Ikki Kita: The Philosopher of Imperial Japan

by Zoltanous and Nahobino

Introduction

Japan is often associated with the atomic bomb, war crimes, and a once formidable military. However, the historical journey that led to these associations and the influential figures involved is frequently overlooked. One such figure is Ikki Kita, recognized as the "father of Japanese fascism," whose legacy is surrounded by controversy and misunderstanding. Kita remains one of the most polarizing figures in Japanese history. As a political thinker, he envisioned a dramatically restructured Japan that intertwined socialism, nationalism, Buddhism, and militarism. During the tumultuous early 20th century, Kita's writings served as a revolutionary blueprint, advocating for extensive land reforms, economic nationalization, and a 'Showa Restoration' to restore Japan's strength and unity. While his ideas attracted fervent loyalty among young military officers, they also incited significant controversy, ultimately leading to his execution. This article explores Kita's significant works, the ideologies they shaped, and their enduring impact on Japan's trajectory toward militarism and war.

Early Life and Influences

Kita was born in 1883 on the small island of Sado in Akita Prefecture, Japan, to a family of samurai and merchant heritage. Though his family was relatively modest, this background exposed him early to the challenges of rural Japan and the inequalities that the Meiji Restoration exacerbated. It also instilled in him a rebellious spirit. These experiences fueled his passion for addressing social injustices and the inequalities he perceived as corrupting Japanese society from within. Kita attended university but soon became disillusioned. A prolific reader, he educated himself through independent study and philosophical inquiry, particularly exploring socialism, Confucianism, and Western political thought. Influenced by Western philosophers like Plato, Rousseau, and Marx, as well as Japanese nationalists and reform-minded thinkers, Kita developed a unique perspective on social reform.

Promulgation of the new Japanese constitution by Emperor Meiji in 1889

His intellectual growth coincided with Japan's rapid modernization and industrialization during the Meiji Era when Japan was striving to catch up with the West after having their dignity humiliated by unequal treaties by the Western powers. While Japan's modernization was successful with rapid industrialization, it also introduced new challenges, such as income inequality, social tensions, and Western imperialist pressures. These issues reinforced Kita's belief that Japan needed a strong, centralized government to protect its interests against Western powers and care for its people through economic reforms. Adding to his unique worldview was his daily use of cocaine, a habit he developed to alleviate pain from a childhood injury. This addiction likely influenced his intense and sometimes radical perspectives on society and governance.

In September 1905, Kita returned to Tokyo from his hometown of Sado during the Hibiya Riots, which erupted in protest against the Treaty of Portsmouth. Negotiated by U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, the treaty ended the Russo-Japanese War. It included terms favorable to Japan's imperialist ambitions, granting international recognition of Japan's influence and control over parts of Russian-dominated China and Korea. This victory for Japan was the first significant victory a non-White race had against a major power, and it brought Japan from being an exploited nation like China into one that could sit at the bargaining table with the rest of the world powers.

Despite these gains, activist groups viewed the treaty as a humiliating failure, sparking widespread riots. While Kita shared the protesters' desire to enhance Japan's international prestige, he disagreed with their values concerning the Kokutai, which he believed was "a tool in the hands of the genro (oligarchy)." Amidst this backdrop, Kita wrote his first book, Kokutairon and Pure Socialism.

George Wilson summarizes the context:

"Kita wrote his first book against a background of widespread popular discontent over the outcome of the Russo-Japanese War."

— George Wilson, Radical Nationalist In Japan: Kita Ikki 1883-1937

The riots signified a rise in violent political uprisings in Japan, aligning with Kita's radical political ideology. Kokutairon was Kita's first politically motivated book, reflecting his early political views and affiliations. Danny Orbach describes this phase as Kita's "socialist, secular and rational phase." According to Oliviero Frattolillo, Kita was driven to write "Kokutairon" due to his intellectual peers' uncritical mindset.

Frattolillo notes:

"Kita was particularly critical of the submissive attitude of certain intellectuals towards the system, who obsequiously accepted the acquisition of new theories and new forms of knowledge from the West, translated and transplanted in Japan."

— Oliviero Frattolillo, Interwar Japan Beyond The West: The Search For a New Subjectivity In World History

Through his work, Kita aimed to critique society's flaws and propose a socialist alternative. Kita's second book, An Informal History of The Chinese Revolution, critically analyzes the 1911 Chinese Revolution. Drawn to the cause of the 1911 Chinese Revolution, Kita joined the Tongmenghui (United League) led by Song Jiaoren. He traveled to China intending to help overthrow the Qing dynasty, which he perceived as a puppet of Western powers. However, Kita also harbored an interest in revolutionary nationalism. The nationalist group Kokuryūkai (Amur River Association/Black Dragon Society), founded in 1901, shared his views on Russia and Korea, leading to him joining them. As a special member of the Kokuryūkai, Kita was sent to China to write for the organization and report on the ongoing situation during the 1911 Xinhai Revolution. By the time he returned to Japan in January 1920, Kita had become disillusioned with the Chinese Revolution and the strategies it offered for achieving the changes he envisioned during his time there; he saw Japan being represented in the same way or worse than the Western exploiters. He joined forces with Ōkawa Shūmei and others to establish the Yuzonsha (Society of Those Who Yet Remain), a nationalist and Pan-Asianist organization, dedicating his efforts to writing and political activism. Over time, he emerged as a leading theorist and philosopher of the nationalist movement in pre-World War II Japan.

The Empire of Japan experienced economic growth during World War I, but this prosperity ended in the early 1920s with the onset of the Shōwa financial crisis. Social unrest grew as society became increasingly polarized, with issues like the trafficking of girls becoming an economic necessity for some families due to poverty. Labor unions were increasingly influenced by syndicalism, communism, and anarchism, while Japan's industrial and financial leaders continued to amass wealth through close connections with politicians and bureaucrats. The military, perceived as "clean" from political corruption, had elements within it eager to take direct action to address what they saw as threats to Japan stemming from the weaknesses of liberal democracy and political corruption.

His final major political work was An Outline Plan For The Reorganization of Japan. Initially written in Shanghai but banned in 1919, it was published by Kaizōsha, the publisher of the magazine Kaizō, in 1923, only to be censored by the government. A common thread in his early and later political writings is the idea of a national policy (Kokutai), which he believed would help Japan navigate impending economic or international crises. He imagined Japan at the forefront of a united and liberated Asia, harmonizing global cultures by integrating Japanized and universalized Asian philosophies. This was aimed at paving the way for the rise of a singular superpower crucial for ensuring future world peace. A key aspect of this vision was the dismissal of liberal democracy and pan-Asianism.

Nationalism, Socialism, and Militarism

Kita’s ideology has been the subject of heated debate, with many elements from different sources blending into his unique and confusing ideology for onlookers. This has caused it to be mischaracterized and labeled with other fluid and unhelpful labels, such as far-right. Kita’s ideology often contradicted the prevailing ideas of his time and challenged the left-right political spectrum.

George Wilson elaborates on this by stating:

“It is my intention, however, that the complexity of Kita’s theory of revolution raises a question as to whether terms like right and left are really useful for classifying Japanese thinkers in the early 20th century. Left-right analysis originated in the French revolution and later spread to other Western nations serving to designate certain broad lines of political orientation: right signifies a desire to conserve existing institutions and strengthen traditional social ties, especially patriotism and family bonds, while left suggests a willingness to change into support, large-scale reform sponsored by government in the affairs of the people. The left is most commonly associated with lower-class support whereas upper-class interests back rightist causes. Both are ipso facto capable of transformation from moderate to extreme forms of belief and action in order to achieve their goals. Accepting these criteria is fairly typical assumptions about the political continuum, we may say—anticipating our conclusion—that Kita Ikki does not fit the standard picture of the right.“

— George Wilson, Radical Nationalist In Japan: Kita Ikki 1883-1937

Regarding Kita’s thoughts on the Kokutai, Kita's perspective was similar to that of the Jongxia, envisioning the emperor as a paternal, hopeful, and spiritual leader for everyone to unite behind. During that era in Japan, Emperor Meiji moved away from absolute rule and introduced constitutionalism, leading to the political concept of "kokutairon." This concept, formulated by Tatsukichi Minobe, positioned the liberal state, or kokutai as supreme, and even the emperor was only an “organ of the State” as defined through the constitutional structure, rather than a sacred power beyond the state itself. Minobe used the metaphor of the head of the human body to describe the role of the emperor. This thesis was influenced by German legal philosopher Georg Jellinek, whose work, General Theory of The State was published in 1900, and the British concept of a constitutional monarchy. Minobe warned that the Diet of Japan must carefully limit the emperor’s right of supreme command over the military if Japan did not end up with a dual government in which the military would become completely independent and above the rule of law, and unaccountable to civilian authority. This would eventually happen by the system he created when the Genro helped facilitate military power during the Taisho crisis in the government due to the lack of checks on the military by the emperor.

Ikki Kita disagreed with kokutairon, advocating for absolutism and a Platonic paternal monarchy and wishing to bring back the spirit of the Meiji Restoration with its absolute rule but free from the strings of the Genro and Zaibatsu and the false promises of the Western powers. The main point of divergence lies in his use of totalitarianism. Kita's understanding of totalitarianism was shaped by his extensive reading of Plato's Republic, which inspired him to emulate its ideas.

“Plato’s Republic was regarded by these Japanese Radicals as having provided the foundational Basis of western socialist and communist ideologies. The text increasingly was thus conceived as the blueprint for social revolution…”

– Hyun Jin Kim, Plato In East Asia?

Another central element of Kita's philosophy was his critique of Japan's ruling elites, whom he saw as corrupt and out of touch with the general population. He criticized the zaibatsu (large industrial conglomerates) for exploiting workers and fostering close ties with the government, which he believed compromised the well-being of the Japanese people for the benefit of the Zaibatsu. A blend of Buddhism, Lassallism, Marxism, and Platonism informed his opposition to capitalism, fueling his desire for Japan to be governed by leaders committed to the people's welfare rather than private profit. An intriguing aspect of Kita’s ideology is his frequent use of the term "social democracy," referring to the version advocated by Ferdinand Lassalle. George Wilson elaborates on the impact of Lassalle and Marx on Kita in this context:

“On Sado as elsewhere, the turn of the century brought a wave of fresh ideas. Socialism inherited the mantle of protest once worn by minken thinkers. Young socialists leaned toward the romantic, more influenced by the example of the effervescent Ferdinand Lassalle than by Karl Marx…”

— George Wilson, Radical Nationalist In Japan: Kita Ikki 1883-1937

However, modern liberals and certain critics have viewed this as an admission of “social-fascism.” Despite his admiration for Marx, Kita disagreed with him on aspects such as his perceived lack of spirituality. Still, in other areas, like Marx's economic analysis, Ikki Kita was among the first to praise him.

"Although Kita disagreed with Marx on some key points (for example, he vehemently rejected Marx’s theory of prices) and emphasized his own independent interpretation of socialism, he was highly influenced by Marxist ideas. Beginning from the first lines of Kokutairon, he declares himself ready to defend ‘scientific socialism’ against its critics, and, in all of his subsequent writings, he praises Marx for his profound understanding of historical, economical and social development. He even goes so far as to assert that the Marxist idea that ‘capital is an accumulation of plunder’ is an ‘unchanging truth equal to the law of gravitation’”

— Danny Orbach, A Japanese Prophet: Eschatology and Epistemology In The Thought of Kita Ikki

In his political agenda, a coup d'état was deemed necessary to implement a state of emergency regime under the direct leadership of a strong figure. Due to the Emperor's esteemed position within Japanese society, Kita viewed the sovereign as the perfect individual to suspend the Constitution, establish a council initiated by the Emperor, and fundamentally restructure the Cabinet and the Diet, with its members being elected by the populace and free from any "harmful influence." This would fulfill the true essence of the Meiji Restoration. The newly proposed "National Reorganization Diet" would revise the Constitution according to the Emperor's draft, impose limits on personal wealth, private property, and corporate assets, and create national entities directly managed by the Government, such as the Japanese Government Railways. Land reform would transfer all urban land to municipal ownership, mirroring significant reforms later implemented by Mao Zedong in China.

“Limitation on private property: No Japanese family shall possess property in excess of one million yen. A similar limitation shall apply to Japanese citizens holding property overseas. No one shall be permitted to make a gift of property to those related by blood or to others, or to transfer his property by other means with the intent of circumventing this limitation.”

“Lands to be owned by the state: Large forests, virgin lands which require large capital investment, and lands which can best be cultivated in large lots shall be owned and operated by the state.”

— Kita Ikki, An Outline Plan For The Reorganization of Japan

The new state would abolish the kazoku peerage system, the House of Peers, and all but fundamental taxes, ensuring male suffrage, freedom, property rights, education rights, labor rights, and human rights — all of these concepts borrowed from his readings on Lassalle. While maintaining the Emperor as the people's representative, privileged elites would be displaced, and the military would be empowered to strengthen Japan and enable it to liberate Asia from Western imperialism.

“Abolition of the peerage system: By abolishing the peerage system, we shall be able to remove the feudal aristocracy which constitutes a barrier between the Emperor and the people. In this way the spirit of the Meiji Restoration shall be proclaimed.”

— Kita Ikki, An Outline Plan For The Reorganization of Japan

Some scholars have dishonestly mistranslated his work and overly focused on Darwinism in his ideology, attempting to link it to figures like Hitler. However, Kita’s Darwinism was influenced by Marx, who was himself influenced by Darwin, making Kita more akin to the Darwinism seen in the Wobblies than that of Nazi Germany. This makes his stance comparable to that of Gramsci, Du Bois, Mao, or Sukarno, who disagreed with Marx but still saw him as an inspiration. Additionally, even the scholars who ascribed Darwinism to Kita, such as Nicholas Howard, have done so in their own words because they could not find the word for political Realism, the theory that focuses on the competitive and conflictual nature of politics and how power and security are the main issues in international relations.

Regarding Kita’s geopolitical outlook, Kita also envisioned Japan taking a leadership role in Asia and opposing Western imperialism by forming a "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere." Japanese militarists later co-opted this concept in the 1930s and 1940s to justify their expansion throughout Asia. Kita’s original vision for this "sphere" was a mutual alliance of Asian countries unified under Japanese leadership to resist Western influence collectively. While he perceived Japan as a liberator of Asia, he did not advocate for the exploitation or oppression of other Asian nations, as communist sources have tried to portray him as believing.

Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere poster, 1940s

The Greater East Asian Conference of 1943

“….[I]f someone calls the General Principles of the Reorganization of Japan a social revolutionary theory it would not be wrong…. In the past, the waves of ideas from Europe and America washed over Japan, but to deny that the wave of Japanese civilization will wash over America is really unscientific. The civilizations of Egypt and Babylon were followed by the Greek civilization, which in turn was replaced by Roman civilization. After the Roman civilization came that of individual nation-states…. A narrow-minded theory from Indian civilization became the basis of Western religious philosophy, but all traces of this in India itself were wiped out and its passage in China left only the bare bones. Only in a tiny island in the Eastern Sea was it closely treasured as a Great Way. Here it became Japanized, and later modernized, and now universalized and, after the coming of the Second World War, its revival will brighten the whole world. The renaissance of olden times will be nothing in comparison. The Western-Eastern culture will be of Asian thought Japanized and universalized, which will enlighten the vulgar, so-called civilized peoples.

The universe moves in a proper way, countries advance and decline. Just as for a few hundred years the countries of Europe did not allow people like Genghis Khan of the Mongol people to rule them, now how many years will the Anglo-Saxon tribe trample the world? History progresses. There are steps to advance. Historical progress in the East and West has gone through a 'warring states' (sengoku) period and after that followed what can be called the collective unification of feudal states, and so on up to the present international 'warring states' period and now the next stage is reached when world peace is made possible because a very powerful nation appears which will reign over the small and the big nations of the world, and establish a feudal peace (hokenteki heiwa). The various theories of world peace that seek to do away with national frontiers, based on the establishment of their ideals, ignore the conditions that make this possible, namely the realization of the great scientific inventions and the spiritual surge. The reality of ideals in all parts of the world is that there is always only one Toyotomi, Tokugawa, or one sacred emperor.

The Japanese people should consider that the older meaning of sovereignty, the supreme right, above the right to control, will be revived internationally and that the Supreme State, which controls various states, will be realized. The Land of the Gods is narrated in myths…. That the star flag of America presided over the meeting at the Versailles palace implicitly reveals that it was a dark night for the world. The Japanese rising sun flag, after defeating England, making India independent, and China self-reliant, will shed the light of Heaven on all the people of the world. The coming again of Christ, prophesied all over the world, is actually the Japanese people's scripture and sword in the shape of Mohammed. The Japanese people should face the historically unprecedented national difficulties that are coming by reforming the political and economic organizations based on the Fundamental Principles for the Reorganization of Japan. Japan, as the Greece of Asian civilization, destroyed a strong Russia, as Persia was in the sea battle of Salamis. It will only be then that the real awakening of the 700 million people of China and India begins. On the road to Heaven, there is no peace without war.”

— Kita Ikki, An Outline Plan For The Reorganization of Japan

Kita asserted Japan's entitlement as an "international proletariat" to take control of Siberia in the Far East and Australia, suggesting that the inhabitants of these regions should be afforded the same rights as Japanese citizens. He argued that Japan's domestic social issues could not be resolved without addressing global distribution challenges. This concept was known as the Shōwa Restoration. Kita perceived the world as divided into two classes: bourgeois and proletarian nations. He considered Japan a proletarian nation, lacking extensive territory (a large colonial empire) and financial resources (overseas investments). In contrast, he saw Russia as a major landowner with more than its fair share of global territory, while Britain was viewed as a rentier and financier. This perspective was very similar to the Italian proto-fascist Enrico Corradini.

“As a result of its own development, the state shall also have the right to start a war against those nations who occupy large colonies illegally and ignore the heavenly way of the co-existence of all humanity. (As a matter of real concern today, the state shall have the right to start a war against those nations which occupy Australia and Far Eastern Siberia for the purpose of acquiring them.)”

“The nation has the right to initiate a war, not just for self-defence but also for the other nations and races who are suppressed by an unprincipled power.”

— Kita Ikki, An Outline Plan For The Reorganization of Japan

Since the world was unfair and irrational according to Kita’s realist perspective, Kita argued that fighting for Japan's positive development was not selfish but a biological necessity and a revolutionary act for international justice. This sense of international justice and necessity led Kita to sympathize with Germany's challenge to the "international landowners and plutocracy" during WWI. Although Germany failed, Kita predicted that Japan would soon challenge these injustices and, after victory, become the "Germany of the East," acquiring Australia, Eastern Siberia, Pacific islands, Manchuria, and Mongolia. These territorial gains would ensure Japan's survival as a nation-state and secure China's territorial integrity and India's independence. However, Kita saw Asia's liberation as the first step toward a grander mission.

”The authority of the European theory of revolution is based on such a shallow and superficial philosophy so that when it is necessary to comprehend this philosophy of the 'gospel of the sword' then the noble Greece of Asian civilization itself must take the initiative for the reorganization of the nation, and waving the flag for an Asian alliance and a world alliance, spread the teachings of the Way of Heaven to the Four Seas that all people are children of the Buddha.”

— Kita Ikki, An Outline Plan For The Reorganization of Japan

Japan aspired to lead a global federation by propagating Buddhism's sacred principles worldwide. Kita believed that the international class struggle against landowners and the plutocracy was the key driving force in history. In its historical context, Kita's political vision sought to establish a socialist state using a fascist-oriented approach known as "socialism from above" to unify and strengthen Japanese society. Japan's international missions focused on securing India's independence and safeguarding the Republic of China, preventing it from being divided like Africa, in the spirit of Asian unity. Another objective of his plan was to create a vast empire that included Korea, Taiwan, Sakhalin, Manchuria, the Russian Far East, and Australia. This vision also entailed the ultimate rejection of the Western style of democracy, viewing it as foreign to Asian consciousness.

“There is absolutely no scientific basis for the thinking that a 'democracy', that is, a state system in which the representatives of the people are selected by an electoral system is better than a system where the state is represented by a single person. The nation differs according to the spirit of the peoples of each nation and the history of the formation of the nation. One cannot say that China, which has had a republican government for eight years, is more rational than Belgium where one person represents the nation. The American idea of 'democracy' is based on the idea of a society formed through the free will of individuals who enter into a free contract and the extremely crude ideas of the time that individuals broke away from the original countries of Europe and formed village communities and these became nations. The theory of the divine right of voters was a feeble philosophy, merely the obverse of the divine right of kings. This did not happen with the establishment of Japan, and neither was there a period when such a feeble philosophy was dominant. A system where the head of the state has to manipulate views by selling his name, refining his mannerisms like a low-class actor to fight elections, is for the Japanese race who have been brought up to believe that silence is golden and modesty a virtue, invitation enough to remain a mute spectator to this strange custom….”

— Kita Ikki, An Outline Plan For The Reorganization of Japan

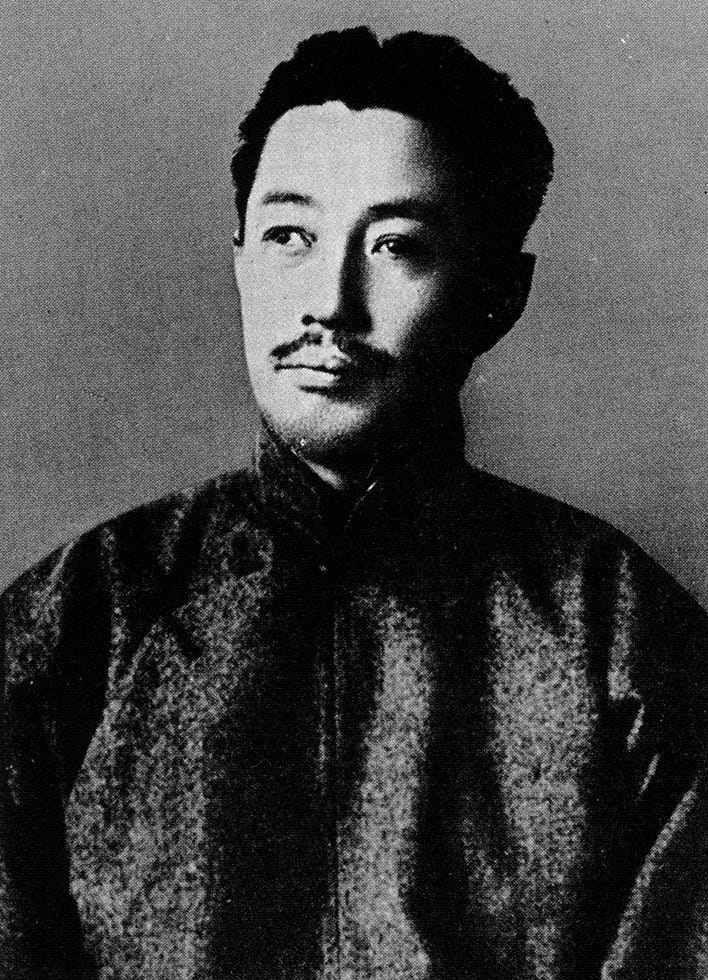

A photo of Ikki Kita

Kita proposed that the Empire of Japan adopt Esperanto in 1919 for his united world. He envisioned that 100 years after its adoption, Esperanto would be the sole language spoken in Japan and its vast conquered territories, with Japanese becoming akin to Sanskrit or Latin within the Empire. He believed that the Japanese writing system was too complex to impose on others, that romanization would be ineffective, and that English, taught in Japanese schools at the time, was not mastered by the Japanese. Kita argued that English was detrimental to Japanese minds, similar to how opium affected the Chinese and that it had not yet destroyed the Japanese because the German language had more influence. Still, He called for English to be excluded from Japan to prevent Japan from being anglicized. Kita was inspired by Chinese anarchists he befriended, who advocated substituting Chinese with Esperanto in the early twentieth century.

One of the most significant aspects of Kita's thought is the widespread influence of his Buddhism. Unlike the Shōwa Shintoists of his era, who were generally opposed to socialism, Kita embraced Nichiren Buddhism, a form of Mahayana Buddhism, or "Great Vehicle" Buddhism, that heavily encouraged political action and organization for the great coming war that Nicherene Foretold. This made Kita more open to socialism and diverse viewpoints than the Shintoists. Kita's Buddhism differed from Theravada Buddhism, or "Elder Buddhism," in that it focused on bodhisattvas and communal assistance in achieving nirvana. This form of Buddhism aligns well with socialism due to its communal aspects. However, exceptions exist, such as the Burmese Socialists under Ne Win and the Vajrayana Socialists under the Dalai Lama.

His Nicherene Buddhism also served a role in formulating his eschatology or how he viewed the cycle of history. Like Marx, he believed there was progress in history. Where he differed was with his Buddhist interpretation of cyclical history. Kita thought that the social democracy that he would implement would serve as the best staging ground for people to achieve nirvana and that the maintenance of this state would produce the most bodhisattvas to bring people close to nirvana. This thinking of mixing Buddhism and Marxism mirrored pure land Buddhism in a way that echoes the beliefs of a former fellow agrarian socialist warrior monk community in Japan called the Ikko Ikki.

From Nichiren to Ikki Kita, liberate ourselves from the west

In On The Kokutai and Pure Socialism, Kita also challenged the Shintoist perspective of nationalists like Hozumi Yatsuka, who viewed Japan as an ethnically homogeneous "family state" descended through the Imperial line from the goddess Amaterasu Omikami. Kita highlighted the historical presence of non-Japanese people in Japan and argued that, alongside the incorporation of Chinese, Koreans, and Russians as Japanese citizens during the Meiji period, anyone should be able to naturalize as a citizen of the empire, regardless of race, with the same rights and obligations as ethnic Japanese. He believed that the Japanese empire could not extend into non-Japanese regions without either granting them equal rights or excluding them from the empire. Concurrently, he held that Japan should preserve a distinctly Japanese identity to serve as the Bodhisattvas of the world. His views were akin to those of Italo Balbo and Gentile regarding immigration and assimilation policies.

Influence on Japanese Society and The Young Officers Movement

Although Kita's ideas did not gain widespread popularity, they resonated with younger, disillusioned Japanese military officers who viewed themselves as guardians of the emperor and Japan's future. This group became known as the "Young Officers," a coalition of right and left elements committed to purifying Japan. Particularly active in the 1930s, they advocated radical actions to remove corrupt leaders and realize Kita's vision of a restored, powerful Japan. They believed that only a revolutionary movement led by the military could save Japan from its societal and economic problems and maintain its autonomy against Western powers.

One of the factions within this coalition of young officers was the Sakurakai, or the Cherry Blossom Society, a nationalist secret society formed by young officers in the Imperial Japanese Army in September 1930. They aimed to reorganize the state along totalitarian militarist lines, potentially through a military coup d'état. The society pursued a Shōwa Restoration, intending to restore Emperor Shōwa to his rightful position, free from party politics and corrupt bureaucrats, under a new military dictatorship. They also supported State Socialism, as envisioned by Ikki.

Led by Lieutenant Colonel Kingoro Hashimoto, head of the Russian section of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff, and Captain Isamu Chō, with backing from Sadao Araki, the Sakurakai began with around ten active-duty field-grade officers from the Army General Staff. It eventually expanded to include regimental-grade and company-grade officers, growing to over 50 members by February 1931, and possibly several hundred by October 1931. A prominent leader was Kuniaki Koiso, a future Prime Minister of Japan. The Sakurakai held meetings in a dojo led by Morihei Ueshiba, the founder of Aikido, at the Oomoto religion headquarters in Ayabe.

In 1931, during the March Incident and the Imperial Colors Incident, the Sakurakai, along with civilian nationalist elements, attempted to overthrow the government. After the leadership's arrest following the Imperial Colors Incident, the Sakurakai disbanded, with many former members joining the Toseiha faction within the Army. The Young Officers' admiration for Kita's ideas led to several coup attempts throughout the 1930s, the most notable being the failed February 26 Incident of 1936. During this event, a group of young military officers attempted to seize the Japanese government and assassinate key political figures they viewed as obstacles to national reform. Although suppressed, the coup highlighted the extent of Kita's influence within military circles and the radicalization of some Japanese society factions.

The Kōdōha, or Imperial Way Faction, was founded by General Sadao Araki and his protégé, Jinzaburō Masaki. This radical faction aimed to establish a military government promoting totalitarian, militaristic, and aggressive expansionist ideas, gaining support mainly from young officers. The Kōdōha strongly backed the hokushin-ron ("Northern Expansion Doctrine"), advocating for a preemptive strike against the Soviet Union, believing Siberia was within Japan's sphere of interest. Although the Tōseiha also had proponents of Northern Expansion, they favored a more cautious defense expansion. Both factions struggled for military influence after the Manchurian Incident, but the Kōdōha remained dominant until Sadao Araki's resignation due to illness. He was succeeded by General Senjūrō Hayashi, who had Tōseiha sympathies. Consequently, after the February 26 Incident, the Kōdōha effectively dissolved, and the Tōseiha lost much of its purpose.

The Righteous Army was a group of young IJA officers who supported the radical Kodoha faction. These young officers believed Japan's problems stemmed from its deviation from the kokutai, a concept roughly signifying the relationship between the Emperor and the state. They felt that the "privileged classes" exploited the people, leading to widespread poverty in rural areas, and deceived the Emperor, thereby diminishing his power and weakening Japan. In their view, the solution was a "Shōwa Restoration" modeled after the Meiji Restoration of 70 years prior. Their beliefs were heavily influenced by contemporary nationalist thought, particularly the political philosophy of Ikki Kita. On February 26, 1936, they attempted a military coup aimed at purging the government and military leadership of their factional rivals and ideological opponents.

The February 26th Incident (26-28 February 1936), was an attempted coup d'état in the Empire of Japan, orchestrated by the young officers of the Righteous Army who supported the Kodoha. Their goal was to achieve the "Shōwa Restoration," purge their political opponents (notably the Tosei-ha), and restore direct rule under Emperor Showa (Hirohito). The envisioned "Shōwa Restoration" aimed to mirror the Meiji Restoration, with a small group of qualified individuals backing a strong Emperor. Although they succeeded in assassinating several leading officials and occupying the government center of Tokyo, they failed to assassinate Prime Minister Keisuke Okada, secure control of the Imperial Palace, or gain the Emperor's support. While their supporters in the army attempted to capitalize on their actions, internal divisions and widespread anger at the coup prevented any governmental change. Facing overwhelming opposition as the army moved against them, the rebels surrendered on February 29. This led to the suppression of the uprising, the decline of the Kodoha faction’s influence, and increased military influence over the government.

The Legacy and Execution of Kita Ikki

Kita had a profound and complex influence on Japanese nationalism and militarism. His intellectual work inspired radical reformists who supported the establishment of a strict military dictatorship and authoritarian governance. These ideas contributed to Japan's shift toward militarism during the turbulent 1930s and early 1940s, amidst widespread dissatisfaction with the ineffective Taisho democracy and geopolitical challenges, such as the end of the Anglo-Japanese treaty, which left Japan in isolation. Kita's vision of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, originally intended as an idealistic and cooperative endeavor, was altered to align with the Imperial Government's agenda. Figures like Konoe attempted to implement Kita's ideals through worker reforms, proposals for racial equality at the League of Nations, and efforts to secure pardons for the nationalist leaders involved in the 26 February incident, who had tried to assassinate his mentor Saionji. However, Konoe faced opposition from various factions within the Japanese government and external pressures, such as a vengeful United States and a scheming China. Ultimately, this led to Konoe, who favored diplomacy, relinquishing power to the more aggressive Hideki Tojo.

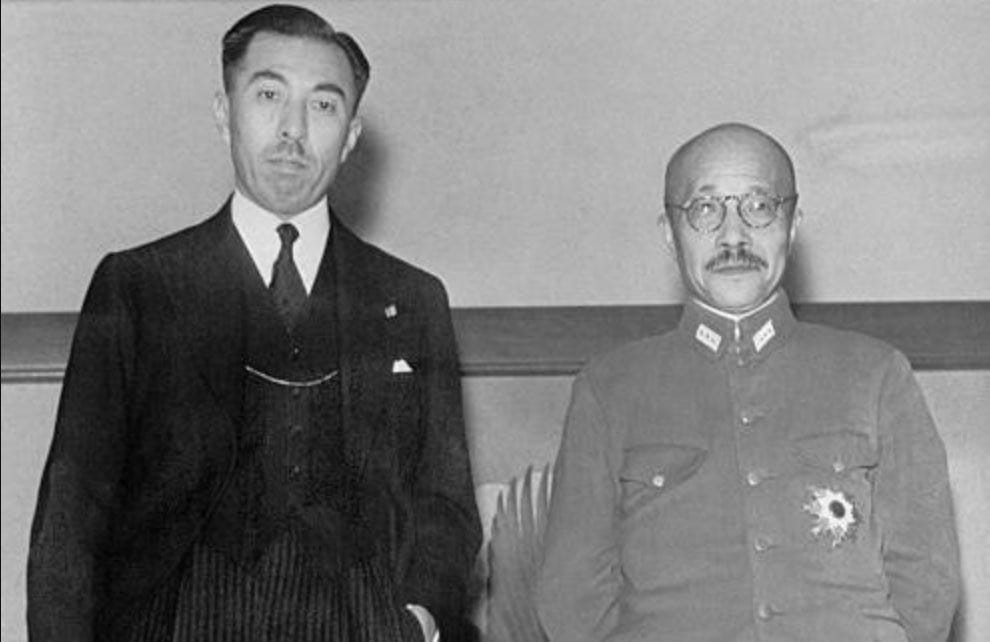

Hideki Tojo declaring war on America

In 1937, during the "February 26 Purge," Kita was arrested and executed by the Japanese government, which saw him as a threat to state security. Despite some of his ideas being partially adopted by the ruling authorities, Kita was seen as a dangerous ideologue, capable of inciting unrest and challenging the entrenched power of the elite. His execution did not end his influence; Kita's writings continued to resonate, becoming foundational texts for nationalist and militarist thinkers who envisioned Japan's salvation as a centralized, authoritarian socialist state.

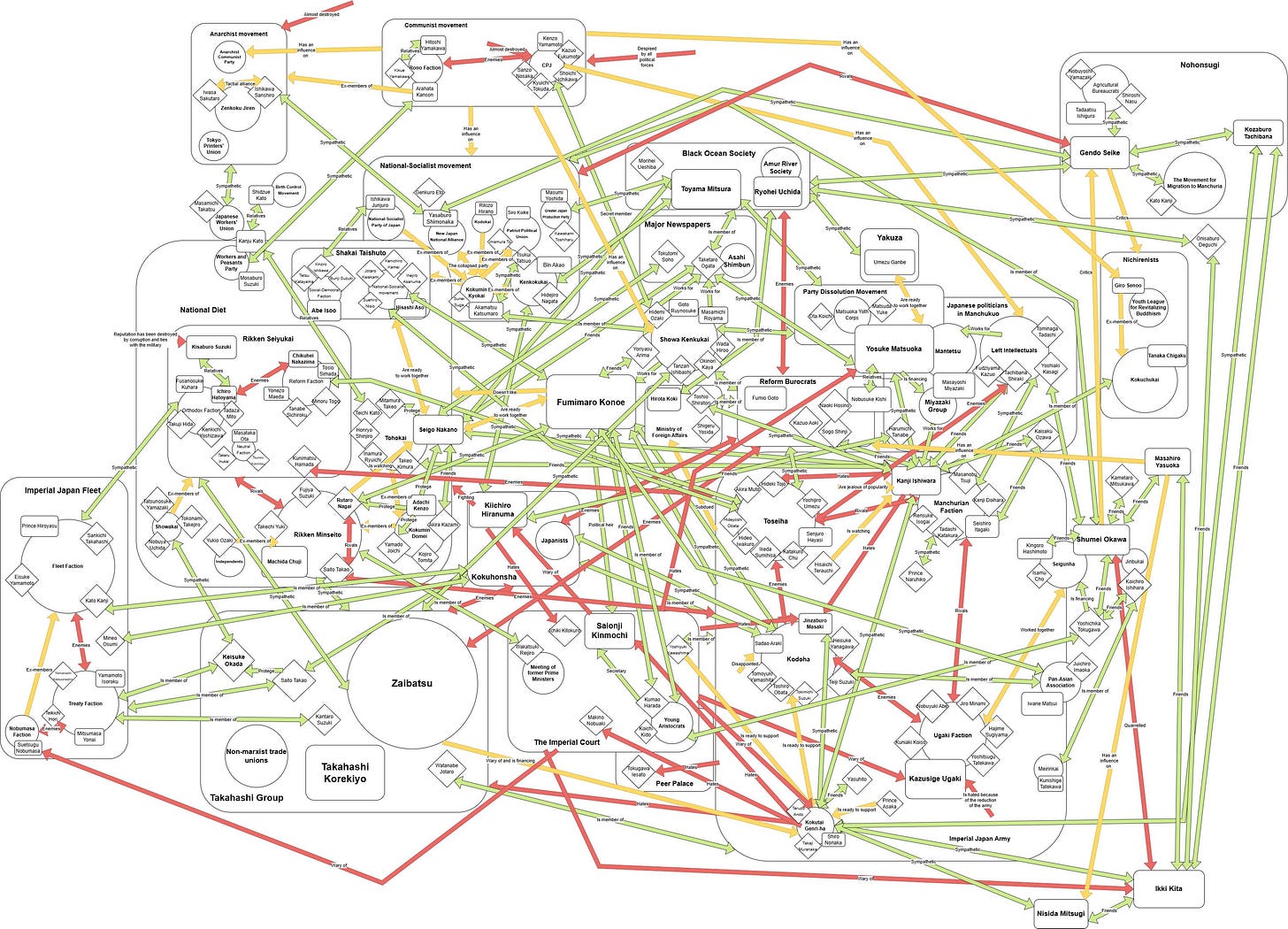

Everything in Imperial Japan is traced to Kita in the bottom right

Prince Fumimaro Konoe and Hideki Tojo

Konoe and Tojo’s vision aligned with Kita's focus on enhancing Japan's industrial capabilities, particularly under the Nikko branch, to boost defense supplies, essential industries, and export trade. The government planned to introduce legislation to support this expansion and ensure economic measures were in sync with military and financial needs. The New Order Movement, initiated by Konoe, aimed to move Japan away from the liberal capitalism of the West, inspired by the economic successes of Germany, Italy, and the Soviet Union during the Great Depression. This shift sought to challenge Western imperialism in Asia and required a long-term commitment and national unity to overcome the challenges ahead.

The policies that were desired, are grounded in the following principles:

The elimination of private property and the nationalization of the economy with military support, endorsing the socialist policies of Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and the Soviet Union under a single-party system.

To confront the imperialist powers of England, France, and America that dominate Asia.

Kita's ideological impact was unexpectedly profound, especially within North Korea's Juche ideology. This ideology reflects Kita's beliefs, including the Supreme Leader/Emperor concept, international cooperation against Western imperialism, anti-liberalism, anti-capitalism, state socialism, totalitarianism, and Songun. Despite its anti-Japanese rhetoric, these principles have allowed Kita's ideas to persist in North Korea. In South Korea, some liberal-left media have depicted Park Chung-hee's regime as anti-American, Pan-Asian fascist, and Chinilpa, with connections to Kita through his Japanese education and involvement in the February 6th incident. Inejiro Asanuma, a national socialist politician and leader of the Japan Socialist party, was deeply influenced by Kita and promoted an alliance with Mao and Sukarno, resonating with Kita’s Co-prosperity ideals.

Asanuma and Mao

Regarding the connections between Asanuma, Kita, and Konoe. Konoe, during his time at university, delved into socialism, notably translating Oscar Wilde's The Soul of Man Under Socialism into Japanese. His interest in socialism caught the attention of Sun Yat-Sen, who was influenced by Ikki Kita's ideas. After Japan's defeat in World War II, several of Konoe's former cabinet members, like Akira Kazami, joined the Japan Socialist party. Under the leadership of Asanuma, is often mistakenly associated with the Japanese Communist party, which was established by Kyuichi Tokuda and followed a path akin to Bernstein's reformist Marxism. Asanuma was profoundly influenced by Kita, supported Japan's wartime actions, and identified as a social democrat who favored class collaboration. Contrary to popular belief, he was not a communist sympathizer; instead, he criticized communists. Consequently, he was often derogatorily labeled a "fascist" and viewed as part of the right wing by the communists.

“The secretary-general of the recombined party is Inejiro Asanuma, a Right Winger.”

— Cecil H. Uyehara, The Social Democratic Movement

His associates pursued a form of national socialism distinct from Marxism, aimed at countering American liberalism. His strategic alignment with Mao during the Sino-Soviet split sought to forge an anti-Soviet and anti-American alliance. Bin Akao, who co-founded and initially led the Kenkokukai, became a notable nationalist figure in the 1920s. His nationalism was notably pro-American, pro-capitalist, and opposed to the Pacific War. Later, he established the Greater Japan Patriotic party in 1951, where he continued as its first president, often acting in favor of U.S. interests. Given this context, it's conceivable that Otoya Yamaguchi, who assassinated Asanuma, was influenced or directed by Akao's anti-socialist, pro-American sentiments, hinting that Yamaguchi might have been an asset manipulated by external forces. Yamaguchi, a pro-Anglo-American Japanese nationalist and protégé of Akao, assassinated Asanuma, which arguably suppressed true Japanese sovereignty movements and bolstered neo-conservative elements within various factions of Japanese nationalism.

Announcing the assassination of Japanese national socialist Asanuma

In modern Japan, the nationalist movement is largely subdued and disconnected from Kita's ideas, heavily influenced by Anglo-American perspectives — a scenario Kita would have strongly opposed. Alexander Dugin’s Fourth Political Theory aligns with some of Kita’s ideas when considered within the framework of current geopolitical alignments, as discussed by Kazuhiro Hayashida in What The Japanese Need to Understand The Fourth Political Theory. Kazuhiro emphasizes the importance of remembering historical ideas and figures to understand contemporary theories like Dugin's. Kazuhiro emphasizes Kanji Ishihara, a former Imperial Army soldier and fellow Nichiren Buddhist influenced by Kita, who was recognized for his strategic theories during the interwar period and his planning and execution of reclaiming Manchuria for the Qing Emperor, leading to Manchuria becoming an economic multicultural powerhouse for Japan’s ambitions through its collective farming practices and industrializations which raised living standards surpassing Japan in steel production. Coal mining, oil drilling, and agriculture were significant industries, ports and cities were modernized, trade and business boomed, and it was vastly industrialized compared to the Republic of China. This left Manchuria as the most industrialized area in all of China, leading to the Soviets using it as an operating base to allow Mao to eventually win the war. Although Ishihara's theories lost prominence after World War II, the author believes they still offer valuable insights. Ishihara's ideas, like Kita's, align well with Dugin's Fourth Political Theory.

The contemporary Chinese government maintains connections to Kita, as Deng Xiaoping's economic reforms were heavily influenced by Park Chung-hee and the Japanese economic model which inspired the Asian tiger economies. Chinese bureaucrat Wang Huning has also integrated many of Kita's ideas into China, steering the nation towards establishing a Pax Sinica through international initiatives like the Belt and Road project, reminiscent of the Black Dragon Society's efforts. Wang has expressed disdain for multiparty politics and has moved away from Marxism, advocating instead for a corporatist system.

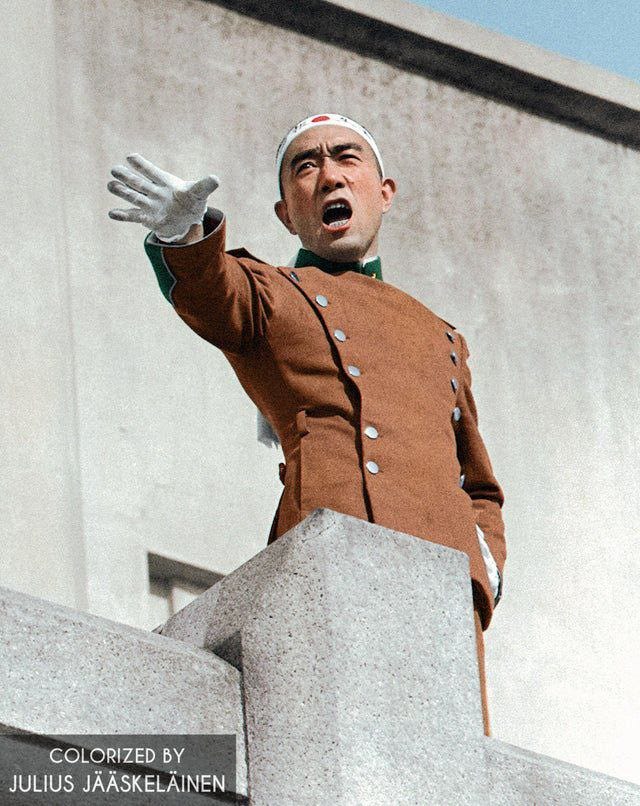

Yukio Mishima, was also greatly influenced by Kita, he believed his life should culminate in his own February 26th incident, aiming to restore Japanese sovereignty from Western influence or face an artistically significant death. To this end, he founded the Tatenokai, or Shield Society. Mishima cherished Japan's traditional culture and opposed Western materialism, globalism, and communism, fearing they would erode Japan's unique cultural identity and leave its people "rootless." On November 25, 1970, Mishima and four militia members entered a military base in central Tokyo, took the commandant hostage, and unsuccessfully attempted to rally the Japan Self-Defense Forces to overthrow Japan's 1947 Constitution. Following his speech, he shouted "Long live the Emperor!" before committing seppuku.

Yukio Mishima’s coup speech on November. 25, 1970

Kita remains a controversial figure in Japanese history. His radical ideology aimed to create a stronger and more equitable Japan by blending nationalism, socialism, and militarism to tackle issues such as economic disparity and Western imperialism. His ideas inspired many and posed a threat to established powers in the Soviet Union. The Western colonial powers and Japan itself launched a disinformation campaign to suppress his ideas and mischaracterize him. In truth, Kita sought to dismantle capitalism and saw himself as a totalitarian Buddhist using Japan as a vehicle for global enlightenment, echoing Fichte's vision for Germany. His quest for global Buddhist salvation positions him as a significant figure in the Japanese generic fascist/Third Position, alongside others like Akira Kazami to Seigō Nakano.

This Japanese piece, showing a steering wheel, it says “We steer toward peace”

“Japan, the land of the rising sun, the world of Tradition, the cult of ancestors, the cult of the elements - the Sun, the Moon, Water, mountains, streams, groves. The unique etiquette of the samurai. A warlike and heroic nation, mobilized for a common and total service to the highest solar ideal.

All this contrasted sharply with what we see in our homeland, in Germany and in Europe as a whole. Cosmopolitan cities, selfishness, capitalism, the market, venality, oblivion of higher ideals.

But at the same time, how close is Japan to the romantic soul of a German patriot, in love with German myths and legends, full of nostalgia for that golden feudal age, when Tradition flourished on the European continent—the age of Knights, Holy Empires and Magical Kings.”

— Karl Haushofer, Das Japanische Reich In Seiner Geographischen Entwicklung

“Japan is the only contemporary state that finds itself in the joyful condition of knowing nothing of the problem of the reconciliation between the national and racial idea and the religious idea.

This kind of view, which is still alive and well in Japan, reflects what every other traditional culture, of East and West, originally knew, but then lost.

It is in fact essential to acknowledge that, Japan still firmly defends values today that the West, in the contingencies of its history, has lost and can only hope to regain in future developments stemming from restorative revolutions.”

— Julius Evola, Traditionalist Confronts Fascism

Outstanding article, Zoltanus. Reading this, it got me thinking, do you view the Japanese Red Army in a similar light to that of their Red Army Fraction, in that they were a nationalistic organization using communism and sovietism for broad foreign support in a very Yockey-like way?