Corporatism: An Introduction to Fascist Economics

by Zoltanous

1. Introduction and a Basic Argument For Corporatism.

When the term "Corporatism" is mentioned, it often evokes thoughts of cronyism and Fascism, but this association should be challenged. Corporatism should not be linked to cronyism (corporatocracy) and, in fact, stands in direct opposition to it. Corporatism advocates for a complete rejection of the dominance of Mammon. It should not be confused with modern capitalist entities commonly referred to as "corporations." The term itself has much older roots, referring to the guilds in Italy known as "Corporazioni delle Arti e dei Mestieri" (Corporations of Arts and Crafts). However, the doctrine of Corporatism predates even these guilds, with various theorists and political figures approaching it from different perspectives. Elements of Corporatism can be found within feudal societies and in the political writings of Christian thinkers like St. Thomas Aquinas.

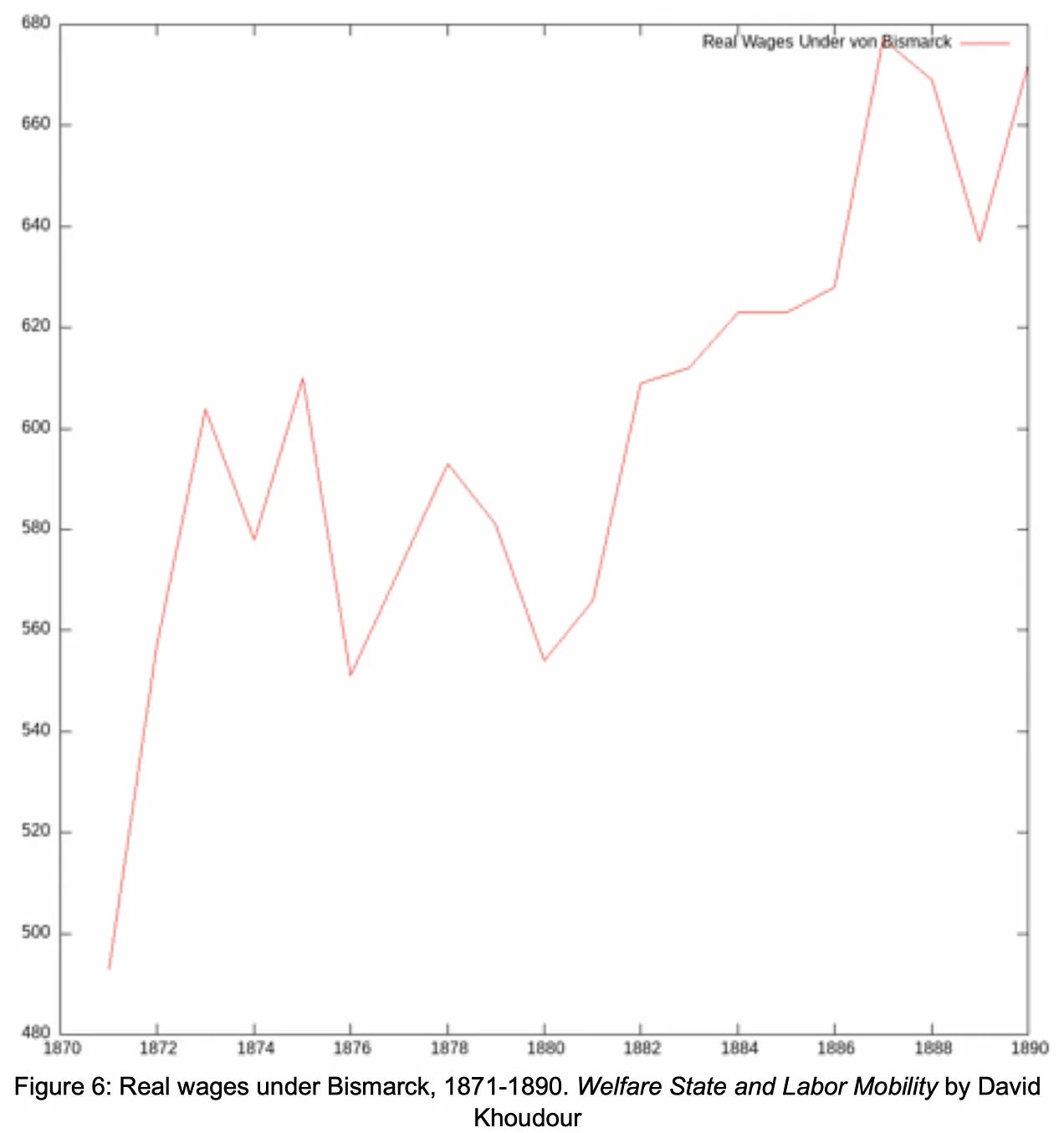

While Corporatism is an integral part of National Socialism and Fascism, its scope extends beyond these two ideologies. For instance, Portugal under Antonio de Oliveira Salazar implemented a Corporatist system, but Salazar himself was neither a Fascist nor a National Socialist, as he viewed Fascism as "Pagan Caesarism" and suppressed the National Syndicalists in his country. Instead, his Corporatism was rooted in his Catholicism. Similarly, in the former Portuguese colony of Brazil, the leader Getúlio Vargas established a non-Fascist Corporate state. The same can be said of King Carol II in Romania, who violently suppressed the Iron Guard after establishing a royal dictatorship in the late 1930s. There are even older examples that may not have used the term "Corporatism," such as Otto von Bismarck's State Socialism, which did not label its system as Corporatist but can be considered a variation of it.

So, what exactly is Corporatism? Simply put, Corporatism is a system of representation that places all societal interests under the authority of the nation as a whole by establishing occupational trade associations like guilds, unions, and labor courts. We can observe similar organizations even in non-Corporatist states, such as labor courts in certain American states like Kansas and Pennsylvania. Furthermore, we can see that unions in non-Corporatist societies often lack effective governance, which is exemplified in the case of America. In a Corporatist society, unions are integrated into the state apparatus, preventing them from causing significant economic damage. This defense of Corporatism is also a defense of nationalism. Firstly, we view these two concepts as interconnected. Secondly, the main argument for Corporatism is built upon nationalism. Corporatism not only has a historical connection to nationalism but also requires adherence to nationalist principles.

As far back as the 18th century, capital has been regarded as a force that opposes nationalism. Under liberal capitalism, large corporations prioritize their own private interests over the national interest. This behavior poses a threat to a nation's customs, culture, and traditions, especially if these elements are perceived as hindrances to maximizing profit. This is why we often witness a push for globalism, immigration, and other policies that are viewed as anti-nationalist, driven by the influence of the plutocratic capitalist class on the state apparatus. No group should be allowed to advance itself at the expense of the nation and a unified society. Therefore, capitalism, by its very nature, is inherently anti-nationalistic. It is essential to establish a de facto supremacy of the state and abandon the dogma of laissez-faire. However, these measures alone do not guarantee harmony. It is important to focus on the United States in this context. In 2014, a study conducted by Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page examined 1,779 policy changes between 1981 and 2002. Their findings revealed that policy decisions are primarily influenced by elite opinions, followed to a lesser extent by interest groups.

“In the United States, our findings indicate, the majority does not rule—at least not in the causal sense of actually determining policy outcomes. When a majority of citizens disagrees with economic elites or with organized interests, they generally lose. Moreover, because of the strong status quo bias built into the U.S. political system, even when fairly large majorities of Americans favor policy change, they generally do not get it.”

—Gilens, M; Page, Benjamin I (2014). Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens; page 24.

In a study published in 2015, Martin Gilens analyzed 2,245 policy shifts from 1964 to 2006 and discovered comparable results. He found that when the policy preferences of the less wealthy Americans diverge from those of the wealthiest, the former's opinions almost never influence policy decisions. Gilens' research indicates that for the bottom 90% of income earners in the U.S., the likelihood of their preferred policies being adopted is roughly 30%, no matter how popular or unpopular those policies are. In contrast, the viewpoints of the elite, particularly the top ten percent, have a significantly higher correlation with the policies that are ultimately enacted, especially regarding issues they oppose.

“Despite the seemingly strong empirical support in previous studies for theories of majoritarian democracy, our analyses suggest that majorities of the American public actually have little influence over the policies our government adopts. Americans do enjoy many features central to democratic governance, such as regular elections, freedom of speech and association, and a widespread (if still contested) franchise. But we believe that if policymaking is dominated by powerful business organizations and a small number of affluent Americans, then America’s claims to being a democratic society are seriously threatened.”

—Gilens, M; Page, Benjamin I (2014). Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens; page 24.

The underlying assertion is that state decisions are significantly swayed by a capitalist elite. This viewpoint maintains that liberalism, due to its emphasis on capital interests, often stands in opposition to the welfare of the nation. Taking the LGBT movement as an example, it's argued here that such social movements are influenced by capitalism. This includes the influence of Gender Accelerationism and the backing by the private sector of “woke” ideology, contributing to the economic cronyism apparent in society. Michael Franzese, once a leader of the Colombo crime family, provides insightful analysis on these matters.

“Corporate lobbyists are embedded in Congressional staff. They provide data, polling information, white papers, and policy recommendations that Hill staffers depend on to create new regulations or revise policies.”

—Franzese, Michael (2022). Mafia Democracy: How Our Republic Became a Mob Racket. Nevada: Lioncrest Publishing; page 64.

“Al Capone was right when he said, ‘Capitalism is the legitimate racket of the ruling class.’ I couldn’t agree more. Both parties are guilty. In 2015, the billionaire Koch brothers brought together a group of big spenders for a retreat in Palm Springs, California. There, they unveiled a plan to raise around $1 billion dollars before the primaries started, giving the group unprecedented influence over who the likely Republican candidate would be. Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, and Rand Paul all showed up to chat and stick out their hands. Democrats like George Soros and Tom Steyer also dole out millions to progressive candidates, giving the two of them an outsized influence over elections.”

—Franzese, Michael (2022). Mafia Democracy: How Our Republic Became a Mob Racket. Nevada: Lioncrest Publishing; page 77.

“In truth, the CEOs and elected officials on the House Financial Services Committee weren’t adversaries. They were partners. They were conspirators. They relied on each other-the congressman for campaign money and the CEOs for the billions in free money they needed to correct their mistakes. What a life! What’s more, when politicians and policy experts leave Washington, many go to work at places like Goldman Sachs. When the government needs help writing financial regulations, they recruit executives from places like Goldman Sachs. It’s a revolving door. It’s why Capitol Hill is often referred to as government sachs.”

—Franzese, Michael (2022). Mafia Democracy: How Our Republic Became a Mob Racket. Nevada: Lioncrest Publishing; page 79.

Corporatism aims to subordinate all societal interests to the nation as a whole, effectively challenging the dominance of Mammon. In this context, the phenomenon of lobbying would not exist, which I will elaborate on further. On the other hand, the class struggle advocated by Marxism and the initial form of syndicalism (which later evolved into Fascism) is also anti-national. Both Liberal Capitalism and Marxist Communism should be considered as opposing nationalist principles. According to Marx, Corporatism is viewed as reactionary because:

“Marx does not seem to have asked himself what would happen if the economic system were on the downgrade; he never dreamt of the possibility of a revolution which would return to the past, or even social conservation as its ideal. We see nowadays that such a revolution might eventually come to pass; the friends of Jaures, the clerics, and the democrats all take the middle ages as their idea for the future; they would like competition to be tempered, riches limited, production subordinated to needs. These are dreams which Marx looked upon as reactionary, and consequently negligible, because it seems to him that capitalism embarked on irreversible progress; but nowadays we see considerable forces grouped together in the endeavor to reform the capitalist economic system by bringing it, with the aid of laws, nearer to the medieval idea.”

—Sorel, Georges (1908). Reflections on Violence. London: George Allen & Unwin LTD., 1925; pages 91-92.

In the Communist manifesto, Marx referred to certain forms of Corporatism as "reactionary socialism" and "Petty-Bourgeois." He also labeled Pierre Proudhon as a "Conservative" and a "Bourgeois Socialist." Marx considered the socialism advocated by François-Noël Babeuf, Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, and Robert Owen as conservative, despite their status as early revolutionary proletarians. Marx believed that they "necessarily had a reactionary character" and considered all their followers to be reactionary as well.

Marx's tendency to label concepts as reactionary is influenced by his specific, limited, and non-empirical approach to socialism. In Marx's view, Proudhon is tagged as "Conservative" and "Bourgeois" for endorsing policies like protective tariffs that favor the working class. Marx categorizes Proudhon's mutualism, which maintains markets in the absence of a state, as fundamentally "Bourgeois." Furthermore, Marx overlooks Utopian socialists who focus less on class conflict and more on societal improvement as a whole. He does not align the adherents of Fourier and Owen with his ideology, despite their revolutionary intent. It's crucial to recognize that while Corporatism can be reactionary and conservative, it can also embody revolutionary elements, as evidenced by Fascism.

2. The Problems of Capitalism

All economic systems have ethical implications, whether acknowledged or not. In order for a system to be prescriptive, it must be based on ethics, as prescriptions inherently involve ethical considerations. Economics should be subordinate to politics, and politics should be subordinate to ethics. Firstly, let's discuss how the individualist philosophy of Mammon is incompatible with nationalism, and then delve into how capitalism acts as an anti-national force. As previously mentioned, capitalism inevitably leads to the rise of a wealthy capitalist elite class that prioritizes its own interests above those of the nation. However, there are individuals who fail to understand this reality, whom I will refer to as "racist liberals." They idealize a romanticized version of a past era in American history characterized by both liberal values and racist capitalist society. However, they overlook the fact that this was merely the initial phase of a detrimental process. On the other hand, nationalism developed alongside the establishment of modern republics and the decline of dynastic states. It reached its true form with the Jacobins. While nationalism and capitalism are not inherently incompatible, it is worth noting that nationalism shares significant historical roots with socialism.

While capital is often seen as opposing the interests of a nation, it is essential to address certain aspects. Some argue that the racist statements made by classical liberals or the fact that the American founding fathers owned slaves contradict the principle of equality for all. These perspectives can be attributed to what I term as "racist liberalism," as it categorized Germans, Irish, and Italians as "swarthy" while considering only Anglo-Saxons and Ashkenazi Jews as "white." It is noteworthy that notable figures such as John Stuart Mill, Max Weber, and Isaiah Berlin acknowledged the significance of national identity, although Mill later became more critical of economic liberalism. Furthermore, referring to authoritarian liberals like Augusto Pinochet is irrelevant, as he was a puppet of the CIA. Both liberalism and Marxism view individuals, rather than communities, as the primary focus.

Allow me to present an infamous line from Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations for comparison with a line from Marx:

“It is certainly not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our lunch, but from the fact they take care of their interest. We do not turn to their humanity but to their egoism and we never speak to them of our needs, but of their gains. No one who is not a beggar ever chooses to depend above all on the benevolence of his fellow citizens, and even a beggar does not depend exclusively on it.”

—Smith, Adam (1776). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. New York: Random House, 1937; page 14.

Adam Smith perceives human beings as egoistic and individualistic agents. Similarly, Marx also acknowledges the individual within his framework.

The only force that brings them together and puts them in relation is that of their own profit, their particular advantage, and their private interests. And precisely because each one looks to himself only, and no one bothers about the rest, they do all, in agreement with a pre-established harmony of things, or under the auspices of an all- shrewd providence, for common profit, and the interest of all.”

—Marx, Karl (1867). Capital, Volume One. British Columbia: Modern Barbarian Press, 2018; page 123.

Some may argue that Marx's perspective displays a sense of agnosticism, but to me, it appears to be rooted in egoistic individualism disguised as a concern for the "common good." Fascist philosopher Giovanni Gentile astutely observed that both liberalism and Marxism are individualistic as they deny the existence of a reality that transcends material life and is measured by the individual. Gentile further asserts that materialists always tend to be individualists. In the context of liberalism, man is seen as inherently individualistic and driven by self-interest. Consequently, the nation becomes a somewhat abstract creation aimed at safeguarding property and individual negative rights. Similar ideas can be found in the physiocrats and certain market theories of the medieval Islamic world, albeit without the same level of individualism. Liberalism prioritizes the protection of capital and economic competition above all else.

Even in market theories of the Islamic world, thinkers like Ibn Khaldun highlight the significance of "sharia," the importance of "asabiyya" (social solidarity), and the concept of community (Ummah). Other Islamic scholars, such as Ibn Taimiyah, draw proto-Corporatist conclusions. In the Western tradition, liberal individualism has been challenged by thinkers like Aristotle and Hegel. This form of individualism leads to the atomization of society, breaking down ethnic bonds and the overall social fabric. Hegel and Aristotle share a similar understanding of ethical life, emphasizing the development of the self in relation to other individuals, such as the family, the state, and civil society (with the family being the foundational and most significant unit). This challenges the notions put forth by Hobbes, John Locke, and others.

“From these things it is evident, then, that the city belongs among the things that exist by nature, and that man is by nature a political animal. He who is without a city through nature rather than chance is either a mean sort or superior to man; he is “without clan, without law, without hearth,” like the person reproved by Homer; for the one who is such by nature has by this fact a desire for war, as if he were an isolated piece in a game of backgammon.”

—Aristotle (350 B.C.E). Politics. Chicago/London: The University of Chicago Press LTD., 2013; page 4.

The development of an individual is inherently tied to their interactions and relationships with other individuals. This notion is supported by the nature of language itself, which is not an innate quality but rather something acquired from an existing community. Therefore, the concept of isolated and de-ethnicized individuals coming together to form a commonwealth, as proposed in the idea of the Leviathan, is utterly absurd.

“In Hegel’s words, ‘ethical powers govern the life individuals and have their representation, their figure and phenomenical reality, precisely in individuals are their contingencies’ (§ 145). The Robinsonian abstract individualism typical of the Enlightenment is dialectically overturned into a concrete, communitarian and historically determined ethics. In such an ethics, the individual is projected into the concreteness of intersubjective and communitarian relations that make him, with Aristotle’s Politics […]”

—Fusaro, Diego (2018). Hegel and the Primacy of Politics: Taming the Wild Beast of the Market. London: Pertinent Press; page 126.

Hobbes can be seen as both reactionary and liberal, depending on the context. While his ideas have influenced liberal capitalism, particularly in terms of an atomized view of individuals, liberalism also draws from Hobbes its understanding of freedom. However, Hegel critiques this understanding of freedom and rights as false and materialistic, highlighting its limited focus on individualistic and negative freedoms and rights, with little regard for the nation or a deeper Stoic or Christian understanding of freedom. This perspective on freedom is challenged by Stoics, who question the true freedom of a meth addict every time they consume meth. Therefore, liberalism has historically been opposed to genuine nationalism.

It is important to clarify that nationalism encompasses more than just the promotion of national or race-based identity politics, contrary to what some "nationalists" may believe. True nationalism extends beyond a superficial semantic shift from tribalism. The misunderstanding of nationalism has given rise to movements such as National-Anarchism, White Nationalism, and Black Nationalism, which distort the true essence of nationalism to justify their contradictory beliefs. Eugen Weber, in his book Varieties of Fascism, explains that nationalism finds its roots in the Jacobins, particularly Napoleon Bonaparte's concept of nationalism (referred to as Bonapartism by Marx). Nationalism seeks to foster unity, harmony, and uplift the people of a nation, while liberalism, as a form of individualism, creates class conflicts and elevates one class above others. Corporatism shares the ethical principles of nationalism, emphasizing the Volksgemeinschaft (National Folk-Community). Inspired by Napoleon's populist reinterpretation of Jacobinism, the concept of Volksgemeinschaft in Nazi ideology shifted the focus of identity from the land and territory of a sovereign to the people and social bonds of a sovereign. Napoleon was not merely the "Emperor of France" but the "Emperor of the French," and similarly, Adolf Hitler was not just the "Leader of Germany" but the "Leader of the German People."

“Adolf Hitler has set his stamp on the word folk-community [Volksgemeinschaft]. This word is to make completely clear to the members of our people that the individual is nothing, when not a member of a community, and that the natural community is only the community of men of the same origin, same language, and same culture, i. e. the folk-community.”

“The folk-community is the natural presupposition for the existence of the whole people and indirectly, in the end, for the existence of each individual. Whoever wants to live and thrive in this world is obligated in the nature of things to orient his struggle for existence mainly toward the struggle for the vital rights of the folk-community and thus of the nation.”

“The folk-community is not spatially bounded; it includes all members of the people, without regard to residence or temporary place of abode; thus it includes also those who live outside the borders of the German state.”

—Murphy, Raymond E.; Stevens, Francis B.; Trivers, Howard; Roland, Joseph M. ed (et al., 1948). National Socialism: Basic Principles, Their Application by the Nazi Party's Foreign Organization, and the Use of Germans Abroad for Nazi Aims. Washington D.C: Government printing office; page 71.

The Volksgemeinschaft represents an organic community of ethnic individuals united by language, customs, traditions, economy, and heritage. It finds its awakening through the collective worldview of National Socialism, which combines the concepts of the nation and the state into a singular idea. Within the Volksgemeinschaft, every German, regardless of class, social standing, residence, political affiliation, or foreign citizenship, is bound together. Each member has an implicit duty to obey the will of the Volk (people), embodied in the Führer through the Führerprinzip (leader principle). Consequently, the social obligations of the Volksgemeinschaft determine and guide the economic decisions of every German worldwide. Regardless of their location or circumstances, Germans are expected to remain true and loyal to the obligations imposed by the Volksgemeinschaft.

Critics may argue that capital disregards the nation or lacks a sense of Volksgemeinschaft, but this viewpoint can face opposition from certain right-wing individuals. To illustrate this, let's consider the example of immigration and multiculturalism, a topic that generates wide-ranging opinions within the so-called "right-wing" spectrum. While immigration may benefit a select few (such as the reserve army of labor), it can harm others. The consequences can be observed in the loss of cultural identity among subsequent generations, leading them to seek solace in empty consumerism. Ryan Faulk's analysis further demonstrates this point:

“The entire budget deficit, along with some proportion of the national debt itself, are a function of black and hispanic populations. The net effect of these two populations, even after taking away all military spending from them, costs the US $822.5 billion per year.”

—Faulk, Ryan. (2020). Fiscal Impact by Race in 2018. The Alternative Hypothesis. Recovered by: [https://thealternativehypothesis.org/index.php/2020/03/19/fiscal-impact-by-race-in-2018/].

In the context of America, there is a concern that immigrants are benefiting from the system more than they contribute through taxes. It is important to note that the argument that "they take too much welfare" cannot solely be attributed to immigrants, as data shows that white individuals receive more in welfare benefits. However, white individuals also tend to contribute more back into the system compared to Hispanics and Blacks. Thus, it is not just one specific class benefiting at the expense of another, but rather the entire nation. This raises the question of why there is a strong push for policies that contribute to lower levels of altruism, increased distrust, a lower quality of life, and social isolation.

“Diversity does not produce ‘bad race relations’ or ethnically-defined group hostility, our findings suggest. Rather, inhabitants of diverse communities tend to withdraw from collective life, to distrust their neighbours, regardless of the colour of their skin, to withdraw even from close friends, to expect the worst from their community and its leaders, to volunteer less, give less to charity and work on community projects less often, to register to vote less, to agitate for social reform more, but have less faith that they can actually make a difference, and to huddle unhappily in front of the television.”

—Putnam, Robert D (2007). E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-first Century. The 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian Political Studies, Vol. 30 – No. 2; pages 150-151. Recovered by: [https://www.puttingourdifferencestowork.com/pdf/j.1467-9477.2007.00176%20Putnam%20Diversity.pdf].

The push for immigration is often driven by the desire for cheaper labor. Mainstream Republican politicians, despite presenting themselves as tough on immigration, often specify that they are primarily concerned with illegal immigration. However, both legal and illegal immigration have similar effects on the economy and, more importantly, on the nation as a whole. Even Donald Trump, who emphasized stricter immigration policies, expressed willingness to allow more immigrants as long as they entered legally. George J. Borjas explores this topic in his book We Wanted Workers. Borjas's research, outlined in his paper Immigration and The American Worker, reveals that only 2% (equivalent to 35 billion dollars) of the money immigrants contribute to the GDP is redistributed to native-born citizens. This means that the "immigration surplus" accounts for only about 0.2% of the total GDP. Borjas concludes that:

“Even though the overall net impact on natives is small, this does not mean that the wage losses suffered by some natives or the income gains accruing to other natives are not substantial. Some groups of workers face a great deal of competition from immigrants. These workers are primarily, but by no means exclusively, at the bottom end of the skill distribution, doing lowwage jobs that require modest levels of education. Such workers make up a significant share of the nation’s working poor. The biggest winners from immigration are owners of businesses that employ a lot of immigrant labor and other users of immigrant labor. The other big winners are the immigrants themselves.”

—Borjas, George J. (2013). Immigration and The American Worker. Washington DC: Center for Immigration workers; page 3. Recovered by: [https://cis.org/sites/cis.org/files/borjas-economics.pdf].

In his book We Wanted Workers, Borjas, along with numerous other studies, made the following assertion:

“The most credible evidence based solely on the data—suggests that a 10 percent increase in the size of a skill group probably reduces the wage of that group by at least 3 percent.”

—Borjas, George J. (2016). We Wanted Workers: Unraveling the Immigration Narrative. New York: Norton & Company, Inc; page 129.

As mentioned earlier, immigration can lead to a decrease in social trust within society, and this impact can also be felt in the workplace. In this study, Workers of The World Unite (or Not?), found that:

“Behavioral adaptations (also described as behavioral immune system) basically consist of a number of ancestrally adaptive attitudes, social values and norms towards out-group and in-group members, unwillingness to interact with out-group people and prejudice against people perceived as unhealthy, contaminated or unclean.7 In other words, human communities developed a set of cultural norms and social values aiming to be protected by infectious diseases (see e.g. Fincher and Thornhill, 2014 for more details on this). Since contemporary cultural values are affected -at least in part- by the behavioral immune system developed by local communities over the centuries, we expect regions that are located in more lethal disease environments to be characterized by more collectivistic norms (i.e. in-group favoritism, stronger family ties etc) even nowadays.”

—Benosa, Nikos; Kammasb, Pantelis (2018). Workers of the world unite (or not?). The effect of ethnic diversity on the participation in trade unions. MPRA Paper No. 84880; page 6. Recovered by: [https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/84880/1/MPRA_paper_84880.pdf].

This empirical data is also exploited by large companies. In April 2020, it was discovered that Amazon was able to assess the risk of unionization within its stores based on their level of diversity. This sheds light on why capitalists often support immigration. They benefit from the availability of cheap labor, while workers bear the cost of devalued labor due to increased supply in the labor market. Moreover, companies with more diverse workforces are less likely to unionize, which provides an incentive for companies to prioritize diversity in order to mitigate the risk of wage increases. Considering these factors, it becomes clear why the American Socialist Congress of 1910 adopted the following resolution:

“The Socialist party of the United States favors all legislative measures tending to prevent the immigration of strike breakers and contract laborers, and the mass importation of workers from foreign countries, brought about by the employing classes for the purpose of weakening the organization of American labor and of lowering the standard of life of the American workers.”

—Delegates to the 1910 “Congress” of the Socialist party of America, May 15-21, 1910; Chicago Illinois

One can observe the shipping of jobs to foreign markets as another pertinent example. In this case, let's focus on the trade relationship between the USA and China. The trade dynamics with China have resulted in the loss of numerous jobs in the USA, particularly in the manufacturing sector. This situation exemplifies a scenario where one class advances itself at the expense of the nation and the lower classes. The trade relationship with China leads to significant job displacements, primarily in manufacturing, which subsequently drives down wages. While it may benefit certain US industries, the overall impact is predominantly negative. Capitalists, driven by the pursuit of increased profits, utilize strategies such as immigration and globalization, as mentioned earlier, to further their objectives. This trend may be detrimental to American workers, but it is considered advantageous for wealthy Anglo-American Jewish capitalists.

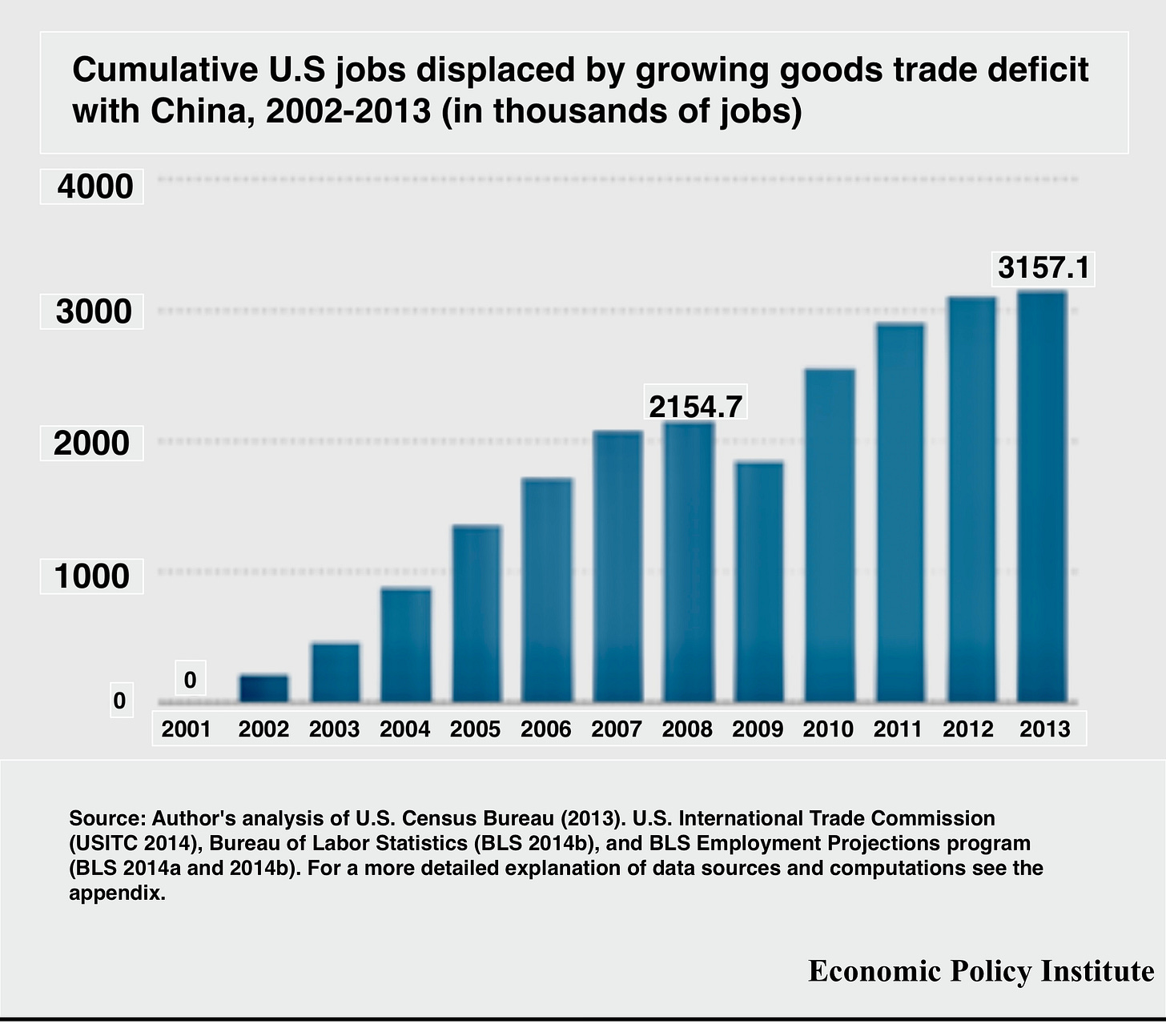

The growth of the US goods trade deficit with China from 2001 to 2013 has had a significant impact on the job market. It is estimated that this trade deficit led to the elimination or displacement of 3.2 million US jobs during that period. Out of these jobs, approximately 2.4 million (or three-fourths) were in the manufacturing sector. These lost manufacturing jobs represent around two-thirds of all US manufacturing jobs that were lost or displaced between December 2001 and December 2013.

“The 3.2 million U.S. jobs lost or displaced by the goods trade deficit with China between 2001 and 2013 were distributed among all 50 states and the District of Columbia, with the biggest net losses occurring in California (564,200 jobs), Texas (304,700), New York (179,200), Illinois (132,500), Pennsylvania (122,600), North Carolina (119,600), Florida (115,700), Ohio (106,400), Massachusetts (97,200), and Georgia (93,700). In percentage terms, the jobs lost or displaced due to the growing goods trade deficit with China in the 10 hardest-hit states ranged from 2.44 percent to 3.67 percent of the total state employment: Oregon (62,700 jobs lost or displaced, equal to 3.67 percent of total state employment), California (564,200 jobs, 3.43 percent), New Hampshire (22,700 jobs, 3.31 percent), Minnesota (83,300 jobs, 3.05 percent), Massachusetts (97,200 jobs, 2.96 percent), North Carolina (119,600 jobs, 2.85 percent), Texas (304,700 jobs, 2.66 percent), Rhode Island (13,200 jobs, 2.58 percent), Vermont (8,200 jobs, 2.51 percent), and Idaho (16,700 jobs, 2.44 percent).”

—Kimball, Will; Scott, Robert E. (2014). China Trade, Outsourcing and Jobs: Growing U.S. trade deficit with China cost 3.2 million jobs between 2001 and 2013, with job losses in every state. Economic Policy Institute. Recovered by: [https://www.epi.org/publication/china-trade-outsourcing-and-jobs/].

The job displacement estimates provided in this study are considered to be conservative. They only take into account the jobs directly or indirectly displaced by trade and do not include jobs in domestic wholesale and retail trade or advertising. Furthermore, these estimates do not fully account for the impact of job displacement on wages and consumer spending during the Great Recession of 2007-2009 and its aftermath. The reduction in wages and spending resulting from jobs displaced by China trade likely contributed to further job losses in the economy.

“Further, the jobs impact of the U.S. trade deficit with China is not limited to job loss and displacement and the associated direct wages losses. Competition with low-wage workers from less-developed countries such as China has driven down wages for workers in U.S. manufacturing and reduced the wages and bargaining power of similar, non-college-educated workers throughout the economy, as previous EPI research has shown. The affected population includes essentially all workers with less than a four-year college degree—roughly 70 percent of the workforce, or about 100 million workers”.

—Kimball, Will; Scott, Robert E. (2014). China Trade, Outsourcing and Jobs: Growing U.S. trade deficit with China cost 3.2 million jobs between 2001 and 2013, with job losses in every state. Economic Policy Institute. Recovered by: [https://www.epi.org/publication/china-trade-outsourcing-and-jobs/].

“As earlier EPI research has shown, trade with China between 2001 and 2011 displaced 2.7 million workers, who suffered a direct loss of $37.0 billion in reduced wages alone in 2011. The nation’s 100 million non-college-educated workers suffered a total loss of roughly $180 billion due to increased trade with low-wage countries (Bivens 2013). These indirect wage losses were nearly five times greater than the direct losses suffered by workers displaced by China trade, and the pool of affected workers was nearly 40 times larger (100 million non-college-educated workers versus 2.7 million displaced workers).”

—Kimball, Will; Scott, Robert E. (2014). China Trade, Outsourcing and Jobs: Growing U.S. trade deficit with China cost 3.2 million jobs between 2001 and 2013, with job losses in every state. Economic Policy Institute. Recovered by: [https://www.epi.org/publication/china-trade-outsourcing-and-jobs/].

Yes, this supports some US jobs. However, the overall net impact here is extremely negative:

“As shown in the bottom half of Table 1, U.S. exports to China in 2001 supported 161,400 jobs, but U.S. imports displaced production that would have supported 1,127,700 jobs. Therefore, the $84.1 billion trade deficit in 2001 displaced 966,300 jobs in that year. Net job displacement rose to 3,121,000 jobs in 2008 and 4,123,400 jobs in 2013.”

—Kimball, Will; Scott, Robert E. (2014). China Trade, Outsourcing and Jobs: Growing U.S. trade deficit with China cost 3.2 million jobs between 2001 and 2013, with job losses in every state. Economic Policy Institute. Recovered by: [https://www.epi.org/publication/china-trade-outsourcing-and-jobs/].

One of the most significant missteps made by America was the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). NAFTA, a free trade and investment agreement, offered investors a distinctive set of assurances aimed at encouraging foreign direct investment and the relocation of factories within the North American region, particularly from the United States to Canada and Mexico. Economist Robert E. Scott, in his paper titled The High Price of 'Free' Trade, stated:

“Since the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was signed in 1993, the rise in the U.S. trade deficit with Canada and Mexico through 2002 has caused the displacement of production that supported 879,280 U.S. jobs. Most of those lost jobs were high-wage positions in manufacturing industries. The loss of these jobs is just the most visible tip of NAFTA’s impact on the U.S. economy. In fact, NAFTA has also contributed to rising income inequality, suppressed real wages for production workers, weakened workers’ collective bargaining powers and ability to organize unions, and reduced fringe benefits.”

—Scott, Robert E. (2003) The High Price of ‘Free’ Trade. Economic Policy Institute. Recovered by [https://www.epi.org/publication/briefingpapers_bp147/].

“The effects of growing U.S. trade and trade deficits on wages goes beyond just those workers exposed directly to foreign competition. As the trade deficit limits jobs in the manufacturing sector, the new supply of workers to the service sector (from displaced workers plus young workers not able to find manufacturing jobs) depresses the wages of those already holding service jobs.”

—Scott, Robert E. (2003) The High Price of ‘Free’ Trade. Economic Policy Institute. Recovered by [https://www.epi.org/publication/briefingpapers_bp147/].

Free trade has had a detrimental impact on America's manufacturing industry, leading to a significant decline in manufacturing jobs over the years. In 1960, manufacturing jobs accounted for 28% of total employment in the US. However, by 2017, this percentage had dropped to only 8%, and it is projected to further decline to around 6.9% by 2026. The decline in manufacturing jobs has had profound consequences, as it was a source of good-paying employment for lower-skilled individuals, enabling families to thrive. Liberal trade policies that have contributed to a rising trade deficit have suppressed wages for lower-skilled workers and resulted in job displacements, thereby eroding the middle class and traditional family structures. There are even influential figures like Peter Thiel, a billionaire venture capitalist, who advocate for these policies. Thiel calls for the government to transfer key functions traditionally associated with the state to corporations, effectively shrinking the role of the state while expanding corporate power. This trend is accompanied by a push towards deracination in society. Moreover, when problems arise, the blame is often shifted to the government, absolving big businesses of responsibility.

This illustrates the ultimate goal of capitalism, which is to create a fragmented, anti-cultural society where individuals are constantly sold corporate products while toiling away in the economy to pay for various subscription services. This echoes the sentiment expressed by the World Economic Forum, stating, "You'll own nothing. And you'll be happy. What you want you'll rent, and it'll be delivered by drone." It is worth noting that Thiel is closely associated with Curtis Yarvin (Mencius Moldbug), who advocates for Neo-Reactionary (NRx) ideas that align with Thiel's objectives. The NRx movement seeks to establish corporate dominance in society, transforming companies into quasi-kingdoms where they have unchecked power. In this vision, key functions of the state are handed over to corporations, granting them significant power and influence without any accountability. Contrary to the notion that "fascism is capitalism in decay," as some may argue, prominent NRx thinker Nick Land states that "fascism is a mass anti-capitalist movement." The NRx movement represents the culmination of materialist ideologies, envisioning a stateless society where people are indistinguishable, enabling corporations to maximize profits by selling cheap products. This aligns with the views expressed by Klaus Schwab, the founder of the World Economic Forum.

“‘Stakeholder capitalism,’ a model I first proposed a half-century ago, positions private corporations as trustees of society, and is clearly the best response to today’s social and environmental challenges.”

“Business leaders now have an incredible opportunity. By giving stakeholder capitalism concrete meaning, they can move beyond their legal obligations and uphold their duty to society. They can bring the world closer to achieving shared goals, such as those outlined in the Paris climate agreement and the United Nations Sustainable Development Agenda. If they really want to leave their mark on the world, there is no alternative.“

—Schwab, Klaus (2020). What Kind of Capitalism Do We Want? Recovered by: [https://time.com/5742066/klaus-schwab-stakeholder-capitalism-davos/].

3. The Problem of Marxism

While few corporatists would identify themselves as "materialists," there have been some individuals like Gustavo Bueno in Spain who could be considered corporatists and have used the term. However, Marxism, despite being built on the concept of "materialism," is not truly materialistic. Marxism is a humanistic moral philosophy centered around the idea of class struggle, which makes it fundamentally incompatible with any form of corporatism. Bolshevism seeks not only class warfare and the dissolution of the nation but ultimately the abolition of the state as well. As a result, it is not compatible with nationalism or corporatism. The strength of Marxism lies in its ethical framework and principles as derived from Marx's teachings.

"Does not socialism contain the highest morality, anti-egoism, self-sacrifice, philanthropy?”

—Gentile, Giovanni (1899/1937). The Philosophy of Marx. Vitale, Caterina and Simpson, Shandon; Antelope Hill edition, 2022; page 27.

However, Marxism's revolutionary nature provides it with ethical grounding as it seeks to bring about social and economic justice through revolutionary action. Though Marxism may not explicitly outline a comprehensive ethical framework, its principles and goals inherently carry ethical implications. Without the revolutionary aspect, Marxism would lack the drive to challenge existing power structures and advocate for a more equitable society. Critics of Marx often overlook this aspect. Some argue that Marxism fails at materialism due to its promotion of violent revolution. However, it is important to understand that Marxism sees violence as a means to achieve the desired social transformation rather than an end in itself.

"We, the ‘revolutionaries,' are profiting more by lawful than by unlawful and revolutionary means.”

—Sombart, Werner (1909). Socialism and The Social Movement. London/New York: J. M. Dent & Co/ E. P. Dutton & Co, 1968; page 68.

It is often argued that the concept of the dictatorship of the proletariat is absurd or impractical in democratic countries. However, Friedrich Engels, in his introduction to The Class Struggles in France, underwent a change in his views, possibly shared by Marx as well. This serves to reinforce the point that both Marx and Engels had ethical goals, namely the establishment of socialism. The notion of "materialism" is employed to provide a practical direction and create the illusion of a solid justification. The issue does not lie in the impracticality of specific methods to achieve socialism, but rather in the contradiction faced by Marxism itself when it assumes a revolutionary and socialist stance.

If Marxism were genuinely materialist, it would act as a passive observer and predictor, refraining from advocating for any revolution. However, because it actively promotes revolution, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy that fails to fulfill itself completely. Marx, in comparison to the utopian and anarchist socialists he refuted, is perceived as more of a phantom, revealing his philosophical shortcomings in contrast to figures like Proudhon. Additionally, Marx's ideas lack the grounding found in the sometimes cloudy and occasionally eccentric predictions of Fourier. This observation has been made by other Marxists who acknowledge the projection of ethical principles related to class struggle within Marxism.

“But is there such a thing as communist ethics? Is there such a thing as communist morality? Of course, there is. It is often made to appear that we have no ethics of our own; and very often the bourgeoisie accuse us communists of rejecting all ethics. This is a method of shuffling concepts, of throwing dust in the eyes of the workers and peasants. [...]

In the sense in which it is preached by the bourgeoisie, who derived ethics from God's commandments. We, of course, say that we do not believe in God, and that we know perfectly well that the clergy, the landlords and the bourgeoisie spoke in the name of God in pursuit of their own interests as exploiters. Or instead of deriving ethics from the commandments of morality, from the commandments of God, they derived them from idealist or semi-idealist phrases, which always amounted to something very similar to God's commandments.

We reject all morality based on extra-human and extraclass concepts. We say that it is a deception, a fraud, a befogging of the minds of the workers and peasants in the interests of the landlords and capitalists.

We say that our morality is entirely subordinated to the interests of the class struggle of the proletariat. Our morality is derived from the interests of the class struggle of the proletariat [...].”

—Lenin, Vladimir (1920). Tasks of The Youth Leagues. Peking: Foreign Language Press, 1975; pages 10-11.

The concept of "materialism" in Marxism can be more accurately described as a strategic tool of weaponized nihilism disguised under the guise of historical determinism. While the term "economic determinism" may be somewhat misleading, it is true that Marx often discusses processes in which actions driven by specific economic priorities give rise to new situations that generate fresh economic concerns. However, as Richard W. Miller points out, political phenomena are integral to Marx's perspectives. What does this imply? It implies that Marx cannot be considered a nihilist, which would align more closely with pure materialism. Marx and Marxists uphold a consequentialist moral framework rooted in class struggle, but they criticize their opponents for being excessively moralistic.

“In a very broad sense, Marx is a moralist, and sometimes a stern one: he offers a rationale for conduct that sometimes requires self-sacrifice in the interests of others. [...]

At the same time, Marx often explicitly attacks morality and fundamental moral notions. He accepts the charge that ‘Communism [...] abolishes [...] all morality, instead of constituting [it] on a new basis.' The materialist theory of ideology is supposed to have ‘shattered the basis of all morality, whether the morality of asceticism or of enjoyment.' Talk of 'equal right' and 'fair distribution' is, he says, 'a crime,' forcing 'on our Party’ [...] obsolete verbal rubbish [...] ideological nonsense about right and other trash so common among the democrats and French Socialists.”

—Miller, Richard W. (1984). Analyzing Marx: Morality, Power and History. New Jersey: Princeton University Press; page 15.

Miller correctly highlights that the claim that Marx was a moralist mainly stems from the language he employs rather than the theory itself. As Miller observes, Marx puts forth principles meant to guide present-day social and political choices, effectively constituting a political morality for a significant audience. This does not amount to a replacement of morality, as Miller suggests and as Marx intends. Instead, it represents a consequentialist morality grounded in the interests of a specific class, while simultaneously serving as a tactical weaponized nihilism veiled under the guise of historical determinism. If this outcome is deemed inevitable, arising from the exploitation and contradictions of capitalism, and if moral judgments cannot be made, then there is no reason for it to engage in anti-nationalist revolutionary praxis, unless its purpose is to fulfill itself predictably.

Interestingly, Marx even criticizes those who align with his goal of improving the conditions of the proletariat. For instance, he views the views of figures like Mikhail Bakunin as utopian and excessively moralistic. In The Poverty of Philosophy, Marx takes issue with Proudhon solely for believing in the concepts of good and bad. He attempts to defend American slavery as a means to illustrate a problem with Proudhon's viewpoint. However, it is important to note that even if Marx's argument were correct, slavery could still be argued as morally reprehensible, just as Proudhon does with the state. Marx employs the attack on someone's moral stance as a tactical weaponized nihilism but does not subject his own views to the same scrutiny. This pattern is also evident in his critique of Hegel's usage of the concept of "right."

Marxism conceals its moral character behind the mask of historical determinism. It borrows and adapts Hegel's dialectic of master and slave, as seen in works like Phenomenology of Spirit and Encyclopedia. In the Paris Manuscripts, Marx even claims that the "Phenomenology" contains the fundamental elements of revolution. According to Marx, the oppression of the proletariat by the bourgeoisie renders communism inevitable. Echoing Hegel's perspective, as stated in his "Encyclopedia" (§435), the slave eventually surpasses the master. Similarly, Marx argues that the proletariat, once it achieves heightened self-awareness, will undergo the same transformation.

“The full unfolding of conflictuality corresponds, in Hegelian terms, with the dialectical figure of the Servant and Master found in the Phenomenology of Spirit. The bourgeoisie gives work to the proletariat and, at the same time, makes a living of such work; through the latter, the proletarian Servant attains consciousness of himself and of his condition and can act in view of the transcendence of the socio-political order. He can constitute himself as a class an sich und für sich, in-itself and for-itself, as a class that effectively is and knows of being so. The attainment of consciousness may only be given within the conflict, and only because of it; and this according to the idealistic theme of the identity between being and knowing, Which is identified as class consciousness, so that, as highlighted by Gramsci, a worker is proletarian when he knows of being so and when he operates according to this awareness.”

—Fusaro, Diego (2018). Hegel and the Primacy of Politics: Taming the Wild Beast of the Market. London: Pertinent Press; pages 154-155.

Marx posits that communism represents the ultimate stage of human societal organization, but interestingly, capitalism shares a similar belief. Both ideologies view themselves as the culmination of historical progress, representing the "end of History" in their respective worldviews. However, it is worth noting that there are notable distinctions between them. Marxist variations of socialism can be seen as having certain capitalistic elements, as they do not seek to entirely replace the values associated with monetary exchange but rather aspire to possess and control them. One example of this can be observed in Marx's discussion of Free Trade, where he acknowledges its significance.

“Generally speaking, the protectionist system today is conservative, whereas the Free Trade system has a destructive effect. It destroys the former nationalities and renders the contrast between proletariat and bourgeois more acute. In a word, the Free Trade system is precipitating the social revolution. And only in this revolutionary sense do I vote for Free Trade.”

—Engels, Friedrich (1888). On The Question of Free Trade. Preface for the 1888 English edition pamphlet. Recovered by: [https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1888/free-trade/#:~:text=The%20question%20of%20Free%20Trade%20or%20Protection%20moves%20entirely%20within,do%20away%20with%20that%20system]

Individuals who identify as conservatives but advocate for free trade may find it intriguing to delve into why Marx supported and characterized it as both "destructive" and "revolutionary." Marx viewed free trade as an essential component of the dialectical process that imposes uniformity on a global scale, mirroring the ultimate goal of communism. Marx condemned opposition to this process as "reactionary," believing that constant revolutionizing of the means of production was an inevitable aspect of capitalism. This perpetual state of change created an atmosphere of ongoing uncertainty and agitation that set the "bourgeoisie epoch" apart from preceding eras.

The imperative for a continuously expanding market propelled capitalism's global expansion, resulting in a "cosmopolitan character" shaping modes of production and consumption in every country. Within Marxist dialectics, this globalization process is a necessary step in eradicating national boundaries and distinct cultures, laying the groundwork for world socialism. It is capitalism that establishes the foundation for internationalism. Thus, it becomes evident that the ethics of class struggle inherent in Marxism inherently oppose nationalism. This fact alone should suffice to illustrate the contradiction within Marxist ethics. Even syndicalists, before their transformation into fascists, held anti-national sentiments due to their belief in class warfare.

“The first thing that must disappear is the State, which is the most outstanding representative of non-productive, parasitic Society”

—Berth, Édouard (1908). Anarchism and Syndicalism. Recovered by: [https://libcom.org/article/anarchism-and-syndicalism-edouard-berth].

Moreover, it is evident that Marxists and other proponents of class struggle actively criticize and undermine national sentiments:

“Today it is notorious that revolutionary patriotism is dead; something else has arisen to take its place, a new feeling: the class idea which has replaced the idea of the fatherland, defining the split between the people on the one side and the State and democracy on the other. For with the appearance of revolutionary syndicalism a strange opposition has arisen between democracy and socialism, between the citizen and the producer, an opposition that has assumed its crudest as well as its most abstract form in the resolute rejection of the idea of the fatherland, which is identified with the idea of the State. And the strikes, which are becoming increasingly more powerful, more widespread and more frequent, are revealing to a surprised world the collective power of the workers, who are becoming more class conscious and more self-controlled with each passing day.”

—Berth, Édouard (1908). Anarchism and Syndicalism. Recovered by: [https://libcom.org/article/anarchism-and-syndicalism-edouard-berth].

The concept of worker self-governance, in addition to being anti-nationalistic, presents another significant challenge in the form of anarchism. Despite some of the old syndicalists, apart from Georges Sorel, expressing hostility towards anarchism (to the extent of disputing Proudhon's classification as an anarchist), it is functionally indistinguishable from anarchism, as highlighted by Werner Sombart. Giovanni Gentile also remarks on the syndicalist perspective opposing the state:

“[...] opposing liberal individualism, which it has considered abstract and therefore unreal. Alternatively, one might consider pure Syndicalism. But pure Syndicalism is not the syndicalism of obligatory syndicates — whose very legal recognition implies a principle of obligation to an entity superior to the syndicates, that is to say to a State to which the syndicates would be subordinate. That relationship would contradict the central principle of pure Syndicalism which does not recognize any legitimate power external to the spontaneous and free syndicate. Pure Syndicalism prefers the de facto syndicate to the legally recognized syndicate. Pure Syndicalism aspires to absorb the State in itself. In the spontaneous and inevitably fragmentary character and multiplicity of the syndicates, essential unity would be destroyed. Pure Syndicalism is an ideal alternative that is antithetical to the most profound principles and inspirations of the Fascist State.”

—Gentile, Giovanni (2002). Origins and Doctrine of Fascism. New Jersey: Transaction Publishers; pages 71-72.

Nationalism, syndicalism, corporatism, and Marxism all share a common objective of improving the conditions of the working class. However, proponents of class warfare, including Marxists, tend to rely on flawed or incomplete data when refuting opposing viewpoints. They often argue that anyone not aligning with their anti-nationalist stance must be against the proletariat. For example, they might highlight the 1927 election in New South Wales, Australia, where Labor party candidate Jack Lang lost to Thomas Bavin of the Nationalist Party. Bavin implemented austerity measures during an economic depression, leading to violent clashes between striking workers and the police. However, Lang was eventually reelected in 1930.

From the perspective of class warfare proponents, Lang may not be their ideal candidate since he was anti-communist and later formed the Non-Communist Australian Labor Party. Nevertheless, he was still considered a better option compared to Bavin, unless one adheres to accelerationist beliefs. Examining the history of the Nationalist Party reveals its origins in the Labor Party following the 1916 Labor split over World War I. The Nationalist Party formed through a merger between the National Labor Party and the Commonwealth Liberal Party. In Australia, it is worth noting that Australian socialism, anarchism, and communism included individuals who, despite being anti-nationalists, held racist views. The White Australia Policy in the early 1900s received support from socialists and anarchists who exhibited racist tendencies. For instance, William Lane advocated for a stateless society but also supported the White Australia Policy and wrote about an impending race war with the Chinese. Additionally, there were instances where individuals like Arthur Desmond, initially an anti-racist socialist politician in New Zealand, became highly anti-Semitic after moving to New South Wales.

While this example may not be exhaustive, it underscores the importance of conducting a thorough analysis when responding to attacks on corporatism. These movements share a proletarian nature while also embracing nationalism. Their goal is not solely to "eat the rich" but rather to achieve a synchronization of all classes and the economy through Gleichshaltung (synchronization). Fascism, for instance, originated from syndicalist labor movements in France and Italy. Nationalism itself, as noted by Weber, has roots in the Jacobins. When socialists in France and Italy adopted militant nationalism, they rejected class warfare as it contradicted the nationalist ethic of national unity and harmony. Gentile and Weber accurately highlight the paradoxical nature of nationalists defending capitalism.

"Because Nationalism had been the first to challenge property rights for the sake of a superior interest.”

—Weber, Eugen (1964). Varieties of Fascism: Doctrines of Revolution in the Twentieth Century. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company; page 24.

“Men like Maurice Barrès in France described themselves as National Socialist. They realized that national unity implied social justice, that national power implied the planned use of national resources, and that national harmony might mean the equalization or the redistribution of wealth and opportunity and economic power. Yet, they did not feel the need to maintain the established order at all costs. Putting the nation first and property second, they found their theories were leading them toward Jacobinism — even while the official left-wing heirs of Jacobins were moving in the opposite direction.”

—Weber, Eugen (1964). Varieties of Fascism: Doctrines of Revolution in the Twentieth Century. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company; page 25.

The nationalist and corporatist perspective prioritizes unity, harmony, and the progress of the nation's people. Nationalism, similar to corporatism, aims to advance the interests of the nation and its workforce. Unlike capital, labor is not inherently opposed to nationalism as it represents the working class within the nation. The opposition arises when labor is exploited for class conflicts, as advocated by Marxism, which seeks a global proletarian revolution. However, Marxists mistakenly perceive the proletariat as a universal entity. Those who adhere to Marxist ideologies and non-Marxist proponents of class warfare often view our movement as actively undermining the well-being of the proletariat or as a movement that cynically adopts proletarian rhetoric solely to thwart their international revolution. Consequently, they put forth the following claims:

"It is precisely the attempt to maintain the capitalist system which leads under modern conditions with fatal precision to the resort to Fascism.”

—Muste, A. J. (1935). A Reply to Liberal Critics of Bolshevism. The Position of the Workers Party on Proletarian Dictatorship and Worker’s Democracy in Light of Recent Events. New Militant, Vol. I No. 28, 6 July 1935, p. 4. Recovered by: [https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/muste/1935/07/reply1.htm].

Now to highlight fundamental flaws in Marxist economics. Marx himself equated Socialism with Communism, while Lenin, in The State and Revolution, established the distinction that Socialism is the lower phase of Communism. Marx also argued in Critique of The Gotha Program that this lower phase of communism would be characterized by the absence of the value form of commodity production. However, in practice, Marxist experiments have still exhibited the presence of commodity production. Another crucial aspect of communism, including its lower phase of socialism, is the absence of a state and social classes. This implies that so-called socialist countries are merely in a transitional period towards socialism. Furthermore, the proletarian dictatorship seizes state power and converts the means of production into collective property, but in doing so, it abolishes itself as a class and eliminates all class distinctions. This poses a challenge for Marxists who wish to label their proletarian states as socialist in the Marxist sense, despite acknowledging their statehood and class distinctions.

“As I was coming in through your hall just now, I saw a placard with this inscription: “The reign of the workers and peasants will last forever.” When I read this odd placard, which, it is true, was not up in the usual place, but stood in a corner-perhaps it had occurred to someone that it was not very apt and he had moved it out of the way when I read this strange placard, I thought to myself: there you have some of the fundamental and elementary things we are still confused about. Indeed, if the reign of the workers and peasants would last forever, we should never have socialism, for it implies the abolition of classes; and as long as there are workers and peasants, there will be different classes and, therefore, no full socialism.”

—Lenin, Vladimir. All-Russia Congress of Transport Workers, May 27th 1921

“The state is withering away insofar as there are no longer any capitalists, any classes, and, consequently, no class can be suppressed.”

—Lenin, Vladimir (1918). The State and Revolution. Lenin Internet Archive, Recovered by: [https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/staterev/ch05.htm].

“Socialism means the abolition of classes. The dictatorship of the proletariat has done all it could to abolish classes. But classes cannot be abolished at one stroke.

And classes still remain and will remain in the era of the dictatorship of the proletariat. The dictatorship will become unnecessary when classes disappear. Without the dictatorship of the proletariat they will not disappear.”

—Lenin, Vladimir (1919). Economics And Politics In The Era Of The Dictatorship Of The Proletariat. Lenin Internet Archive, Recovered by: [https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1919/oct/30.htm].

Lenin indeed implied that the state would wither away once class distinctions ceased to exist. However, in practice, the state has not withered away as anticipated. According to Marxism, the existence of a state machinery or state functions implies that the state should only serve administrative purposes and lack the capacity to enforce class rule. It would be a mere skeleton of its former self, with institutions primarily focused on monitoring production while labor vouchers are still in use. This understanding suggests that countries like the USSR were in a transitional phase towards socialism rather than actual socialism, as they did not meet Marx, Engels, and Lenin's criteria for socialism. Therefore, when Marxists label fascist states as capitalist, it carries little weight since their own countries did not meet their own standards of socialism. The distinction between State Socialism and State Capitalism is essentially meaningless. The claims that capitalists ruled Nazi Germany can be refuted by examining Anton Pannekoek's work, State Capitalism and Dictatorship. Additionally, both Vladimir Lenin in The Tax In Kind pamphlet and Mao Zedong in 1953 referred to "State Capitalism" as interchangeable with "State Socialism."

A. James Gregor argued this and in his book Italian Fascism and Developmental Dictatorship. Fascism, in Gregor's analysis, mobilized itself through an economic developmental program that aimed at gradual socialization. Fascist regimes like Italy perceived their economies as underdeveloped, with a proletariat lacking the technical competence and consciousness necessary for fulfilling developmental tasks. Similarly, Lenin acknowledged the backwardness of Russia in his essay The Immediate Tasks of The Soviet Government. As a result, a form of corporatism briefly emerged within the Soviet Union's State Capitalist New Economic Policy as a means to catch up with industrialized Western nations.

“The Soviets had made a similar move in the 1920s. Faced with a scarcity of administrative personnel, the state encouraged enterprises to combine into trusts and trusts to combine into syndicates. These large units continued into the 1930s where they were utilized to bridge the gap between overall plans and actual production.”

—Temin, Peter (1990). Soviet and Nazi Economic Planning in the 1930’s. Massachusetts: Massachusetts Institute of Technology; page 18.

Lenin recognized that advancing society in a developmental direction would require the implementation of what he referred to as "sharp forms of dictatorship." He also acknowledged that the entrepreneurial bourgeoisie would be compelled to collaborate with the Soviet state. This parallel between Lenin's approach and Fascism's adoption of class collaborationism is evident. This departure from Marxism is significant, as it deviates from Marxist principles.

“Both Lenin and Mao Zedong mention it in their early works and according to Mao the United Fronts operational principle is to unite with secondary enemies against the principal enemy. By means of the united front the CCP won The revolutionary war and the front remained an important tool for maintaining regime stability after the CCP seized power. The CCP used the united front concept to reach out to so-called democratic parties and prominent individuals outside the party allowing it to collaborate with the broadest possible range of social classes thereby strengthening its total social control.”

—Liao, Xingmiu; Tsai, Wen-Hsuan (2019) The United Front Model of Pairing-Up in The Xi Jinping Era. The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Recovered by [https://www.jstor.org/stable/26603249]

In Communist China, the concept of the United Front is utilized to facilitate "pairing-up" between local government officials and members of Democratic parties. This practice aims to promote collaboration and unified efforts in governance. It can be perceived as a form of class collaboration, with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) referring to it as "making friends." This approach embraces market-oriented principles, which provides a more accurate characterization of the CCP as a corporatist entity. Within its state organs, the CCP incorporates social organizations into the state apparatus, ensuring regime stability and survival. This can be understood as a form of "methodological relationism," where party cadres establish relationships with non-party individuals from the capitalist class. As a result, the CCP integrates private enterprises by establishing regional-level networks that are connected to the state trade union. This analysis reveals that corporatism, rather than Marxist socialism, is the dominant framework in the current CCP and was also evident in the USSR under the leadership of Lenin and later Leonid Brezhnev.

There is often an attempt to distinguish between State Capitalism and State Socialism, with the former involving the state ownership of the means of production and typically exhibiting more market activity than the latter. However, this distinction is superficial, as even so-called State Socialist countries had market activity. The goal of unified social planning, replacing commodity production and the value form, is often highlighted in State Socialism. However, financial accounting persisted in all planned economies, indicating remnants of the so-called anarchy of production, as a profit incentive still remained, as recognized by Joseph Stalin.

Another distinction made is that state capitalism involves wage labor, with the state becoming a new capitalist class, while State Socialism does not. However, it is important to note that the Soviet Union never abolished wage labor. In fact, the piece-rate system present in the USSR was even described by Marx in Das Kapital as one of the most bourgeois and capitalist forms of wages. Therefore, State Capitalism can be understood as the merging of bourgeois classes into the state through the process of nationalization, as articulated by Lenin. Mussolini claimed that if fascism followed natural economic development, it would:

“lead inexorably into state capitalism, which is nothing more nor less than state socialism turned on its head. In either event, [whether the outcome be state capitalism or state socialism] the result is the bureaucratization of the economic activities of the nation.”

—Mussolini, Benito; Address to the National Corporative Council, 14 November 1933. Fascism: Doctrine and Institutions. Fertig, 1978

Fundamentally, this indicates that the economic principles of Marxism were never fully put into practice. Instead, every Marxist experiment has resulted in a form of State Capitalism, which can be considered a non-Marxist variant of socialism. These regimes were compelled to adopt economic principles that leaned towards corporatism in order to maintain stability and achieve growth. The fact that such adaptations were necessary can be seen as a clear indication of the failure of Marxist economics. It is therefore understandable why some socialists, such as Werner Sombart, would ultimately abandon Marxism for a more national socialist program.

4. The Roots and Forms of Corporatism

Feudal Socialism

Some individuals associate corporatism with the "reactionary socialism" espoused by figures like Adam Müller and Leopold von Haller in Germany, as well as certain factions within the Tory Party and French Legitimists. The works of Müller and Haller remain untranslated, but their ideas can still be characterized as "reactionary" and "feudal," as labeled by Marx. These individuals sought to revive feudal guilds and had strong ties to the counter-enlightenment movement. Therefore, the term "reactionary" is fitting in describing their approach. Müller and Haller had different perspectives: Müller was a political romanticist, while Haller, as described by Sombart, was a materialist.

“When the economic differences first showed themselves, and in consequence, anti-Capitalist literature arose, no small part of it advocated that the Capitalist organization of society should be replaced by the organization which had preceded it. I am thinking of the writings of Adam Müller and Leopold von Haller in the first third of the nineteenth century. Men like these desired to see the medieval feudal system with its Craft guilds take the place of the Capitalist system. This point of view may still be met with, though in no wise so clearly and forcibly expressed as when it first appeared.”

—Sombart, Werner (1909). Socialism and The Social Movement. London/New York: J. M. Dent & Co/E. P. Dutton & Co, 1968; page 21.

Christendom and Roman Catholicism

Corporatism has historical connections to Christianity dating back to the time of St. Paul the Apostle, who expressed ideas that could be interpreted in relation to corporatism.

“[12] For as the body is one, and hath many members; and all the members of the body, whereas they are many, yet are one body, so also is Christ. [13] For in one Spirit were we all baptized into one body, whether Jews or Gentiles, whether bond or free; and in one Spirit we have all been made to drink. [14] For the body also is not one member, but many. [15] If the foot should say, because I am not the hand, I am not of the body; is it therefore not of the body?

[16]!And if the ear should say, because I am not the eye, I am not of the body; is it therefore not of the body? [17] If the whole body were the eye, where would be the hearing? If the whole were hearing, where would be the smelling? [18] But now God hath set the members every one of them in the body as it hath pleased him. [19] And if they all were one member, where would be the body? [20] But now there are many members indeed, yet one body.

[21] And the eye cannot say to the hand: I need not thy help; nor again the head to the feet: I have no need of you. [22] Yea, much more those that seem to be the more feeble members of the body, are more necessary. [23] And such as we think to be the less honourable members of the body, about these we put more abundant honour; and those that are our uncomely parts, have more abundant comeliness. [24]”

— 1 Corinthians 12:12-23, Douay-Rheims Bible

The connection between Christianity and Corporatism has its roots in biblical teachings, an aspect that may have been overlooked by more contemporary, liberal forms of Christianity. In 1881, Pope Leo XIII aimed to broaden the comprehension of Corporatism and provide a more concrete understanding of its principles. Subsequently, in 1884, during a commission held in Freiburg, the declaration was made that Corporatism entailed:

“A system of social organization that has at its base the grouping of men according to the community of their natural interests and social functions, and as true and proper organs of the state they direct and coordinate labor and capital in matters of common interest.”

—Wiarda, Howard J. (1997). Corporatism and Comparative Politics: The Other Great "Ism". London/New York: M. E. Sharp, Inc., page 37.

Corporatism is characterized by economic tripartism, which involves negotiations between business, labor, and state interest groups to establish economic policies. Pope Leo XIII's influential work, Rerum Novarum: Rights and Duties of Capital and Labor, is considered one of the greatest philosophical works of the modern era. In this encyclical, Leo emphasizes the equal importance of employers and employees, advocating for their cooperation for the betterment of society. He stresses that employers have a duty to provide adequate wages and working conditions, while also recognizing the natural right to private property and ownership of industry, with the need for state intervention when necessary. It is essential to note that Leo condemns socialism and criticizes rampant capitalism, aiming to address and improve the working and economic conditions of workers without advocating for the destruction of class hierarchy or proletariat dominance over industry.

Pope Pius XI's Quadragesimo Anno (The Fortieth Year) takes a broader perspective, addressing society as a whole. This influential document received praise and admiration from politicians worldwide, including figures like Mussolini and Salazar. Quadragesimo Anno discusses the concept of tripartite Corporatism, a novel form at the time that divided society into three corporate groups: government, industry, and labor. This model was adopted by many corporate states of that era. While the modern church may differ from the days of Leo XIII and Pius XI, it is impossible to ignore the deep-rooted connection between Christianity and Corporatism, which is ingrained in the very foundation of the faith.

“It is well-established that Corporatism was not the invention of politics or socio-economic thinking in the aftermath of World War I. It came back into vogue throughout Europe in the 1920s, but actually had a long history behind it, and can be traced to the 19th century when certain currents of political Catholicism voiced their criticism of the liberal order and the legacy of the French Revolution. It was counter-revolutionary Catholic circles in France, Belgium, Austria, and Germany that sparked off the corporate idea, which was to build an organic society by reviving legally recognized trade-related bodies around which social order and harmony could be achieved. —Pollard 2017, p. 42-44

By way of reaction to the conflictual turn that the socio-economic order was taking and the need for a solution to class rivalry, part of Catholic culture harked back to the pre-revolutionary guild system. [...] In response to the social conflict engendered by liberal individualism and the capitalist economy, their idea was to revive solidarity between workers and entrepreneurs. Catholicism’s approach to the social question was conservative, anti-revolutionary, and paternalistic. —Vallauri, 1971, p. 15-18.