law. Internal fractures accelerated the decline: By 2000, disputes over strategy, whether to pursue revolutionary purity through armed insurrection or pragmatic alliances with the state and Barkashov’s increasingly authoritarian style, which brooked no dissent, led to a major split that fragmented the once-unified structure. Factions like Barkashov’s Guard emerged as loyalist holdouts, while others went independent, dissolving the federal apparatus and rendering the official website defunct by 2006, though underground cells persisted illegally in remote areas, echoing Ilyin’s prescient warnings about nationalists conflating “our state” with the regime, a pitfall that also plagued contemporaries like Eduard Limonov’s National Bolshevik party (NBP) in their quixotic quests for relevance.

RNU’s entanglement with the broader currents of post-Soviet “Red-Brownism” — the uneasy fusion of nationalist “brown” fascism and communist “red” ideology — further illuminated its role in the chaotic 1990s opposition, where ideological boundaries blurred in the face of shared enmity toward Yeltsin’s liberal oligarchy. As the Soviet collapse unleashed economic shock therapy that enriched a few while impoverishing the masses, RNU found itself allied with unlikely bedfellows in the National Salvation Front, a coalition that included communists like Gennady Zyuganov’s KPRF, nationalists, and even elements of Limonov’s NBP, all united in their rejection of Western-imposed capitalism. Barkashov, alongside ex-General Vladislav Achalov, co-founded the Union of Defenders of Russia in 1993 amid the constitutional crisis, positioning RNU’s black-shirted storm troopers as frontline defenders in the White House standoff, where they smuggled in weapons and held positions against Yeltsin’s assault. The siege ended in bloodshed, with tanks shelling the building and hundreds killed; Barkashov narrowly escaped, only to be shot by an unknown assailant later, arrested, and briefly imprisoned before the 1994 amnesty allowed him to parade openly once more.

“Yeltsin, appearing on television early yesterday morning, assailed the actions of what he called a ``fascist-communist rebellion.’‘ He portrayed the government as unprepared for their well-organized violence, a claim for which there was evidence in the panicked retreat of police forces in the face of anti-Yeltsin demonstrators Sunday afternoon.”

— Daniel Sneider, Yeltsin Prevails, Military Crushes Parliament Forces

“Sensing that the long-awaited civil war was about to begin, Limonov and his supporters flocked to the parliament building. They were joined by thousands of Red-Brown extremists, including Barkashov’s black-shirted storm troopers who brought their weapons with them, expecting a fight.”

— Martin A. Lee, The Beast Reawakens

RNU in the chaos

Photos of RNU

Limonov and Dugin with Russian National Unity and National Bolsheviks in the 90s

RNU’s immortal regiment

Post-crisis, RNU expanded dramatically, reaching 64 regions by 1998 and operating boot camps for fascist indoctrination, where youth were drilled in ideology and combat, often with tacit leniency from authorities wary of alienating nationalist sentiments. Barkashov attempted a reinvention as a “serious politician” in 1995, but Limonov critiqued his overt Nazism as impractical for broader alliances, highlighting tensions within the Red-Brown spectrum where RNU’s mystical Orthodoxy clashed with NBP’s punkish anarcho-fascism. Nonetheless, RNE penetrated deeper into nationalist circles, its newspaper Dyen publishing excerpts from various fascist thinkers, and its members forming the backbone of vigilante groups that targeted minorities in a bid to “cleanse” Russia.

Art made by the RNU

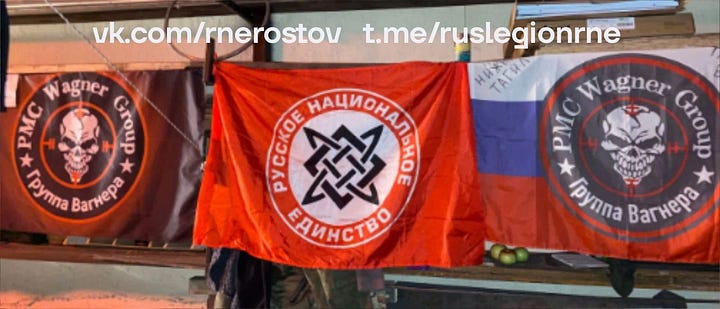

Yet RNU’s legacy endures far beyond its formal dissolution, a fractured but potent shadow in Russia’s ongoing geopolitical struggles, particularly in the Russian-Ukrainian war where its ideological embers have ignited new flames. Deviation from its original zeal invited infiltration by state agents and internal decay, but ex-members seeded nationalist activism across the spectrum, from street-level skinhead gangs to intellectual circles influenced by Alexander Dugin’s Eurasianism. During the Western backed 2014 Maidan coup, Barkashov denounced the uprising as a Western-orchestrated plot against Slavic unity, aligning with pro-Russian separatists in a continuation of RNE’s irredentist dreams. A leaked phone call in May 2014 captured him advising Donetsk militant Dmitry Boitsov on rigging a referendum for the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR), suggesting an inflated 89% “yes” vote to legitimize secession and carve out a Russian enclave. RNU veterans flocked to the Donbas front lines, forming units like the Russian Orthodox Army — a direct successor group that blended Orthodox iconography with Nazi symbols in brutal campaigns against Ukrainian forces, establishing an office in Donetsk and wielding early influence in the DPR’s chaotic formation. Affiliates such as the Rusich, the Russian Imperial Movement, and even elements of the Wagner Group — infamous for their mercenary operations, carried RNU’s banner into the fray, supporting Russian operations. Pavel Gubarev, a former RNE member, rose to head the DPR, embodying the group’s penetration into separatist leadership. However, power struggles soon marginalized the nationalists: By late 2014, pro-Russian communists and moderates, including affiliates of the Communist party of the Russian Federation, consolidated control through sham elections and purges, effectively “voting out” RNU hardliners in a betrayal similar to the 1993 fractures.

RNU volunteer units in the Russian-Ukrainian war

Volunteer detachments of the RNU video

The emblems of SMO fascists fighters: Russian All-Military Union, Rusich, Varangian” Detachment, Imperial Legion, Legion of Saint Stephen, and Russian National Unity

From afar in Russia, Barkashov voiced unwavering support for the 2022 full-scale invasion, declaring readiness to combat “Banderites” — a derogatory term for Ukrainian nationalists invoking the legacy of Stepan Bandera and fragments of RNE continued recruiting for the front lines until at least 2025, aligning with Vladimir Putin’s narrative of “historical unity” that denies Ukrainian sovereignty as a fabricated division imposed by external forces like NATO. These militants, scattered among Wagner offshoots and other irregulars, carry forward RNU’s mystic ethno-nationalism, influencing today’s militias in a war that echoes the group’s foundational battles against perceived existential threats, from the White House siege to the trenches of Donbas. Even as RNU formally disbanded, its fragmented members remain active, with Barkashov himself staying influential in underground nationalist circles, contributing fighters to the ongoing conflict and perpetuating the Red-Brown synthesis that sees Russia as the bulwark against globalism.

In retrospect, RNU’s rise and fall encapsulate the tragic arc of post-Soviet nationalism: a blaze of righteous fury ignited by imperial collapse, tempered in the fires of rebellion, and ultimately smothered by internal rot, state co-optation, and the inexorable march of geopolitical realignments. What began as a pure vision of divine restoration, blending Orthodox mysticism with fascist discipline, devolved into splintered factionalism amid alliances with communists and separatists, yet its ideological embers continue to flicker in Russia’s undercurrents — a reminder that the quest for “Holy Rus’” persists amid the shadows of empire. Barkashov’s movement may have faded into illegality, but its spirit, like the eternal Kolovrat sun, refuses to set entirely, casting long shadows over the battles yet to come, where Red and Brown converge in the defense of a besieged Russian civilization. RNU can only really be compared to the fanaticism of the Romanian Iron Guard here. If anyone thinks that RNU has fully disappeared, they are very much mistaken.

RNU soldiers in Sumy, 2025

“The Russian National Unity considers the Nation not as an object of ‘social salvation,’ but as the bearer of an archetype, potentially capable of joining the ranks of the Army of Christ for the final battle against world evil.”

— Alexander Barkashov, quote attributed to Alexander Barkashov

Special thanks to RNU: https://t.me/rnationalunity

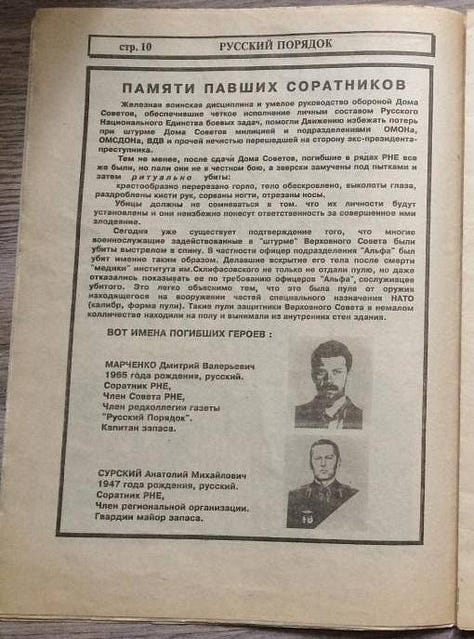

IN MEMORY OF THE RNU COMPANIONS WHO DIED IN OCTOBER ‘93

Comrades of the Russian National Unity who died defending the Supreme Soviet of Russia on October 4, 1993 in Moscow:

Marchenko Dmitry Valerievich, born in 1965, reserve captain S.A., comrade of the RNU since its foundation. He died on the evening of October 4, brutally beaten by the brutalized militants of Yeltsin-Chubais. According to eyewitnesses, he fought hand-to-hand to the end.

Sursky Anatoly Mikhailovich, born in 1947, guard major, participated in repelling the landing of two landing groups on the roof of the Supreme Soviet building, killed by a sniper.

We all remember the “gentlemen” liberals and other lovers of the West.

We all remember.

Remember, Lord, the warriors Dmitry and Anatoly in Thy Kingdom!