Within the debate about the historical placement of Hitler's National Socialism and its connection to fascism, a consistent theme arises. A range of voices—spanning from proponents of "Classical Fascism" to modern National Socialists, laypeople, and some academics—insist on distinguishing National Socialism as an ideology independent from fascism. Central to this debate is a contrast in focus: fascism is often described as prioritizing the state's supremacy, whereas Nazism is characterized by its intense focus on racial issues.

This can be observed in the following quotes:

“The Fascist conception of the state is all-embracing, outside of it no human or spiritual values can exist, much less have any real worth. Thus understood, Fascism is totalitarian, and the Fascist state-a synthesis and a unit of all values-interprets, develops and potentates the whole life of a people… It is not the nation that generates the state… Rather it is the state which creates the nation, conferring volition and, therefore, Real life on a people… In The Fascist conception, the state is an absolute before which individuals and groups are relative.”

—Benito Mussolini, The Doctrine of Fascism

“The State is only a means to an end. Its end and its purpose is to preserve and promote a community of human beings who are physically as well as spiritually kindred. Above all, it must preserve the existence of the race, thereby providing the indispensable condition for the free development of all the forces dormant in this race. A great part of these faculties will always have to be employed in the first place to maintain the physical existence of the race, and only a small portion will be free to work in the field of intellectual progress. But, as a matter of fact, the one is always the necessary counterpart of the other.

Those States which do not serve this purpose have no justification for their existence. They are monstrosities. The fact that they do exist is no more of a justification than the successful raids carried out by a band of pirates can be considered a justification of piracy.”

—Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf

Some people argue for a clear demarcation between fascism and National Socialism by citing Mussolini's documented criticism of Hitler and Nazism. This line of reasoning aims to underscore the perceived differences between the two doctrines, an interpretation that finds an echo among followers of the well-known YouTube channel TIKHistory, which similarly differentiates between Fascism from National Socialism. In the ongoing discourse about the links between Nazism and fascism, some contemporary adherents of National Socialism claim that fascism fails to fully grasp the concepts of race, the people, and the idea of a volksgemeinschaft, or ethnic community. On the other side, certain proponents of "Classical Fascism" might assert that Hitler was not truly a fascist. Then there are those who choose to ignore the racial component of these ideologies altogether. Nonetheless, these views tend to either miss or misrepresent the actual essence of both Nazism and Italian Fascism, possibly due to insufficient research or the spread of inaccurate information.

For a more precise comprehension of how Nazism and fascism are intertwined, an in-depth examination of the subject is essential, especially in light of the widespread misinformation that exists. Roger Griffin's influential book, Fascism, provides a useful analytical tool for constructing a persuasive case about this relationship.

It is essential to clarify four key terms:

Nazism or capital N-National Socialism: This means the German variation of fascism.

Capital F-Fascism: This means the Italian variation of Fascism

Generic fascism: This is “lowercase F” fascism (often referred to as generic fascism). Using this term is a broad way of characterizing Third Position movements by looking at what they have in common.

Non-Hitlerite “Lowercase N” national socialism. This is something that should be distinguished from both Hitler’s interpretation and generic fascism, as it’s something entirely different.

Utilizing Roger Griffin's framework, it becomes clear that when individuals draw a distinction between capital "F" Fascism and National Socialism, they are articulating a legitimate categorical distinction. They are recognizing the unique characteristics of Italian Fascism and German National Socialism as they manifested in their respective nations. Although this point might appear minor and not greatly advance the overall discourse, it is consistent with intuitive understanding and does not disrupt the more comprehensive conceptualization of the relationship between Nazism and fascism.

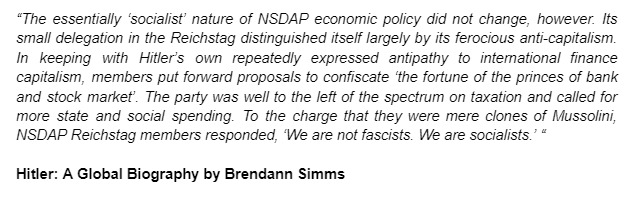

Reflecting on the specific character of National Socialism prompts a discussion on its proper classification. It's crucial to distinguish between Hitler's particular brand of National Socialism and the broader historical context of the national socialist movement in Germany. By making this distinction, it is defensible to differentiate the latter from fascism, especially when considering the contributions of individuals like Rudolf Jung and Otto Strasser. Members of Hitler's National Socialist German Workers' party (NSDAP) often eschewed the fascist label, preferring to align their beliefs with the original national socialist ideas advocated by figures such as Jung. This early strain of national socialism is distinct from the more generalized concept of fascism, and some NSDAP affiliates were deliberate in distancing themselves from the impression that they were simply imitators of Mussolini's ideology.

Before Hitler's ascent to power in Germany, "national socialism" was a term more commonly associated with a form of socialism that emphasized trade guilds or decentralized, council-based governance, sharing traits with Council Communism and carrying a pronounced nationalistic, or völkisch, flavor. This early version of national socialism didn't place a strong emphasis on racial ideology and its stance on anti-Semitism was not uniform. Key figures like Rudolf Jung, who was a socialist active in trade unionism, were instrumental in developing these concepts.

This initial version of national socialism can be regarded as an antecedent to Hitler's brand of National Socialism. Over time, Hitler adapted and transformed these early ideas, steering them towards a focus on a strong centralized state. It's important to acknowledge that Hitler's conception of the state and his interpretation of socialism were shaped by the ideas of the German philosopher Johann Fichte. Post-French Revolution, Fichte's thinking evolved, giving rise to his notion of "Ethical Socialism." The influence of Fichte's thought is traceable within both Italian Fascism and Hitler's National Socialism. Giovanni Gentile, the chief philosopher behind Italian Fascism, also drew from Fichte's philosophy, as reflected in various academic examinations of Gentile's work.

Examining Fichte's understanding of the role of the state, we find that he believed:

The essence of Fichte's political thought is often summarized by the dictum "Everything Inside the State, Nothing Outside the State, Nothing Against the State." Comparing this with Hitler's assertion that the state is a means to an end rather than an end in itself prompts a fascinating contrast. Yet, it's important to interpret Hitler's statement within the broader context of his ideology and to reconcile it with his other pronouncements for a full understanding.

Looking at the totality of Hitler's discourse reveals that he regarded the state as an indispensable mechanism for realizing his wider goals. Although he saw the state as instrumental, the ultimate goal was the creation of a society that epitomized the ideals of National Socialism. Hitler envisioned the state as a pivotal force in structuring and directing societal development, securing the well-being and advancement of the German nation. Therefore, while on the surface Hitler's remark might seem to conflict with Fichte's concept of a total state, it is essential to grasp Hitler's comprehensive perspective: the state as an essential apparatus for forging and upholding a societal framework that embodies National Socialist ideals.

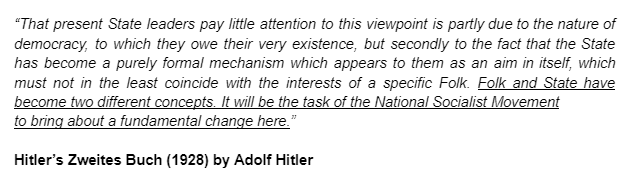

In his second book, Hitler would say the following:

Hitler viewed the relationship between the State and Race as inseparable, forming a cohesive entity. He was critical of Germany's past, lamenting the absence of a strong centralized state despite the existence of a German nation. Over time, he believed that these two elements, which had evolved separately, needed to be fused. In a 1923 interview with American Monthly, Hitler declared, "To us, Race and State are one." This assertion challenges the idea that Hitler considered the state to be trivial. By treating Race and State as synonymous, paralleling the way in which the State embodied the Nation in Italian Fascism, Hitler's ideology could be encapsulated by the maxim: "Everything inside Race, Nothing outside Race, Nothing against Race."

Hitler was chiefly concerned with the political order's use of the state apparatus and whether it could be harmful. This concern aligns with Mussolini's views, as both leaders were critical of liberal states. Therefore, the Italian emphasis on the primacy of the State over the nation can be understood as a result of historical context. The Italian Risorgimento, which aimed to unify Italy, only managed to do so on a superficial level. The Italian populace still lacked a cohesive culture, language, and identity—a unified Italy was more a romantic vision than a reality, alive in the works of poets and the dreams of a new Roman empire. Fascism, especially as interpreted by Giovanni Gentile, took on the task of advancing and finalizing the Risorgimento. By harnessing the power of the State, Fascism endeavored to forge and consolidate an Italian nation and race.

Hitler's embrace of the principle "Everything Inside the State" reflects a common thread running through both National Socialist and Italian Fascist ideologies, where the concepts of Race and State were of paramount importance. For Hitler and the National Socialists, as well as for the Italian Fascists, Race and State were deeply interconnected; the State was seen as instrumental in forging a unified national identity, or "Race." Nevertheless, the historical conditions of Germany and Italy were markedly different. In Italy's case, the creation of the State was imperative for the nation, or "Race," to coalesce, while the German people had a long-standing sense of national identity that predated a unified state structure. They were considered a Nation without a State, a reality recognized by Mussolini. This crucial historical nuance should inform our understanding of the two movements.

In Helmut Stellrecht's work, Faith and Action, the Nazi ideology is evident in its appropriation of Hegel's notion of "Race," which sought to blend the concept of "ethnos" (reflecting cultural and ethnic identity) with a living, organic State. This synthesis of race with the State was a cornerstone of Nazi philosophy, striving to create a society that was racially uniform and bound together under the guiding principles of the State.

“Race means to be able to think in a certain way.”

— Helmut Stellrecht, Faith and Action

Nazi intellectuals like Ernst Krieck and Friedrich Merkenschlager embraced a concept of race influenced by Hegel's The Philosophy of History. In this view, race is not defined solely by physical or material traits but also involves a particular way of thinking. The National Socialists believed that race entailed the ability to integrate seamlessly with the National Socialist State, thus embodying Hegel's definition of "Race." For them, race was as much a psychological phenomenon as a biological one. This perspective on race brought the Nazi viewpoint closer to that of Italian Fascism, which similarly highlighted the spiritual dimension of race. When considering Mussolini's reluctance to fully embrace Hitler, it's essential to recognize that his reservations were significantly colored by his anti-German prejudice rather than deep-seated ideological differences. Mussolini's assertions that Hitler was not a true fascist were often spurred by the dynamics of international politics or rooted in anti-German bias, occasionally both. These critiques were particularly vocal following the murder of Engelbert Dollfuss.

To understand Hitler's stance on Italian Fascism and his identification with fascism, one must delve into a range of resources, including his writings, oratory, and engagements with Mussolini. In his autobiographical manifesto, Mein Kampf, Hitler lauded Mussolini and his accomplishments in Italy. He regarded Mussolini as a formidable figure who had adeptly reformed Italy into a cohesive and orderly state. Hitler commended the organizational prowess of the Fascist party and their capacity to rally the populace.

We can see this in various other quotations:

The notion that Hitler's overtures toward Italy and Italian Fascism were purely motivated by a quest for power and international backing is contradicted by historical evidence. Records indicate that as early as 1928, Hitler saw Italy as a potential partner, reflecting a sincere respect for and influence from Mussolini's accomplishments. Hitler himself did not explicitly reject the fascist label. Although some of his associates, such as Joseph Goebbels—who initially had sympathies with the Strasser brothers' views—refuted the parallels between National Socialism and Italian Fascism during the 1920s, Hitler did not disassociate himself from being called a fascist.

Within the NSDAP, there were varying views regarding Italy and Italian Fascism. Some party members leveled criticism at Italy, deeming it too capitalist and contrary to National Socialism's goal of eradicating capitalism. For instance, Erich Koch criticized Italian Fascism as a capitalist form of imperialism. There were also allegations that Mussolini was a puppet for Jewish interests. These internal disagreements reflected the complex and sometimes conflicting ideologies within the party.

“Fascism can be defined as Jewish-Capitalist-Imperalism. German National Socialism, on the other hand is a movement for the social welfare of the people.”

— Jewish Telegraphic Agency, German Anti-semites Renounce “Fascisti” As Their Name; December 29, 1924.

Within the ranks of the Nazi party, figures like Otto Strasser, who initially dismissed Italian Fascism as too capitalist, eventually broke with Hitler over similar accusations of "capitalism." Otto Strasser went on to create his own brand of national socialism, positioning it as an anti-fascist ideology. On the other hand, personalities such as Goebbels, who may have started with divergent views, found their beliefs and positions increasingly converging with Hitler's over time as their association strengthened.

Italy was home to anti-Nazi Fascist figures like Berto Ricci, Italo Balbo, Stanis Ruinas, and Gabriele D'Annunzio, who resisted Italy's alliance with the Axis Powers, suggesting alternate alliances with Britain, France, or the USSR. Additionally, it's essential to clarify the misunderstandings regarding Nazi racial ideology and its stance on Nordicism. The Nazis moved away from Nordicism as their racial ideology evolved, adopting Dr. Walter Gross's framework, which did not espouse Nordicism's view of the inferiority of other Europeans. This is a point historian A. James Gregor has clarified in his work National Socialism and Race.

Fascism is not monolithic; it varies widely, adapting to each nation's particular economic, cultural, and historical context. Italian Fascism was a response to Italian issues, while Nazism was a reaction to German circumstances. Differences between the two were often the result of geopolitical dynamics and historical rivalries, similar to the ideological disputes between the USSR and Maoist China, despite both being communist. Both Mussolini and Hitler recognized the specificities of their respective ideologies. Perceptions of Mussolini's stance on Hitler's fascism or the views of Nazis critical of Mussolini should be viewed in light of anti-German sentiment or strategic positioning, with Mussolini wary of German ascendance. Conversely, Hitler was consistently vocal in his respect for Mussolini. It is also noteworthy that Mussolini referred to his ideology as "national socialism" prior to the foundation of the Italian Fascist party, illustrating the fluidity and interconnectedness of these political ideologies.

“It could be an anti-Marxist socialism, for instance; a national socialism. The millions of workers who will return to the furrows of their fields after having lived in the furrows of the trenches will realize the synthesis of the antithesis: class and nation.”

— Benito Mussolini, Trenchocracy December 15, 1917

Adopting the reasoning that Italian Fascism and National Socialism are distinct entities necessitates an examination of Mussolini's critiques and his deliberate dissociation from elements of Hitler's ideology. Consequently, it would be imprecise to consider Italian Fascism and National Socialism as equivalent solely on the basis of Mussolini's perspectives. Now, if Mussolini's views were the sole criterion for defining fascism, then, paradoxically, Stalin would have to be recognized as a fascist as well.

An intriguing aspect to consider is the endorsement and promotion by Mussolini's regime of Renzo Bertoni's book, Il trionfo del Fascismo nell'URSS (The Triumph of Fascism In The USSR), penned by an Italian Fascist. The book's title alone indicates that some Fascists perceived the USSR as a fascist state. This point is of particular interest as it undermines the stance of "Classical Fascists" who seek to dissociate themselves from Nazism by denouncing the Nazis as materialists. Yet, by acknowledging the USSR, with its Marxist-Leninist underpinnings, as fascist, they inadvertently associate themselves with a different strain of materialism. Furthermore, it's notable that in 1933, when Italy and Germany were at odds over Austria and war seemed a possibility, Mussolini referred to the Nazis as fascists, which was in stark contrast to his earlier anti-Nazi declarations.

Hitler's reluctance to distance himself from the label of fascism and his resistance to differentiating Nazism from fascism are significant. He forged a variant of Germanic fascism, which, while also stemming from the original German national socialism, was tailored to Germany's particular conditions and demands. It should be acknowledged that fascism can manifest racial aspects in different national contexts. Pointing out racism in other fascist states is not typically the concern of "Classical Fascists," as they consider the matters of other countries to be internal issues. Racism is not an all-encompassing feature of fascism; rather, fascism is an adaptive ideology that molds to the specificities of different nations, embracing distinct racial identities and myths within a unified national spirit. This is in line with the notion of Palingenetic Populist Ultranationalism, which seeks to cultivate a rebirth of the nation.

In examining the foundational beliefs of the Nazis and Italian Fascists, it is important to consider concepts such as myth, nationalism, imperialism, republicanism, the rule of philosopher-kings, totalitarianism, and corporatism, which are elaborated in The Doctrine of Fascism. Within this framework, Nazism can indeed be seen as a realization of Italian Fascist tenets. Griffin's interpretation of fascism highlights a rejuvenating form of nationalism that places the nation-state at the forefront. He draws comparisons between Mussolini, who showcased his Italian identity in his autobiography, and the Nazis, who placed a strong emphasis on German lineage. Through this lens, one can recognize the common threads in the ideological fabric of these two movements.

Nazi Playbook:

Build up the myth of the German nation

Build up the myth of German consciousness

Subordinate German people to nationalistic German consciousness

Direct and control with a Totalitarian State

Fascist Playbook:

Build up the myth of the Italian nation

Build up the myth of Italian consciousness

Subordinate Italian people to nationalistic Italian consciousness

Direct and control with a Totalitarian State

An examination of the Nazi regime's historical context and achievements shows that they implemented the ideas originally introduced by Italian Fascists with greater thoroughness. The Nazis adopted a more pure form of fascism, which allowed them to fully embody its tenets, leading to greater control and international impact during the war. Their significant role in shaping the global understanding of fascism supports the view that they were the foremost exemplars of the movement.

It's also worth considering the misconception that associates fascism exclusively with Giovanni Gentile's Actual Idealism. Alessandra Tarquini's work in The Anti-Gentilians During The Fascist Regime highlights the ideological variety within Italian Fascism, revealing internal disagreements that supported the regime's totalitarian bent. This diversity suggests that Italian Fascism wasn't purely based on Gentile's Actual Idealism. While Gentile was hegemonic, fascism encompasses a range of philosophic views, similar to the variances within modern communism. The Nazi party, for instance, had its own intellectual circle with a Hegelian slant, including figures like Julius Binder, Karl Larenz, Gerhard Dulckeit, and Carl Schmitt, while Hitler on the other hand was more influenced by Fichte, indicating that fascism is not monolithically linked to any single philosophical school of idealism.

Critics often focus on the distinct characteristics of fascist movements, contributing minimally to the broader discussion. It’s essential to understand that ideological expressions are shaped by specific historical, economic, and cultural conditions. Just as ideologies like Soviet Marxism-Leninism, Gonzalo Thought, or North Korea's Juche are built on unique interpretations, they all share a common ideological root. Critics frequently overlook this nuance, along with ignoring evidence such as Mussolini's racist views. Historians like Zeev Sternhell and Eugen Weber have pointed out the common lineage of Nazism and Italian Fascism with earlier movements such as Right Wing Jacobinism (Bonapartism) This shared lineage suggests that Nazism is indeed a variant of fascism, underpinning the assertion that while all Nazis are fascists, not all fascists are Nazis.

“Each nation will have "its" fascism; that is, a fascism adapted to the particular situation of that specific people: there is not and there will never be a fascism to be exported in standardized forms, but there is it is a complex of doctrines, methods, experiences, achievements, above all achievements, which little by little invest and penetrate all the states of the European community and which represent the "new" fact in the history of human civilization"

— Benito Mussolini, Il Popolo d'Italia, 1937

For further exploration on related topics, consider the following:

The Aryan Foundations of Fascism

Following the feedback on my article "What Is Fascism?", I will clarify the concept of the Aryan figure in the context of Fascist ideology. It's crucial to acknowledge that the ethnonationalist sentiment and völkische movement predating and permeating National Socialism weren't solely Adolf Hitler’s creations. These ideas and cultural tenets would likel…

Racism In Italian Fascism

Introduction The matter of race assumes a complex nature within the realm of Fascism. Its significance has infiltrated public discourse, as demonstrated by the recent statements of Paolo Di Canio, the esteemed Italian footballer, asserting that Fascism, as an ideology, does not inherently concern itself with race. Moreover, steadfast adherents of Nation…

What Is Fascism?

The question "What is Fascism?" has sparked a considerable amount of interest and debate among those seeking a clear understanding of the term. Unfortunately, attempts to provide a sincere answer have been complicated by misleading interpretations from figures such as Georgi Dimitrov and Jonah Goldberg, with Umberto Eco's explanation being particularly …

On The Different Interpretations of Fascism

Introduction Fascism is a complex and multifaceted ideology that has been interpreted in a various amount of ways, making it difficult to define with a singular, absolute definition. Scholars of all varieties have developed diverse interpretations, focusing on multitudes of different factors such as economic, social, cultural, intellectual, and psycholo…

How do you Fascists reconcile with the Holocaust? I'm not saying this as a challenge, I am genuinely curious.