Introduction

The period following World War II has seen a proliferation of misinformation concerning the Third Reich, the National Socialist German Workers' party (NSDAP), and its key personalities. A significant portion of these inaccuracies and embellishments can be attributed to the efforts of intelligence agencies such as the OSS (the precursor to the CIA), the KGB, and the FBI. Moreover, individuals known for their deceptive practices have also played a role in shaping these narratives. Among them, Hermann Rauschning, a defector from the NSDAP to the United States in 1936, has been particularly active in disseminating negative propaganda against Adolf Hitler, the NSDAP, and the Third Reich's policies. This article will delve into the life of Otto Strasser, a figure who stands out as a scumbag within the National Socialist movement. Notoriously known for his acts of betrayal, to the extent that he was labeled a "political enemy" by his own brother, Gregor Strasser. Otto Strasser's story is a remarkable account of disloyalty, lies, and intrigue within the NSDAP.

The Divide: Hitler and Strasser

When discussing the concept of Strasserism is often depicted as a more radical, left-leaning faction within the Nazi party, seen by some as socialist adversaries to Hitler. This perspective is held by certain members of the Nazi party, some leftists, and a few historians, suggesting Strasserism offered a more "anti-capitalist" flavor of Nazi ideology. However, it's crucial to address the real differences between Hitler and Otto Strasser, specifically concerning the misperception that Hitler lacked socialist tendencies while Otto embodied them. In reality, Hitler was drawn to the Nazi Party in 1919, influenced by Gottfried Feder, a Nazi economist known for his socialist leanings and the author of the party's platform.

Historians, including Ian Kershaw, have illuminated an often-overlooked aspect of Adolf Hitler's early political activities, particularly his significant involvement with the communist Bavarian Soviet Republic. Contrary to the common depiction of Gregor Strasser as the left-wing element of the Nazi party, Hitler was deeply involved in communist activities. He not only took an active role within the Bavarian communist government but also worked closely with the Soviet Propaganda Department and held a position as a deputy battalion representative under Eisner's short-lived rule. This involvement is clearly illustrated by Hitler's attendance at the funeral of Kurt Eisner, a Jewish communist leader. This event was captured in photos by Heinrich Hoffmann and recorded on film on February 26, 1919, in Munich, providing strong evidence of Hitler's leanings towards communism.

Showcasing who was pro and anti-Soviet

Adolf Hitler attending the funeral

"Soon, other left-wing converts joined him in the party. One was Sepp Dietrich, a former head of the Soldiers’ Council of a military unit who would subsequently head Hitler’s personal guard unit—the Leibstandarte-SS ‘Adolf Hitler’—and would become a general in the Waffen-SS in the Second World War. Julius Schreck, another new DAP member, who would serve Hitler as driver and aide, had been a member of the Red Army during the days of the Munich Soviet Republic. Hitler was well aware of the past of many of the party’s new recruits. As Hitler would state on November 30, 1941, ‘Ninety percent of my party at the time was made up by leftists.’”

— Thomas Weber, Becoming Hitler: The Making of a Nazi

During a dinner gathering that included Otto Strasser, Adolf Hitler, and General Ludendorff, tensions arose between Otto and Hitler. Hitler criticized Otto for his involvement in suppressing the Kapp Putsch, leading to continued arguments until Ludendorff intervened and sided with Otto. However, disagreements persisted, particularly regarding war, Jews, and socialism. Hitler expressed his difficulty in getting along with Otto, whom he deemed an intellectual. After participating in the failed Beer Hall Putsch alongside Hitler, Gregor Strasser was briefly imprisoned but later sold his apothecary shop to fully dedicate himself to the Nazi party. He relocated to North Germany, where he quickly became a prominent figure in the Sturmabteilung (SA) and gained a significant following. Gregor was known for his strong socialist beliefs and commitment to "undiluted socialist principles."

In 1925, Otto joined the NSDAP. At that time, the party was disorganized due to the aftermath of the Beer Hall Putsch, which resulted in the arrest of many leaders and a temporary ban on the party. Otto joined the party's northern section led by his brother Gregor. Otto played a significant role as the editor and owner of the party's northern magazine, Arbeitsblatt. The magazine advocated for land redistribution, nationalization, strikes, agrarianism, anti-imperialism, class warfare, and a form of "democratic" National Socialism. Otto collaborated with Joseph Goebbels, an emerging figure in the Nazi Party who shared many of Otto's ideas. Together, they worked on a new program, known as the Strasser Program, which aimed to replace the original 25 points of the NSDAP, which they considered vague and outdated. They also sought to limit the leader's power. However, tensions arose as Hitler began to rebuild and consolidate control over the party. He shifted from a more socialist platform and violent revolution to a pragmatic and electoral approach, attempting to win the support of the nationalist bourgeoisie class. This led Hitler to reject the Strasser program, causing frustration and disappointment among the Strasser brothers and even Goebbels. Hitler claimed the program was too mild and lacked a "volkisch spirit," viewing it as a threat to his own authority within the party.

Gregor and Otto Strasser opposed Hitler's policy of seeking support from major industrialists. Their outspoken views created a deep divide with Hitler and other party leaders. In 1926, Gregor collaborated with his brother to establish the Berliner Arbeiter Zeitung, a nationalist newspaper that advocated for a global social revolution and expressed support for Lenin and the Bolshevik regime in the Soviet Union. Gregor was later elected to the Bavarian Legislature in the same year.

Louis L. Snyder has argued that Gregor initially wanted to overtake Hitler:

"In this capacity he proved to be an able organizer, an indefatigable if weak speaker, a shrewd politician, and a lover of action. Using his parliamentary immunity to protect him from libel suits and holding a free railway pass, he turned his energy to seeking the highest post in the National Socialist Party. He would push Hitler aside and replace him. Gregor Strasser regarded himself as a proud intellectual who had far more to offer the party than Hitler.”

— Louis L. Snyder, The Ideaological Origins of Nazi Imperialism

During the NSDAP annual conference on February 14, 1926, Gregor Strasser made a controversial statement advocating for the destruction of capitalism by any means necessary, including potential cooperation with the Bolsheviks in the Soviet Union. Joseph Goebbels supported Gregor's stance at the conference. However, Hitler argued that such a public position would be highly unpopular among the German masses. The majority ultimately sided with Hitler's viewpoint.

At times, Goebbels would draw comparisons between the Nazi movement and Lenin's Soviet Union, suggesting that the differences between National Socialism and Soviet Internationalism were minimal. These comments were published in works such as National Socialism or Bolshevism, An Open Letter to My Friends on The Left, and the National Socialist Letters of 1925. However, this approach quickly backfired as it triggered an anti-Nazi riot, with the media attacking the Nazis by branding them as communists. The Social Democratic Party (SPD) even labeled the Nazis as "right-wing Bolsheviks." Hitler had to intervene to calm the situation, which ultimately validated his concerns. As a result, Goebbels switched sides, and from that point on, Gregor referred to him as the "scheming dwarf." Furthermore, it is often mentioned that Hitler and the Strasser brothers held differing views on property relations. With these two quotes below for example, we can see why this was the case:

It is important to provide the proper context when discussing the distinction between Hitler and the Strasser brothers regarding property relations. While it is true that Hitler occasionally denied advocating for the nationalization of private property during elections, this should not be seen as a fundamental ideological difference.

Hitler said this:

The Strasser brothers, along with Hitler, voiced critiques of private property as a privileged institution. Gregor Strasser, together with Hitler and Otto, promoted a sophisticated stance that acknowledged the value of small-scale private property, highlighting its societal role and compatibility with national interests. They posited that production-related property should fall under state control. This view held considerable sway within the Nazi party, representing a common stance. For Hitler, this approach was integral to his concept of a society where private interests were secondary to the collective good of the nation.

Robert Ley, one of the more famous Nazi leaders would even go on the record as stating:

“Today the owner can no longer tell us, 'my factory is my private affair.' That was before; that’s over now. The people inside of it depend on his factory for their contentment, and these people belong to us.... This is no longer a private affair, this is a public matter. And he must think and act accordingly and answer for it."

— Robert Ley quoted in Hitler's Revolution by Richard Tedor,

Hitler's official policies aligned with the sentiments expressed by Robert Ley, as mentioned above. However, it was Otto Strasser who took a more radical stance on class warfare and advocated for the interests of the proletariat within the Nazi party. As early as 1925, Gregor Strasser also called for an "economic revolution" that included the nationalization of the economy, which he expressed in a speech to the Reichstag. Tensions escalated in early 1930 when trade unions in Saxony declared a general strike. Otto supported these strikes, while Hitler did not. In an attempt to bring Otto back in line, Hitler called him to a private meeting, but this failed to resolve the differences. Accusations were exchanged, with Hitler labeling Otto as a Marxist, and Otto accusing Hitler of being a capitalist demagogue.

The debate between Hitler and Otto Strasser in May 1930 further highlighted Hitler's views on socialism. Otto argued that worker ownership was a crucial aspect of National Socialism, but Hitler disagreed. When Otto advocated for "revolutionary socialism," Hitler dismissed the idea, suggesting that workers were too simple to understand socialism. Instead, Hitler believed that the state should have control over both workers and employers. He argued that workers taking charge of companies would only impede progress. In response to this, Strasser expressed dismay and referred to Hitler's stance as fascism.

Hitler continued with saying:

“A system that rests on anything other than authority downwards and responsibility upwards cannot really make decisions, Fascism offers us a model that we can absolutely replicate! As it is in the case of Fascism, the entrepreneurs and the workers of our National Socialist state sit side by side, equal in rights, the state strongly intervenes in the case of conflict to impose its decision and end economic disputes that put the life of the nation in danger.”

— Adolf Hitler quoted in Hitler vs Strasser, The Historic Debate of May 21st and 22nd 1930, by Otto Strasser

Otto Strasser fired back:

“Fascism has not found its way between capital and labor. It hasn’t even searched for it, it limits itself to containing social struggles by maintaining the all powerlessness of capital over labor. Fascism is not the overcoming of capitalism. On the contrary, until now in any case, it has maintained the capitalist system in its power, as you would do yourself.”

— Otto Strasser quoted in Hitler vs Strasser, The Historic Debate of May 21st and 22nd 1930, by Otto Strasser

Hans Reupke, a Nazi party economist who joined in 1930, echoed Hitler's views, emphasizing that corporatism formed the core of National Socialist economics. Another economist, Max Frauendorfer, concurred with Reupke, asserting that the Italian model offered the only alternative to Jewish Marxism and capitalism. Surprisingly, even Gregor Strasser aligned himself with Hitler on this matter, despite the divergence from his own brother, Otto. Otto vehemently rejected these arguments, with Erich Koch joining him in shouting, "We are not Fascists! We are Socialists!" During this debate, Otto also defended modern art as a vital and vibrant force. In response, Hitler branded Otto an "intellectual white Jew" and countered that true art resided in Platonic beauty found in Forms, positioning it as infallible, divine, and objective.

Following this famous debate, a rift emerged between Gregor and his own brother, shedding light on the actual differences at play. Otto Strasser was not a fascist but rather a proponent of Guild Socialism. Hitler's focus within National Socialism revolved around a state-driven approach similar to fascism. Fascist economics relied on corporatism, a nationalized form of syndicalism, which was contingent upon the trade union model. The Nazis implemented this by establishing their own state-sponsored union, the German Labor Front. This understanding also sheds light on the privatization efforts undertaken by the Nazis, which primarily benefitted party members rather than random individuals lacking ideological commitment. As argued in The Nazi Economic Recovery, privatization was often temporary and aimed at financing rearmament. Consequently, it can be said that the purported privatization was, in name only, serving as a facade for a state-backed monopolies. Dennis Sweeney posits that it was Hitler's form of state socialism that attracted many to the party and eventually won Gregor's loyalty.

“The Nazis, who invoked a Corporatist conception of workplace-organization as part of their larger plans for the “creation of a corporate social order” (Ständische Aufbau)[…] The Nazi leaders of the DAF reformulated their Corporatist plans for Ständische Aufbau in relation to the industrial workplace during the summer and fall of 1933, in ways that accommodated demands for autonomy and employer prerogative emanating from the ranks of German heavy industry. After 1933, Corporatist references to occupational “estates” and the “works community” combined with racial concerns about the worker’s body, individual “performance,” and the social and biological reproductive functions of the working-class family to shape ideological discourses about work and newly reconfigured factory regimes during the Nazi era. Bio-racial Corporatist terms and assumptions figured centrally in the writings and policies of Nazi physicians and scientists, industrial sociologists and efficiency experts and DAF functionaries. They also constituted the core of racist definitions of work, occupational hierarchies, and social order in the much vaunted “performance community” (Leistungsgemeinschaft) of the Third Reich. This was visible, for example in the rationalized industrial workplaces of the automotive firm Daimler-Benz, at the electrical firm Siemens, and in the plans for the National Socialist model factory of the Volkswagen concern. Most historians of corporatist ideology and Nazism have focused on the corporatism(s) of small producers (namely German retailers and shop owners), with their calls for guild-like organizations and guarantees of state protection.[…] Indeed, Hitler and several other Nazi leaders including Gottfried Feder, Otto Wilhelm Wagner, Gregor Strasser, and Max Frauendorfer were attracted to the Dirigiste Corporatist solutions to class conflict and the volatility of capitalist economies, especially to the “neoromantic” theories of the Viennese professor of political economy, Ottmar Spahn."

— Dennis Sweeney, Work, Race, and the Emergence of Radical Right Corporatism In Imperial Germany

As previously mentioned, the economic differences between the Strasser brothers became a significant factor in their growing distance from each other. Over time, Gregor began to align himself more closely with the official party stance and expressed his loyalty to Hitler.

Alfred Rosenberg elaborates further on this in his Memoirs:

“Otto Strasser came over to us from the camp of the Social Democrats, after having had close contacts with its leaders. I felt that he was less interested in following the party line of the National Socialist German Workers' Party than in propagating certain undigested ideas of his own. When he told me that he considered an entirely new economic structure of paramount importance, I replied that it wasn't sufficient to write a number of articles; what he should do was write a well-rounded, carefully thought-out book to give people a chance to study his ideas. This he did not do. The conflict came in spite of the fact that Hitler did his utmost to hold Strasser. Together with some of his followers, he seceded from the party. His brother Gregor remained. I still remember a discussion I had with Hitler a little later. Thank God, he said, that Gregor Strasser has remained true, a great thing for all of us. He was genuinely fond of him, even as Gregor Strasser proved his own brotherly love for Hitler by consoling him when his niece died and the Führer was considering giving up his entire political career.”

— Alfred Rosenberg, Memoirs

The ideological rift in economic thought between Otto Strasser and Hitler is rooted in their distinct philosophical leanings. Otto was an advocate for Guild Socialism, with elements of Catholic Distributism, whereas Hitler's economic ideology was based on Corporatism, influenced by the State Socialist policies of Otto von Bismarck and the "Historical School of Economics." This translated to Hitler advocating for a hierarchical state-driven socialism, in contrast to Otto's vision of a grassroots, democratically-oriented socialism. Moreover, their understandings of National Socialism diverged sharply. Hitler insisted on the Führerprinzip, demanding unchallenged authority for the leader, while Otto refuted this as undemocratic, calling for a system that would hold the leader accountable. Hitler believed that such concentrated authority was essential to maintain order and achieve the nation's objectives.

Otto perceived National Socialism as an evolved form of socialism with a nationalistic twist, rooted in the natural tendencies of human society such as local governance, democratic participation, and workers' control over production. Hitler's vision of National Socialism was a form of socialism tailored for the German populace, binding the community on the basis of racial identity. The "people's community" was central to his ideology, with the aim of rallying Germans under a singular authority—Hitler—through the apparatus of the State, thereby conflating race with statehood. Otto, on the other hand, advocated for the distinction between state and race, promoting the self-governance of Germanic regions and the conservation of their distinct cultural heritages.

Otto championed the idea of a confederate Germany, where smaller, self-governing regions could maintain their distinct identities and autonomy. He viewed large-scale industry as a potential hindrance to this model. Moreover, Otto sought to break up the prevailing dominance of Prussian culture, which he believed monopolized power through the state's hierarchical organization. This vision starkly contrasted with Hitler's, who aimed to erase regional disparities to forge a more unified and centralized German identity. Otto's departure from the NSDAP in 1930 was partly due to the party's position on federalism.

In 1932, Otto Wagener drafted a new economic program, but it was never made official due to protests from Feder. Gregor Strasser's Immediate Economic Program, based on his Work and Bread speech, replaced it and was presented by the party in the July election. However, it was withdrawn in September, reportedly because Hitler deemed it too radical and potentially detrimental to his negotiations towards becoming Chancellor. It was replaced by the Aufbauprogramm, primarily authored by Feder. Gregor then advocated for the creation of a national pension system through a party syndicate, an idea supported by Robert Ley and Hitler. Like many others in the Nazi party, the Strasser brothers aimed to appeal to communists in the hopes of radicalizing them away from Marxism, a stance that Hitler also endorsed. The party-switching of communists to the Nazis, known as "Beefsteak Nazis," was estimated to be significant in numbers. Rudolf Diels, the head of the Gestapo from 1933 to 1934, reported that "70%" of new SA recruits in Berlin had previously been communists. This phenomenon was documented by historian Konrad Heiden in his 1936 book Hitler: A Biography, referring to these individuals as "beefsteaks" - brown (Nazi) on the outside but red (Communist) on the inside.

Hitler endorsed Gregor Strasser's new organizational strategy, which played a pivotal role in transforming the Nazi Party from a marginal fringe group to a mass-popular movement with a widespread presence across Germany. The NSDAP effectively appealed to the lower classes, capitalizing on their inclination towards socialist ideals. Gregor also fostered positive relationships with certain minor industrialists. One notable aspect of Gregor's economic approach was a new trade policy. While still advocating for protectionism in the agricultural and domestic product sectors, there was a greater emphasis on foreign trade. Gregor proposed reducing autarky and sought to address the issue of high unemployment by advocating for Germany to abandon the gold standard, nationalize banks, and initiate public works projects. Hitler, along with Feder, Wagener, and Ley, strongly supported these ideas. In fact, this economic recovery plan became the official policy of the Nazi party.

The Nazi Economic Miracle

Convinced by Hitler's practical approach, Gregor Strasser and Joseph Goebbels climbed the ranks within the Nazi Party, with Gregor ascending to the role of Propaganda Leader and Goebbels becoming the Gauleiter of Berlin. Over time, however, a rift developed between Otto Strasser and Hitler, resulting in Otto's refusal to yield to Hitler's directives. As a consequence, Hitler tasked Goebbels with the expulsion of Otto and his faction, whom he mockingly labeled as "Salon Bolsheviks."

In defiance, Otto, asserting his claim as the authentic National Socialist, established the Union of Revolutionary National Socialists, known as the Black Front, and castigated Hitler as "the betrayer of the revolution." While Otto did manage to draw away a considerable contingent from the NSDAP, he was unable to secure the allegiance of key figures, including that of his brother Gregor, with whom he would not mend fences until 1933. Otto's influence was notable in the Berlin SA uprising in 1931, which was orchestrated by Captain Walter Stennes and included SA dissidents with communist pasts. Otto provided counsel and encouragement to Stennes during this insurrection. Interestingly, Stennes would later covertly serve as a Soviet intelligence agent.

The authors James and Suzanne Pool, reached this conclusion that:

“The evidence indicates that Stennes was financed by several important industrialists who were intent on destroying the Nazis.”

— James Pool and Suzanne Pool, Who Financed Hitler

In his book Flight From Terror, Otto Strasser reveals that Jewish multimillionaires Otto Wolff, a steel and coal magnate, and Paul Silverberg, a financier, along with major German industrialist Hermann Bücher, were the chief financial benefactors of Walter Stennes. Their intent was to thwart Hitler's rise to power by all available means. Nevertheless, Hitler managed to intervene and sway the majority of SA members from aligning with Stennes and Otto. According to Otto, it was the Jewish and capitalist elite who funded the 1931 conspiracy involving himself and Walter Stennes. The Black Front accused the NSDAP and Hitler of taking kickbacks from German industrialists like Krupp and Thyssen, but it has been established that the party's financial support from capitalist sources was minimal, primarily coming from nationalist industrialist Emil Kirdorf.

The NSDAP primarily financed its activities through membership fees, entrance fees at meetings, and the sale of newspapers, writings, and books. On the other hand, the Black Front received support from more questionable sources, including Jewish capital from individuals like Silverberg and Wolff. This occurred because their interests aligned with the desires of the Black Front, the bourgeois class, and Jews to crush the NSDAP. Interestingly, while Otto conducted a relentless campaign against the Nazis, including launching severe attacks against Goebbels and Göring, his brother Gregor was accepted as a prominent member of the party. Newspapers under Otto's control cautiously criticized Hitler, suggesting that "National Socialism is bigger than Hitler," and so on. Goebbels noted in his diary that Gregor Strasser was treated well by a generally hostile press. This raised serious suspicions about Gregor's allegiance. Under intense pressure, Gregor wrote a letter to his estranged brother in 1932, with whom he had not spoken since leaving the Nazi party.

“I am unable to meet you. You are highly dangerous for your friends and a tonic for your enemies. Your articles have harmed me enormously… Everything which I had brought up for discussion in respectable circles fell largely on deaf ears because you, quite wrongly, gave the impression that I was in touch undercover with you.”

— Gregor Strasser’s letter to Otto Strasser, December 1932

Paul von Hindenburg, the President of Germany at the time, desired Kurt von Schleicher to become the Chancellor and extended an invitation to Gregor Strasser to serve as his deputy. Hindenburg and Schleicher hoped that Gregor's involvement would disrupt Hitler's party. Hitler, however, opposed this move, viewing it as an attempt to create a rift within the NSDAP. He also accused Gregor of being a traitor. In order to maintain party unity and prove his innocence, Gregor decided to resign from all party positions. With Hitler's approval, on the condition that he ceased all political activity, Gregor found employment in a large chemical firm. During this period, Gregor completely withdrew from politics.

Ernst Hanfstaengel here explains the strategy being used against Hitler:

"His plan was to split off the Strasser wing of the Nazi Party in a final effort to find a majority with the Weimar Socialists and Centre. The idea was by no means so ill-conceived and amidst the momentary demoralization and monetary confusion in the Nazi ranks, very nearly came off."

— Ernst Hanfstaengel, Hitler: The Memoir of the Nazi Insider Who Turned Against the Fuhrer

It is well-documented that Adolf Hitler was able to outperform Otto Strasser in various aspects. Hitler's ability to organize and hold larger rallies, as well as his success in winning seats in government, surpassed those of the Black Front. Furthermore, the NSDAP was more successful in infiltrating the Black Front than the reverse. They were able to disrupt meetings, uncover plots against their party, and even physically confront Otto, although he managed to defend himself by brandishing a pistol.

Hitler's rise to power began in 1933 when he became Chancellor of Germany, followed by his assumption of the presidency in 1934. One of his first actions as the leader was to ban the Black Front, prompting Otto Strasser to go into hiding. Prior to his disappearance, Otto instructed his remaining followers to infiltrate the NSDAP and prepare for a revolution that ultimately did not materialize. Unfortunately, many of his supporters were apprehended and subsequently sent to concentration camps, alongside communists and social democrats.

During the infamous Night of the Long Knives, which took place from June 30th to July 2nd, 1934, Hitler effectively neutralized the leadership of the SA. Gregor Strasser, in particular, met a tragic fate. He was arrested by the Gestapo on June 30th as part of the purge targeting socialists. After being taken to Gestapo Headquarters, Gregor was shot in the back of the head. Shockingly, he did not die instantly but was left in his cell to bleed to death slowly. The purge of the SA remained secret until Hitler announced it on July 13th, during which he coined the term "Night of the Long Knives." Hitler claimed that 61 individuals were executed, 13 were shot while resisting arrest, and three committed suicide. However, some accounts suggest that the actual death toll may have been as high as 400. In his speech, Hitler justified his decision to bypass the judicial system, asserting his authority as the supreme judge of the German people and ordering the execution of the conspirators.

Article announcing the SA purge.

Following these events, Gregor's brother, Otto Strasser, chose to go into exile. Alfred Rosenberg adds more context in his Memoirs:

“During the Röhm-Putsch Strasser and Schleicher were killed. We all thought they had been involved in some way, but the police remained silent. The Führer made arrangements for the financial security of Strasser's widow, an extremely pleasant woman. In the Second World War both of Strasser's sons fell as officers at the front. This is the sort of tragedy that is inevitable in the course of a revolution. Whenever I think of Strasser as he was in those days, I see before my eyes his tall figure and his light, kind eyes. I remember his generosity, and, occasionally, also that apparent uncertainty which eventually led him to his doom. As the Führer told me later, he had intended to make Strasser his Secretary of the Interior. In that case, many things might have taken a different turn.”

— Alfred Rosenberg, Memoirs

In Volume 1 of Der Grosse Wendig: Richtigstellungen zur Zeitgeschichte, the section titled "Lügen über den 30. Juni 1934" supports the assertions made by Rosenberg. Historian David Irving similarly reflects this viewpoint in his book The War Path.

“Much had in fact happened that unsettled Hitler. Göring had wantonly liquidated Gregor Strasser, Hitler’s rival, and there had been a rash of killings in Bavaria... Hitler’s adjutant Brückner later described in private papers how Hitler vented his annoyance on Himmler when the Reichsführer SS appeared at the chancellery with a final list of the victims eighty-two all told. In later months, Viktor Lutze told anybody who would listen that the Führer had originally listed only seven men; he had offered Röhm suicide, and when Röhm declined this ‘offer’ Hitler had him shot too. Hitler’s seven had become seventeen, and then eighty-two.”

— David Irving, The War Path

The available evidence suggests that Adolf Hitler only authorized the execution of seven fellow Nazis during the "Night of the Long Knives." He was unaware of the extent of the killings until later, at which point he expressed irritation at the excessive actions. Hitler took responsibility for the events, ordered an investigation into those responsible for the excesses, and ensured that they were punished. He also provided state pensions to the families of those who died unnecessarily, including Gregor Strasser's wife and sons, as mentioned in Alfred Rosenberg's memoirs.

In Peter Stachura's biography of Gregor Strasser, titled Gregor Strasser and The Rise of Nazism, it is mentioned that Gregor had meetings with Hitler in late 1933 and early 1934, discussing the possibility of him joining the new government. This is supported by Rosenberg's memoirs. It was Heinrich Himmler and Hermann Göring who compiled the death lists, as they viewed Gregor as a threat to their own power within the party. Gregor was considered for significant roles within the Nazi party, including Minister of Economics, Minister of Labor, or Minister for the Interior. The idea that Gregor was executed simply for his socialist views is challenged by the real motives behind his death, which were largely influenced by the internal power dynamics between Göring and Himmler, coupled with Gregor’s outspoken criticism of both figures within the Nazi Party. Otto Strasser’s memoir 'Hitler und ich' lends credence to these factors, despite some inconsistencies with his other accounts. Additionally, the survival and promotion of Robert Ley, a notably leftist member of the Nazi party, to the head of the German Labor Front, as well as the immunity of other socialist-inclined members like Joseph Goebbels or Gottfried Feder, further disputes the assertion that Gregor was targeted solely for his socialist ideology.

It is important to clarify that Strasserism is often mistakenly labeled as a form of National Bolshevism. While Otto Strasser did have connections with Karl Otto Paetel, the leader of the German National Bolshevik party through Ernst Jünger, Paetel did not hold a favorable view of Otto's ideology. Both Paetel and Otto opposed Hitler and Fascism, but Paetel criticized Otto for promoting a form of Feudal Socialism, considering him to be anti-scientific and foolish in his beliefs.

Paetel argued in The National Bolshevik Manifesto of 1933:

“All the Problems Strasser has with Marx, would be solved by Reading Marx.”

— Karl Otto Paetel, The National Bolshevik Manifesto

It is worth noting that Paetel, held extreme views, such as pagan supremacism. Paetel was critical of Hitler, whom he insulted as a "political Catholic," implying that Hitler's religious beliefs influenced his political actions. Additionally, Paetel derogatorily referred to Otto Strasser as a "Jew worshiper.”

Paetel went on to say this:

“They must free themselves from the shackles of Christianity which stunts their heroism and makes them susceptible to enslavement by Rome."

— Karl Otto Paetel, The National Bolshevik Manifesto

It's crucial to recognize that Otto's beliefs did not align with fundamental Marxist tenets like Dialectical Materialism or internationalism. His divergence from Marxist ideology drew criticism from Karl Otto Paetel, a materialist who considered nationalism an instrumental step towards internationalism. Despite some level of association between Otto and Paetel, the latter rebuked Otto for his support of a German confederation, contending that Hitler's idea of a centralized German Federalist State was a more fitting concept. Paetel's critique carries weight, especially as he was an ardent critic of Hitlerism. He also disapproved of Otto's radical agrarian emphasis, which he feared would cripple German industry. As a proponent of Marxist economic principles, Paetel viewed this as harmful to national interests and favored continued industrial growth. Otto sought alliances with figures of the Conservative Revolution, including Ernst Jünger, as well as with Kurt Hiller, a Jewish communist and proponent of gay rights, and National Bolshevik theorists like Karl Otto Paetel and Ernst Niekisch. Nevertheless, their collective endeavors to counter Hitler did not succeed.

In his work Germany Tomorrow, Otto Strasser criticized both Hitler and Stalin as "totalitarian." He viewed them as cut from the same cloth, arguing that the 1939 Soviet-German Non-Aggression Pact openly demonstrated the close relationship between the two systems. Otto characterized Hitler as launching a war against Europe in concert with Stalin. When discussing his own economic ideas, Otto also criticized both Fascists and Communists for excessively strengthening the state's control over the economy and infringing upon individual rights.

“Fascists and communists are the first to exalt the state, the first to repress economic and personal independence, the first to exalt the excesses of power, the success of organization, decree, planning, and - last but not least - the police.”

— Otto Strasser, Germany Tomorrow

Otto Strasser engaged in collaboration with Communist and Jewish groups through his Black Front organization from 1930 to 1934, during a period when they sought to divide the NSDAP. In early 1931, the Black Front attempted to align with the Communist group Antifaschistische Aktion, commonly known as Antifa. While the Antifascists considered the Nazi party as one of the fascist parties, they also aimed to appeal to Strasserists by utilizing nationalist slogans. It is worth noting that Otto collaborated with the British Secret Intelligence Service, also known as MI6, indicating his involvement as a traitor.

Sefton Delmer, an expert in British black propaganda during World War II and the creator of the black radio station "Gustav Siegfried eins," mentioned in his autobiography Trail Sinister that one of his inspirations was a secret black propaganda radio transmitter operated by Otto Strasser in Czechoslovakia. The radio engineer Rudolf Formis, who had to flee Germany after being exposed as a saboteur, operated this radio station. This station disseminated grossly fabricated falsehoods about Hitler and others. It should be noted that many of the unsubstantiated claims regarding sexual perversion among prominent National Socialists originate from Otto Strasser. Otto's black radio transmitter received financial support from Jewish individuals and operated under the protection of the Czechoslovakian government. Otto Strasser even relayed a completely unfounded claim to the OSS (Office of Strategic Services) that Hitler had subjected Geli Raubal to humiliating acts. However, there is no evidence to support this allegation.

The Jew Dr. Kurt Hiller, who got to know Otto Strasser during Strasser’s long stay in Czechoslovakia, writes:

”Since 1930, first in Germany and then in exile, he [Strasser] waged an unfailing and brave fight against the werewolf [Hitler] in Germany.”

— Kurt Hiller quoted in Towards a Fourth Reich? The History of National Bolshevism In Germany by Klemens von Klemperer

According to the book Men Against Hitler by Fritz Max Cahen, a Jewish individual, he claims to have regularly met with Otto Strasser during his fight against National Socialist Germany, where he played a leading role in the "German" resistance. It is also worth noting that Otto Strasser had contacts with the Jewish interior minister of France at the beginning of the war.

Even more interesting is that the periodical of World Jewry in 28th August, 1936 carried the following report from its Prague correspondent:

“The well-known rival of Herr Hitler, Otto Strasser has published an appeal to the German Jewish emigrants to join the newly-formed organization of German Jews headed by Herr Rossheim. In his opinion, the solution to the problem of the Jews in Germany lies in the direction of assimilation.”

— World Jewry in 28th August, 1936

Historian Henry Ashby Turner has pointed out that a significant aspect of Hitler's socialism was his fervent belief in antisemitism. However, Otto Strasser held strong criticisms of the Jewish Question and biological racism. Otto proposed two options for Jews: either they could become a national minority with their own autonomous region, which also applied to other races, or they could fully assimilate into Germany, renouncing their religion and adopting Christianity. This stands in stark contrast to Hitler's views, as Hitler sought to deport Jews from Germany.

Otto Strasser viewed Jews as he would any other race, believing that consistent cultural interaction would lead to conflicts. In other words, Strasser believed that eliminating cultural differences would resolve internal conflicts. On the other hand, Hitlerism posits that as long as a society remains multicultural, chaos will ensue because, in Hitler's perspective, culture is linked to race and therefore considered the same. In fact, in 1928, Otto Strasser proclaimed, "Anti-semitism is dead. Long live the idea of the people!" In 1938, Otto Strasser relocated to Switzerland and subsequently to France. The British ambassador in Berlin, in a letter to the British Foreign Secretary on the 18th July 1939, said:

“So many people, such as Otto Strasser and others of this world are seeking with intense pertinacity to drive us to war with Germany.”

— Sir Neville Henderson, July 18, 1939

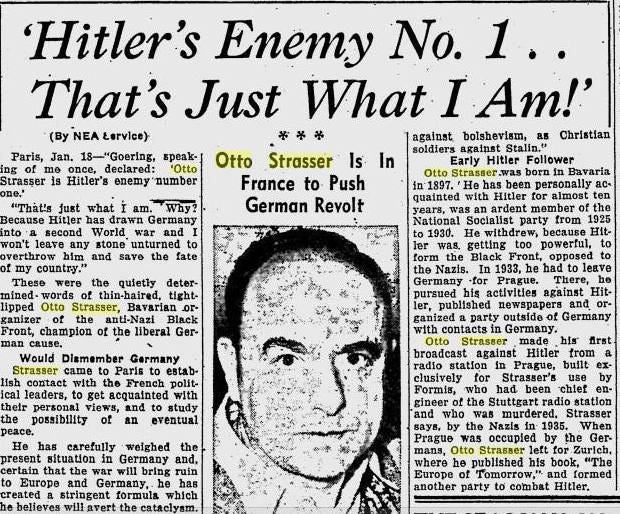

"Otto Strasser... champion of the liberal German cause”

According to W.J. West in The Truth Betrayed, there were strong links between Otto Strasser and the British authorities, specifically through Sir Robert Vansittart, the Permanent Head of the Foreign Office and later Chief Diplomatic Advisor to the Government. Vansittart recommended Otto Strasser and Hermann Rauschning to the Foreign Secretary in October 1939. Another defector, responsible for a book filled with lies titled Hitler Speaks, exposed by Swiss historian Wolfgang Haenel.

After the failed bomb plot at the Burgerbraukeller in November 1939, which aimed to kill Hitler and was believed to have been masterminded by the British Secret Service through Otto Strasser, Vansittart turned against Otto, implying that his reputation was tied to the plot. Material from Otto Strasser was used in the book Der Führer, which was attributed to Konrad Heiden and played a role in formulating the indictment at the Nuremberg Trials. Otto's material was also utilized by Dr. William C. Langer in his book The Mind of Adolf Hitler, a piece of wartime propaganda assigned by the American OSS, now the CIA. Otto Strasser fled from Austria to Czechoslovakia, Switzerland, France, and eventually Canada. During his time outside of Germany, he gave lectures and speeches against the regime and attempted to organize the remaining members of his Black Front organization. Otto also made a direct attack on the NSDAP headquarters in Nuremberg, but the plot was discovered and the attacker, Helmut Hirsch, a German Jew, was executed. Nazi agents made several attempts to capture Otto, but he always managed to escape.

He collaborated with both the Austrian and Czechoslovakian governments, but was eventually pressured to leave due to the influence of the NSDAP and the imminent German invasion. Otto then resided in Canada, where he collaborated with the British government, wrote for the New Statesman, and authored his biography Hitler and I and his book Germany Tomorrow. For a brief period in 1940-1941, Otto Strasser was an international celebrity with a realistic chance of becoming the leader of a reconstructed post-war West Germany. Warner Bros even acquired the rights to make a movie about his life. Otto attempted to smuggle his two books into Germany to incite a revolution against Hitler. However, Canada prohibited him from publishing political writings in 1943 due to his ideology and past associations with the Nazi party, which left Otto bitter. His momentary celebrity status soon faded completely.

After World War II, Otto Strasser was invited to join the German Democratic Republic (DDR), the East German Communist government, but he refused. Other former Nazis, like Bruno Fricke and Otto Ernst Remer, were enthusiastic about the DDR, seeing in it the opportunity to reinvent and revive National Socialism by working with the Soviet Union. Otto rejected the idea of joining the DDR, as he found the integration of Hitlerists into its government repugnant. He also saw being part of a puppet regime as pointless.

Otto being invited to the DDR

After returning to West Germany, Otto Strasser founded his own party called the German Social Union. However, the party did not gain much traction and eventually disintegrated in 1962. Otto also participated in the European Social Movement and the National European party, which advocated for a unified European state and included various nationalist and fascist parties such as Oswald Mosley's Union Movement, Jeune Europe, the Italian Social Movement, and the Socialist Reich party. Within these groups, Otto engaged in debates on foreign policy, taking a more pro-Soviet stance and arguing with some members about the Holocaust. Otto maintained contact with Jean Francis Thirart, who shared similar ideas and would later influence Alexander Dugin. Throughout the rest of his life, Otto Strasser sought to defend his ideas and actions while distancing himself from Hitler's National Socialism. It was only after his death that some nationalist circles embraced some of his ideas, such as The Other Russia. Otto passed away from natural causes in March 1974. Although he outlived many NSDAP leaders and rivals, he was not as influential as others in the movement.

Conclusions

In my view, had Strasserism risen to prominence, it's doubtful that Hitler's brand of National Socialism would have achieved the same level of power. Otto Strasser's distinct ideology might have fragmented the support base critical to Hitler's ascension, making it improbable for Otto to captivate the nation as Hitler did. Throughout his political endeavors, Otto was a thorn in the side of the Nazi hierarchy, often regarded as a disruptive element. National Socialism is more complex than the simplistic fusion of socialism and nationalism that Strasserism seems to suggest. It is deeply intertwined with the notion of the Volksgemeinschaft, or National Community, which posits that racial solidarity both justifies and necessitates profound social reform, underscored by the Führerprinzip, or leadership principle.

While National Socialism does call for the regulation and oversight of private property to serve the nation's interests and promote equitable distribution, it stops short of demanding full nationalization as the only path to social equity and opposes the unchecked disparities inherent in liberal capitalism. The depiction of Hitler as a staunch advocate of private property rights or as a capitalist is a mischaracterization that is often circulated either through misinformation or deliberate distortion. Hitler consistently prioritized the objectives of the state. Even Richard Wolff, a Marxist economist of Jewish heritage, with his definition of socialism, Hitler could be placed within the broad spectrum of socialist thought.

Professor Richard Wolff explaining socialism

Even more fascinating is that these various quotes from The Vampire Economy by the communist economist Günter Reimann show the reality for big business under the Nazis.

“I must confess that I think as most German businessmen do who today fear National Socialism as much as they did Communism in 1932. But there is a distinction. In 1932, the fear of Communism was a phantom; today National Socialism is a terrible reality. Business friends of mine are convinced that it will be the turn of the ‘white Jews' (which means us, Aryan businessmen) after the Jews have been expropriated… The difference between this and the Russian system is much less than you think, despite the fact that we are still independent businessmen.”

“You have no idea how far state control goes and how much power the Nazi representatives have over our work. . . In this respect they certainly differ from the former Social-Democratic officials. These Nazi radicals think of nothing except ‘distributing the wealth.’ Some businessmen have even started studying Marxist theories, so that they will have a better understanding of the present economic system.”

“You cannot imagine how taxation has increased. Yet everyone is afraid to complain about it. The new State loans are nothing but confiscation of private property, because no one believes that the Government will ever make repayment, not even pay interest after the first few years.”

“The old type of capitalist who adheres to the traditional concepts of property rights is doomed to failure under Fascism.”

— Günter Reimann, The Vampire Economy

The notion that Strasserism was the exclusive embodiment of left-wing socialist thought within the Nazi Party is incorrect. Figures like Rudolf Jung, Robert Ley, Gottfried Feder, and Joseph Goebbels, who were socialist in orientation, remained devoted to Hitler and significantly shaped the policies of the Nazi regime. I believe that modern Strasserists mistakenly accuse Hitler of yielding to the interests of big businesses and betraying his original cause and followers. The key consideration should not be whether Hitler received financial backing from industrialists or other sources, but if such contributions swayed his convictions and guiding principles. A careful analysis of the historical record clearly indicates that Hitler stood firm in his objectives and maintained authority over his movement, regardless of where the funds originated.

There is no substantial historical evidence to suggest that Hitler was ever influenced by financial transactions. He consistently dominated the political landscape, regardless of what his financial backers may have hoped for. Conversely, Otto Strasser himself accepted funds from bourgeois sources and sought support from foreign governments in opposition to Hitler. He was involved in plots to assassinate Hitler, worked alongside Jews and communists, dismissed the importance of race and antisemitism, testified at the Nuremberg Trials which led to the execution of Nazi leaders, and was spreading lies about Hitler both during and after the war. From what I have gathered, Hitler had plans to evolve Germany into a renewed socialist republic after the war, featuring a senate and a parliament. As part of this vision, there would be arrangements for electing a successor executive who would wield absolute power, much like Hitler himself did. Those interested in exploring this topic further can refer to books such as Hitler's Table Talks and Hitler: Memoirs of a Confidant. Historian Roger Griffin, in The Nature of Fascism, posited that the Strasser brothers held differing views on their loyalty to the NSDAP:

“Gregor Strasser remained faithful to Nazism while his brother Otto was its bitter critic.”

— Roger Griffin, The Nature of Fascism

A thorough analysis reveals that Gregor Strasser was a devoted adherent of National Socialism and true to Hitler, making it ethically dubious, from my perspective, for Hitler's followers to celebrate his demise. Conversely, Otto Strasser was indeed a betrayer. While Strasserism is often categorized under the umbrella of National Socialism due to its origins and its combined emphasis on nationalism and socialism, the two ideologies were inherently distinct. The idea that Gregor was in league with Otto is mostly rooted in a fabricated narrative, one that Otto himself initially promoted and which the ill-informed continue to endorse. This narrative paints a picture of a cohesive leftist bloc within the NSDAP that could have altered history's course and avoided its darkest chapters, bearing a resemblance to Trotskyism. Otto was so engulfed in his own narrative that he neglected to acknowledge its repercussions on others. Years after the war's end, he persisted in portraying Gregor as having been in ideological lockstep with him, notwithstanding their clear differences. Otto even tried to leverage Gregor's ashes for political ends, against the explicit wishes of Gregor's widow who implored that her late husband's memory not be exploited for political purposes.

Delving deeper into the subject, it becomes apparent that Otto Strasser's accounts are marred by fabrications and self-aggrandizing falsehoods intended to enhance his own stature and cast himself and his brother Gregor as allied opponents of Hitler's regime. However, the truth is more complex: Gregor's stance on Hitler was more ambivalent, and by 1930, his views had shifted towards the moderate-conservative wing of National Socialism. The idea of a unified "Strasser brothers" or a cohesive "Strasser wing" is a myth. Peter Stachura's book, Gregor Strasser and The Rise of Nazism, presents a realistic picture, depicting Otto as an opportunist who stirred trouble and whose ideology lacked substance and coherence. In contrast, Gregor is shown as a more grounded person and a committed member of the Nazi Party, though not particularly aligned with leftist ideologies.

Towards the latter part of his political life, he even showed a willingness to form alliances with conservative figures, including Hitler. Stachura, like myself, concludes that there was no significant "Strasser bloc" within the Nazi movement, and that Otto fabricated claims of Gregor's allegiance post his own expulsion. Gregor's actual support for Otto was marginal at best, and Otto's notoriety largely stems from his relation to Gregor and his propensity for causing a stir. One could speculate that, had Otto refrained from making false claims about Gregor, his brother might have survived longer. However, this remains conjecture. The tragic consequence is that Gregor Strasser's legacy has been tarnished by Otto's folly. He is either maligned by some Hitler supporters out of ignorance or erroneously idolized by Otto's adherents. Gregor's loyalty to Hitler persisted to the end, as evidenced by his resignation letter, which reaffirmed his dedication to National Socialism.